TERRORIST WATCHLIST

FBI Should Improve Outreach Efforts to Nonfederal Users

Report to Congressional Requesters

GAO-26-108650

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Tina Won Sherman at shermant@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

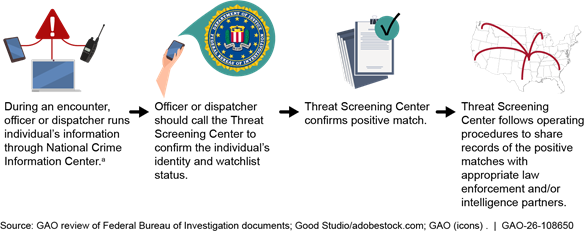

Nonfederal law enforcement officers query encountered individuals against the terrorist watchlist during routine police interactions, such as traffic stops. After encountering a potentially terrorist watchlisted individual, nonfederal law enforcement officers receive instructions, via the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), to contact the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Threat Screening Center to determine whether the individual is a positive or negative match to the terrorist watchlist.

GAO found that almost half of the law enforcement entities GAO interviewed in four states (12 of 26 entities, including police and sheriff’s departments) reported that officers were not consistently reporting encounters with potentially terrorist watchlisted individuals in instances where it is warranted. Seeking information to understand the extent to which nonfederal law enforcement entities are consistently reporting terrorist watchlist encounters could improve the accuracy of watchlist records.

aDispatchers may be used by police departments to query the National Crime Information Center instead of the responding officer.

The Threat Screening Center uses outreach efforts to communicate terrorist watchlisting policies to nonfederal law enforcement entities that use the terrorist watchlist. However, GAO found that FBI has not ensured nonfederal law enforcement entities are aware of terrorist watchlist policies and has not taken steps to develop a communication plan for its outreach efforts. Developing a communication plan with goals and measures as well as periodic assessments of progress would help accomplish this. Additionally, FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services does not ensure states train NCIC users on terrorist watchlist policies. Without developing a process to review states’ efforts to do so, FBI cannot ensure that state training programs instruct nonfederal law enforcement to properly protect and respond to terrorist watchlist information.

Why GAO Did This Study

The Threat Screening Center, administered by FBI, is responsible for managing the terrorist watchlist. In recent years, Members of Congress have raised questions about how nonfederal entities use the terrorist watchlist.

GAO was asked to examine the use of the terrorist watchlist by nonfederal law enforcement entities. This report examines (1) nonfederal entities’ reporting of terrorist watchlist encounters to FBI and opportunities for improvement and (2) steps FBI has taken to ensure nonfederal entities’ awareness of watchlist policies through outreach and state-led trainings.

GAO reviewed watchlist policies and training resources for nonfederal entities and collected encounter data for fiscal years 2019 through 2024. GAO interviewed nonfederal law enforcement officials in four states selected based on the number of encounters and other factors. While not generalizable, these interviews provided insights into officials’ awareness of policies and training.

This is the public version of a sensitive report GAO issued in August 2025. Information on encounter data and official FBI instructions on handling watchlist encounters that FBI deemed sensitive has been omitted.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that FBI (1) seek information to understand the extent to which nonfederal law enforcement entities are consistently reporting terrorist watchlist encounters, (2) develop a communication plan to improve its outreach efforts, and (3) develop a process to review state efforts to instruct NCIC users about watchlist policies. FBI concurred with the recommendations.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CJIS |

Criminal Justice Information Services |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FBI |

Federal Bureau of Investigation |

|

NCIC |

National Crime Information Center |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 12, 2026

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Seth Magaziner

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Counterterrorism and Intelligence

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

Terrorism remains a persistent threat to the United States. The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Threat Screening Center is responsible for managing the Terrorist Screening Dataset, commonly referred to as the terrorist watchlist.[1] The terrorist watchlist is the federal government’s primary method to consolidate and share information about individuals who may pose terrorist threats to the United States.

Federal agencies provide access to relevant subsets of the terrorist watchlist or share watchlist information with nonfederal law enforcement entities, which are responsible for enforcing laws, maintaining public order, and managing public safety in a nonfederal capacity. These entities include state, tribal, county, and local or municipal police, as well as fusion centers.[2] They screen individuals against watchlist information for homeland security, law enforcement, and other authorized functions.

In recent years, Members of Congress and advocacy groups have raised questions about how nonfederal entities use the terrorist watchlist to screen individuals for a variety of purposes, including for employment, travel, and benefits, and as part of routine traffic interactions.

We have reported on a variety of terrorist watchlist-related topics since the Threat Screening Center was created in 2003, including the criteria used to nominate individuals to the watchlist and government actions to improve watchlisting and screening processes.[3]

You requested that we examine the use of the terrorist watchlist by nonfederal law enforcement entities. This report addresses:

1. What data show about nonfederal law enforcement entities’ encounters with terrorist watchlisted individuals, and opportunities to improve reporting of these encounters to FBI; and

2. Steps FBI has taken to ensure nonfederal law enforcement entities are aware of terrorist watchlist policies through outreach efforts and state-led training.

This report is based on publicly releasable information from a sensitive report we issued in August 2025.[4] FBI deemed some information sensitive and in need of protection from public disclosure. Consequently, we omitted the following types of information from this report:

· The section on nonfederal law enforcement entities’ encounters with terrorist watchlisted individuals omits information on the positive watchlist encounters (those that the Threat Screening Center confirm as a match to the terrorist watchlist) by nonfederal law enforcement entities, according to FBI data from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2024. Such information includes the number of encounters by fiscal year, by citizenship status, and by state, and the recorded basis for inclusion on the terrorist watchlist. This section also omits examples of automated responses that nonfederal law enforcement officers would receive for a potentially terrorist-watchlisted individual.

· The section on FBI’s steps to ensure awareness of terrorist watchlist policies omits an image of a Threat Screening Center reference document that the Center provides to nonfederal law enforcement entities. This section also omits some examples of the specific terrorist watchlist-related use parameters FBI provides to nonfederal law enforcement.

· The report omits an appendix containing data on nonfederal law enforcement agencies with terrorist watchlist encounters from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2024. The data include the 10 nonfederal law enforcement agencies that had the most positive terrorist and non-terrorism-related watchlist encounters and the number of nonfederal entities within each state that had at least one encounter that the Threat Screening Center deemed a match with a watchlisted individual.

Although the information provided in this report is more limited, it generally addresses the same objectives and uses the same methodology as the sensitive report.

To address both of our objectives, we spoke with officials representing 55 different nonfederal law enforcement entities during 26 interviews. These entities included fusion centers, state police departments, and local police departments and sheriff’s offices. We conducted the interviews both in person and virtually with entities based in the four states we selected for having relatively high levels of reported terrorist watchlist encounters, among other factors: California, Michigan, Texas, and Virginia. The entities also included officials from four national law enforcement associations, many of whom also served in a leadership role within their law enforcement entity.[5]

To examine what the data show about nonfederal law enforcement entities’ encounters with terrorist watchlisted individuals, we analyzed Threat Screening Center record-level data on the results of encounters determined to be positive matches to the watchlist from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2024. We assessed the reliability of the data by reviewing data documentation; interviewing knowledgeable officials; and conducting electronic testing to identify missing values, outliers, or other obvious errors. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of reporting the characteristics of those individuals who were positive matches to the terrorist watchlist.

