SMALL BUSINESS RESEARCH PROGRAMS

Additional Actions Needed to Incorporate Best Practices for Addressing Foreign Risks

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact Candice N. Wright at WrightC@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

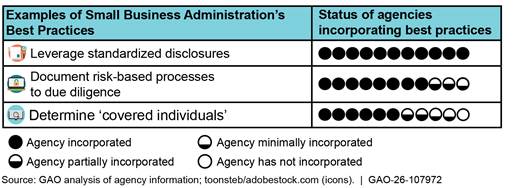

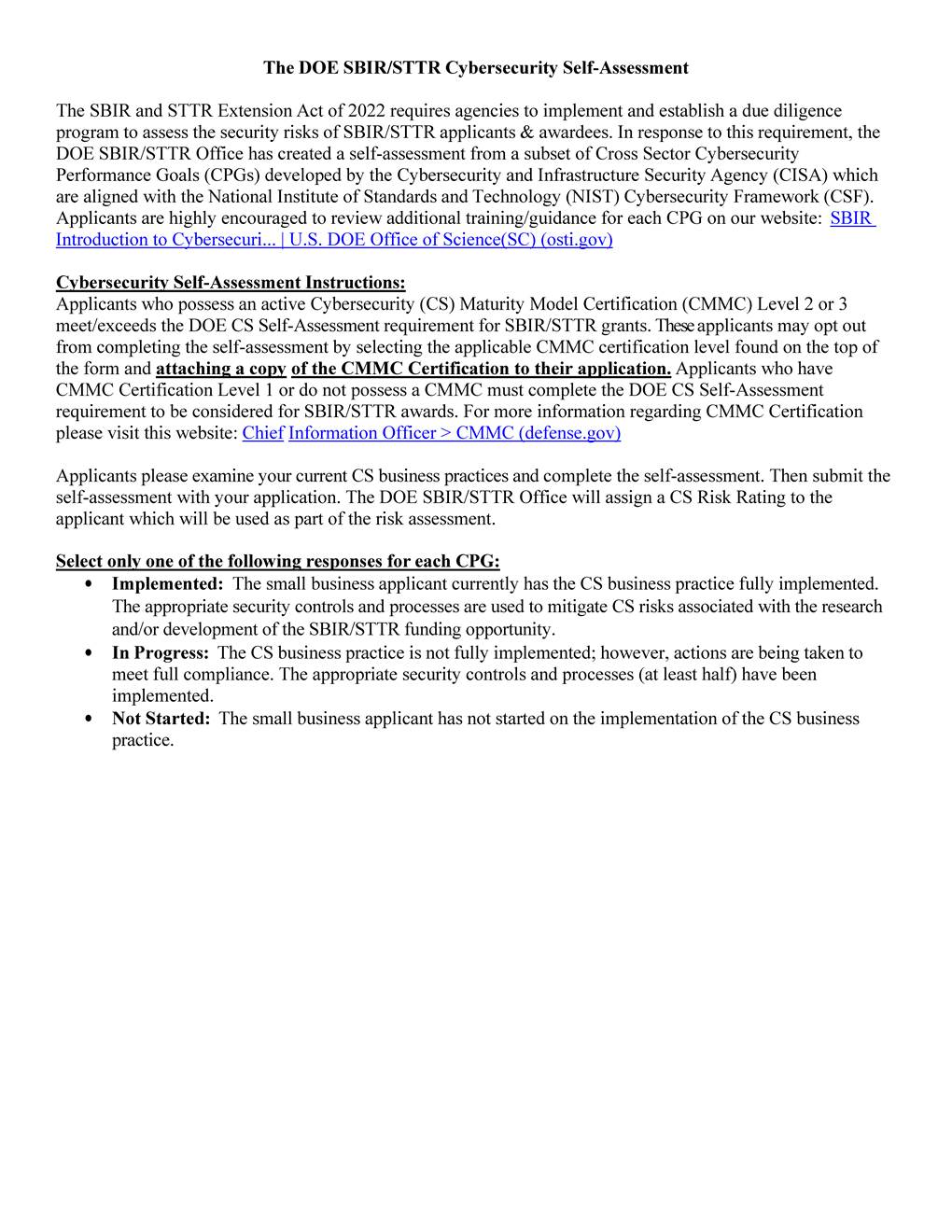

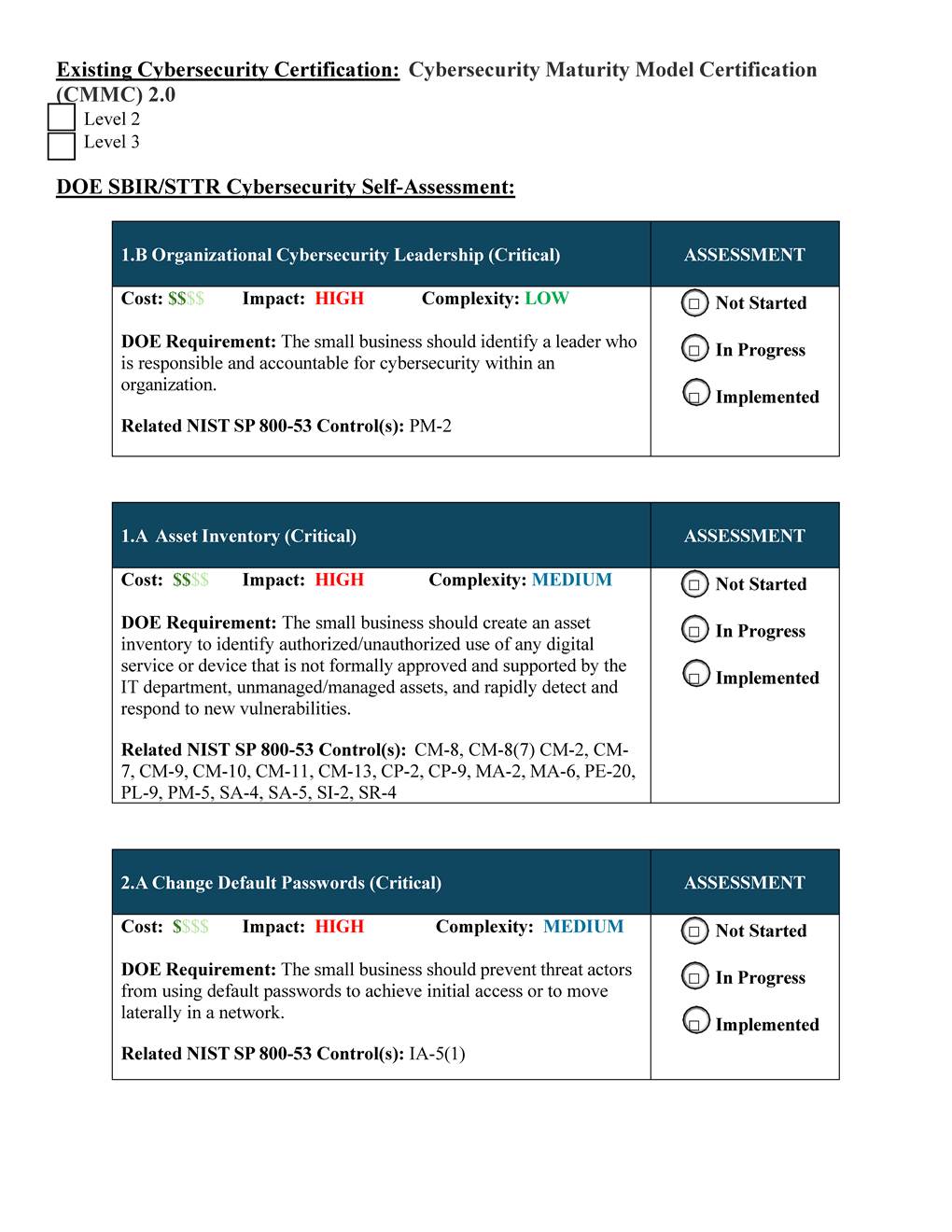

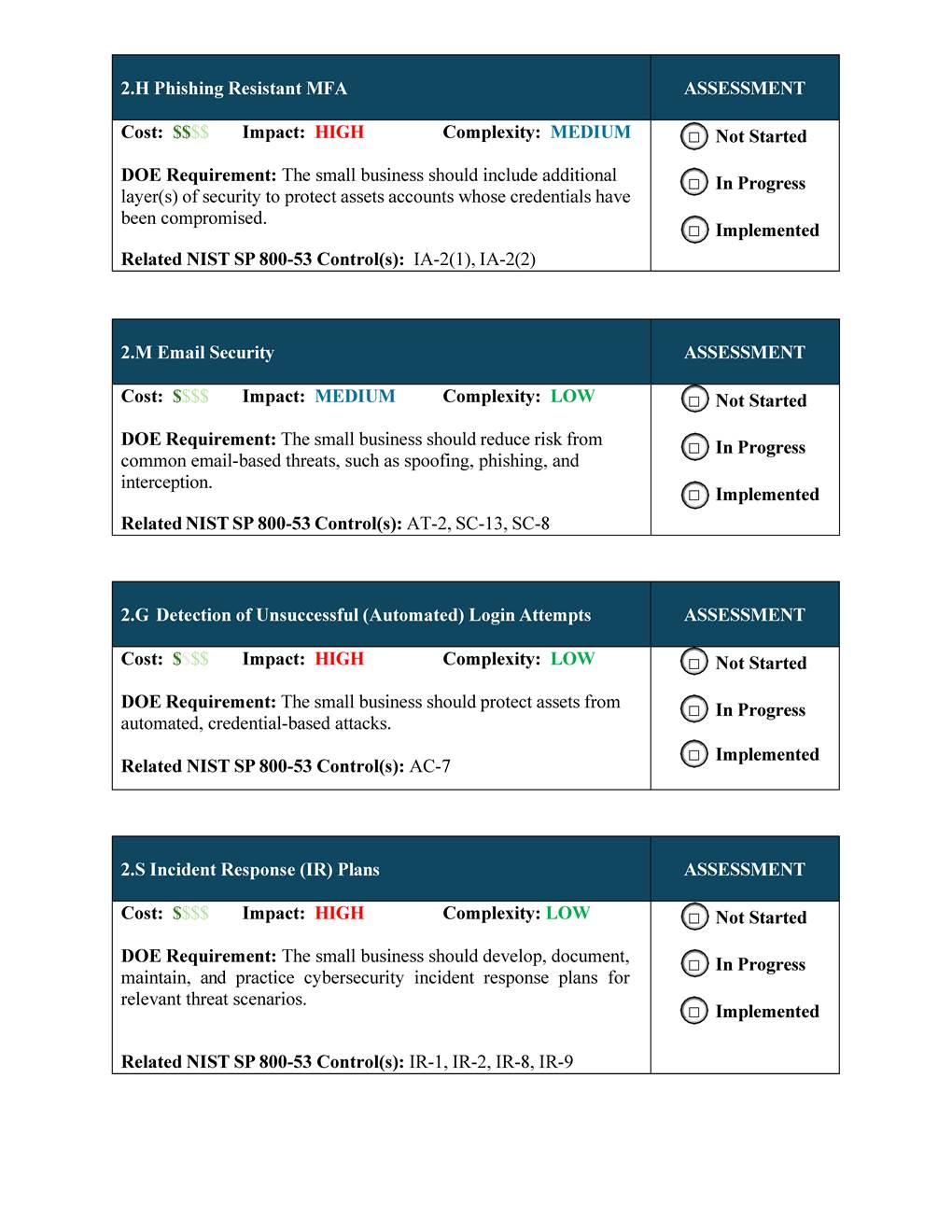

In March 2023, the Small Business Administration (SBA) established 12 best practices to help participating agencies manage risks posed by small business applicants in their Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs. GAO found that participating agencies and selected components have incorporated some best practices in their due diligence efforts, but gaps remain. For example, as of August 2025 all agencies had incorporated three of the 12 best practices, such as leveraging standardized foreign affiliation disclosures to capture consistent information. Most agencies incorporated additional practices, such as documenting a risk-based approach to their due diligence processes, and some incorporated practices such as determining “covered individuals” required to submit disclosures (see figure). The SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 (Extension Act) requires participating agencies to incorporate the applicable best practices in their due diligence programs to the extent practicable. Doing so may improve agencies’ ability to manage potential foreign risks.

The Extension Act also requires participating agencies to assess SBIR and STTR applicants’ cybersecurity practices. GAO found that nine of the 11 participating agencies and selected components did so using a variety of mechanisms, including business intelligence tools and self-assessment forms. However, two of the agencies GAO reviewed—the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)—are not assessing all applicants’ cybersecurity practices. NSF officials told GAO that its applicants are small and nascent companies with limited electronic assets or systems to protect. USDA officials stated they previously understood training applicants on cybersecurity would suffice as an assessment. Until NSF and USDA incorporate cybersecurity assessments into their due diligence programs, they are at an increased risk of making awards to applicants that are vulnerable to cyberattacks.

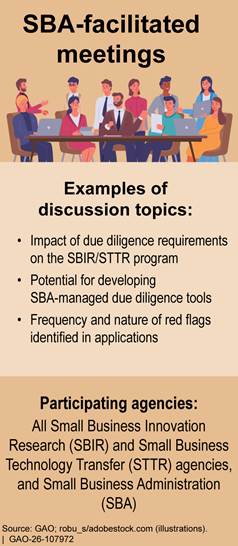

SBA conducts information sharing meetings for agencies to discuss due diligence efforts, but GAO found agencies have gaps in how they have incorporated SBA’s best practices to manage and reduce foreign risks. For example, GAO found some agencies are not incorporating certain best practices because, in part, they lack clarity on the intent of the practice or the best means to incorporate it. In August 2025, SBA officials acknowledged that based on the gaps and agency needs we identified in this report, additional opportunities may exist for SBA to engage with agencies on the challenges and impacts of incorporating the best practices and due diligence programs. The SBA-facilitated meetings could provide a discussion forum on agencies’ challenges in incorporating the best practices, potential for additional guidance, and possible revisions.

Why GAO Did This Study

The SBIR and STTR programs fund research and development (R&D) performed by U.S. small businesses. In fiscal year 2023, federal agencies issued more than 6,300 such awards in areas such as defense and environmental protection. However, Congress and U.S. intelligence agencies have expressed concerns about foreign adversaries exploiting potential vulnerabilities in these programs and in entrepreneurial small businesses.

The Extension Act requires the 11 participating agencies to implement due diligence programs to assess the security risks posed by small business applicants. It includes a provision for GAO to issue a series of reports on the implementation and best practices of agencies’ due diligence. This report is the third in this series and examines (1) agencies’ incorporation of the best practices, (2) their assessments of applicants’ cybersecurity practices, and (3) interagency mechanisms for sharing information on due diligence programs.

To determine the extent to which agencies have incorporated SBA’s best practices, GAO reviewed agencies’ policies and procedures for conducting due diligence and assessing applicants’ cybersecurity practices. GAO also interviewed SBA and SBIR and STTR program officials at the participating agencies and selected components on the best practices.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making a total of 26 recommendations: 25 to 10 agencies on incorporating SBA’s best practices on due diligence programs and one to SBA on leveraging its interagency meetings to discuss the practices and help agencies address them. The agencies agreed with the recommendations.

Abbreviations

DHS Department of Homeland Security

DOD Department of Defense

DOE Department of Energy

DOT Department of Transportation

EPA Environmental Protection Agency

FY fiscal year

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

NASA National Aeronautics and Space Administration

NIH National Institutes of Health

NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology

NOAA National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

NSF National Science Foundation

OCEA Air Force Office of Commercial and Economic Analysis

R&D research and development

SBA Small Business Administration

SBIR Small Business Innovation Research

STTR Small Business Technology Transfer

USDA U.S. Department of Agriculture

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 28, 2026

Congressional Committees

