INFORMATION ENVIRONMENT

DOD Faces Risks with Publicly Accessible Information

Statement of Joseph W.

Kirschbaum, PhD

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

Before the Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate

For Release on Delivery Expected at 2:30 p.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

Chairwoman Ernst, Ranking Member Slotkin, and Members of the Subcommittee:

I am pleased to be here today to discuss the risks of the growing use of electronic devices and online activities by the Department of Defense’s (DOD) personnel and their operations. Throughout the day, people—including DOD service members, employees, contractors, and family members— leave behind massive amounts of traceable data that can be collected and aggregated by the public, data brokers, and malicious actors. These data, in the aggregate, can undermine national security and pose significant security, privacy, and safety risks.

All of this digital activity generates volumes of traceable information—also known as a digital footprint. Over time, multiple footprints can create a digital profile that can reveal potentially sensitive or classified information. We have previously issued reports highlighting how this escalation in volume, the interconnectedness of data, and the evolving DOD information environment have changed the landscape of information and national security.[1]

My testimony summarizes our pending report entitled Information Environment: DOD Needs to Address Security Risks of Publicly Accessible Information.[2] This statement focuses on (1) risks of publicly available data about DOD personnel and operations, and (2) DOD’s approach to address security-related risks.

In conducting our work, we developed and examined threat scenarios that depict potential consequences from the exploitation of publicly accessible digital data. We developed these scenarios based on analyses of literature research, interviews, and our own investigation. We also collected and reviewed information from officials from the Office of the Secretary of Defense and a non-generalizable sample of 10 DOD components. Our work was performed in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. We conducted our related investigative work in accordance with investigation standards prescribed by the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency. More detailed information on the scope and methodology of our work can be found in our report.

Malicious Actors’ Access to Digital Information of DOD Personnel and Operations Poses Growing Risk

DOD officials and documents identify the public accessibility of digital data as a real and growing threat that poses risks to personnel privacy and safety, mission success, and national security. To illuminate this threat, we developed notional threat scenarios that exemplify how malicious actors can collect and use digital information about DOD operations and its personnel that appears in the public domain.

· Risk to personnel and their families: Exposure of personal information such as identity, rank, unit affiliation, patterns of behavior, and family details.

· Risk to naval operations: Disclosure of real-time intelligence about a ship’s movements, personnel, and onboard conditions.

· Risk to military capabilities: Identification of vulnerabilities in military training, operations, and equipment.

· Risk to leadership: Disclosure of a military official’s behaviors and associations to predict their movements and objectives.