To evaluate the extent to which opportunities exist to improve reporting of nonfederal encounters with individuals on the terrorist watchlist, we compared FBI’s Threat Screening Center’s data collection practices against its responsibilities outlined in Homeland Security Presidential Directive-6 and a related memorandum.[6] These responsibilities include ensuring that watchlist records are current and accurate and ensuring, consistent with applicable law, that appropriate information possessed by nonfederal law enforcement entities, which is available to the federal government, is considered in making Center determinations.

To evaluate the extent to which FBI ensures nonfederal law enforcement entities are aware of terrorist watchlist policies through outreach, we reviewed documents that guide outreach on the watchlist. This included training and reference materials provided by the Threat Screening Center to local law enforcement entities and schedules of the Threat Screening Center’s past outreach events with nonfederal law enforcement entities from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2024. We also reviewed a video produced by the Threat Screening Center to train law enforcement on how to manage a watchlist encounter.

We evaluated FBI’s outreach efforts to determine whether they addressed FBI’s responsibilities as outlined in Homeland Security Presidential Directive-6 and a related memorandum.[7] FBI’s responsibilities include making watchlist information accessible to state, local, tribal, and territorial authorities to support their screening processes and otherwise enable them to identify or assist in identifying watchlisted individuals.

To evaluate the extent to which FBI ensures nonfederal law enforcement entities are aware of terrorist watchlist policies through training, we reviewed FBI policy documents and agreements that facilitate nonfederal law enforcement entities’ access to the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database. Such documents included NCIC policies, operating manuals, and the user agreements between FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) and state organizations managing the NCIC data in the four states we selected. These documents outline CJIS’s responsibilities for ensuring states are training users to appropriately use the system, including terrorist watchlist data. We evaluated CJIS’s review of state NCIC training programs to determine how it ensures compliance with applicable terrorist watchlist policies (such as those included in the NCIC operating manual).[8]

For additional information on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We worked with FBI and DHS from July 2025 to January 2026 to prepare this public version of the original sensitive report.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to August 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of the Threat Screening Center and Terrorist Watchlist

Threat Screening Center

The Threat Screening Center is a multi-agency center administered by FBI with detailees from other federal departments and agencies, including the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Pursuant to Homeland Security Presidential Directive-6 and built upon through Homeland Security Presidential Directives 11 and 24, the Threat Screening Center was established to manage the terrorist watchlist and shares information for security-related and other screening processes.[9]

Terrorist Watchlist

The terrorist watchlist is an unclassified dataset derived from a classified database containing biographic (e.g., first name, last name, and date of birth) and biometric (e.g., photographs, iris scans, and fingerprints) identifying information about individuals with a nexus to terrorism. Identity information maintained in the terrorist watchlist is considered Law Enforcement Sensitive/Sensitive Security Information and is for screening purposes only. The terrorist watchlist generally receives information from two sources: the National Counterterrorism Center’s Terrorist Identities Datamart Environment and FBI’s Sentinel Database. As appropriate, FBI and DHS share terrorist watchlist records with federal, state, local, tribal, territorial, and foreign governments with arrangements to share terrorist screening information for their respective screening and vetting processes.

The nomination process for including individuals on the terrorist watchlist is based on an assessment of available intelligence and investigative information against applicable standards. The standard for inclusion on the terrorist watchlist is generally one of reasonable suspicion. To meet the reasonable suspicion standard for inclusion on the terrorist watchlist as a known or suspected terrorist, the nominator must rely upon articulable intelligence or information which, based on the totality of the circumstances, creates a reasonable suspicion that the individual is engaged, has been engaged, or intends to engage in conduct constituting, in preparation for, or in aid or in furtherance of terrorism and/or terrorist activities. Nominations to the terrorist watchlist are made based on information from:

· law enforcement,

· homeland security and intelligence communities,

· U.S. embassies and consulates abroad, and

· foreign partners with which the federal government has international agreements to share terrorist screening information.

Before an individual is added to the terrorist watchlist, the nomination undergoes a multi-step review process at the nominating agency, at the National Counterterrorism Center or FBI (as appropriate), and then again at the Threat Screening Center to ensure compliance with interagency standards for inclusion. For individuals to be included on the watchlist as a known or suspected terrorist, the nomination must include enough identifying information to allow analysts at the Threat Screening Center to be able to determine whether the individual they are screening is a match to a record on the terrorist watchlist and to establish a reasonable suspicion that the individual is a known or suspected terrorist. We have previously reviewed the nomination process in a sensitive report published in March 2025.[10]

Law Enforcement Encounters

An encounter is an event in which an individual is identified during a screening process to be a potential match to an individual who is on the terrorist watchlist. An encounter can be an in-person interaction (e.g., inspection at a U.S. port of entry, visa interview, or traffic stop), electronic (e.g., Electronic System for Travel Authorization application or a visa application), or paper-based (e.g., review of visa petition). When an encounter occurs, the agency or the encountering officer contacts the Threat Screening Center to confirm whether the individual matches the record on the terrorist watchlist. If the individual is confirmed to match the identity contained in the Threat Screening Center’s terrorist watchlist record, each encountering agency is to take appropriate action according to internal policies as well as regulatory and statutory standards applicable to that agency’s mission.[11]

A watchlisting advisory committee, co-chaired by the Threat Screening Center and the National Counterterrorism Center and composed of federal agencies, publishes interagency watchlisting guidance to help nominating and encountering agencies understand terrorist watchlist policies. The guidance, last updated in 2023, articulates minimum derogatory standards and sufficient identifying information for determining an individual’s eligibility for presence on the watchlist. It also provides specific criteria needed to ensure proper identification during screening. The guidance does not specifically apply to nonfederal law enforcement entities accessing the watchlist.

FBI’s National Crime Information Center Database

Nonfederal law enforcement entities, such as state and local law enforcement, may have access to certain terrorist watchlist information through the National Crime Information Center (NCIC). NCIC is a system operated by FBI’s CJIS, which provides criminal justice information to federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial agencies. NCIC was established in 1967 to assist law enforcement agencies in apprehending fugitives and locating stolen property.[12]

Nonfederal law enforcement entities can query encountered individuals through their state NCIC system. Each state has a designated “CJIS Systems Agency,” which we refer to as a state systems agency. These agencies integrate the NCIC system into their various state systems and share responsibility with FBI for monitoring compliance with NCIC use requirements. Each state systems agency generally operates its own computer systems, determines which agencies within its jurisdiction may access and enter information into NCIC, and is responsible for ensuring law enforcement agency adherence to operating procedures within its jurisdiction. Each state systems agency is responsible for administering and overseeing users of NCIC in its jurisdiction, including training and auditing all NCIC users in its jurisdiction. FBI is responsible for ensuring the appropriate use of NCIC, including by conducting triennial audits of each state’s NCIC operations.

Fusion Centers

Fusion centers are state-owned and operated centers that serve as focal points in states and major urban areas for the receipt, analysis, gathering, and sharing of threat-related information—including terrorist watchlist information provided to the Homeland Security Information Network through the DHS Watchlist Service—among federal, nonfederal, and private sector entities.[13] DHS created the Homeland Security Information Network as an online portal to share sensitive but unclassified information between federal, state, local, tribal, territorial, international, and private sector partners. The DHS Watchlist Service maintains a synchronized copy of the terrorist watchlist, which disseminates watchlist records it receives to authorized DHS components, including through the Homeland Security Information Network. DHS Intelligence Officers from DHS’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis are often embedded in fusion centers to help facilitate the sharing of threat-related information. DHS Intelligence Officers assist fusion centers and nonfederal partners in sharing and analyzing intelligence to develop a comprehensive threat picture, as well as provide guidance in the production and dissemination of intelligence and information products to nonfederal entities.

