CYBERSECURITY

Independent Assessment and VA Response Generally Met Requirements

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Jennifer Franks at franksj@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Based on a requirement in the Strengthening VA Cybersecurity Act of 2022, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) contracted with MITRE to perform a cybersecurity assessment. The subsequent assessment addressed the requirements in the act and aligned with federal guidance. For example, MITRE appropriately (1) selected for review five key systems that, if compromised, could severely impair VA’s ability to execute its mission, and (2) evaluated the effectiveness of VA’s information security program.

VA submitted a plan to remediate the findings identified by the assessment that generally addressed the requirements in the act. Specifically, the remediation plan included a cost estimate and implementation timelines to address the system and security program findings. The remediation plan also included planned improvements to VA’s security program. While the remediation plan did not include improvements to system-specific security controls, VA provided details on those plans in other documents.

VA has reported progress in remediating findings across the five systems and its security program. Specifically, the department reported remediating 215 of 442 system-specific findings by October 2024 and remediating 379 findings by July 2025 (see figure). Also, the department reported that it had completed 20 of 55 actions to address the 11 information security program findings.

VA generally documented remediation efforts for the system and program findings in accordance with federal requirements. However, it did not always update its remediation plans. For example, for one system, VA did not update the remediation date for a high-risk vulnerability that was 15 months past due. Similarly, the department did not update estimated remediation dates for at least two program findings. Further, although plans were in place, remediation efforts were not timely. Specifically, as of July 2025, VA had not remediated two high-risk vulnerabilities—those with the most severe consequences—over a 17 to 21-month period, although its policy is to remediate them within 60 days.

VA’s Inspector General has previously made recommendations to VA to (1) ensure the department tracks and updates planned remediation documents and (2) improve the process for resolving vulnerabilities that cannot be addressed within policy timeframes by ensuring implementation of mitigating controls. As of July 2025, VA had not yet implemented these recommendations. Doing so would help ensure that needed actions are taken to protect systems.

Why GAO Did This Study

VA depends on critical IT systems to manage benefits and provide health care to veterans and their families. VA’s highly networked and technologically diverse systems create unique cybersecurity complexities. Protecting these systems from cyber threats is imperative.

The Strengthening VA Cybersecurity Act of 2022 includes a provision for GAO to evaluate an independent cybersecurity assessment and VA’s remediation plan in response to the assessment. This report examines the extent to which (1) the independent cybersecurity assessment addressed the act and federal guidance, (2) VA’s remediation plan adhered to the act, (3) the department reported remediating the assessment’s findings, and (4) VA’s efforts to remediate selected findings adhered to federal requirements.

To address these objectives, GAO compared MITRE’s assessment of selected systems and the overall information security program, as well as VA’s remediation plan, against requirements in the act. GAO also summarized VA’s reported remediation progress for the assessment findings. In addition, GAO compared VA’s efforts to remediate findings against federal requirements. Further, GAO interviewed relevant MITRE and VA officials.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

FFRDC |

Federally Funded Research and Development Center |

|

FISMA |

Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 |

|

IT |

information technology |

|

NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

OIS |

Office of Information Security |

|

OIT |

Office of Information and Technology |

|

SVAC Act of 2022 |

Strengthening VA Cybersecurity Act of 2022 |

|

VA |

Department of Veterans Affairs |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 11, 2025

The Honorable Jerry Moran

Chairman

The Honorable Richard Blumenthal

Ranking Member

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Bost

Chairman

The Honorable Mark Takano

Ranking Member

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

House of Representatives

Federal agencies, including the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), rely extensively on IT to carry out their operations and deliver services to constituents. Federal IT systems, including those of VA, are often interconnected with other internal and external systems, highly networked, and technologically diverse. This complexity increases the difficulty in identifying, managing, and protecting the numerous operating systems, applications, and devices comprising the systems and networks.

Accordingly, since 1997 we have designated federal information security as a government-wide high-risk area. This area was expanded to include the protection of critical cyber infrastructure in 2003 and the privacy of personally identifiable information in 2015. In addition, we designated VA health care as a high-risk area for the federal government in 2015, in part due to the department’s IT challenges.[1]

Congress passed the Strengthening VA Cybersecurity Act of 2022 (SVAC Act of 2022). The act required VA to (1) enter into an agreement with a Federally Funded Research and Development Center (FFRDC) to provide an independent cybersecurity assessment and (2) develop a remediation plan to address the assessment’s findings.[2] The Secretary of VA entered into an agreement with the MITRE Corporation (MITRE) to perform the assessment.

The act also includes a provision for us to review the cybersecurity assessment performed by MITRE and the department’s response plan to address the assessment findings. Specifically, our objectives were to evaluate the extent to which the (1) independent cybersecurity assessment addressed the requirements in the SVAC Act of 2022 and aligned with federal guidance, (2) department’s plan to address the assessment’s findings adhered to the SVAC Act of 2022, (3) department reported remediating the assessment’s findings, and (4) department’s efforts to remediate selected findings adhered to federal requirements.

To address the first objective, we identified the act’s requirements for the independent assessment. The act required MITRE to review five high-impact systems[3] and the effectiveness of VA’s information security program.[4] We then reviewed details in MITRE’s cybersecurity assessment report to understand how MITRE selected the five high-impact systems. We collected and reviewed VA artifacts, such as VA’s critical system list and system security plans, to determine if MITRE’s selection of five high-impact systems complied with the act. We also reviewed the assessment report to determine if the five systems MITRE selected included system characteristics required in the act.

Further, we analyzed MITRE’s assessment report to determine how they organized the assessment to evaluate the effectiveness of the information security program. We reviewed how MITRE mapped the organization of their program assessment approach to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework 2.0.[5] We also reviewed details in the report explaining how MITRE included the required evaluation of shadow IT as part of the program assessment.[6]

In addition, we reviewed the assessment report to determine the extent to which MITRE used industry best practices for the assessment methodology, as required by the act. We also supplemented our review of MITRE’s use of best practices by comparing assessment methods discussed in the report to NIST guidance on conducting cybersecurity assessments.[7] Further, we analyzed MITRE’s assessment report to determine if it developed conclusions from its assessment findings that addressed VA’s ability to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information systems and protect against the threats listed in the act. We also interviewed MITRE officials to clarify the assessment’s scope and methodology.