The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs were established by Congress to enable small businesses to undertake and obtain the benefits of research and development (R&D). The SBIR and STTR programs aim to support scientific excellence and technological innovation through investment of federal research funds in areas such as transportation, health, and energy, with the goal of building a strong national economy.[1] According to data from the Small Business Administration (SBA), which is responsible for overseeing the SBIR and STTR programs, in fiscal year (FY) 2023 the 11 agencies participating in these programs issued more than 6,300 awards valued at approximately $4.5 billion to over 3,000 small businesses. The participating agencies support small businesses through awards (i.e., contracts, grants, or cooperative agreements) and fund projects in areas such as defense, information technology, and environmental protection.

However, Congress has expressed concerns about foreign adversaries exploiting potential vulnerabilities in these programs. In February 2025, several House of Representatives committees jointly sent letters to each of the participating agencies requesting information about foreign risks to the program. Furthermore, in July 2024 U.S. intelligence agencies warned that emerging technology companies could be targeted by foreign actors seeking to obtain proprietary data, advance their nation’s economic and military capabilities, and threaten U.S. national security.

The SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 requires the 11 federal agencies participating in one or both of these programs to implement due diligence programs to assess the security risks posed by small business applicants.[2] These programs address risks in four areas: foreign ownership, employee affiliations, patent analysis, and cybersecurity practices. In March 2023, SBA issued a list of 12 best practices for agencies participating in SBIR and STTR to incorporate in their risk-based due diligence programs to address foreign risk. We previously reported that most agencies have identified some risks through their due diligence programs and have taken steps to further refine their approaches for conducting due diligence.[3] In 2024, we found that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) did not have documented processes for requesting analytical support and sharing information, including classified information, to support due diligence activities.[4] We recommended these agencies document agreed-upon procedures between SBIR and STTR program offices and counterintelligence offices for supporting due diligence reviews. The three agencies concurred with our recommendation and have told us they are working to implement their respective recommendations.

The Extension Act also includes provisions for GAO to issue a series of reports on the implementation and best practices of agencies’ due diligence programs to assess security risks presented by small businesses seeking a federally funded award. This report, the third in the series, examines (1) the extent to which agencies are incorporating SBA’s best practices for the SBIR and STTR due diligence programs; (2) the extent to which agencies assess the cybersecurity practices of small businesses seeking SBIR and STTR awards; and (3) the mechanisms that exist for agencies to share information on practices, risks, and challenges in their SBIR and STTR due diligence programs.

The scope includes SBA and the 11 participating agencies. For the five agencies with more than one component that issues awards—the Departments of Commerce, Defense (DOD), Energy (DOE), Health and Human Services (HHS), and Homeland Security (DHS)—we selected the component that issued the highest number of awards in FY 2023, which were the most complete data available at the time of our review. The selected components include: the Air Force in DOD; National Institutes of Health (NIH) in HHS; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in Commerce; Science and Technology Directorate in DHS; and Office of Science in DOE.[5]

For the six remaining agencies—the Departments of Agriculture (USDA), Education, and Transportation (DOT); Environmental Protection Agency (EPA); National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA); and National Science Foundation (NSF)—we reviewed the one component in each agency that issues all SBIR or STTR awards.

To address the objectives, we obtained and reviewed agency policies and documents; and interviewed relevant agency officials. For the first objective, we applied SBA’s 12 best practices for conducting due diligence to address foreign risks and federal internal controls to the 11 SBIR and STTR participating agencies or selected components we reviewed.[6] Based on our review of agency documents and interviews, we determined whether a specific SBA best practice was incorporated, partially incorporated, minimally incorporated, or not incorporated by the agency in its due diligence program as of August 2025.[7]

For the second objective, we reviewed processes and tools used by participating agencies to assess award applicants’ cybersecurity practices as required by the Extension Act. For the third objective, we collected documents including agendas from SBA-facilitated program manager and due diligence meetings and interviewed SBA officials on the best practices. We also interviewed SBIR and STTR program officials at the participating agencies and selected components to discuss mechanisms available for them to exchange information on their programs with other participating agencies. For more information on the objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2024 to January 2026 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of SBIR and STTR Programs