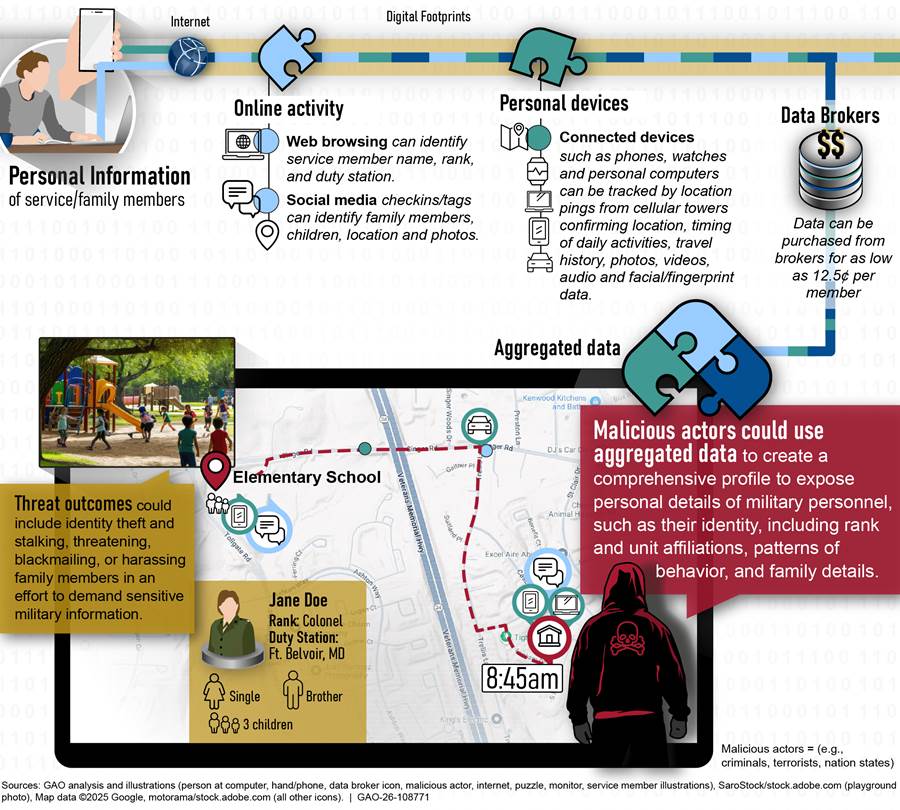

For example, figure 1 shows how digital information purchased from data brokers or collected from the web could be used to identify and harm DOD personnel and their families.

Figure 1: Scenario of Threat Outcomes from Exposure of DOD Personnel Information

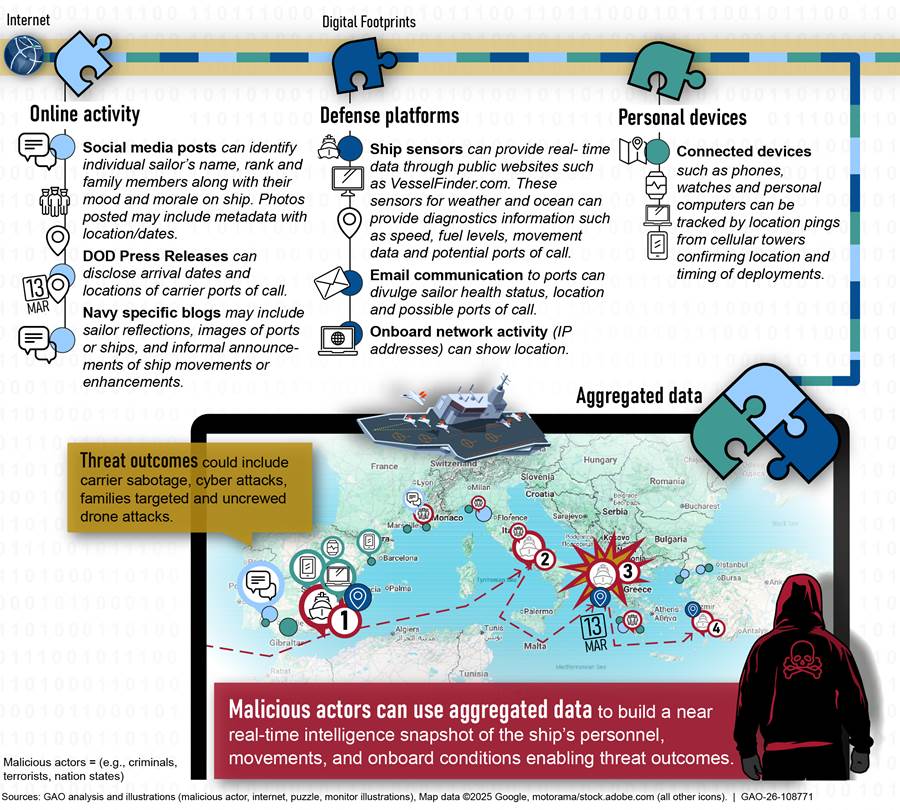

Figure 2 provides an illustration of how digital information could be used by malicious actors to potentially project the route of an aircraft carrier and disrupt naval operations. This information can be collected from sources including social media posts, DOD press releases, and blogs.

Figure 2: Scenario of Threat Outcomes from Disclosure of Naval Operations

In our review of risk to military capabilities, we note that cybersecurity researchers found forum discussions on the dark web that included advertisements for military manuals on tank operations and improvised explosive device training. Also, our investigators found a social media post with videos of military jump training, including live military flights, internal views of the aircraft, and equipment used by the paratroopers. The training manuals could be purchased from the dark web.