To address the second objective, we reviewed VA’s response plan to address MITRE’s findings on the five high-impact systems, as well as the information security program. Specifically, we compared VA’s plan to the act’s requirements to have a cost estimate, estimated remediation timeline, and planned improvements to security controls for the five reviewed systems and the program.

For the third objective, we summarized VA’s reported progress to address the system and program findings. Specifically, we assessed VA’s remediation plan submitted to Congress to determine the remediation status of the system and program findings as of October 2024. For the system findings, VA officials provided us updates to the status of remediated vulnerabilities in March 2025 and July 2025. For the information security program findings, we collected outputs from VA’s audit tracking portal in May 2025 and July 2025 to determine the status of reported remediation efforts.

To address the fourth objective, we determined the extent to which VA documented planned remediation for the system and program findings according to NIST requirements.[8] We selected NIST requirements that pertained to documenting planned remediation for identified vulnerabilities.

· To assess the system findings, we first reviewed VA’s policy to determine if it reflected NIST requirements.[9] We aggregated assessment data provided by MITRE with remediation data provided by VA to identify the findings that were not remediated as of March 2025. We focused our analysis on high-risk and moderate-risk vulnerabilities that VA had not remediated because its policy defines remediation timelines for these vulnerabilities.[10] Specifically, we compared the date these vulnerabilities were identified to the date they were to be completed based on VA’s remediation time frames. If the vulnerabilities had exceeded the required remediation date, we determined if VA had created plans of action and milestones in accordance with NIST and VA requirements. We collected and reviewed updated remediation data from VA in March 2025, May 2025, and July 2025.

We assessed the reliability of remediation data related to the system findings by reviewing the data from VA’s remediation tracking system and interviewing agency officials knowledgeable about the data. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report.

· To assess the program-related findings, we determined if the documentation of planned remediation included planned remediation actions, an updated remediation status, and estimated remediation timelines for each finding, in accordance with NIST requirements. We also interviewed officials to understand how VA documented and tracked the program findings.

Further, we reviewed VA Office of Inspector General (OIG) reports to identify findings and recommendations made by the OIG relating to the timely remediation of vulnerabilities and the documentation of plans of action and milestones. We also reviewed VA OIG’s website to determine the implementation status of relevant recommendations.

We conducted this audit from December 2024 to December 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

VA is responsible for providing a variety of services to veterans and their families (i.e., spouses and children), including health care, disability compensation, and vocational rehabilitation. For example, within the department, the Veterans Health Administration oversees the delivery of health care services, including primary care, specialized care, and related medical and social support. These services are provided at its more than 1,300 medical facilities located throughout the country.

The use of IT is crucial to helping VA carry out its operations and deliver services to constituents. Specifically, VA relies on IT systems and networks to receive, process, and maintain sensitive data, including veterans’ medical records. It maintains this information in a variety of systems, such as its electronic health records system, to support the delivery of health care to veterans.

VA’s increased dependence on IT can lead to vulnerabilities that may compromise sensitive personal information, such as inappropriate use, modification, or disclosure. As a result, the corruption of data or the denial or delay of services for veterans due to compromised IT systems and electronic information can create undue hardship for veterans and their dependents. In light of these risks, implementing an effective information security program and controls is important for VA in protecting the sensitive health data of veterans.

VA’s Office of Information and Technology (OIT) delivers technologies and services to support veterans. Specifically, OIT includes service organizations that provide IT services for the department. One of these service organizations, the Office of Information Security (OIS), is responsible for protecting VA resources and securing sensitive data of veterans.

Laws and Guidance Support Federal Cybersecurity

Federal laws—including the Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 (FISMA)—and guidance specify requirements for protecting the security of federal information and systems, including those that VA uses to store veterans’ health data.

· FISMA. FISMA provides a comprehensive framework for ensuring the effectiveness of information security controls over federal operations and assets.[11] FISMA assigns responsibility to each agency head for providing information security protections commensurate with the risk and magnitude of the harm. Security risks include unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction of information systems used or operated by an agency or by a contractor of an agency or other organization on behalf of an agency. The law also requires each agency to develop, document, and implement an agency-wide information security program to provide risk-based safeguards for the information and information systems that support the operations and assets of the agency.

· NIST guidance. FISMA requires agencies to comply with NIST standards, including minimum information security requirements as described in NIST Special Publication 800-53, Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations.[12] This publication provides a catalog of security and privacy controls for federal information systems and a process for selecting controls to protect organizational operations and assets. For example, the publication requires vulnerabilities to be remediated according to organization-defined time frames based on an assessment of risk. Further, NIST Special Publication 800-53A, Assessing Security and Privacy Controls in Information Systems and Organizations, provides guidance for assessing the effectiveness of security controls defined in NIST Special Publication 800-53.[13]

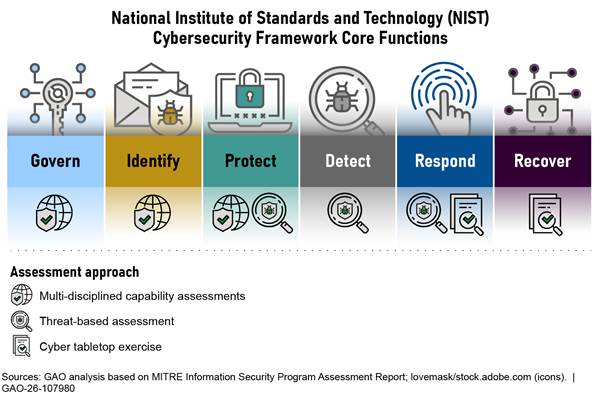

· NIST cybersecurity framework. In May 2017, the President issued an executive order[14] requiring agencies to immediately begin using NIST’s cybersecurity framework for managing their cybersecurity risks.[15] The framework provides guidance for cybersecurity activities based on six core security functions:

· Govern – develop a cybersecurity risk management strategy and policies.