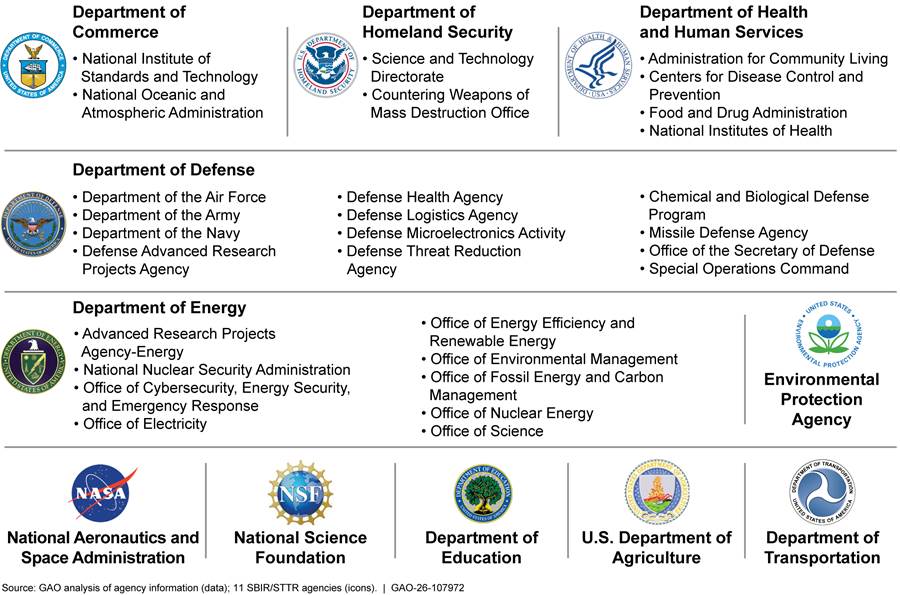

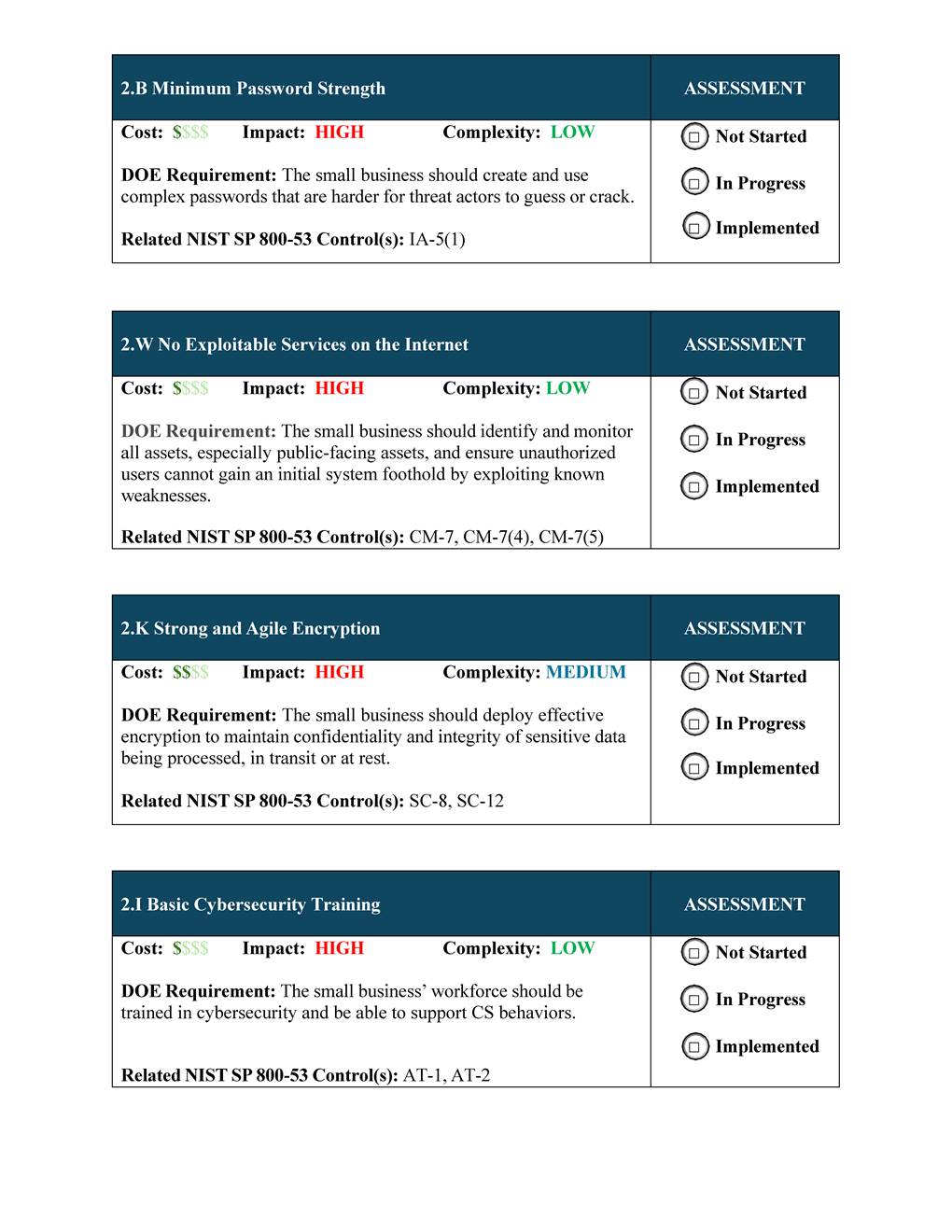

Federal agencies with an extramural research or R&D budget greater than $100 million are required to participate in the SBIR program, and agencies with R&D obligations of more than $1 billion are required to participate in the STTR program, pursuant to the Small Business Act.[8] These programs issue competitive awards to small businesses to support scientific excellence and technological innovation for economic purposes. These awards can come in the form of contracts, grants, or cooperative agreements. According to SBA, 11 federal agencies and their components participate in the SBIR and STTR programs (see fig. 1).[9]

Figure 1: Eleven Agencies Participating in the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs

Note: Six agencies currently participate in STTR: the Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Energy, and Health and Human Services; the National Aeronautics and Space Administration; and the National Science Foundation. In addition to the Department of Defense components listed, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Strategic Capabilities Office, and the Space Development Agency also participate in the SBIR and STTR programs. However, according to agency officials, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency and Strategic Capabilities Office issue solicitation topics through the Office of the Secretary of Defense, while the Space Development Agency issues solicitation topics through the Department of the Air Force.

SBA’s Best Practices in Due Diligence Activities

The Extension Act directed agencies that participate in the SBIR and STTR programs to use a risk-based approach as appropriate to assess security risks associated with small businesses seeking an award in four areas:

· Cybersecurity practices. Despite the increase in cybercrime awareness, many small businesses remain vulnerable due to a lack of resources and knowledge, according to SBA. Incorporating cybersecurity practices can help protect information related to federally funded research.[10]

· Patent analysis. SBIR and STTR awards are potentially subject to technology and intellectual property risks that may be identified through patent analysis. Agencies can use data from patent applications and issued patents to uncover potential relationships between entities or individuals and foreign actors.

· Employee affiliations. Employees who perform R&D using a SBIR or STTR award may be subject to exploitation attempts to obtain sensitive research information. Agencies are to assess potential risks of employee affiliations and financial obligations and ties with foreign countries. Agencies may focus particularly on those employees who can significantly influence the direction of the research, the acquisition of data, or the method and analysis of the research.

· Foreign ownership. Consistent with federal regulations and to be eligible for SBIR and STTR awards, businesses must meet specific eligibility requirements.[11] For example, a SBIR or STTR awardee must generally be at least 50 percent directly owned and controlled by U.S. citizens or permanent residents. Due diligence programs are to assess a small business’s financial ties and obligations to a foreign country, entity, or person.

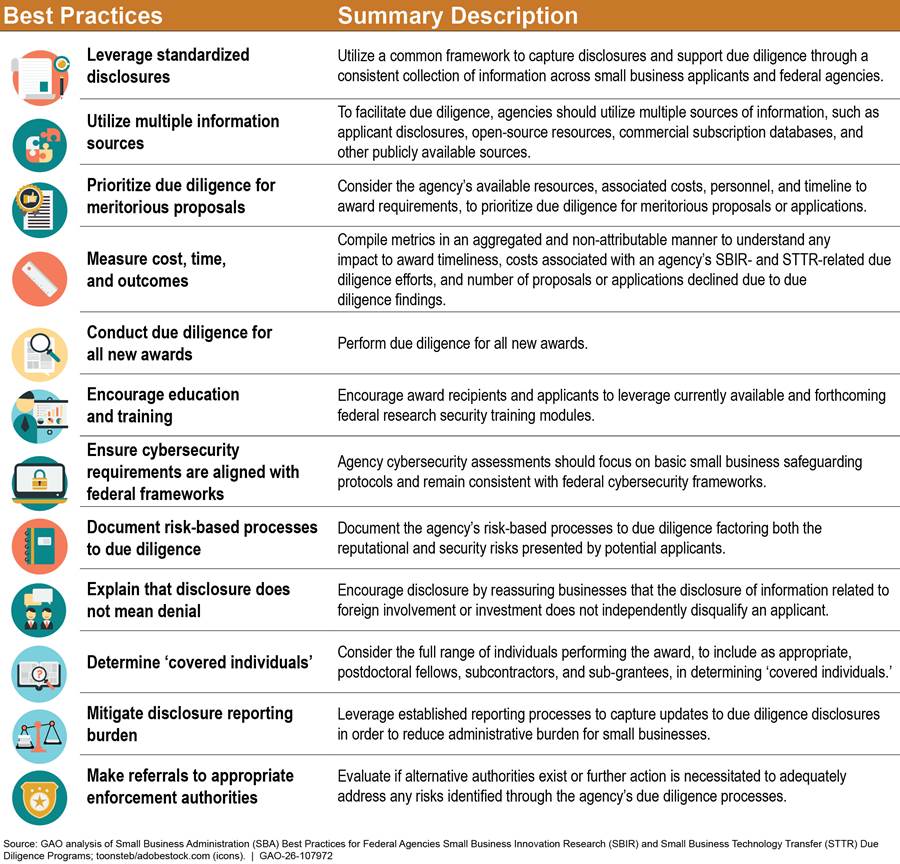

The Extension Act also requires SBA to disseminate due diligence best practices to SBIR and STTR participating agencies. These best practices were developed in collaboration with the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, and the 11 participating agencies. The Extension Act requires the agencies to incorporate the applicable best practices disseminated by SBA into their due diligence programs “to the extent practicable.” In March 2023, SBA issued a list of 12 best practices for SBIR and STTR participating agencies to incorporate. Figure 2 shows a summary of SBA’s best practices for the due diligence programs.

Figure 2: Summary of SBA Best Practices for Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Due Diligence Programs

Note: In general, the term “covered individual” means an individual who (1) contributes in a substantive, meaningful way to the scientific development or execution of a R&D project proposed to be carried out with a R&D award from a federal research agency; and (2) is designated as a covered individual by the federal research agency concerned.

We previously reported that SBA’s efforts to develop the best practices reflected selected practices we identified for effective collaboration, including defining a common outcome, bridging organizational cultures, and ensuring that relevant participants are included.[12] SBA also developed a set of standardized disclosure questions about foreign affiliations or relationships to foreign countries that SBIR and STTR applicants must answer to help participating agencies assess foreign influence.