In our review of risk to leadership, we identified a scenario in which an Army official traveling to a high-profile military conference downloaded a video game for their child to use during their travel. However, the application had extensive access to sensitive information and functions on the official’s phone, including location, credit card, contacts, camera and microphone, SMS messages, and network access.

DOD Has an Established Approach to Manage Security-Related Risks but Needs to Take Additional Actions

DOD’s Approach to Managing Security-Related Risks

DOD has established security disciplines and related functions to manage risks. These disciplines and functions include (but are not limited to) counterintelligence, antiterrorism (force protection), insider threat, mission assurance, operations security, and critical program information protection. The advantages of having security disciplines are the department could use existing structures, doctrine, and policy to build in new considerations. Conversely, the expansive and separate nature of this structure can result in uneven progress.

|

Counterintelligence: Information gathered and activities conducted to identify, deceive, exploit, disrupt, or protect against espionage, other intelligence activities, sabotage, or assassinations conducted for or on behalf of foreign powers, organizations or persons or their agents, or international terrorist organizations or activities. Force protection: Preventive measures taken to mitigate hostile actions against Department of Defense (DOD) personnel (including family members), resources, facilities, and critical information. Insider threat: A threat presented by a person who has, or once had, authorized access to information, a facility, a network, a person, or a resource of DOD and knowingly or unknowingly commits an act in contravention of law or policy that resulted in or might result in harm through the loss or degradation of government or company information, resources, or capabilities, or a destructive act, which may include physical harm to oneself or another. Mission assurance: A process to protect or ensure the continued function and resilience of capabilities and assets, including personnel, equipment, facilities, networks, information and information systems, infrastructure, and supply chains critical to the execution of DOD mission-essential functions in any operating environment or condition. Operations security: An activity that identifies and controls critical information and indicators of friendly force actions. Critical program information protection: U.S. capability elements that contribute to the warfighters’ technical advantage, which if compromised, undermines U.S. military preeminence. U.S. capability elements may include software algorithms and specific hardware residing on the system, its training equipment, or maintenance support equipment. |

Source: GAO analysis of DOD documents. | GAO‑26‑108771

To manage security-related risks, DOD has assigned senior-level officials within the Office of the Secretary of Defense who provide policies, procedures, and guidance on how to limit the amount and type of digital information that is accessible to the public. Specifically, the

· Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security establishes and oversees the implementation of policies and procedures for security areas such as DOD counterintelligence, insider threat, operations security, and program protection.[3]

· Under Secretary of Defense for Policy establishes and oversees the implementation of policies and procedures for DOD mission assurance and antiterrorism, which includes force protection.[4]

· Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering establishes policies for development and approval of systems engineering plans and program protection plans, among other things.[5]

· Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs acts as the sole authority for releasing DOD information and visual information materials, including press releases.[6]

· DOD Chief Information Officer develops the department’s cybersecurity policy and guidance.[7]

In addition, DOD components are responsible for implementing DOD issuances to protect information, personnel, equipment, and operations.[8] Some examples:

· Military departments conduct training and assessments on operations security.

· Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency provides security training.