· Identify – develop the organizational understanding to manage cybersecurity risk to systems, assets, data, and capabilities.

· Protect – develop and implement the appropriate safeguards to ensure delivery of critical infrastructure services.

· Detect – develop and implement the appropriate activities to identify the occurrence of a cybersecurity event.

· Respond – develop and implement the appropriate activities to act upon a detected cybersecurity event.

· Recover – develop and implement the appropriate activities to maintain plans for resilience and to restore any capabilities or services that were impaired due to a cybersecurity event.

GAO Previously Made Recommendations to Improve Cybersecurity Risk Management

In April 2023, we testified on security challenges that VA has faced in safeguarding its information systems based on prior reporting.[16] For example, in July 2019, we reported that agencies, including VA, did not fully establish elements of a cybersecurity risk management program.[17] Specifically, VA did not develop a risk management strategy or conduct agencywide risk assessments as part of its cybersecurity risk management program. We made four recommendations to VA to ensure that VA establish the required elements for agencywide cybersecurity risk management programs. VA has implemented these recommendations.

Mandate Required VA to Contract for Cybersecurity Assessment

The SVAC Act of 2022 required the Secretary of VA to enter into an agreement with an FFRDC to provide an independent cybersecurity assessment. As part of this assessment, the FFRDC was to evaluate five high-impact information systems of the department. In addition, the FFRDC was to assess the effectiveness of the department’s information security program. The act also called for the Secretary to develop a plan to address the findings identified by the FFRDC and submit the plan to the Senate and House Committees on Veterans’ Affairs.

In May 2023, VA contracted with MITRE to perform the independent cybersecurity assessment. MITRE is a not-for-profit research organization that operates six FFRDCs and supports federal government operations in areas such as cybersecurity. MITRE completed the assessment report on April 30, 2024, and delivered it to the Secretary on June 12, 2024.[18] The Secretary submitted a plan to the committees in October 2024.[19]

MITRE, VA OIG, and VA Testified on the Status of VA Cybersecurity

In November 2024, the House VA Subcommittee on Technology Modernization held a hearing with officials from MITRE, VA OIG, and VA. In its testimony, MITRE summarized its assessment findings and recommendations resulting from the review of five high-impact systems and evaluation of the information security program.[20] MITRE reported that for the five high-impact systems, VA applied standard cybersecurity protections that aligned with NIST guidance and VA policy.

However, MITRE identified 442 findings in the five systems assessed.[21] MITRE noted that the findings demonstrated that VA needed to improve how it applied software patches, configured operating systems and databases, enforced access control, secured software development practices, and logged events to detect cyber-attacks. MITRE considered 29 of these 442 findings to be high-risk vulnerabilities.

Further, MITRE found systematic challenges with the information security program that MITRE grouped into 11 finding areas, as shown in table 1.

Table 1: MITRE Identified 11 Finding Areas for the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Information Security Program

|

Finding |

Description |

|

Office of Information Security Customer Service to Systems Teams |

Office of Information Security teams that provide security services to system-level teams did not effectively communicate and coordinate together, hindering effective cybersecurity implementation. |

|

Cybersecurity Governance |

Siloed operations and outdated policies affect overall cybersecurity effectiveness. |

|

Cybersecurity Risk Management |

VA needs to make improvements to mature beyond compliance activities. |

|

Information System Security Officer and System Steward Roles |

Information System Security Officer roles need to be aligned with specific systems (e.g., infrastructure, medical devices). |

|

Continuous Monitoring |

VA needs to make improvements in control assessments, vulnerability scanning, configuration compliance, and software management. |

|

Medical Devices |

VA faces challenges in quickly addressing vulnerable medical devices and maintaining security over the life of these devices. |

|

Cloud Security |

VA needs to consistently apply cloud configurations. |

|

Shadow IT |

Shadow IT introduces unaccounted-for risk. |

|

Cyber Protection |

VA can enhance protections by implementing zero trust architecture.a |

|

Cyber Detection |

VA has opportunities to optimize tools, alert triggers, and integration capabilities. |

|

Response and Recovery |

Siloed organizations and manual operations hinder VA’s ability to maintain mission continuity. |

Source: GAO analysis based on MITRE Written Testimony on November 20, 2024. | GAO‑26‑107980

aA zero trust architecture is a set of cybersecurity principles stating that organizations must verify everything that attempts to access their systems and services.

Based on the 11 finding areas, MITRE issued 35 recommendations to improve VA’s overall information security program, including priority recommendations related to enhancing VA’s risk management framework and reducing shadow IT to mitigate cybersecurity risk.

In its statement, VA OIG highlighted the evaluation conducted for its fiscal year 2023 FISMA audit report, issued in May 2024.[22] VA OIG found that though VA had made some progress in certain areas of its security program, VA OIG continued to identify deficiencies that it had found in previous audits related to the inadequacy and ineffectiveness of VA information security controls. Specifically, the OIG identified that VA faced continued challenges in implementing components of its agencywide information security risk management program to meet FISMA requirements. Further, similar to what MITRE found in its assessment, VA OIG noted ongoing significant deficiencies related to the controls for configuration management and access control.

At the hearing, the VA Assistant Secretary for Information and Technology noted the department’s efforts to deploy various cybersecurity capabilities to defend against cyber threats and improve the department’s cybersecurity program.[23] He also noted steps the department has taken to implement a zero trust architecture as part of its cybersecurity strategy.[24] Further, he emphasized that MITRE’s report did not identify a substantial number of new findings. Specifically, he noted that many of MITRE’s overall findings had already been identified during VA OIG’s previous enterprise-wide audits, including the annual FISMA audit.