Additionally, DHS maintains the Homeland Security Information Network as the primary means for disseminating both raw and finished intelligence reporting, including information from the terrorist watchlist to fusion centers, private sector security officials, and other federal, state, and local partners such as FBI. For additional information on the role of fusion centers in the terrorist watchlist encounter process, see appendix II.

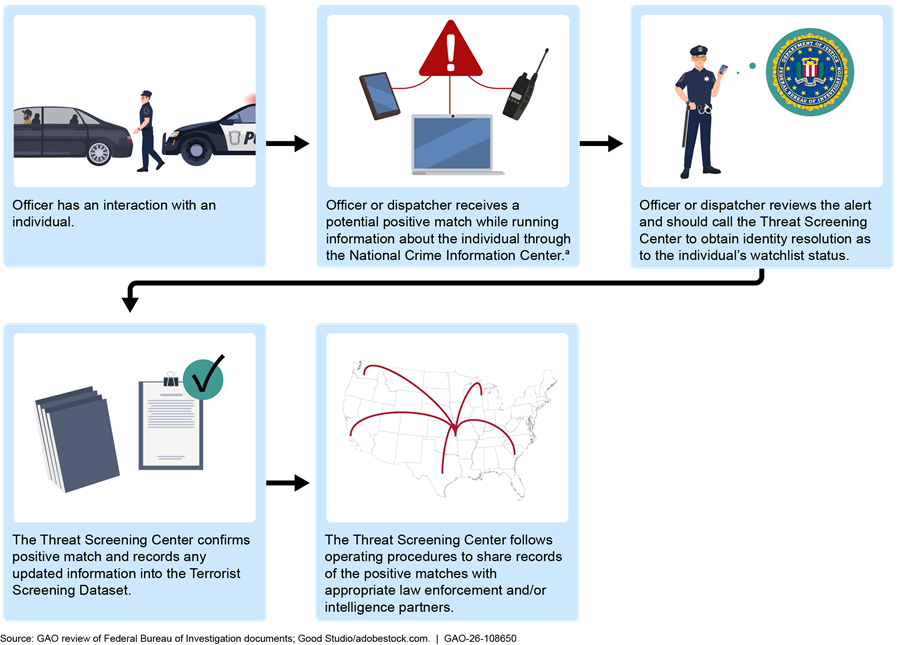

Nonfederal Law Enforcement Process for Querying the Terrorist Watchlist

Nonfederal law enforcement officers query encountered individuals against the terrorist watchlist in NCIC during routine police interactions. During a traffic stop, for example, the law enforcement officer or dispatcher will query the state NCIC platform to determine if the encountered individual matches against NCIC files, including the terrorist watchlist. If the information queried is a potential match to an individual on the terrorist watchlist, the law enforcement officer will receive an alert.

The alert identifies that an individual is a potential match to the terrorist watchlist and advises the nonfederal law enforcement officer to contact the Threat Screening Center. The alert also advises the officer not to inform the individual about potential placement on the terrorist watchlist.

If the individual encountered is a potential match to an individual on the terrorist watchlist, the law enforcement officer is advised to contact FBI’s Threat Screening Center using a toll-free telephone number. When a Threat Screening Center analyst receives the phone call from the law enforcement officer, the analyst will gather information about the encountered individual. The Threat Screening Center will attempt to make a determination about the identification of the individual, including whether the individual is a positive or negative match to the terrorist watchlist.

The Threat Screening Center analyst may also request additional information from the law enforcement officer. Law enforcement officials cited vehicle description as an example of such requests.[14] The analyst may also conduct additional analyses using available databases. Figure 1 depicts how a nonfederal law enforcement officer may respond to an encounter with an individual on the terrorist watchlist.

aDispatchers may be used by police departments to query the National Crime Information Center instead of the responding officer. Officers we spoke to stated that this may be the case in rural areas where computers are not available in police cars or when an officer does not have a car, such as when they are on a motorcycle.

In addition to the terrorist watchlist, nonfederal law enforcement entities may be alerted to an encountered individual’s potential match on other government watchlists through NCIC queries. For example, in 2015, the Threat Screening Center began developing the Transnational Organized Crime Actor Detection Program. As part of this program, the Threat Screening Center stood up a new watchlist—the transnational organized crime watchlist—specifically for maintaining and sharing information on transnational organized crime actors and transnational criminal organizations. Similar to terrorist watchlist information, some transnational organized crime watchlist information is exported to NCIC. For the purposes of this report, our evaluation focuses on the nonfederal use of the terrorist watchlist only.

Nonfederal Entities Reported Terrorist Watchlist Encounters in All 50 States, but Encounter Data May Not Be Complete

Positive Terrorist Watchlist Encounters Were Reported by 2,198 Nonfederal Law Enforcement Entities from Fiscal Year 2019 Through Fiscal Year 2024

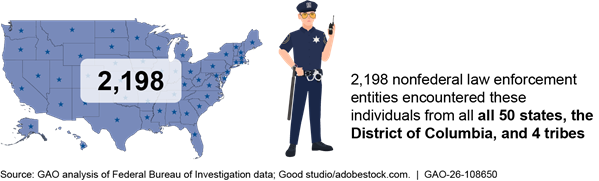

Terrorist watchlist encounters were reported by 2,198 nonfederal law enforcement entities (and confirmed as positive matches by the Threat Screening Center) in all 50 states plus the District of Columbia and four tribal law enforcement agencies, based on our analysis of FBI data from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2024, as shown in figure 2.[15]

Figure 2: Positive Terrorist Watchlist Encounters by Nonfederal Law Enforcement Entities, Fiscal Years 2019 Through 2024

Note: Our sensitive report provided additional summary data on the positive terrorist watchlist encounters during this time period, including the number of encounters by fiscal year, the number of encounters by citizenship status, and the most frequent reasons individuals were on the watchlist. This information is omitted here because it is sensitive.

Approximately 5 percent of positive terrorist watchlist encounters occurred at the nonfederal level during the time period we reviewed. Our sensitive report provided additional information on the number of positive watchlist encounters during this time period. For example, the report describes the distribution of encounters by state and the recorded basis for inclusion of reported terrorist watchlist encounters by nonfederal law enforcement entities. Those statements are omitted here because they are sensitive information.

FBI May Have Incomplete Terrorist Watchlist Encounter Data and Other Information

After encountering a potentially terrorist-watchlisted individual, nonfederal law enforcement officers receive instructions, via NCIC, to contact the Threat Screening Center.[16] However, according to Threat Screening Center officials, the instructions in the NCIC automated message do not require nonfederal law enforcement officers to notify FBI of potential watchlist encounters. Rather, officers are advised to call, and according to Threat Screening Center officials, the decision to report the encounter is left to the officer’s discretion.