Agencies Incorporated Some Best Practices, but Gaps Remain

As of August 2025, of the 12 best practices SBA established for agencies’ due diligence programs, all participating agencies and selected components we reviewed incorporated three practices: leveraging standardized disclosures, using multiple information sources to screen applicants, and prioritizing due diligence for meritorious proposals. Most incorporated additional practices such as measuring cost, time, and outcomes of their due diligence programs; conducting due diligence on all new awards; and encouraging education and training.[13] Some agencies have incorporated practices on explaining that disclosure does not mean denial and determining “covered individuals” but have not adopted others. A few agencies have taken some steps to mitigate the disclosure reporting burden and refer risks identified during due diligence to other authorities.

We reported in November 2023 that participating agency officials had stated (1) the best practices are helpful, cover different types of risk, and are sufficiently granular to use in developing their agencies’ due diligence programs and (2) the best practices are minimum standards that their agencies could build upon, based on their individual needs.[14] Figure 3 shows the status of participating agencies and selected components incorporating SBA’s best practices as of August 2025.

Figure 3: Status of Due Diligence Best Practices Incorporated by Participating Agencies and Selected Components, as of August 2025

All Agencies Have Incorporated Practices on Disclosures, Information Sources, and Proposal Prioritization

All participating agencies and selected components that we reviewed have incorporated three of the best practices: leveraging standardized disclosures, using multiple sources of information to screen applicants, and prioritizing due diligence for meritorious proposals.

|

Utilize a common framework to capture disclosures and support due diligence through a consistent collection of information across small business applicants and federal agencies. Source: GAO analysis of agency information; toonsteb/adobestock.com (icons). | GAO‑26‑107972 |

Leverage standardized disclosures. All participating agencies and selected components (Air Force, DHS, DOE, DOT, Education, EPA, NASA, NIH, NOAA, NSF, USDA) leverage the standardized form for disclosing foreign affiliations and foreign relationships that was published in the SBA SBIR and STTR Program Policy Directive in May 2023. Two agencies (Education, NSF) include additional questions specific to their agencies in the disclosure form. For example, Education asks applicants to provide more specific details on patents held, foreign funding, and affiliations of covered individuals.

The standardized disclosure form includes questions such as whether an applicant or a recipient party participates in any malign foreign talent recruitment program; whether there is a parent company, joint venture, or subsidiary of the applicant that is based in or receives funding from any foreign country of concern; or whether the applicant or recipient has any venture capital or institutional investment.[15] According to SBA, the form allows agencies to collect standardized information across all applicants and mitigates the burden on applicants seeking funding from multiple programs at different agencies.

|

To facilitate due diligence, agencies should utilize multiple sources of information, such as applicant disclosures, open-source resources, commercial subscription databases, and other publicly available sources. Source: GAO analysis of agency information; toonsteb/adobestock.com (icons). | GAO‑26‑107972 |

Utilize multiple information sources. All participating agencies and selected components (Air Force, DHS, DOE, DOT, Education, EPA, NASA, NIH, NOAA, NSF, USDA) use multiple sources of information—such as applicant disclosure forms, open-source information, or commercial databases—to screen applicants. For example, DHS uses various open-source data to verify information provided in the disclosure form. In another example, USDA uses information from government databases (e.g., databases to help prevent and detect improper payments and to search public patents) in addition to the disclosure form, to identify risks in patent analysis, employee affiliations, and foreign ownership. Some agencies, such as Air Force, DOE, and EPA, cite the use of classified sources or counterintelligence information in their due diligence plans.

|

Consider the agency’s available resources, associated costs, personnel, and timeline to award requirements, to prioritize due diligence for meritorious proposals or applications. Source: GAO analysis of agency information; toonsteb/adobestock.com (icons). | GAO‑26‑107972 |

Prioritize due diligence for meritorious proposals. All participating agencies (Air Force, DHS, DOE, DOT, Education, EPA, NASA, NIH, NOAA, NSF, USDA) prioritize due diligence for meritorious proposals. We found agencies incorporate this best practice in different ways. For example, NOAA requires all applicants to complete the standardized disclosure form but conducts due diligence only on applications that are deemed meritorious by subject matter experts. On the other hand, Air Force reviews the standardized disclosure forms for all proposals and then conducts additional due diligence for proposals that have passed a technical evaluation. In both cases, these agencies prioritize due diligence for meritorious proposals—applications that passed an initial round of review.

Most Agencies Have Incorporated Practices on Measuring Outcomes, Encouraging Training, and Other Practices

We also found that most of the participating agencies and selected components we reviewed incorporated practices on measuring cost, time, and outcomes; conducting due diligence for all new awards; encouraging education and training; and documenting risk-based processes to conduct due diligence.[16]

|

Compile metrics in an aggregated and non-attributable manner to understand any impact to award timeliness metrics, the direct costs of the agency’s SBIR- and STTR-related due diligence efforts and capture the aggregate number of proposals or applications that cannot proceed due to due diligence findings. Source: GAO analysis of agency information; toonsteb/adobestock.com (icons). | GAO‑26‑107972 |

Measure cost, time, and outcomes. Ten agencies (Air Force, DHS, DOE, DOT, Education, EPA, NASA, NIH, NOAA, USDA) have compiled metrics related to cost, time, and outcomes associated with due diligence.[17] For example, agencies must report annually to SBA and Congress on the costs of establishing their due diligence programs.[18] For FY 2024, agencies reported costs such as salaries and training for program staff and subscription fees for commercial databases. Agencies use various methods to track these three metrics, including dashboards, internal reports, and spreadsheets.

For example, Air Force uses a dashboard and spreadsheets to track direct costs, timeliness, and outcomes of awards. Air Force officials explained that because the due diligence process is supported by multiple teams and Air Force organizations, program staff track many metrics to understand where process improvements can be made.[19] Education uses a spreadsheet to ensure that award recipients are notified within 90 days of proposal submission.[20] In another example, to ensure awards are made in a timely manner, NIH alerts relevant stakeholders when an application’s foreign risk assessment has been pending for greater than 25 days . NIH also calculates the length of time for an application to receive a foreign risk clearance and shares this information with NIH program staff and leadership.

One agency (NSF) has partially incorporated this practice. NSF has established processes to track two of the three metrics (outcome and costs), but it has not established a metric to measure the impact of due diligence on the timeliness of awards. Officials stated that it would be very difficult to isolate the impact of the Extension Act’s requirements for due diligence activities from other factors that may affect award timeliness and that it would be challenging to implement such a process and consume valuable resources and staff time. We have previously reported that award timeliness in the SBIR and STTR programs is important to enable the businesses to begin work under the awards and avoid potential negative effects that delays in award funding may have on recipients’ business practices.[21]

The SBA best practice encourages agencies to compile metrics to understand the impact of due diligence activities on award timeliness. Federal internal controls also state that agencies should define objectives in measurable terms so that performance toward those objectives can be assessed.[22] Establishing metrics on the impact to award timeliness could help NSF determine necessary resources for the programs and provide indications of program effectiveness.

|

Perform due diligence for all new awards. Source: GAO analysis of agency information; toonsteb/adobestock.com (icons). | GAO‑26‑107972 |

Conduct due diligence for all new awards. Ten agencies (Air Force, DHS, DOE, DOT, Education, EPA, NASA, NIH, NOAA, USDA) have established processes to ensure that due diligence is performed on all new awards to address all four risk areas identified in the Extension Act—cybersecurity practices, patent analysis employee affiliations, and foreign ownership. For example, DOT maintains a spreadsheet to track the status of due diligence activities for all awards, including risks that have been assessed for a small business’ cybersecurity practices, patents, employee affiliations, and foreign ownership. DOE also maintains a spreadsheet that provides the program office with real-time updates on the progress of the due diligence review and indicates when awards are cleared, declined, or still in progress.

In some instances, these agencies use automated systems to track the progress of applications through the review process, which includes due diligence. For example, both Air Force and NIH use software systems that track the status of applications throughout the pre-award review process. Their systems also alert program staff to applications that have not completed a due diligence step for a foreign risk review.

One agency (NSF) has minimally incorporated this practice. First, of the four risk areas in the Extension Act, the agency does not consistently conduct due diligence to address applicants’ cybersecurity practices for all new awards. NSF officials told us that program directors who have concerns about cybersecurity occasionally address these risks via direct questions or documentation requests from the applicant. However, such a process relies on the knowledge of individual program directors instead of agency guidance to address applicants’ cybersecurity practices.

Second, while NSF has established multiple procedures to conduct due diligence for the remaining three risk areas in the Extension Act, it does not track its activities in a consistent manner to ensure the process is completed for all new awards. For example, NSF officials noted that some of their program directors are using a web-based portal to send a standardized disclosure form to applicants, while others still collect and receive this document via email or through the agency’s internal grants management system.[23] These officials explained that they use multiple procedures to ensure due diligence is conducted on all new awards and that they do not need a single “master document” to track this process. However, we reviewed a snapshot of NSF’s grant management system used to track some applications during the review process and found that the system does not indicate (1) how risks in any of the four Extension Act areas are assessed or (2) the results of those assessments.

Without consistent procedures for conducting due diligence on all new awards, SBIR and STTR program staff may handle tasks differently, leading to varied and unpredictable outcomes. The SBA best practice states that agencies must perform due diligence for all new awards. By developing mechanisms to ensure all awards undergo due diligence, NSF can ensure any possible risks or threats have been identified and mitigated before federal funds are made available.

|

Encourage award recipients and applicants to leverage currently available and forthcoming federal research security training modules. Source: GAO analysis of agency information; toonsteb/adobestock.com (icons). | GAO‑26‑107972 |

Encourage education and training. Ten agencies (Air Force, DHS, DOE, DOT, Education, EPA, NASA, NIH, NSF, USDA) either encourage or require applicants to complete federal research security training, including additional cybersecurity training, such as by sending emails to applicants, posting on their websites, or including instructions in the solicitation. For example, NASA and NIH use newsletter distributions to notify applicants of available federal research security trainings. Other agencies, such as Air Force and DOE, encourage applicants and awardees to leverage publicly available trainings on topics such as foreign ownership and influence and small business information security. Additionally, in June 2025, NSF published a notice on its website stating that beginning in October 2025 the agency will require federal research security training from individuals listed as senior or key personnel on a proposal. According to NSF officials, this agency-wide guidance will apply to SBIR and STTR applicants.