MITRE’s Cybersecurity Assessment Addressed the Act’s Requirements and Aligned with Federal Guidance

MITRE’s assessment of VA’s cybersecurity addressed the requirements in the act. Specifically, MITRE appropriately selected five high-impact systems for their VA cybersecurity assessment. MITRE also evaluated the effectiveness of VA’s information security program including how the department used shadow IT. Further, MITRE incorporated industry best practices in the assessment methodology, as required by the act. In addition to following best practices, MITRE adhered to NIST guidance as part of its assessment methodology. Lastly, based on assessment findings from the five systems and the program, MITRE analyzed the department’s ability to achieve the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of systems and defend against various cyber threats.

MITRE Appropriately Selected Five Systems for the Cybersecurity Assessment

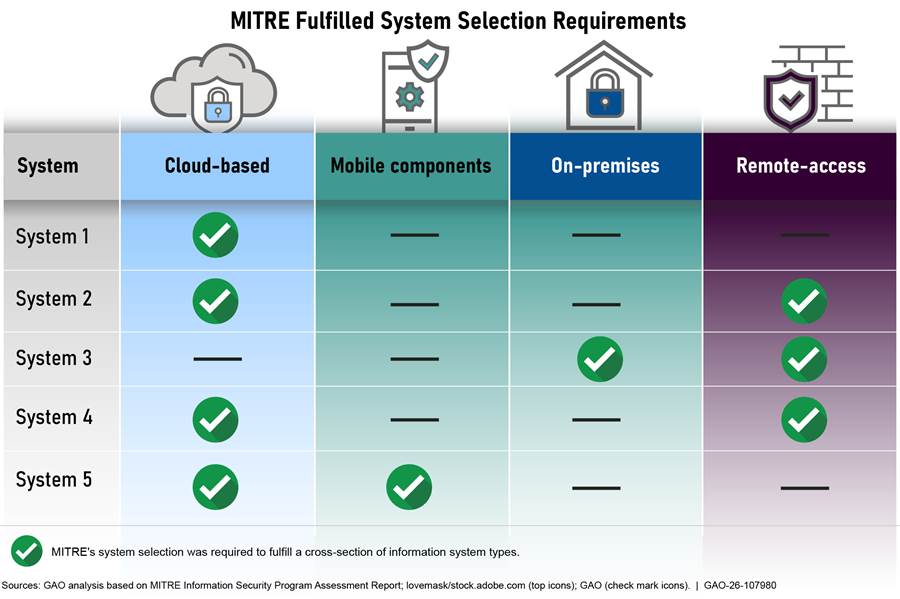

The act required MITRE to select five high-impact systems for its cybersecurity assessment. The act also required that the selection of these five systems include a cross section of systems that are on-premises, remotely-accessed, cloud-based, and that include mobile components.[25]

MITRE appropriately selected high-impact systems to assess based on requirements in the act. MITRE used VA’s critical systems inventory as a basis to select systems that were essential to VA operations and selected systems that had an overall risk score of high or moderate.[26] MITRE then used the high-impact categorization guidelines from the Committee on National Security Systems Instruction 1253 to eliminate systems that they did not consider to be high impact.[27]

Once MITRE identified VA’s high-impact systems, it selected five systems that encompassed on-premises, remote, cloud-based, and mobile systems, as required by the act. MITRE’s assessment report indicated that each of the selected systems’ environments aligned with at least one of the areas required in the act, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Characteristics of the Department of Veterans Affairs High-Impact Systems Selected for MITRE’s Cybersecurity Assessment

As discussed later in this report, MITRE assessed the cybersecurity protections

for these five systems.

MITRE Assessed the Effectiveness of VA’s Information Security Program and the Department’s Use of Shadow IT

The act required MITRE to assess the effectiveness of the department’s information security program. The act also required the assessment of the program to include an evaluation of the department’s use of shadow IT.

MITRE assessed program effectiveness by organizing the evaluation into three distinct assessment approaches based on areas of organizational challenge and risk:

· Multi-disciplined capability assessment – MITRE evaluated various capability areas, such as asset management and cloud security, to determine VA’s implementation of these capabilities within programmatic functions across VA organizations that have cybersecurity responsibilities.

· Threat-based cyber assessment – MITRE evaluated VA’s implementation of protective, detective, and response controls. It (1) identified specific threat actors that presented the highest risk to VA’s mission, (2) analyzed cyber tools, such as those associated with logging cybersecurity events, and (3) tested VA networks by emulating specific threat actors to evaluate VA preparedness for protecting against the cyber threats MITRE identified as highest risk and those listed in the act.

· Cyber tabletop assessment – MITRE conducted a cyber tabletop exercise at a VA medical center site simulating a downtime event to assess the department’s ability to ensure mission continuity and coordinate response and recovery resulting from a cyber incident.

MITRE aligned these assessment approaches to the six core functions in the NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0, which provides guidance for managing cybersecurity risk to agency officials responsible for developing and leading information security programs.[28] MITRE included in its assessment report a mapping of the six core cybersecurity functions to the three assessment approaches, as shown in figure 2:

Figure 2: Mapping of National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework 2.0 Core Functions to MITRE Program Assessment Approaches

MITRE’s program assessment also included an evaluation of the department’s use

of shadow IT. MITRE assessed shadow IT through the multi-disciplined capability

assessment, particularly through the asset management capability area.

Specifically, it conducted a series of interviews with officials from OIT and

OIS to understand VA’s management of shadow IT. It also analyzed a VA tool that

monitors networks for cyber threats and vulnerabilities to align systems found

on the tool with the system authorization status. MITRE determined that, while

OIT has a program in place to manage shadow IT, VA is not able to manage

related challenges using current processes.

MITRE Incorporated Industry Best Practices and NIST Guidance in Its Assessment Methodology

The act required MITRE to take into account industry best practices for the assessment methodology. Best practices include industry standard cybersecurity tools and frameworks used to assess systems and program security.

MITRE incorporated industry best practices as part of the assessment methodology for assessing the five selected systems and the information security program. It used various industry standard cybersecurity assessment tools to conduct hands-on technical vulnerability assessments for the selected systems’ application and infrastructure. For example, it used these assessment tools to perform testing on application data and complete automated scanning of system infrastructure.