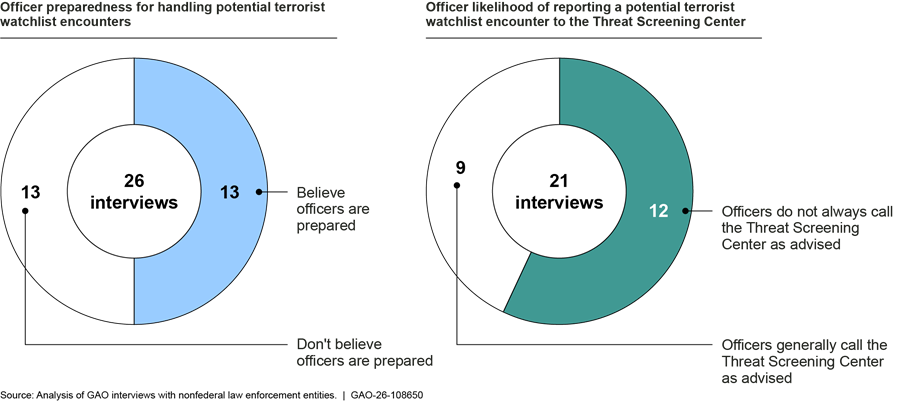

For example, if an officer makes their own determination that the encountered individual does not match the individual referred to in the NCIC automated response message, the officer may decide not to report the encounter to the Threat Screening Center. According to Threat Screening Center officials, having nonfederal law enforcement entities report every potential terrorist-watchlist match in NCIC—including those that officers determine are not a positive match—would overload the call center, making it difficult to respond to positive watchlist matches in a timely manner. While the Threat Screening Center requests that nonfederal law enforcement officers report encounters where there is a possibility of a positive match with the terrorist watchlist, the extent to which nonfederal law enforcement officers are adhering to the request in the NCIC automated response message is unknown.

In our interviews with nonfederal law enforcement entities in four states, officials in half (13 of 26) of our interviews indicated that they do not believe that all of their officers are prepared to handle a terrorist watchlist encounter.[17] Further, officials in 12 of 26 of our interviews told us that their officers do not always call the Threat Screening Center as advised. Specifically, they believed that law enforcement officers in their areas of responsibility were not consistently reporting encounters with potential terrorist-watchlisted individuals to the Threat Screening Center in instances where it was warranted. Officials in nine of 26 of our interviews told us that they believed that their law enforcement officers were reporting encounters with watchlisted individuals to the Threat Screening Center, as shown in figure 3.[18]

Figure 3: Nonfederal Law Enforcement Entities’ Responses to GAO Interview Questions About Officer Handling of Potential Terrorist Watchlist Encounters

Note: We conducted 26 interviews with officials representing 55 nonfederal law enforcement entities. We excluded interviews where officer handling of potential terrorist watchlist encounters was not discussed, or if officials could not speak to the topic.

During these interviews, officials cited several reasons why an officer may not report the encounter to the Threat Screening Center. These include a lack of familiarity with the terrorist watchlist’s purpose or FBI’s expectations, being overwhelmed with other tasks, and failure to see the instructions included in the NCIC watchlist notification. Officials in five of 26 of our interviews with nonfederal law enforcement entities stated that the instructions provided in the NCIC automated response message were adequate for officers, while in seven of 26 of our interviews officials stated more information would be helpful.[19] Additionally, in six of 26 interviews, nonfederal law enforcement officials told us that the terrorist watchlist information in NCIC is sometimes challenging to identify. They explained that the NCIC return could be “buried” because there is frequently a significant amount of other information that appears on their screen, unrelated to the watchlist.[20]

Law enforcement officials in more than two thirds of our interviews (18 of 26) said that they would like to receive feedback from the Threat Screening Center on their entity’s handling of terrorist watchlist encounters, including the extent to which their entity is reporting encounters. Threat Screening Center officials told us that, in the past, representatives from the Threat Screening Center have spoken at law enforcement conferences and other gatherings about how contacting the Center aids in investigations and other instances of identity resolution for watchlist encounters, such as confirming whether the individual encountered is on the terrorist watchlist. These officials described their efforts as “moderately successful,” but noted that additional resources would be required to conduct more outreach.

However, the Threat Screening Center does not know the extent to which nonfederal law enforcement entities (or their officers) are consistently reporting potential terrorist watchlist encounters as advised in the NCIC automated message, due in part to technical limitations. According to Threat Screening Center officials, the Center previously operated a unit that used NCIC data to periodically sample a number of potential terrorist watchlist encounter alerts that were received by nonfederal law enforcement entities. Officials said that on a limited, ad hoc basis, officials were able to match records of those alerts with corresponding phone calls from nonfederal law enforcement entities to report the encounters. This allowed the Threat Screening Center to better understand how many potential terrorist watchlist encounters were not reported by nonfederal law enforcement entities.

Threat Screening Center officials said that the unit would then contact the nonfederal law enforcement entities whose officers had not called the Threat Screening Center as advised. Officials would provide feedback that included why it is important to call the Threat Screening Center. The unit would also provide positive feedback for officers who appropriately contacted the Threat Screening Center.

According to Threat Screening Center officials, the unit responsible for these activities ceased operations approximately five years ago. Officials cited resource constraints as one of the reasons that these operations ceased. However, officials could not provide additional details or documentation due to the length of time that had elapsed and because they were not aware of any staff with additional knowledge about the prior unit. Additionally, officials were not able to provide any technical details of the prior program and noted that it may not be technically feasible or cost or time effective to replicate the prior matching effort on a global scale due to the large volume of encounters. While matching efforts may not be feasible at this scale, there may be other steps that the Threat Screening Center could take to obtain a better understanding of the extent to which nonfederal law enforcement entities are reporting encounters to them. This would help the Center identify any potential gaps in its reporting program and focus on supporting those nonfederal law enforcement entities.

Under Homeland Security Presidential Directive-6 and a related memorandum, the Threat Screening Center is responsible for ensuring that watchlist records are current and accurate and ensuring, consistent with applicable law, that appropriate information possessed by nonfederal law enforcement entities, which is available to the federal government, is considered in making Center determinations. Interagency watchlisting guidance indicates that the Threat Screening Center confirms whether an individual identified during the screening process is a positive match to the terrorist watchlist and notifies appropriate law enforcement stakeholders of the encounter, providing any intelligence collected during the event. These determinations are critical for maintaining current and accurate records of encounters with watchlisted individuals to support intelligence analysis and investigations.

However, as we learned during our interviews with officials from nonfederal law enforcement entities, officers may not have seen the instructions in the NCIC automated message or may not have been familiar with the purpose of the watchlist and therefore may not consistently and appropriately report encounters. Without consistent reporting of encounters with these individuals, the Threat Screening Center’s records may not be current and accurate and therefore may limit the usefulness of terrorist watchlist information for investigations.

By better understanding the extent to which nonfederal law enforcement entities are consistently reporting encounters with potentially watchlisted individuals, the Threat Screening Center would help ensure that its watchlist records are current and accurate. For example, the Threat Screening Center could seek more recent information on nonfederal law enforcement’s terrorist watchlist reporting practices by reaching out to selected entities that received terrorist watchlist alerts through NCIC, or may seek such information during outreach events where nonfederal law enforcement entities are present. Doing so could result in the Threat Screening Center obtaining additional information about why these entities may not be reporting encounters and take steps to identify and address those reasons, as appropriate.

FBI Has Not Ensured Nonfederal Law Enforcement Awareness of and Training on Terrorist Watchlist Policies

FBI Has Not Ensured that Nonfederal Law Enforcement Entities Are Aware of Terrorist Watchlist Policies

FBI’s Threat Screening Center uses outreach efforts to raise awareness of applicable terrorist watchlist policies to nonfederal law enforcement officials who use the terrorist watchlist. These efforts include in-person and virtual activities, such as presentations at conferences and working groups where nonfederal law enforcement officials are present, as well as visits to individual law enforcement departments. During these activities, officials from the Threat Screening Center provide an overview of its functions and the purpose of the terrorist watchlist, procedures for managing watchlist encounters, and information about the proper handling of watchlist information.