Some of these agencies (DOT, Education, EPA, USDA) also require awardees to complete cybersecurity training as part of the award process. For example, DOT requires Phase II award recipients to complete a three-part cybersecurity training within 90 days of receiving the award notification.[24] After the training, the awardee must send proof of completion to the SBIR program office. Similarly, EPA and USDA also require all awardees to send proof of completion of cybersecurity training within two months or 10 days of receiving the award, respectively.

One agency (NOAA) has not incorporated this practice. NOAA officials told us they do not encourage applicants to leverage available federal research security training or education. The officials stated that due to staffing challenges, NOAA has not incorporated this best practice but plans to do so in the future. In November 2024, we reported about the importance of education and training for SBIR and STTR applicants, particularly on their potential vulnerabilities to cybersecurity threats and on available resources and guidance for cybersecurity.[25]

The SBA best practice states agencies should encourage award recipients and applicants to leverage currently available and forthcoming federal research security training modules. Encouraging awardees and applicants to leverage available federal research security guidance, training, and tools may help protect small businesses from cybersecurity threats and provide applicants with knowledge and tools to protect themselves against risks to their research.

|

Document the agency’s risk-based processes to due diligence factoring both the reputational and security risks presented by potential applicants. Source: GAO analysis of agency information; toonsteb/adobestock.com (icons). | GAO‑26‑107972 |

Document the risk-based processes to due diligence. Eight participating agencies (Air Force, DHS, DOT, Education, NASA, NIH, NOAA, USDA) have documented their risk-based approach to due diligence and established processes for identifying risks in cybersecurity practices, patent analysis, employee affiliations, and foreign ownership.[26] These documented risk-based approaches vary widely between agencies. Most of these agencies indicate their risk-based approach in a guidance document for program staff, detailing processes for incorporating due diligence into the agency’s existing SBIR and STTR program. For example, the DHS due diligence plan details several risk-based approaches, including performing an evaluation of potential risks associated with the topic before the solicitation is released. DHS also described a process to determine if the technology developed in the program would attract nefarious foreign actors who would seek to exploit it through copyright and data rights infringement.

Two agencies (DOE, EPA) have partially incorporated this practice. Both agencies have documented their approaches to due diligence but are missing one component of this practice. Specifically, DOE and EPA do not include any of the risk-based approaches suggested by the best practice in their documents.[27] Examples of these approaches include considering technology-based risk factors during its topic development process or considering tiered levels of risk. DOE officials explained that they have established a process to identify higher-risk topics before solicitations are published and maintain that they consider tiered levels of risk based on award phase. But these risk-based approaches are not documented in DOE’s due diligence plan. DOE officials further noted that the agency is still in the process of developing its complete due diligence process and plans to document its risk-based approach then.

In addition, EPA provided documentation from June 2023 indicating that the agency had considered multiple factors in documenting its risk-based process, but this risk-based approach is not noted in the current guidance manual that was updated in April 2025. EPA acknowledged that better linkages between the documents are needed to reinforce current guidance to program staff.

NSF has minimally incorporated this practice. NSF documented its approach to due diligence, but the document lacks details on a risk-based approach to cybersecurity practices.[28] We inquired about this issue, and NSF officials told us that program directors who have concerns about cybersecurity will address cybersecurity risks via direct questions or documentation requests from the applicant. NSF officials also noted that they do not have a specific written document that lays out their full due diligence procedures to conduct a risk assessment in the areas of cybersecurity, patent analysis, employee affiliations, and foreign ownership.[29]

The Extension Act requires agencies to (1) establish a due diligence program that uses a risk-based approach to assess risks in cybersecurity practices, patent analysis, employee affiliations, and foreign ownership and (2) incorporate to the extent practicable the applicable best practices—one of which is to document the agency’s risk-based approaches to due diligence. SBA’s best practices state that agencies should consider a variety of factors, including technology-based risk factors during the development of award topics for SBIR and STTR solicitations.

Without a due diligence plan that addresses the four risk areas, particularly those related to cybersecurity, it is unclear how agencies can ensure their SBIR and STTR programs are identifying and mitigating possible risks. Additionally, without clear documentation, program staff may not have a common understanding of roles, responsibilities, and processes intended to help small businesses address risks from illicit foreign actors. Such documentation can also mitigate the risk of limiting key institutional knowledge to a few personnel, such as in the event of staff turnover.

Some Agencies Have Incorporated Other Practices, but Gaps Remain

We found that some agencies have incorporated practices to explain that disclosure does not mean denial and to determine ‘covered individuals.’ However, gaps remain for other agencies.

|

Encourage disclosure by reassuring businesses that the disclosure of information related to foreign involvement or investment does not independently disqualify an applicant. Source: GAO analysis of agency information; toonsteb/adobestock.com (icons). | GAO‑26‑107972 |

Explain that disclosure does not mean denial. Seven participating agencies (Air Force, DOE, DOT, Education, EPA, NASA, NIH) explain to applicants that disclosing information required by the due diligence process does not mean denial.[30] Most of these agencies communicate this information to applicants in application materials. For example, DOE includes language in its SBIR and STTR grant application guide, while DOT communicates to applicants in both the solicitation and on the disclosure form itself that foreign involvement or investment does not independently disqualify applicants from receiving an award. Education explains in the solicitation that disclosed foreign affiliations or funding sources are not automatic grounds for declining a SBIR application and that the agency may require further mitigation measures after evaluating the potential risk.

Two agencies (NOAA, USDA) have minimally incorporated this practice. These agencies explain that “disclosure does not mean denial” through outreach events for applicants, but it is unclear whether information shared is communicated in a consistent manner. For example, NOAA officials noted that the SBIR program communicates this information at outreach events such as TechConnect, SBA Innovation Conferences, and NOAA’s SBIR Kickoff events. Similarly, USDA officials told us they communicate this information in webinars. However, this communication method does not ensure that the information is consistently communicated to applicants. NOAA officials stated that due to staffing challenges they have not incorporated this best practice but are planning to do so in the future. USDA officials stated that they had understood it would be sufficient to communicate “disclosure does not mean denial” through webinars but noted they can include this information in the upcoming solicitation and the terms and conditions of the award.

Two agencies (DHS, NSF) have not incorporated this best practice. Specifically, DHS explained that communicating this particular point would be inaccurate when the information disclosed could disqualify an applicant. In addition, NSF explained that a statement to the effect of “disclosure does not mean denial” seems redundant when awardees will undergo a due diligence process that already suggests some will receive awards and others will not.

The SBA best practice states that the disclosure of information related to foreign involvement or investment must be encouraged and such clarifications can reassure small businesses that foreign involvement does not independently disqualify them. Federal internal controls also state that agencies should communicate relevant and quality information to support their programs. Without clearly communicating to applicants that disclosing information will not automatically lead to a denial, agencies risk small businesses not providing the necessary information to determine whether there is a risk.

|

Consider the full range of individuals performing the award, to include as appropriate, postdoctoral fellows, subcontractors, and sub-grantees, in determining ‘covered individuals.’ Source: GAO analysis of agency information; toonsteb/adobestock.com (icons). | GAO‑26‑107972 |

Determine “covered individuals.”[31] Six participating agencies (Air Force, DHS, DOE, Education, NASA, NIH) have designated a list of “covered individuals” that must provide disclosure information to the agency. These agencies included the list of covered individuals in the solicitation or proposal instructions. For example, DOE’s solicitation specifies that consultants, graduate students, and postdoctoral associates are all considered covered individuals if they hold significant roles in the project. In another example, Air Force’s proposal submission instructions specify that covered individuals include key personnel such as direct employees, subcontractors, or consultants.

Two agencies (DOT, NOAA) partially incorporated this practice. NOAA includes a list of covered individuals in its due diligence plan, but the plan is an internal policy document to which applicants do not have access. NOAA’s materials for applicants, such as the solicitation, do not include this list. Similarly, DOT provides guidance on designating covered individuals—referred to as key personnel—in its due diligence plan, but this guidance is not in DOT’s materials for applicants. NOAA officials explained that due to staffing challenges they have not incorporated this practice and that they are working to incorporate it in the future. Further, DOT officials acknowledged that applicant materials do not include definitions of either key personnel or covered individuals.

Two participating agencies (EPA, USDA) minimally incorporated this practice. In interviews, these agencies described a list of designated covered individuals for their respective agencies but have not outlined these designations for applicants or program staff. EPA officials told us that their designation of covered individuals has changed since the first year of the due diligence program. According to officials, EPA’s designation now includes all employees of a potential awardee instead of just the principal investigator and the business representative. However, this designation is neither documented in EPA’s policies nor available to applicants. EPA officials stated that because the standardized disclosures are not required for all EPA SBIR applicants, they believed that the agency’s designation of covered individuals did not need to be in applicant-facing materials.

USDA officials told us they consider covered individuals or “key personnel” to include subcontractors, but the agency’s solicitation and award terms and conditions do not specify subcontractors in the definition of covered individuals. USDA officials stated that applicants should understand that subcontractors are included as covered individuals because they perform part of an award.

NSF has not determined its list of designated key personnel as covered individuals. We previously reported in November 2023 that NSF had intended to clarify this, but as of July 2025, the agency has not done so.[32] NSF officials stated that, for the purposes of foreign influence, all senior personnel are considered covered individuals. However, we found that this designation is neither documented in agency due diligence procedures nor available to applicants.

The SBA best practice notes that agencies are encouraged to consider the full range of individuals performing the award to minimize possible risks and include, as appropriate, postdoctoral fellows, subcontractors, or subgrantees as designated covered individuals. Federal internal controls also state that agencies should define information requirements clearly, in a specific and measurable way, where specific terms are fully and clearly set forth so they can be easily understood. A clear designation of covered individuals can help ensure that agencies are aware of the full scope of individuals performing the work and applicants are aware of who is required to provide foreign disclosures to identify possible risks.