Further, for the program assessment, MITRE used their industry standard Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge (ATT&CK) framework as part of the methodology for the threat-based assessment.[29] Specifically, MITRE used the framework to analyze VA cybersecurity tools and procedures and design adversary emulation testing activities to evaluate VA’s ability to protect, detect, and respond to cyber threats, such as those listed in the act, as discussed later in this report.

MITRE’s Assessment Methodology Followed NIST Guidance

In addition to using best practices, MITRE adhered to NIST guidance in its assessment methodology. According to NIST guidance for evaluating cybersecurity controls, assessors should use the following methods to outline the actions taken in performing the assessment:

· Examine – the process of reviewing or analyzing one or more assessment objects to facilitate understanding or obtain evidence.

· Interview – the process of holding discussions with individuals in an organization to facilitate understanding and obtain evidence.

· Test – the process of exercising assessment objects under defined conditions to compare the actual state of the object to the desired state of the object.

Specifically, as shown in table 2, MITRE’s assessment methodology for evaluating the five systems and the program included the three assessment methods for performing cybersecurity evaluations, in accordance with NIST guidance.

Table 2: MITRE’s Use of National Institute of Standards and Technology Assessment Methods to Evaluate Five High-Impact Systems and the Information Security Program at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)

|

Method |

Five high-impact systems assessment |

Information security program assessment |

|

Examine |

MITRE began the five systems assessment by collecting and examining information on the systems. For example, it observed a demonstration of the systems in operation before testing software components. |

As part of the multi-disciplined capability assessment, MITRE examined 106 source artifacts documenting policies and procedures. It also reviewed documentation to analyze VA cybersecurity tools as part of the threat-based cyber assessment. |

|

Interview |

MITRE conducted interviews with officials from VA responsible for operating VA’s cybersecurity capabilities. It also conducted interviews with system security teams such as those responsible for configuration management, to determine root causes of assessment findings. |

As a part of the multi-disciplined capability assessment, MITRE conducted 45 interviews across VA organizations with cybersecurity responsibilities. In addition, as part of the threat-based cyber assessment, it interviewed officials from the VA cybersecurity operations center to understand how VA cybersecurity tools were used to detect cyber threats. |

|

Test |

MITRE conducted systems testing through a series of vulnerability scans, configuration checks, and execution of custom test scripts on the selected systems. It developed five assessment reports for each of the systems to document identified vulnerabilities resulting from the tests. |

As a part of the multi-disciplined capability assessment, MITRE conducted independent testing on VA cyber monitoring tools to validate statements made during interviews with VA officials. In addition, as part of the threat-based cyber assessment, it conducted testing on operational VA networks to assess VA’s cyber detection coverage against various cyber threats. Further, it conducted a cyber tabletop exercise to evaluate VA’s ability to respond and recover from cyber events that affect the continuity of operations. |

Source: GAO analysis based on MITRE Information Security Program Assessment Report. | GAO‑26‑107980

MITRE Included Required Analysis Based on Assessment Conclusions

The act required the assessment to include analysis of the department’s ability to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information systems and protect against cyber threats. Based on findings from evaluating the five high-impact systems and the information security program, MITRE analyzed and drew conclusions on the department’s ability to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information systems. MITRE also analyzed the department’s ability to protect against the cyber threats listed in the act. Specifically:

· Advanced persistent cyber threats – MITRE analyzed the threat-based cyber assessment of the information security program, particularly findings resulting from testing networks through the emulation of specific threat actors. MITRE also corroborated these conclusions with evidence from the system assessments.

· Ransomware – MITRE drew conclusions from adversary emulation exercises associated with the threat-based cyber assessment and the ransomware-based cyber tabletop exercise conducted at the VA medical center.

· Denial-of-service attacks – MITRE reviewed VA documentation on denial-of-service protections and interviewed VA officials responsible for managing network security.

· Insider threats – MITRE drew conclusions from analysis of VA’s insider threat program and corroborated these conclusions with evidence from the five systems assessment and emulation testing from the threat-based cyber assessment.

· Threats from foreign actors – MITRE drew conclusions from the threat-based cyber assessment of the information security program, particularly findings resulting from testing networks through the emulation of specific threat actors. MITRE also corroborated these conclusions with evidence from the system assessments.

· Phishing – MITRE evaluated VA’s anti-phishing program through observation and interviews.

· Credential theft – MITRE assessed the ability of the five systems to enforce protections for user credentials and access authorizations. MITRE also drew conclusions from adversary emulation exercises associated with the threat-based cyber assessment.

· Supply chain cyber-attacks – MITRE evaluated VA’s supply chain risk management process and reviewed 20 contracts for 14 vendors across six programs.

· Remote access and telework threats – MITRE evaluated VA’s remote and telework program and the tools used to implement the program and conducted interviews with officials associated with the program.

· Other cyber threats – MITRE analyzed VA’s ability to protect against other cyber threats resulting from the 111 adversary tactics, techniques, and procedures MITRE executed during adversary emulation exercises associated with the threat-based cyber assessment.

VA’s Remediation Plan Generally Met the Act’s Requirements

VA submitted a remediation plan to Congress as required by the SVAC Act of 2022. The plan generally met the requirements of the act. Specifically, VA included a cost estimate and timelines for implementing the plan to remediate the system and program findings. While VA’s plan did not identify security control-related improvements pertaining to the five high-impact systems, the department provided us with additional documents that identified those improvements. The plan appropriately addressed improvements to the information security program.

VA’s Plan Included a Cost Estimate and Timelines for Implementation

In accordance with the act, VA included a cost estimate in its remediation plan. VA’s OIT projected a cost estimate of $60.8 million to remediate findings for the five systems and the information security program. According to agency officials, to generate this cost estimate, subject matter experts in VA’s OIT analyzed MITRE’s assessment findings and worked across VA organizations to review current capabilities and efforts to determine resource shortfalls and mitigation strategies.

As required by the act, the plan also included timelines for remediating findings from the assessment of the five systems and information security program. As previously mentioned, the cybersecurity evaluation of the five high-impact information systems identified 442 findings. VA’s remediation plan included estimated remediation dates encompassing all findings for each of the five systems. Table 3 summarizes these dates.