The Threat Screening Center’s outreach efforts also include providing officials at nonfederal law enforcement entities with supplemental reference materials to assist in managing watchlist encounters. For example, the Threat Screening Center produced a brief video demonstrating a law enforcement officer’s encounter with an individual whose NCIC query returned a potential terrorist watchlist match, explaining appropriate actions and procedures. The Threat Screening Center also developed a one-page reference document explaining the handling codes that could be included in a watchlist encounter, and what actions law enforcement officials are expected to take for each handling code.[21] Our sensitive report provided an image of this reference document. The image is omitted here because it is sensitive information.

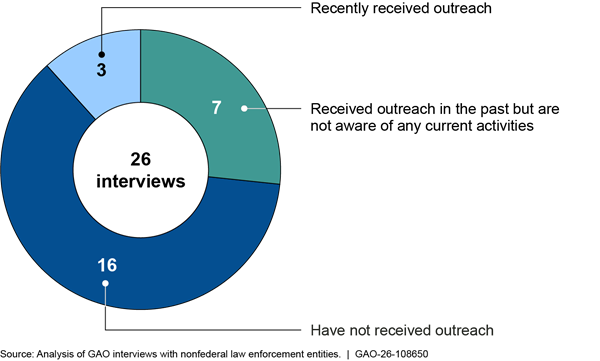

Although these outreach activities reached some nonfederal law enforcement entities, FBI has not ensured that nonfederal law enforcement entities are aware of applicable terrorist watchlist policies. For example, in most of the interviews with officials from nonfederal law enforcement entities (23 of 26), officials said that they were not familiar with any in-person or virtual Threat Screening Center outreach activities or they have received this type of outreach in the past but were not aware of any current activities, as shown in figure 4.[22]

Figure 4: Nonfederal Law Enforcement Entities’ Responses to GAO Interview Questions About Familiarity with Threat Screening Center Outreach Activities

Note: We conducted 26 interviews with officials representing 55 nonfederal law enforcement entities.

Further, the frequency with which the Threat Screening Center conducted in-person or virtual outreach activities between fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2024 was inconsistent. Table 1 summarizes the number of in-person or virtual outreach events involving nonfederal law enforcement entities by fiscal year and by the type of group participating in outreach.

Table 1: Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Threat Screening Center In-Person or Virtual Outreach Events for Nonfederal Law Enforcement by Participant Group as Reported by FBI Officials, Fiscal Year 2019 through Fiscal Year 2024

|

Fiscal year |

State or local law enforcement agency |

Fusion center |

Association, group, or training center |

Professional event (e.g., conference) |

Total |

|

2019 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

2020 |

1 |

11 |

0 |

1 |

13 |

|

2021a |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

2022 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

|

2023 |

3b |

1 |

7 |

1 |

12 |

|

2024 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

9 |

|

Total |

4 |

15 |

13 |

9 |

43 |

Source: GAO analysis of FBI’s Threat Screening Center documentation. | GAO‑26‑108650

aAccording to Threat Screening Center officials, the Center did not conduct in-person or virtual outreach events in fiscal year 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

bThreat Screening Center officials reported that in fiscal year 2023, they also conducted direct outreach to a state and local law enforcement agency for case-specific information sharing purposes.

According to Threat Screening Center officials, raising awareness about applicable terrorist watchlisting policies with nonfederal law enforcement entities is a high priority, but the Center has limited resources to do so. They noted that they are looking into other ways to support nonfederal law enforcement entities given resource limitations and are willing to provide in-person or virtual outreach or training to nonfederal law enforcement entities upon request.

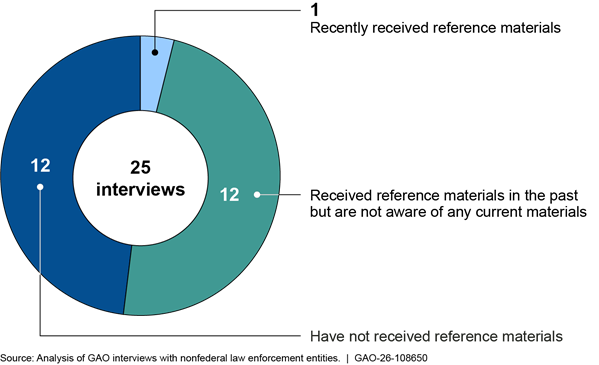

In addition to in-person and virtual events, the Threat Screening Center’s outreach efforts include disseminating reference materials to nonfederal law enforcement entities, such as its reference document on handling codes. However, most of the nonfederal law enforcement officials we interviewed were not aware of these materials or how to access them. Officials in most of our nonfederal law enforcement interviews (24 of 26) said that they had not received any terrorist watchlist-related reference materials from the Threat Screening Center or received them in the past but were not aware of any current materials, as shown in figure 5.[23]

Figure 5: Nonfederal Law Enforcement Entities’ Responses to GAO Interview Questions About Familiarity with Threat Screening Center Reference Materials

Note: We conducted 26 interviews with officials representing 55 nonfederal law enforcement entities. We excluded interviews where officer handling of terrorist watchlist encounters was not discussed.

For example, nonfederal law enforcement officials in one interview said that they received the Threat Screening Center’s reference document on handling codes a long time ago, but that they no longer distribute this resource to the law enforcement entities in their area of responsibility because they were not sure if the document was up-to-date.

According to Threat Screening Center officials, the Center does not have a system or process for distributing terrorist watchlist reference materials to nonfederal law enforcement entities. Officials said that the reference materials are distributed to nonfederal law enforcement on an ad hoc basis (such as providing them during a Threat Screening Center training event or upon request), and are also available on FBI’s Law Enforcement Enterprise Portal, which is a secure platform for state and local law enforcement entities as well as intelligence groups and criminal justice entities.

However, many nonfederal law enforcement officials we interviewed were not aware of the availability of these reference materials. Specifically, in most of our interviews (23 of 26), law enforcement officials expressed an interest in receiving additional reference materials from the Threat Screening Center, and nearly one half (11 of 23) of those expressing interest noted that a brief video or one-page reference document would be an ideal resource for their officers. These two types of materials are available on FBI’s portal; however, the officials were not aware of this. In addition, Threat Screening Center officials said they do not track the extent to which nonfederal law enforcement officials are accessing this information through their portal.

We also found that nonfederal law enforcement entities in rural areas may need more information on the terrorist watchlist. Officials in all five of our interviews with rural law enforcement entities said that they were not familiar with any Threat Screening Center in-person or virtual outreach efforts and did not know of any current watchlist-related reference materials from the Center. Officials in most of these interviews (four of five) said that they faced more challenges in managing watchlist encounters than their counterparts in more urban areas, such as staffing and technology limitations, less coordination with federal law enforcement agencies, and less exposure to watchlist issues.

Nonfederal law enforcement entities that are unfamiliar with the Threat Screening Center’s outreach efforts may be at an increased risk of instances where their officers overreact to a watchlist encounter (such as improperly arresting a watchlisted individual) or underreact (such as overlooking the encounter or not reporting it to the Threat Screening Center). As noted in figure 3, officials in half (13 of 26) of the interviews indicated that they do not believe that all of their law enforcement officers are prepared to handle a terrorist watchlist encounter. Additionally, in nearly half (12 of 26) of the interviews, nonfederal law enforcement officials noted that due to high turnover and a newer workforce, their officers may not have a full understanding of the purpose and use of the terrorist watchlist.[24]

Homeland Security Presidential Directive-6 established the Threat Screening Center to consolidate the government’s approach to terrorism screening and provide for the appropriate and lawful use of terrorist information in screening processes. This includes providing nonfederal law enforcement entities with appropriate information that enables them to identify or assist in identifying watchlisted individuals, and ensuring that terrorist watchlist activities are carried out in a manner consistent with the Constitution and applicable laws.[25] Further, federal internal control standards state that agencies should set clear goals, including defining what is to be achieved and how it will be achieved, to ensure compliance with applicable policies and procedures. Agencies should define those goals in measurable terms so that performance towards achieving those goals can be assessed periodically.[26]

While according to officials, the Threat Screening Center has conducted outreach to guide its nonfederal partners on terrorist watchlist use and is working on new ways to do so, the Center does not have a communication plan with clearly defined and measurable goals. Such a plan could help the Threat Screening Center gain insight into the effectiveness of its outreach efforts, use its limited resources more efficiently, and help maximize the number of nonfederal law enforcement officials who are informed of applicable terrorist watchlist policies and available resources. In addition, implementing a periodic assessment of FBI’s progress towards meeting those goals would help ensure that nonfederal law enforcement entities have the information and resources needed to continuously update officers on these policies.[27] This plan could also incorporate FBI’s efforts to better understand nonfederal law enforcement entities’ terrorist watchlist reporting, which could also contribute to the currency and accuracy of watchlist records, as discussed earlier in this report.