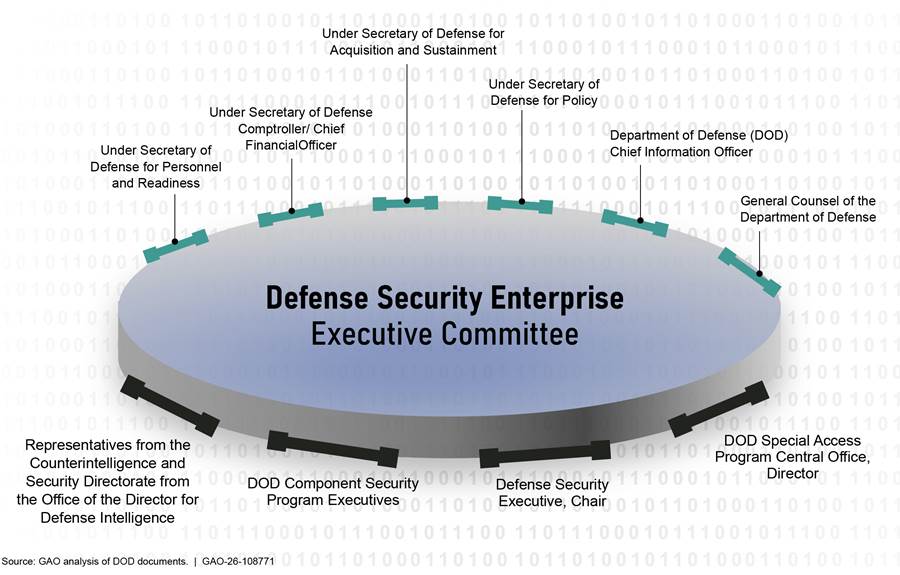

Moreover, DOD has established other organizations, such as the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee.[9] The committee includes stakeholders from across the department, as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Defense Security Enterprise with Senior-Level DOD Officials Across Security Disciplines and Functions

DOD Needs to Take Action to Reduce Risks of Publicly Accessible Digital Data

DOD has taken some actions that address risks associated with publicly available information about DOD operations and personnel. For example,

· The DOD Chief Information Officer issued a policy prohibiting military personnel, civilian employees, and contractor personnel from using personal email or other nonofficial accounts to exchange official information. [10]

· The Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs issued a policy providing core principles and guidance on social media use, along with guidance for social media records management.[11]

· The Defense Information Systems Agency has incorporated digital profile risks in the DOD-wide cybersecurity training that every employee is supposed to complete annually.

· A Joint Staff organization, known as Joint Staff Operational Security Element, hosted a week-long conference in 2025 that highlighted the OPSEC risks associated with digital profile.

Several DOD components administer training that touches upon risks associated with digital profiles. For example, the Defense Intelligence Agency’s Joint Counterintelligence Training Academy offers a course on understanding remote surveillance (also known as ubiquitous technical surveillance) and how the five pathways of collection (see text box) integrate to pose a threat to intelligence activities.

|

Ubiquitous technical surveillance is the collection and long-term storage of data in order to analyze and connect individuals with other people, activities, and organizations. Ubiquitous technical surveillance is organized into five pathways of collection: · Online (e.g., internet searches and websites) · Electronic (e.g., Bluetooth connections, GPS information, and smart devices) · Financial (e.g., banking applications and tap to pay) · Visual-physical (e.g., CCTV cameras and smart doorbell) · Travel (e.g., flight itineraries and GPS location searches) |

Source: International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development. | GAO‑26‑108771

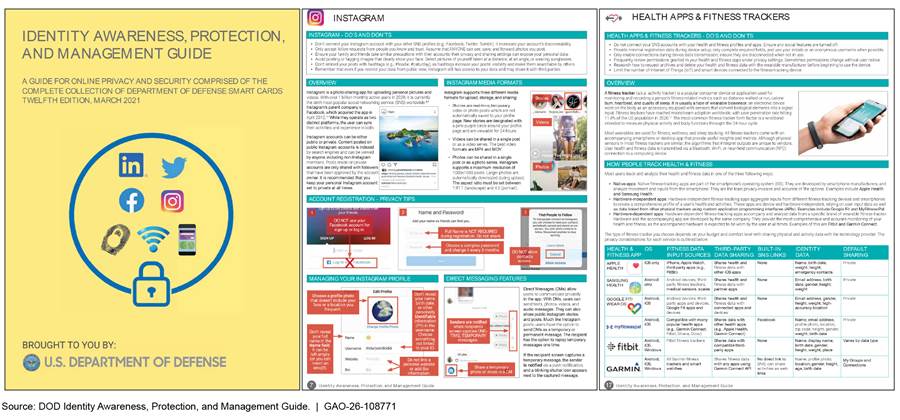

· DOD components have developed posters, smartcards, or other awareness documents to help employees understand how to keep their identities private and secure online.[12] This collection of smartcards provide an individual the tools, recommendations, and step-by-step guides for implementing settings that maximize their security in a variety of digital sources, such as Facebook, fitness trackers, online dating services, and smartphones (see figure 4).