Table 3: High-Impact Information System Findings and Remediation Dates per Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) October 2024 Remediation Plan

|

High-impact information systema |

Number of findings |

Estimated remediation date |

|

System 1 |

107 |

12/31/2025 |

|

System 2 |

65 |

01/02/2028 |

|

System 3 |

107 |

03/30/2025 |

|

System 4 |

56 |

01/31/2025 |

|

System 5 |

107 |

12/31/2024 |

Source: GAO analysis based on VA remediation plan. | GAO‑26‑107980

aSystem names are not used due to the sensitivity of the systems.

The assessment also resulted in 11 finding areas related to the information security program. The plan included estimated remediation dates associated with remediation actions for 10 of the 11 finding areas. Table 4 includes the latest estimated remediation date associated with remediation actions for each of these finding areas, as of October 2024:

Table 4: Finding Areas and Remediation Dates for the Information Security Program per Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) October 2024 Remediation Plan

|

Finding area |

Estimated remediation date |

|

1. Customer Service to System Teams |

Not applicable* |

|

2. Cybersecurity Governance |

12/31/2025* |

|

3. Cybersecurity Risk Management |

9/30/2026 |

|

4. Information System Security Officer and System Steward Roles |

3/30/2026 |

|

5. Information Security Continuous Monitoring |

9/30/2026 |

|

6. Medical Devices |

9/30/2025 |

|

7. Cloud Security |

9/30/2025 |

|

8. Shadow IT |

2/28/2026 |

|

9. Cyber Protection |

6/30/2025 |

|

10. Cyber Detection |

9/30/2025 |

|

11. Cyber Response and Recovery |

9/30/2025 |

*Indicates that VA did not concur with these finding areas. Nonetheless, VA’s plan reported completed efforts for Customer Service to System Teams and ongoing efforts to address Cybersecurity Governance and provided a target remediation date for these ongoing efforts.

Source: GAO analysis based on VA remediation plan. | GAO‑26‑107980

VA’s Plan Generally Addressed Improvements to Security Controls and Its Information Security Program

The act required the plan to include improvements to security controls for the five high-impact systems. However, VA’s remediation plan did not include improvements to security controls associated with the 442 findings for the five systems. Instead, the plan provided an update on how many findings had been remediated for each system as of October 2024 and stated that the remediation of the remaining findings will reduce risk and heighten the security posture of the systems.

Although VA did not discuss improvements to security controls for the five systems in the plan, VA officials provided improvement details separately, which involve remediation efforts to address system findings. These efforts are covered in more detail in the following section of this report.

Further, VA’s remediation plan included planned improvements to the information security program in accordance with the act. According to MITRE, the 11 finding areas revealed challenges in the department’s information security program that hindered its ability to ensure confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information systems and to protect against the cybersecurity threats listed in the act. According to the plan, VA concurred with nine of the 11 finding areas, but did not concur with two: (1) customer service to system teams and (2) cybersecurity governance. Although VA did not concur with these two areas, the plan included completed actions and ongoing efforts, respectively, to address them, as noted in table 4.

According to VA’s remediation plan, the program finding areas identified by MITRE aligned with previous audit findings; therefore, the department was already working on improvements in these areas. The improvements in the remediation plan to address MITRE’s findings for the information security program included efforts related to advancing risk management activities; automating significant portions of documentation; improving their cyber workforce; and continuously developing and delivering trainings; among other things.

VA Reported Making Progress on Remediation Efforts for Assessment Findings

VA reported making progress on remediating MITRE’s findings for the five high-impact systems and information security program. Specifically, according to the department, it made significant progress in remediating the system findings. Further, VA reported completing several remediation actions to address the program findings, but some actions have experienced delays.

VA Reported Making Significant Progress Remediating Findings for the Five Systems

Since VA provided its remediation plan to Congress in October 2024, VA reported taking significant actions to remediate the findings for the five high-impact systems. As previously mentioned, MITRE identified 442 findings across the five system assessments.[30] These findings involved 29 high-risk, 155 moderate-risk, and 258 low-risk vulnerabilities.

According to VA’s remediation plan, as of October 2024, the department had remediated 215 of the 442 findings. In MITRE’s assessment report, it stated that the department reported remediating 14 of the 29 high-risk vulnerabilities (approximately 48 percent). As of July 2025, the department reported remediating 379 of the 442 findings. With respect to high-risk vulnerabilities, VA reported that it had remediated 27 of the 29 vulnerabilities (approximately 93 percent). Table 5 provides more details on VA’s reported remediation progress by system and risk level.

Table 5: Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Reported Remediation Progress to Address High-Impact System Assessment Findings as of July 2025

|

System |

Remediated high-risk vulnerabilities |

Remediated moderate-risk vulnerabilities |

Remediated low-risk vulnerabilities |

Total remediated vulnerabilities |

|

System 1 |

7 of 8 |

36 of 39 |

53 of 60 |

96 of 107 (90%) |

|

System 2 |

3 of 3 |

13 of 22 |

17 of 40 |

33 of 65 (51%) |

|

System 3 |

10 of 10 |

34 of 34 |

63 of 63 |

107 of 107 (100%) |

|

System 4 |

6 of 7 |

17 of 23 |

24 of 26 |

47 of 56 (84%) |

|

System 5 |

1 of 1 |

35 of 37 |

60 of 69 |

96 of 107 (90%) |

Source: GAO analysis based on VA reported remediation progress. | GAO‑26‑107980

VA Reported Completing Remediation Actions for Program Findings, but Some Actions Have Been Delayed

According to VA, the department made progress on the 11

program findings. Specifically, as of July 2025, VA reported completing 20 of

55 remediation actions across the 11 findings. For the other 35 remediation

actions, VA reported the status of these actions and estimated remediation

dates for them, as shown in table 6.