FBI Does Not Ensure NCIC Users’ Awareness of Terrorist Watchlist Policies Through State-Led Training

To access NCIC, state systems agencies must sign a user agreement with FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS). Under those agreements, CJIS and state systems agencies share the responsibility of ensuring appropriate use of NCIC and both parties are responsible for ensuring the protection of criminal justice information, including information related to the terrorist watchlist. State systems agencies are responsible for training NCIC users in its jurisdiction on applicable FBI policies and regulations. CJIS responsibilities include ensuring the training is conducted in accordance with its policies through a variety of ways, such as by developing minimum training requirements and monitoring the training programs of state systems agencies.[28]

As part of their user agreement with CJIS, state systems agencies must ensure that their NCIC users adhere to the NCIC operating manual, which includes a chapter on the terrorist watchlist. This chapter includes: background on how terrorist watchlist records are entered and updated in NCIC, information on understanding an NCIC terrorist watchlist notification, an overview of handling codes, and requirements for managing a terrorist watchlist encounter. While CJIS has processes to review the efforts of state systems agencies in instructing NCIC users on a range of topics, these topics are not required to include the handling of terrorist watchlist information. As a result, FBI does not know if NCIC users are aware of how to handle such information. Examples of such processes are:

· Minimum training requirements. CJIS requires state systems agencies to develop NCIC training programs that satisfy minimum requirements.[29] For example, the NCIC operating manual requires state systems agencies to ensure that law enforcement personnel are trained on NCIC within 12 months of employment and to annually review all training curricula administered within the state for relevancy and effectiveness.[30] However, while NCIC policy includes topics that organizations should include in their training programs, CJIS does not require state NCIC training programs to include terrorist watchlist information or requirements, or to provide training on how to manage a terrorist watchlist encounter.[31]

According to FBI officials, FBI does not have a role in developing or implementing state training content or training requirements, other than setting the minimum requirements. They also noted that state systems agencies may have more stringent policies and procedures. NCIC policy also outlines that state systems agencies are responsible for ensuring an annual review of all NCIC training content within the state. CJIS ensures that they are doing so as a part of its triennial audit (discussed below).

· Triennial audits. NCIC policy requires that CJIS conduct a triennial audit of nonfederal NCIC users in each state to assess compliance with applicable statutes, regulations, and policies. The audit includes an examination of state systems agency training programs.[32] For example, CJIS examines each state systems agency’s initial training and testing, maintenance of training records, and reviews of training content.

According to CJIS officials, CJIS provides a brief overview of terrorist watchlist information to nonfederal NCIC users during its triennial audit. However, the agency does not check for the inclusion of terrorist watchlist-related training as a part of this audit. Officials said that the audit includes a site visit component where they briefly instruct state systems agencies and selected nonfederal law enforcement entities on the appropriate handling of NCIC-provided terrorist watchlist information. Officials noted that the overview is limited, and covers topics related to protecting watchlist information and contacting the Threat Screening Center when an officer receives a watchlist notification. This overview is offered to officials who implement and oversee the use of NCIC in each state, as well as to NCIC coordinators and leadership in selected nonfederal law enforcement entities, but not directly to nonfederal law enforcement officers who would use NCIC during a possible terrorist watchlist encounter. According to officials, CJIS does not ensure that states include the terrorist watchlist information from its overview in officer trainings and does not know the extent to which state systems agencies have shared that information with its NCIC users.

· Training assistance and NCIC-related reference materials. NCIC policy as well as CJIS user agreements with state systems agencies indicate that CJIS is responsible for providing training assistance and NCIC-related materials to its authorized users, including state systems agencies. As mentioned above, CJIS provides some information to state systems agencies on developing an NCIC training curriculum, but this does not include information on the terrorist watchlist.

The extent to which FBI provides support, materials, or feedback to state systems agencies on trainings that are specifically related to the terrorist watchlist is unclear. CJIS officials said they evaluate specific training curricula—including training related to the terrorist watchlist—on an as-needed basis, only at the request of the state systems agency. However, CJIS officials were unable to provide examples of specific training feedback they have provided to state systems agencies. Officials said that they maintain documentation of NCIC training assistance by retaining training attendance rosters only, and do not collect or maintain training materials from state systems agencies.

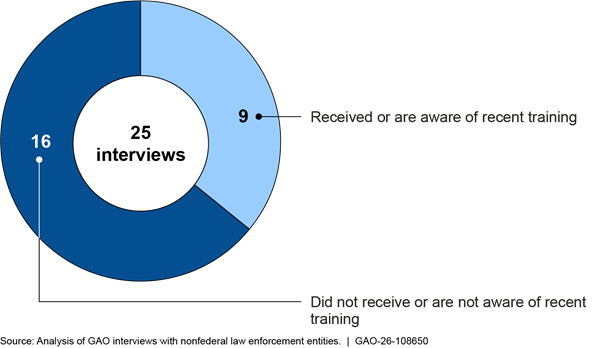

Our analysis of interviews with nonfederal law enforcement officials suggests that the inclusion of terrorist watchlist information in state and local NCIC training curricula varies, as shown in figure 6 below.

Figure 6: Nonfederal Law Enforcement Entities’ Responses to GAO Interview Questions About Familiarity with State or Local Training Related to the Terrorist Watchlist

Note: We conducted 26 interviews with officials representing 55 nonfederal law enforcement entities. We excluded interviews where officer handling of terrorist watchlist encounters was not discussed.

For example, in over half of the interviews (16 of 26), nonfederal law enforcement officials indicated that they did not receive or did not know about any currently available training on the terrorist watchlist, including state or local training. In about one-third of the interviews (9 of 26), at least one nonfederal law enforcement official indicated that they are aware of training on the terrorist watchlist provided through their state, fusion center, or local law enforcement leadership.[33] We do not know the extent to which this variability exists across all states. However, our findings raise questions about FBI’s ability to ensure that NCIC users are aware of requirements related to the terrorist watchlist.[34]

The NCIC system makes terrorist watchlist information immediately available to nonfederal law enforcement agencies with the purpose of enhancing officer and public safety. According to the NCIC operating manual, the success of the system depends on the extent to which its users—including nonfederal law enforcement officers—use it in compliance with FBI policies and instructions. The operating manual also states that to preserve the integrity of the data in the system, the standards and procedures outlined in the manual must be strictly followed.