Agencies Have Taken Some Steps to Mitigate the Reporting Burden and Refer Risks to Other Authorities

A few agencies have taken steps to mitigate the disclosure reporting burden and make referrals to enforcement authorities. We found most agencies have yet to make such referrals because risks have not risen to the level of requiring further action.

|

Leverage established reporting processes to capture updates to due diligence disclosures—such as requiring awardees to submit updated disclosures within 30 days of a substantive change—to reduce administrative burden for small businesses. Source: GAO analysis of agency information; toonsteb/adobestock.com (icons). | GAO‑26‑107972 |

Mitigate disclosure reporting burden. Three agencies (DOE, DOT, NIH) have incorporated SBA’s recommended steps to minimize updates to disclosure reporting.[33] NIH has incorporated several steps to minimize updates including (1) establishing a process for collecting unrelated updates (e.g., approval dates for human subject research) to the application without triggering a request to update the disclosure form; (2) requiring updates to the disclosure forms only when there is a change (e.g., a potential change in foreign affiliation or relationships to a foreign country) in the award that needs to be assessed; and (3) requiring the awardee to submit the updated disclosure within 30 days of a change as suggested by the SBA best practice.

The remaining eight agencies (Air Force, DHS, Education, EPA, NASA, NOAA, NSF, USDA) have partially incorporated this practice. These agencies have taken some of the recommended steps, such as requiring an updated disclosure form for Phase II awards. For example, EPA requires the disclosure form once for Phase I awardees and twice for Phase II awardees—once at the time of award and again after completion of year one of the contract—given its longer time frame and higher funding thresholds.

However, all eight agencies do not specify that updated disclosures must be provided within 30 days of any substantive changes to the project, as indicated by the best practice. DHS and NASA officials stated they had missed the 30-day portion of this best practice and plan to incorporate that wording in future solicitation cycles. EPA officials stated that this practice has not been a focus for its SBIR program, but they would consider incorporating it in the future. NOAA officials explained that due to staffing challenges, they have not incorporated this practice but will consider doing so in the future. Air Force officials had a different understanding of the 30-day requirement, and they noted that they could adjust their policy documents to better align with the best practice.

According to NSF officials, the reporting burden for this practice outweighs the benefits since NSF already (1) reevaluates awardee ownership each time additional funding is considered and (2) has enhanced its reporting and certifications requirements for Phase II awards. In addition, USDA officials told us they previously understood the 30-day reporting requirement could be communicated in webinars. But the officials agreed with our observation and noted that USDA could update the upcoming solicitation and award terms and conditions to include this information. Education did not provide a rationale for its lack of incorporation of the 30-day timeframe.

SBA’s best practice further states that agencies should require due diligence disclosure reporting to occur within 30 days of changes with covered individuals and any other substantive changes in circumstances. The Extension Act also requires awardees to report any changes to the required disclosures on foreign ownership and covered individuals throughout the duration of the award.[34] Incorporating information to provide a clear reporting timeframe would help ensure small businesses are providing timely updates to agencies during periods that may require renewed due diligence or otherwise introduce risk.

|

Evaluate if alternative authorities exist or further action is necessitated to adequately address any risks identified through the agency’s due diligence processes. Source: GAO analysis of agency information; toonsteb/adobestock.com (icons). | GAO‑26‑107972 |

Make referrals to appropriate enforcement authorities. Three agencies (Air Force, NASA, NSF) have established processes and made referrals to enforcement authorities based on adverse information resulting from due diligence activities. For example, Air Force officials told us that between March 2023 and June 2025, they referred 321 individual proposals to the Air Force Office of Special Investigations for counterintelligence reasons. One example of a referral provided by officials indicated that due diligence had identified business relationships with a foreign country of concern for a Phase II applicant. NSF referred a request to its Office of Inspector General for guidance concerning an applicant that had emails originating from a foreign email address though the entity had a U.S. zip code.

In addition, eight participating agencies (DHS, DOE, DOT, Education, EPA, NIH, NOAA, USDA) have taken steps to establish processes for making referrals to enforcement authorities or initiating further action if adverse information results from due diligence. For example, DHS, DOE, and NOAA officials described steps program staff would take to submit adverse due diligence findings to alternative authorities within their respective agencies. EPA’s due diligence plan outlines steps for documenting adverse findings with its Office of National Security, and officials told us they share this information with EPA’s Office of Inspector General. These eight agencies explained that, as of July 2025, they have yet to make such referrals because risks have not risen to the level of requiring further action. Therefore, we did not assess this practice at this time.

Most Agencies Assess Small Businesses’ Cybersecurity Practices, but Two Do Not

Most participating agencies and the selected components we reviewed assessed cybersecurity practices of small business applicants and aligned their assessment to federal cybersecurity frameworks.[35]