Table 6: Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Reported Remediation Progress to Address Information Security Program Assessment Findings as of July 2025

|

Finding area |

Completed remediation actions |

Estimated remediation date |

|

1. Customer Service to System Teams |

4 of 4 |

Not applicable |

|

2. Cybersecurity Governance |

3 of 7 |

12/31/2025* |

|

3. Cybersecurity Risk Management |

1 of 5 |

9/30/2026 |

|

4. Information System Security Officer and System Steward Roles |

1 of 3 |

3/30/2026 |

|

5. Information Security Continuous Monitoring |

1 of 4 |

9/30/2026 |

|

6. Medical Devices |

3 of 6 |

May 2027 |

|

7. Cloud Security |

2 of 6 |

9/30/2025* |

|

8. Shadow IT |

1 of 4 |

2/28/2026 |

|

9. Cyber Protection |

1 of 7 |

Fiscal year 2026 |

|

10. Cyber Detection |

1 of 5 |

9/30/2026 |

|

11. Cyber Response and Recovery |

2 of 4 |

Fiscal year 2026 |

*Indicates VA reported estimated remediation date as of October 2024 instead of July 2025.

Source: GAO analysis based on VA reported remediation progress. | GAO‑26‑107980

However, the department’s ongoing remediation actions for three of the nine findings have experienced delays. Specifically, according to VA, the estimated remediation dates for actions pertaining to the medical devices, cyber protection, and cyber response and recovery finding areas have experienced delays due to pending modernization efforts and staff cuts, as well as awaiting decisions on alternatives, among other things. Based on the delays, the department estimated it will complete the last of its remediation actions by May 2027.

VA’s Remediation Efforts Generally Adhered to Federal Requirements

VA’s efforts to remediate findings for the five high-impact systems and information security program generally adhered to federal requirements. The department documented planned remediation actions for the system findings according to federal requirements, but did not initially do so within its policy time frames for some findings. In addition, VA did not always update estimated remediation dates for system findings. Similarly, the department documented remediation actions addressing the program findings according to federal requirements, but did not update some estimated remediation dates.

VA Documented Efforts to Remediate Remaining System Findings, but Did Not Update Its Plans

According to NIST requirements, agencies are to remediate vulnerabilities in accordance with organization-defined response times and should develop a plan of action and milestones for a system to document the planned remediation actions to correct weaknesses noted during an assessment of controls.[31] Additionally, NIST defines a plan of action and milestones as a document that identifies tasks needing to be accomplished to resolve a deficiency.

In addition, VA policy defines time frames for the remediation of identified vulnerabilities based on the assigned level of risk.[32] Specifically, according to VA policy, high-risk vulnerabilities are expected to have remediations applied and tested within 60 days. Moderate-risk vulnerabilities are expected to be remediated within 90 days, and low-risk vulnerability time frames are determined by the system owner. Further, VA policy states that if a flaw or vulnerability cannot be remediated within the appropriate time frame, an approved plan of action and milestones must be documented, which includes an estimated remediation date.

Initially, VA did not consistently document planned remediation for some high-risk and moderate-risk vulnerabilities in accordance with its own time frames. For example, as of March 2025, over 1 year after MITRE reported the vulnerabilities to VA, the department had not yet remediated or documented plans of action and milestones for seven high-risk or moderate-risk vulnerabilities. As of July 2025, it has either remediated these vulnerabilities or documented plans of action and milestones.

However, VA did not always update remediation dates in its plans of action and milestones. For example, as of March 2025, the estimated remediation date for one high-risk vulnerability that had not yet been remediated was past due by 15 months.

Further, although plans were in place, VA’s remediation efforts were not always timely. Specifically, as of July 2025, the department had not remediated two high-risk vulnerabilities—those with the most severe consequences—over a 17-to-21-month period. MITRE provided its findings for these two systems in January 2024 and September 2023 respectively.

According to agency officials, some vulnerabilities were not remediated in a timely manner due to funding availability, staff availability, and a system migration, among other things. VA officials also explained that the challenges in documenting plans of action and milestones resulted from the department consolidating roles and reorganizing responsibilities due to staff cuts.

VA’s OIG has previously made two recommendations to VA to (1) ensure the department tracks and updates planned remediation documents and (2) improve the process for resolving vulnerabilities that cannot be addressed within policy time frames by ensuring implementation of mitigating controls.[33] However, as of July 2025, the department has not yet implemented these recommendations. By implementing the VA OIG’s recommendations, VA will have greater assurance that it is taking the necessary actions to protect its systems.

VA Documented Remediations for Program Findings, but Did Not Update Its Plans

NIST requires organizations to document and maintain plans of action and milestones for security programs. Such plans resulting from control assessments should include remediation actions and timelines to address organization-wide objectives.

VA documented remediation actions and timelines for 10 of the 11 information security program findings, according to NIST requirements. For the other finding, according to VA’s remediation plan, the department had already completed remediation actions. However, as of July 2025, VA had not updated estimated remediation dates for two of the 10 findings. Specifically, for these two findings, the estimated remediation date had passed for three remediation actions, but the department had not updated them.

As discussed above, VA’s OIG has previously made a recommendation to VA to ensure the department tracks and updates planned remediation documents. However, as of July 2025, the department has not yet implemented the recommendation. By implementing the VA OIG’s recommendation, VA can more effectively track remediation actions that will improve its information security program.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Veterans Affairs for review and comment. The department did not have any comments on the report.

We are sending copies of this report to the Senate and House Committees on Veterans’ Affairs; the Secretary of Veterans Affairs; the Veterans Affairs Office of Inspector General; and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at FranksJ@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in Appendix I.