Federal internal control standards call for agencies to hold service organizations (such as state systems agencies) accountable for their assigned control activities (such as ensuring compliance with the watchlist instructions outlined in the NCIC operating manual) and to communicate its expectations to these organizations.[35] While FBI ensures some accountability for state systems agencies through CJIS review processes of state systems agency training efforts (establishing minimum training requirements, conducting triennial audits, and providing training assistance), these processes do not necessarily incorporate terrorist watchlist information. Consequently, FBI cannot ensure that state training programs are increasing awareness of NCIC users—including nonfederal law enforcement officers—on policies related to the terrorist watchlist (such as those outlined in the NCIC operating manual) to properly protect terrorist watchlist information in NCIC and to respond to terrorist watchlist encounters.

Developing and implementing a process to review the efforts of state systems agencies in instructing NCIC users on the handling of terrorist watchlist information would provide better assurance that nonfederal law enforcement personnel are aware of how to handle terrorist watchlist information. This, in turn, could help those personnel better protect that information and properly manage terrorist watchlist encounters.

Conclusions

According to FBI, information obtained from law enforcement entities during a terrorist watchlist encounter is used to update watchlist records and provides valuable intelligence that directly affects national security. To that end, FBI’s Threat Screening Center advises nonfederal law enforcement entities to report terrorist watchlist encounters to it, but does not know of instances where watchlist encounters are not currently being reported. Consequently, FBI may be missing opportunities to update and share critical information gathered from those encounters with its national security and counterterrorism stakeholders.

Having a better understanding of the extent to which nonfederal law enforcement entities are consistently reporting terrorist watchlist encounters to the Threat Screening Center, and subsequently taking steps to identify and address the reasons encounters are not consistently reported, will help the Threat Screening Center maintain more current and accurate records of watchlisted individuals. These records can then be used to support future encounters and investigations. Additionally, doing so can help the Center provide targeted and specific feedback to nonfederal law enforcement entities on how they use watchlist information.

While terrorist watchlist encounters are low-frequency events for individual nonfederal law enforcement entities, their high-risk nature makes it critical for FBI to provide those entities with the appropriate information for their preparedness in managing such encounters. Insufficient preparedness may impact the quality of information sharing efforts between FBI and nonfederal law enforcement entities and may also impact the extent that officers from these entities manage watchlist encounters consistent with FBI policies. However, it is not clear that nonfederal law enforcement entities consistently receive watchlist information through the Threat Screening Center’s outreach efforts, or through CJIS’s training requirements and monitoring of state-provided NCIC training. A communication plan with clearly defined and measurable goals could help the FBI better understand the extent that nonfederal law enforcement officers are aware of applicable terrorist watchlist policies, and to use its limited resources more efficiently as it continues its outreach efforts. Further, a process to review the efforts of state systems agencies in instructing NCIC users on applicable terrorist watchlist policies could help ensure that all NCIC users—including nonfederal law enforcement entities—have received a baseline of critical information on the terrorist watchlist. Without such efforts, FBI cannot ensure that nonfederal law enforcement—often the first line of defense in ensuring national security—are sufficiently prepared.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making three recommendations to FBI:

The Director of FBI should ensure that the Threat Screening Center seeks information to better understand the extent to which nonfederal law enforcement entities are consistently reporting terrorist watchlist encounters and takes steps to identify and address the reasons, as appropriate, that officers may not report a terrorist watchlist encounter. (Recommendation 1)

The Director of FBI should develop and implement a communication plan with clear, measurable goals and periodic assessments of progress to increase nonfederal law enforcement entities’ awareness of terrorist watchlist policies. (Recommendation 2)

The Director of FBI should develop and implement a process to review the efforts of state systems agencies in instructing NCIC users on how to handle terrorist watchlist information, such as through its training requirements, audits, or training assistance efforts. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of the sensitive report to DHS and DOJ for review and comment. Both agencies provided technical comments on the draft which we reviewed and incorporated as appropriate. Neither agency provided formal written comments; however, FBI provided comments orally and in email, which are summarized below. FBI subsequently stated in an email that it concurred with each of our three recommendations.

FBI senior Threat Screening Center officials provided comments orally and in email that raised concerns with the feasibility of implementing an aspect of recommendation one as it was written in our draft report. Specifically, the email stated that comprehensively determining the extent to which nonfederal law enforcement entities are consistently reporting terrorist watchlist encounters would not be possible due to the large volume of data that would be technically difficult and resource intensive to obtain. The email requested that our recommendation not require the Threat Screening Center to determine the full extent to which nonfederal law enforcement is reporting terrorist watchlist encounters given these concerns.

As such, we added examples to clarify how the Threat Screening Center could collect this information, to include interviews, surveys, or performing encounter-related data matching of a sample of law enforcement entities from certain geographic locations, demographic distributions, or job descriptions. Once collected, the Threat Screening Center should analyze the results of its selected method to better understand whether those law enforcement entities were properly reporting its encounters to the Center. The Threat Screening Center should then identify and implement any steps that may improve the consistency of reporting practices among nonfederal law enforcement entities.

Finally, we modified the language of this recommendation to make clear that the Threat Screening Center should seek information that would help it to better understand the extent to which nonfederal law enforcement is reporting encounters rather than determining the full extent of encounters not reported. FBI concurred with the recommendation, as revised.

We are providing copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Attorney General, the Secretary of Homeland Security, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at shermant@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Tina Won Sherman

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

We were asked to examine the use of the terrorist watchlist by nonfederal law enforcement entities. This report addresses (1) what data show about nonfederal law enforcement entities’ encounters with terrorist watchlisted individuals, and opportunities to improve reporting of these encounters to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and (2) the steps FBI has taken to ensure nonfederal law enforcement entities are aware of terrorist watchlist policies through outreach efforts and state-led training.

This report is based on publicly releasable information from a sensitive report we issued in August 2025.[36] FBI deemed some information sensitive and in need of protection from public disclosure. Consequently, we omitted the following types of information from this report:

· The section on nonfederal law enforcement entities’ encounters with terrorist watchlisted individuals omits information on the positive watchlist encounters (those that the Threat Screening Center confirm as a match to the terrorist watchlist) by nonfederal law enforcement entities, according to FBI data from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2024. Such information includes the number of encounters by fiscal year, by citizenship status, and by state, and the recorded basis for inclusion on the terrorist watchlist. This section also omits examples of automated responses that nonfederal law enforcement officers would receive for a potentially terrorist-watchlisted individual.

· The section on FBI’s steps to ensure awareness of terrorist watchlist policies omits an image of a Threat Screening Center reference document that the Center provides to nonfederal law enforcement entities. This section also omits some examples of the specific terrorist watchlist-related use parameters FBI provides to nonfederal law enforcement.

· The report omits an appendix containing data on nonfederal law enforcement agencies with terrorist watchlist encounters from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2024. The data include the 10 nonfederal law enforcement agencies that had the most positive terrorist and non-terrorism-related watchlist encounters and the number of nonfederal entities within each state that had at least one encounter that the Threat Screening Center deemed a match with a watchlisted individual.

Although the information provided in this report is more limited, it generally addresses the same objectives and uses the same methodology as the sensitive report.

To address both objectives, we spoke with officials representing 55 different nonfederal law enforcement entities during 26 in-person or virtual interviews. These entities included fusion centers, state police departments, and local police departments and sheriff’s offices. The entities were based in four states selected for site visits: California, Michigan, Texas, and Virginia.

To identify and select states and urban areas where law enforcement officials would be more likely to have experience identifying potential watchlist matches and managing encounters with watchlisted individuals, we reviewed data about which states had relatively high levels of confirmed terrorist watchlist encounters. We also consulted with groups and associations that have experience in using the watchlist. Specifically, we consulted with representatives from national law enforcement associations to identify urban areas that have had success or challenges in using the watchlist.