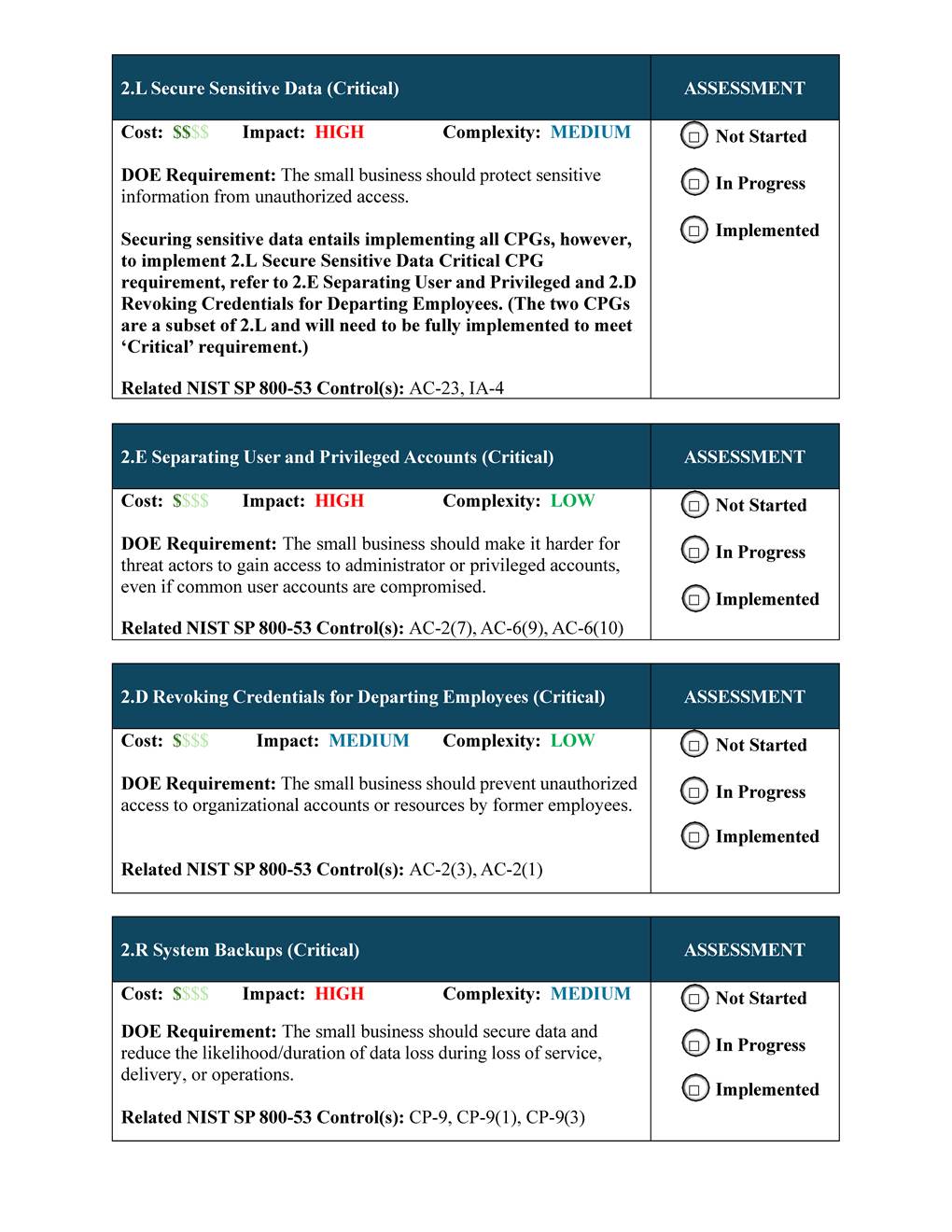

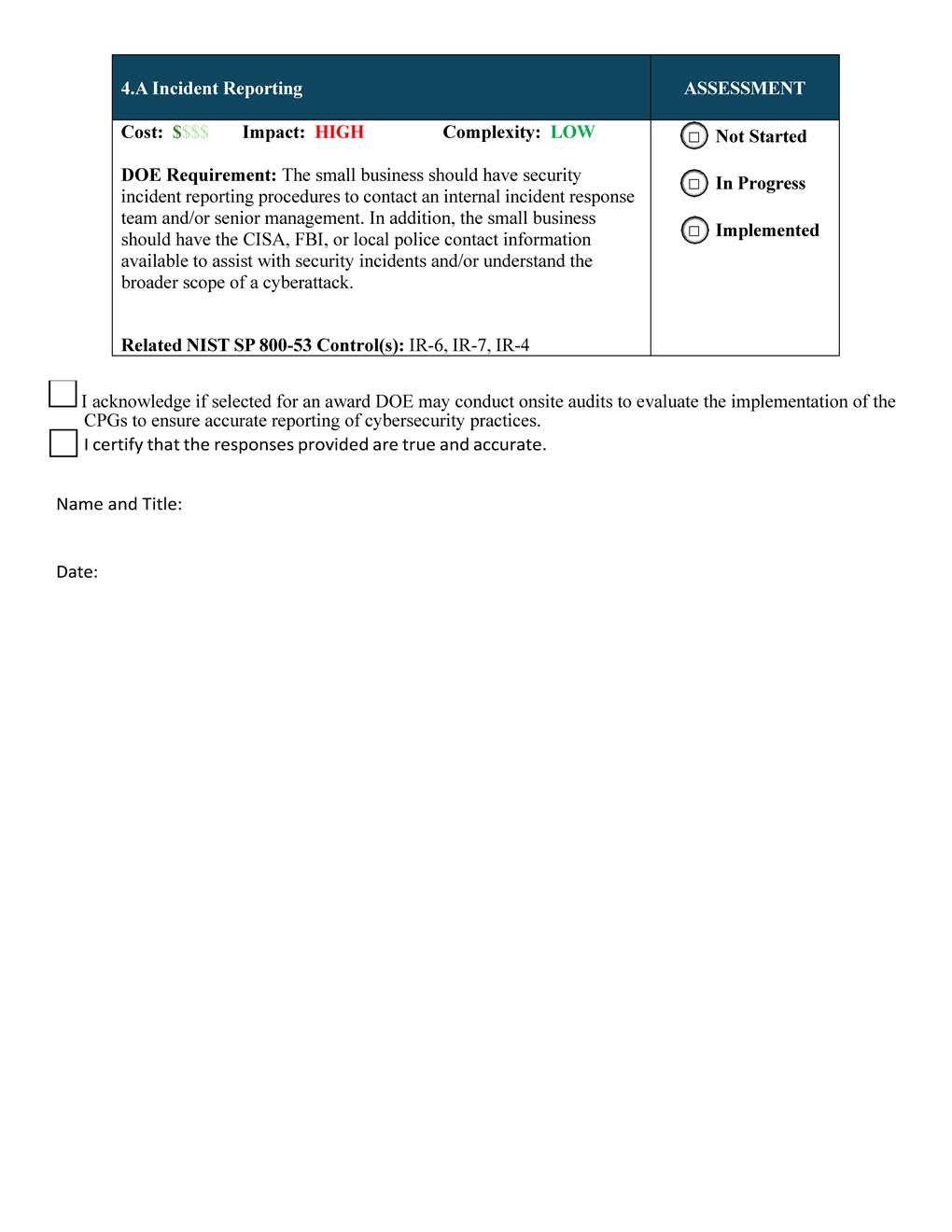

The Extension Act specifically required each agency to assess, using a risk-based approach as appropriate, the cybersecurity practices of a small business applicant.[36] Additionally, one of the SBA best practices also states that the agencies’ assessment of cybersecurity practices should (1) focus on basic small business safeguarding protocols and (2) remain consistent with federal cybersecurity frameworks. The best practice provided two such examples: the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) 52.204-21 Basic Safeguarding of Covered Contractor Information Systems and National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Small Business Information Security: The Fundamentals.[37]

We found nine of the 11 participating agencies and selected components we reviewed (Air Force, DHS, DOE, DOT, Education, EPA, NASA, NIH, NOAA) assessed small business applicants’ cybersecurity practices by using a variety of mechanisms, including business intelligence tools and self-assessment forms. Two remaining agencies (NSF and USDA) do not.

· Business intelligence tools. Eight agencies (Air Force, DHS, DOT, Education, EPA, NASA, NIH, NOAA) reported using business intelligence tools to assess small business applicants’ cybersecurity practices. Six of these agencies (Air Force, DHS, DOT, EPA, NASA, NOAA) use a specific tool that collects, processes, and analyzes data from externally observable sources to help inform agencies’ award decisions.[38] For example, the tool analyzes data from a small business’ IT footprint and provides a cybersecurity score. The score is a rating of an applicant’s security posture, which may indicate, for example, the likelihood of a successful data breach or cyberattack at the small business. This score is based on a combination of 10 cyber risk factors, such as network security and social engineering.[39]

Two additional agencies (Education, NIH) reported using other business intelligence tools in their cybersecurity assessments. Education officials stated that its supply chain risk management procedures include the use of an open-source intelligence tool that may provide cybersecurity vulnerability information to inform the agency’s overall risk determination. For example, the standard operating procedures include considerations for cyber vulnerability risk through an analysis, impact rating, and probability rating based on the number of publicly known vulnerabilities and known threats. NIH reported using six different software tools that can provide information about a small business, such as its exposure risk of unauthorized access to usernames or internet protocol traffic. At least one of the tools allows the agency to determine whether the small business is affiliated with certain countries, which may reveal if an applicant’s internet protocol address operates from a foreign country of concern.

· Self-assessment forms. Three of the nine agencies (DOE, NIH, NOAA) collect information from applicants to assess the cybersecurity practices of the small business.[40] For example, DOE requires applicants to complete a cybersecurity self-assessment form to inform DOE’s consideration of their cybersecurity practices, such as leadership responsible for cybersecurity, asset inventories, and the prevention of using default passwords. The form instructs applicants to examine their current cybersecurity practices and determine if the required cybersecurity performance goals are implemented.[41] In addition, NIH and NOAA require applicants to complete a questionnaire that asks whether the small business’ IT and information safeguarding plan ensures that it is applying basic cybersecurity protocols.

|

Agency cybersecurity assessments should focus on basic small business safeguarding protocols and remain consistent with federal cybersecurity frameworks. Source: GAO analysis of agency information; toonsteb/adobestock.com (icons). | GAO‑26‑107972 |

Ensure cybersecurity requirements are aligned with federal frameworks. As shown in figure 3, nine participating agencies and selected components (Air Force, DHS, DOE, DOT, Education, EPA, NASA, NIH, NOAA) aligned their cybersecurity assessments (i.e., business intelligence tools and self-assessment forms) with federal requirements and cybersecurity frameworks, in accordance with SBA’s best practice.[42]

Six of these agencies (Air Force, DHS, DOT, EPA, NASA, NOAA) reported using a business intelligence tool that aligned with federal requirements and cybersecurity frameworks. For some of these agencies, the business intelligence tool they use was originally deployed by the Air Force’s Office of Commercial and Economic Analysis (OCEA).[43] In June 2025, OCEA conducted an analysis of the tool and determined that it aligned with federal requirements and federal cybersecurity frameworks, such as FAR and NIST. For example, OCEA reported that the business intelligence tool included a scoring process that aligned with the 15 mandated security controls listed in the FAR 52.204-21, such as identifying, reporting, and correcting information and information system flaws in a timely manner.[44] In addition, OCEA also indicated that the tool aligned with the NIST cybersecurity framework’s identify, protect, and detect functions.[45]

Three agencies (DOE, NIH, NOAA) aligned their required self-assessment forms for applicants with a federal cybersecurity framework. For example, DOE’s cybersecurity self-assessment form for applicants uses a subset of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency’s Cybersecurity Performance Goals which links each assessment question to NIST’s Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations—another federal cybersecurity framework.[46] Specifically, one example from DOE’s form requires that small businesses prevent the use of default passwords to stop threat actors from achieving initial access or moving laterally in a network.

Furthermore, some agencies (Air Force, DHS, DOT, Education, NASA, NIH) told us they include contract clauses, provisions, or deliverables to, in part, align contract or award requirements with federal cybersecurity frameworks. For example, DOT’s due diligence plan states that the SBIR program will implement Transportation Acquisition Regulations through contract language within Phase I and II contracts. Specifically, the contract language includes requirements for data jurisdiction and adverse cyber event reporting. DOT officials stated that the use of contract language is one way to ensure a small business is aligned with a federal cybersecurity framework. In another example, NASA requires awardees to submit a system security plan that aligns with several federal cybersecurity frameworks.

However, two agencies (NSF, USDA) have not assessed the cybersecurity practices of small businesses; nor have they shown how such an assessment would be aligned to a federal cybersecurity framework.

NSF officials told us that NSF’s applicants are small and nascent companies with limited electronic assets or systems to protect. The agency explained that the program directors address cybersecurity concerns by asking questions or requesting documentation from applicants, as necessary. However, NSF did not document how program directors review small businesses’ cybersecurity practices , whether the outcomes of that review are tracked, or the extent to which the program directors’ assessment methods align with a federal cybersecurity framework.

USDA has access to a business intelligence tool that provides a cybersecurity grade for its applicants, but officials noted that they do not find the information useful and do not use it as a deciding factor for awards. These officials explained that their understanding was that the training of applicants would satisfy the requirement to assess the cybersecurity practices. USDA officials also stated that interagency discussions did not emphasize the importance of aligning cybersecurity assessments with federal frameworks. While training and education are two aspects of a cybersecurity control, those activities alone do not constitute a measure for assessing cybersecurity practices.

Until NSF and USDA incorporate cybersecurity assessments that are aligned with federal requirements and federal cybersecurity frameworks into their due diligence programs, the agencies are at an increased risk of making awards to small businesses that are vulnerable to cyberattack, including the theft of federally funded intellectual property.

SBA Could Leverage Interagency Meetings to Clarify Due Diligence Best Practices and Discuss Challenges Implementing Them

SBA conducts several information sharing meetings for agencies to discuss due diligence efforts, but we found agencies have gaps in how they have incorporated SBA’s best practices for due diligence programs to manage and reduce foreign risks. For example, some agencies are not incorporating certain best practices because, in part, they lack clarity on the intent of the practice or the best means to incorporate it. SBA has not facilitated such discussions on agency gaps in implementing SBA’s best practices for due diligence programs, which could help the agencies address possible risks.

SBA facilitates several interagency meetings to help participating agencies implement their SBIR and STTR programs. For example, after the enactment of the Extension Act in September 2022, SBA established weekly meetings, referred to as program managers committee meetings, to discuss the development of best practices and agencies’ due diligence programs.[47] In addition, SBA also facilitates monthly meetings with all participating agencies, referred to as program managers meetings, to discuss due diligence, among other topics.[48] For example, one meeting agenda included opportunities for agencies to share due diligence information on implementing cybersecurity training and automating the collection of disclosures.[49]

Furthermore, in January 2025, SBA established a bimonthly meeting, referred to as due diligence meetings, to have focused discussions on due diligence activities with all participating agencies.[50] At the inaugural meeting, participating agencies discussed topics such as approaches to educating small businesses, centralized due diligence tools, and the impacts of due diligence implementation (see sidebar). Officials from one agency (USDA) noted that participants also discussed the potential development of additional guidance on resources to carry out due diligence requirements. According to SBA officials, by March 2025, the discussion focus shifted away from agencies’ implementation of due diligence programs and toward the SBIR and STTR programs’ reauthorization legislation and its implications for agencies. SBA officials further noted that they anticipate reauthorization will be the primary focus of the due diligence meetings until the reauthorization bill is passed.

According to SBA officials, interagency meetings are the primary way participating agencies share information. Officials from some participating agencies and one selected component said these meetings were helpful for brainstorming ideas or leveraging the experience of other agencies in implementing due diligence programs.

Although the topics of these meetings address relevant aspects of the due diligence program, we found some agencies have gaps in their incorporation of SBA’s best practices, as discussed in prior sections of this report. For example, we found some agencies are not incorporating certain best practices because, in part, they lack clarity on the intent of the practice or the best means to incorporate it. As noted previously, eight agencies (Air Force, DHS, Education, EPA, NASA, NOAA, NSF, USDA) have not specified that updated due diligence disclosures must be provided within 30 days of any substantive changes to the project, as stated in the SBA best practice. These agencies have provided a variety of reasons for not doing so to date, but a few have stated they are considering implementing this portion of the best practice going forward. Agencies may need SBA’s emphasis on requiring these updates within 30 days as stated in the best practice.