Jennifer R. Franks

Director, Center for Enhanced Cybersecurity

Information Technology and Cybersecurity

GAO Contact

Jennifer R. Franks, franksj@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the individual named above, the following staff made key contributions to this report: Jeffrey Knott (Assistant Director), Chris Businsky, Jillian Clouse, Stephen Duraiswamy (Analyst in Charge), Samuel Giacinto, Evan Nelson Senie, Whitney Starr, and Walter Vance.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]We highlighted VA’s IT issues in our 2015 high-risk report and subsequent high-risk reports. See GAO, High-Risk Series: An Update, GAO‑15‑290 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 11, 2015); High-Risk Series: Progress on Many High-Risk Areas, While Substantial Efforts Needed on Others, GAO‑17‑317 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 15, 2017); High-Risk Series: Substantial Efforts Needed to Achieve Greater Progress on High-Risk Areas, GAO‑19‑157SP (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 6, 2019); High-Risk Series: Dedicated Leadership Needed to Address Limited Progress in Most High-Risk Areas, GAO‑21‑119SP (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 2, 2021); High-Risk Series: Efforts Made to Achieve Progress Need to Be Maintained and Expanded to Fully Address All Areas, GAO‑23‑106203 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2023); and High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025).

[2]Strengthening VA Cybersecurity Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-302, 136 Stat. 4384. (Dec. 27, 2022).

[3]According to NIST, high-impact systems are those systems where the loss of confidentiality, integrity, or availability of the systems or the information they contain can have a severe or catastrophic adverse effect on an organization’s operations, assets, or individuals. Adverse effects can include loss or degradation of mission capability, severe harm to individuals, or major financial loss.

[4]Though the act required MITRE to review VA’s information security management system in addition to the information security program, this report will only refer to the information security program. MITRE reviewed the information security management system as part of its assessment of the information security program.

[5]National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), The NIST Cybersecurity Framework, Version 2.0 (Gaithersburg, MD: Feb. 26, 2024).

[6]According to the act, shadow IT is the use of information technology systems, devices, and services by employees and contractors of the department without the heads of the elements of the department that are responsible for information technology knowing or approving such use.

[7]National Institute of Standards and Technology, Assessing Security and Privacy Controls in Information Systems and Organizations, Special Publication 800-53A, Revision 5 (Gaithersburg, MD: January 2022).

[8]National Institute of Standards and Technology, Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations, Special Publication 800-53, Revision 5 (Gaithersburg, MD: September 2020).

[9]Department of Veterans Affairs, Enterprise Vulnerability Management Solutions, Vulnerability Management for Department of Veterans Affairs Information Systems, (Oct. 1, 2022).

[10]VA policy does not require specific remediation timelines for low-risk vulnerabilities. System owners determine remediation timelines for low-risk vulnerabilities.

[11]The Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 (FISMA 2014), Pub. L. No. 113-283, 128 Stat. 3073 (2014) (44 U.S.C. §§ 3551-3558) largely superseded the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA 2002), Pub. L. No. 107-347, Title III, 116 Stat. 2899, 2946 (2022). As used in this report, FISMA refers both to FISMA 2014 and those provisions of FISMA 2002 that were either incorporated into FISMA 2014 or were unchanged and continue in full force and effect. This act provides a comprehensive framework for ensuring the effectiveness of information security controls over federal agency operations and assets.

[12]National Institute of Standards and Technology, Security and Privacy Controls.

[13]National Institute of Standards and Technology, Assessing Security and Privacy Controls.

[14]Exec. Order No. 13800, Strengthening the Cybersecurity of Federal Networks and Critical Infrastructure, 82 Fed. Reg. 22391 (May 16, 2017).

[15]National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), The NIST Cybersecurity Framework, Version 2.0 (Gaithersburg, MD: Feb. 26, 2024).

[16]GAO, Cybersecurity: VA Needs to Address Privacy and Security Challenges, GAO‑23‑106412 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 18, 2023).

[17]GAO, Cybersecurity: Agencies Need to Fully Establish Risk Management Programs and Address Challenges, GAO‑19‑384 (Washington, D.C.: July 25, 2019).

[18]MITRE, VA Information Security Program Assessment Report (McLean, VA: Apr. 30, 2024).

[19]Department of Veterans Affairs, Information Security Program Remediation Plan (October 2024).

[20]MITRE, Testimony of David Powner Before the Subcommittee on Technology Modernization of the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee, (Nov. 20, 2024).

[21]MITRE’s assessment of the five high-impact systems resulted in 11 recommendations.

[22]Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Inspector General, Statement of Michael Bowman Director of the Information Technology Security Division for the Office of Audits and Evaluations, Nov. 20, 2024. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Inspector General, Federal Information Security Modernization Act Audit for Fiscal Year 2023, Audit 23-01105-69, (Washington, D.C.: May 14, 2024).

[23]VA, Statement of Kurt Delbene Assistant Secretary for Information and Technology and Chief Information Officer, Nov. 20, 2024.

[24]A zero trust architecture is a set of cybersecurity principles stating that organizations must verify everything that attempts to access their systems and services.

[25]Strengthening VA Cybersecurity Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-302, §2,136 Stat. 4384, 4385. (Dec. 27, 2022).

[26]According to MITRE, VA computes information system risk scores using a quantitative formula that incorporates security criteria from VA’s Authority to Operate Scorecard.

[27]Committee on National Security Systems, Security Categorization and Control Selection for National Security Systems, Instruction No. 1253. (Mar. 27, 2014). The instruction requires at least one of the three security objectives (confidentiality, integrity, and availability) for a system to be classified as high for the system to be considered high impact.

[28]National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Cybersecurity Framework.

[29]MITRE Corporation, MITRE ATT&CK®, version 17.1, (Apr. 22, 2025), https://attack.mitre.org. MITRE’s ATT&CK framework is a knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques used as a basis for organizations to develop threat models and methodologies.

[30]VA received individual system reports from MITRE for each of the five systems over the course of 6 months, spanning from September 2023 to February 2024.

[31]National Institute of Standards and Technology, Security and Privacy Controls.

[32]Department of Veterans Affairs, Vulnerability Management.

[33]The VA Office of Inspector General made these recommendations in at least its last two reports for its FISMA audits. See Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Inspector General, Federal Information Security Modernization Act Audit for Fiscal Year 2023, Audit 23-01105-69, (Washington, D.C.: May 14, 2024) and Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Inspector General, Federal Information Security Modernization Act Audit for Fiscal Year 2024, Audit 24-01233-90, (Washington, D.C.: June 18, 2025).