For each urban area, we interviewed a nongeneralizable sample of three to four state or local law enforcement officials, such as those from state police departments, sheriff’s offices, and local police departments. We also interviewed officials from one rural law enforcement entity near each of the four urban areas.[37]

We also met with officials located at fusion centers—state-owned and operated centers that serve as focal points in states and major urban areas for the receipt, analysis, gathering, and sharing of threat-related information.[38] We met with federal, state, and local law enforcement officials as available at each fusion center to learn about any policies and procedures for watchlist use, what officials see when state and local law enforcement entities identify a match during screening (i.e., how a potential match appears on the fusion center’s computer screen); how the fusion center coordinates between federal, state, and local officials during watchlist encounters; and any other watchlist-based services or products fusion centers may produce.

We used these interviews to gather information and observe how terrorist watchlist screening, vetting, and encounter guidance is implemented at the state and local levels, and any reported challenges faced by law enforcement officials in implementing watchlist policies. During one of these interviews, we also observed what officials see when a match is found during screening (i.e., how a potential match notification appears on the law enforcement officer’s computer screen). In addition, because dispatchers are sometimes involved in the process of handling terrorist watchlist queries for state and local law enforcement officers, we interviewed dispatcher associations in each state to better understand the processes that dispatchers follow and the training that dispatchers receive.

The interviewed entities also included officials from four national law enforcement associations, many of whose officials also served in a leadership role within their law enforcement entity. We also interviewed representatives from the National Emergency Number Association, representing the perspectives of dispatchers. Some of these association officials represented law enforcement entities in locations outside of our four selected states. We use the “interview” as the unit of analysis because many of the organizations we met with were represented by individuals who spoke to various perspectives in the same interview. For example, during one fusion center interview, leadership of the fusion center were also employees of the local police department and spoke to their perspective representing both entity types.

To examine what the data show about nonfederal law enforcement entities’ encounters with terrorist watchlisted individuals, we analyzed Threat Screening Center record-level data on the results of encounters determined to be positive matches to the terrorist watchlist from fiscal years 2019 through 2024. We assessed the reliability of the data by reviewing data documentation; interviewing knowledgeable officials; and conducting electronic testing to identify missing values, outliers, or other obvious errors. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of reporting the characteristics of those individuals who were positive matches to the terrorist watchlist.

To evaluate the extent to which opportunities exist to improve reporting of nonfederal encounters with individuals on the terrorist watchlist, we compared FBI’s Threat Screening Center’s data collection practices against its responsibilities outlined in Homeland Security Presidential Directive-6 and a related memorandum, including to ensure that watchlist records are current and accurate and to ensure, consistent with applicable law, that appropriate information possessed by nonfederal law enforcement entities, which is available to the federal government, is considered in making Center determinations.[39]

To evaluate the extent to which FBI ensures nonfederal law enforcement entities are aware of terrorist watchlist policies through outreach, we reviewed documents that guide outreach on the watchlist. This included training and reference materials provided by the Threat Screening Center to local law enforcement entities and schedules of the Threat Screening Center’s past outreach events with nonfederal law enforcement entities from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2024. We also reviewed a video produced by the Threat Screening Center to train law enforcement on how to manage a watchlist encounter.

We evaluated FBI’s outreach efforts to determine whether they addressed FBI’s responsibilities as outlined in Homeland Security Presidential Directive-6 and a related memorandum.[40] Specifically, FBI is responsible for making watchlist information accessible to state, local, tribal, and territorial authorities to support their screening processes and otherwise enable them to identify or assist in identifying watchlisted individuals. We also evaluated these outreach efforts to determine whether they meet federal internal control standards. Specifically, principle six calls for agencies to define goals clearly, and in specific and measurable terms.[41]

To evaluate the extent to which FBI ensures nonfederal law enforcement entities are aware of terrorist watchlist policies through training, we reviewed FBI policy documents and agreements that facilitate nonfederal law enforcement entities’ access to the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database. Such documents included NCIC policies, operating manuals, and the user agreements between FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) and state organizations managing the NCIC data in the four states we selected. These documents outline CJIS’s responsibilities for ensuring states are training users to appropriately use the system, including terrorist watchlist data.

We determined that the control environment component of federal internal control standards was significant to this objective. Specifically, principle five calls for agencies to hold service organizations (such as state systems agencies) accountable for their assigned control activities (such as ensuring compliance with the watchlist instructions outlined in NCIC’s operating manual), and to communicate its expectations to these organizations.[42] We evaluated CJIS’s review of state NCIC training programs to determine how it ensures compliance with applicable terrorist watchlist policies (such as those included in the NCIC operating manual).

We worked with FBI and DHS from July 2025 to January 2026 to prepare this public version of the original sensitive report.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to August 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Appendix II: Role of Fusion Centers in the Terrorist Watchlist Encounter Process and Inputs from Fusion Center Officials

Fusion centers play a role in analyzing information related to positive terrorist watchlist encounters.[43] For example, when a confirmed positive terrorist watchlist encounter occurs after a nonfederal law enforcement officer reports the encounter to the Threat Screening Center, the Center will notify local fusion centers through the Department of Homeland Security’s Homeland Security Information Network.

The Threat Screening Center provides fusion centers with information on the date and time of the notification; encounter location; biographical information and miscellaneous identifiers of the watchlisted individual; National Crime Information Center handling code; and encounter details. According to one Homeland Security Information Network posting about a positive terrorist watchlist encounter that we reviewed, those encounter details can also include the encountering agency, the reason for the original encounter (e.g., traffic violation), the name of the watchlisted individual, vehicle information, and other biographical information.

Fusion centers may use the data they receive from the Homeland Security Information Network to query the terrorist watchlist and use the information gathered to produce analytic products. For example, officials from seven of the nine fusion centers that we interviewed said that, upon receiving a terrorist watchlist notification from the Homeland Security Information Network, they will query multiple databases to gather additional information about the watchlisted individual who was encountered. Fusion center officials told us that they often share this information with other agencies, such as DHS, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and state-level offices.[44] Further, officials from four of the nine fusion centers we spoke with said that, in addition to sharing information about the individuals, they aggregate information about the terrorist watchlist encounters to develop analytical products that provide a high-level overview of those encounters in their geographic area of responsibility. Officials from five of the nine fusion centers did not develop such analytical products.

While fusion centers often use the information to create analytical products, officials from fusion centers that we interviewed stated that they are not tracking how law enforcement officials are responding to terrorist watchlist encounters. Officials from eight of the nine fusion centers we interviewed said that they do not track how state and local law enforcement officers are responding to the encounters (such as whether they are reporting the encounters to the Threat Screening Center).[45]

GAO Contact

Tina Won Sherman, shermant@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgements

In addition to the contact named above, David Lutter (Assistant Director), Ryan Lester (Analyst in Charge for GAO‑26‑107086SU), Danielle Pakdaman (Analyst in Charge for GAO‑26‑108650), Melissa Hargy, Erin O’Brien, Mona Nichols Blake, Christopher Zubowicz, Michele Fejfar, Kevin Reeves, Sadaf Dastan, Ben Crossley, David Ballard, Derika Weddington, and Luis Rodriguez made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]For the purposes of our work, we refer to the Terrorist Screening Dataset as the terrorist watchlist, which includes exports (i.e., subsets) of the Terrorist Screening Dataset, such as the No Fly List, the Selectee List, and the Expanded Selectee List. In March 2025, the name of the Center was changed from Terrorist Screening Center to Threat Screening Center.