In another example, DHS officials said they have not incorporated the “disclosure does not mean denial” best practice because including such a statement would be inaccurate. In their view, disclosure of such information could lead to a denial. NSF officials told us they have not incorporated this best practice because doing so seemed redundant relative to other parts of the due diligence process. In these cases, it appears DHS and NSF officials have a different understanding of how best to convey the message of this best practice. According to SBA’s best practice, it is to assure applicants are aware that disclosure of foreign investment or involvement does not independently disqualify them from receiving an award.

SBA officials told us they have had conversations with agencies on the best practices; however, in our discussions with participating agencies, officials from a few agencies said that additional discussion at SBA-facilitated meetings or additional guidance on these best practices would be helpful. The Extension Act requires participating agencies to incorporate applicable best practices in their due diligence programs to the extent practicable.[51] SBA is responsible for issuing policy directives and assisting participating agencies in implementing the SBIR and STTR programs, including the due diligence activities. According to the SBIR and STTR Policy Directive, SBA can make recommendations for improvement of participating agencies’ SBIR and STTR programs through its program managers meetings. For example, the Policy Directive states that SBA can make recommendations on a best practice currently being incorporated by an agency or provide open discussion and feedback on potential best practices for agency adoption.[52]

SBA officials acknowledged that based on observed implementation gaps and agency needs that we identified in this report, additional opportunities may exist for SBA to engage with agencies regarding challenges and impacts of incorporating the best practices and due diligence programs. Such discussions may also provide insights for possible revisions to the practices. By further leveraging its interagency meetings to facilitate such discussions, SBA could better assist agencies to (1) incorporate best practices, (2) identify implementation gaps and possible solutions, and (3) share best practices among agencies to help them better address the risks they face in implementing their SBIR and STTR programs.

Conclusions

Small businesses can expose U.S. federally funded R&D to foreign security risks, especially as certain foreign governments are actively working to illicitly acquire the most advanced U.S. technologies. SBIR and STTR participating agencies have taken steps to identify and mitigate possible foreign risks through their implementation of the due diligence programs to address security risks posed by small business applicants and through incorporation of SBA’s best practices for those programs.

However, we found gaps remain in most agencies’ incorporation of the full scope of these best practices. Furthermore, some agency officials noted that additional discussion or guidance on the practices in SBA-facilitated interagency meetings could be helpful. Such discussions could also provide clarity on the practices’ intent and how best to implement them. By leveraging its interagency forums to discuss these practices more frequently and in greater detail, SBA could help agencies improve their due diligence programs and protect against potential security risks from nefarious foreign actors.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making 26 recommendations to 11 agencies: one to the Air Force, two to DHS, one to DOE, one to DOT, one to Education, three to EPA, one to NASA, four to NOAA, seven to NSF, one to SBA, and four to USDA. Specifically:

The Secretary of Air Force should ensure the SBIR and STTR programs inform awardees in a written statement that updated disclosures must be provided within 30 days of any substantive changes to the project. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Agriculture should ensure the agency consistently communicates that disclosure does not mean denial to all its SBIR and STTR applicants through mechanisms such as disclosure form itself, the agency solicitation, or on a website as part of the application process. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Agriculture should ensure the agency clearly outlines its designation of “covered individuals” that is available to SBIR and STTR applicants and program staff to ensure consistent access and understanding. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Agriculture should ensure the SBIR and STTR programs inform awardees in a written statement that updated disclosures must be provided within 30 days of any substantive changes to the project. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of Agriculture should assess SBIR and STTR applicants’ cybersecurity practices, ensuring these assessments focus on basic small business safeguarding protocols and remain consistent with federal cybersecurity frameworks. (Recommendations 5)

The Secretary of Education should ensure the SBIR program informs awardees in a written statement that updated disclosures must be provided within 30 days of any substantive changes to the project. (Recommendation 6)

The Secretary of Energy should update its current SBIR and STTR due diligence plan—DOE Approach to SBIR/STTR Due Diligence—to include the agency’s risk-based approach for conducting due diligence, such as tiered levels of risk based on award phase and the process for identifying higher-risk topics before they are posted. (Recommendation 7)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the agency consistently communicates that disclosure does not mean denial to all its SBIR applicants through mechanisms such as disclosure form itself, the agency solicitation, or on a website as part of the application process. (Recommendation 8)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the SBIR program informs awardees in a written statement that updated disclosures must be provided within 30 days of any substantive changes to the project. (Recommendation 9)

The Secretary of Transportation should ensure the agency clearly outlines its designation of “covered individuals” that is available to SBIR and STTR applicants and program staff to ensure consistent access and understanding. (Recommendation 10)

The Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency should update its current SBIR due diligence plan—EPA’s SBIR Program Overview and Guidance Manual—to reflect the factors considered in documenting the agency’s risk-based approach. (Recommendation 11)

The Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency should ensure the agency clearly outlines its designation of “covered individuals” that is available to SBIR applicants and program staff to ensure consistent access and understanding. (Recommendation 12)

The Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency should ensure the SBIR program informs awardees in a written statement that updated disclosures must be provided within 30 days of any substantive changes to the project. (Recommendation 13)

The Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration should ensure its SBIR and STTR programs inform awardees in a written statement that updated disclosures must be provided within 30 days of any substantive changes to the project. (Recommendation 14)

The Director of the National Science Foundation should compile and track metrics on the impact of the SBIR and STTR due diligence requirements on award timeliness. (Recommendation 15)

The Director of the National Science Foundation should conduct due diligence on applicant cybersecurity practices for all new SBIR and STTR awards and develop a consistent method to track its due diligence activities. (Recommendation 16)

The Director of the National Science Foundation should ensure the agency consistently communicates that disclosure does not mean denial to all its SBIR and STTR applicants through mechanisms such as the disclosure form itself, the agency solicitation, or on a website as part of the application process. (Recommendation 17)

The Director of the National Science Foundation should update its current SBIR and STTR due diligence plan—NSF Updated Procedures for Risk-Based Due Diligence—to include its risk-based approach and procedures for conducting risk assessment in the four Extension Act areas (patent analysis, foreign ownership, employee affiliations, and cybersecurity. (Recommendation 18)

The Director of the National Science Foundation should ensure the agency clearly outlines its designation of “covered individuals” that is available to SBIR and STTR applicants and program staff to ensure consistent access and understanding. (Recommendation 19)

The Director of the National Science Foundation should ensure the SBIR and STTR program informs awardees in a written statement that updated disclosures must be provided within 30 days of any substantive changes to the project. (Recommendation 20)

The Director of the National Science Foundation should assess SBIR and STTR applicants’ cybersecurity practices, ensuring these assessments focus on basic small business safeguarding protocols and remain consistent with federal cybersecurity frameworks. (Recommendations 21)

The Under Secretary for Oceans and Atmosphere should direct the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to encourage SBIR award recipients and applicants to leverage available federal research security training. (Recommendation 22)

The Under Secretary for Oceans and Atmosphere should ensure the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration consistently communicates that disclosure does not mean denial to all its SBIR applicants through mechanisms such as disclosure form itself, the agency solicitation, or on a website as part of the application process. (Recommendation 23)

The Under Secretary for Oceans and Atmosphere should ensure the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration SBIR program clearly outlines its designation of “covered individuals” that is available to applicants and program staff to ensure consistent access and understanding. (Recommendation 24)

The Under Secretary for Oceans and Atmosphere should ensure the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration informs SBIR awardees in a written statement that updated disclosures must be provided within 30 days of any substantive changes to the project. (Recommendation 25)

The Administrator of the Small Business Administration should further leverage its SBIR and STTR interagency meetings and communications to facilitate discussions on due diligence best practices, including clarifying the intent of the practices and discussing implementation methods to help agencies address their gaps in incorporating the practices. (Recommendation 26)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to Commerce, DHS, DOD, DOE, DOT, Education, EPA, HHS, NASA, NSF, SBA, and USDA for review and comment. Commerce, DHS, DOD, DOE, DOT, Education, EPA, NASA, NSF, and USDA concurred with our recommendations, and their written responses are reprinted in appendices III through XII. In an email response on December 18, 2025, SBA officials stated their concurrence with our recommendation to SBA. DOE, DOT, HHS, NASA, NSF, and SBA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. For example, SBA stated in its technical comments that the report suggests that SBA is responsible for addressing the gaps in agencies’ incorporation of the due diligence best practices. We agree that participating agencies are responsible for addressing these gaps. We adjusted language in the report to clarify that SBA could leverage its interagency meetings to help agencies address their gaps in incorporating SBA’s best practices.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees; the Secretaries of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and Transportation; the Administrators of the SBA, EPA, and NASA; the Director of the NSF; and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at wrightc@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix XIII.

Candice N. Wright

Director, Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics

List of Committees

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Joni Ernst

Chair

The Honorable Ed Markey

Ranking Member

Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Brian Babin

Chairman

The Honorable Zoe Lofgren

Ranking Member

Committee on Science, Space, and Technology

House of Representatives

The Honorable Roger Williams

Chairman

The Honorable Nydia M. Velázquez

Ranking Member

Committee on Small Business

House of Representatives

The SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) and STTR (Small Business Technology Transfer) Extension Act of 2022 includes provisions for GAO to issue a series of reports on the implementation and best practices of agencies’ due diligence programs to assess security risks presented by small businesses seeking a federally funded award.[53] This report, the third in the series, examines (1) the extent to which agencies are incorporating the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) best practices for the SBIR and STTR due diligence programs; (2) the extent to which agencies assess cybersecurity practices of small businesses seeking SBIR and STTR awards; and (3) the mechanisms that exist for agencies to share information on practices, risks, and challenges in their SBIR and STTR due diligence programs.

The scope of work includes the SBA and the 11 participating agencies.[54] For the five agencies with more than one component that issues SBIR and STTR awards, we selected the component that issues the highest volume of awards annually based on fiscal year (FY) 2023 award data, which were the most complete data available at the time of our review. Specifically, we focused on the Department of the Air Force in the Department of Defense (DOD), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the Department of Commerce (Commerce). We refer to these three component entities throughout the report inclusively in our “participating agencies” (i.e., Air Force, NIH, and NOAA).

In addition, the Science and Technology Directorate in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Office of Science in the Department of Energy (DOE) both issue the most SBIR and STTR awards for their agencies and oversee these programs on behalf of other components in their agencies; therefore, we refer to the parent agency (DHS and DOE, respectively) in our collective “participating agencies.”[55]