Figure 4: Example of Department of Defense’s Smartcards on Securing Digital Profiles

However, most of DOD’s efforts to address the risks have almost exclusively been through DOD’s OPSEC program and not the other security disciplines. The scenarios discussed above highlight that public accessibility of digital information impacts multiple security disciplines—including OPSEC, counterintelligence, force protection, mission assurance, program protection. For example:

· The offices of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy (responsible for force protection and mission assurance) and the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (responsible for program protection) do not have any policies or guidance that identify actions DOD personnel and contractors should take to reduce risks associated with the public accessibility of digital information.

· Most (80 percent) of the training that DOD officials identified as educating DOD personnel about the digital profile, its associated risks, and best practices for countering risks, primarily focused on OPSEC. Training and awareness programs, according to the former Director of National Intelligence, are the most important weapons in the cyber-battlefield when it comes to personal devices and accounts.

In addition, OSD offices had limited collaboration to address risks associated with the digital profile—such as through the Defense Security Enterprise Executive Committee. The executive committee is a cross-functional governance body that includes stakeholders from across the department, including the General Counsel. So, the executive committee is well-positioned to support and facilitate efforts to reduce risk. Furthermore, multiple DOD components that we included in the scope of our review had not completed required security assessments, nor assessed the risks associated with the public accessibility of digital information.

In the forthcoming report, we made 12 recommendations to DOD to address these issues. Among our recommendations is that DOD:

· assess existing departmental security policies and guidance and make recommendations to the Secretary of Defense on updating policy and guidance;

· improve collaboration across the department to reduce the risks of information about DOD and its personnel becoming publicly accessible;

· review and assess security training to ensure that digital profile issues are considered in all security areas, and make appropriate recommendations; and

· ensure components are conducting required security assessments.

DOD concurred with 11 of the 12 recommendations and partially concurred with one recommendation. DOD also identified initial actions to implement them.

In conclusion, DOD has an opportunity to address risks affecting its personnel and operations by taking additional actions. By implementing our recommendations, DOD can improve the representation of digital profile threats in its existing policies and guidance. Also, DOD can ensure that digital profile issues are considered in training for all security areas: counterintelligence, force protection, insider threat, mission assurance, operational security, and program protection. Lastly, by conducting required security assessments DOD components can decrease the risk of not detecting vulnerabilities that malicious actors could otherwise exploit.

Chairwoman Ernst, Ranking Member Slotkin, and members of the subcommittee, this completes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions you may have at this time.

GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact Joseph W. Kirschbaum, Director, Defense Capabilities and Management, at Kirschbaumj@gao.gov; or Marisol Cruz Cain, Director, Information Technology and Cybersecurity, CruzCainm@gao.gov.

Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement.

GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony are Tommy Baril and Lee McCracken (Assistant Directors), Ashley Houston (Analyst-in-Charge), Nicole Ashby, Prianka Bose, Chris Businsky, Ash Huda, Claire Liu, Richard Powelson, and Angel Zollicoffer. Tracy Barnes, Mark MacPherson, Mike Silver, and Pamela Snedden also provided support to this testimony.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]GAO, Information Environment: Opportunities and Threats to DOD’s National Security Mission, GAO‑22‑104714 (Washington, D.C.: Sep. 21, 2022); Homeland Defense: Urgent Need for DOD and FAA to Address Risks and Improve Planning for Technology That Tracks Military Aircraft, GAO‑18‑177 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 18, 2018); and Internet of Things: Enhanced Assessments and Guidance Are Needed to Address Security Risks in DOD, GAO‑17‑514SU (Washington, D.C.: June 7, 2017).

[2]GAO will publish this report once the agency resumes operations.

[3]DOD Directive 5143.01, Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security (USD(I&S)) (Oct. 24, 2014) (incorporating change 2, Apr. 6, 2020).

[4]DOD Directive 5111.01, Under Secretary of Defense for Policy (USD(P)) (June 23, 2020) and DOD Instruction 2000.12, DOD Antiterrorism Support to Force Protection (June 11, 2025).

[5]DOD Directive 5137.02, Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (USD (R&E)) (July 15, 2020).

[6]DOD Directive 5122.05, Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs (ATSD(PA)) (Aug. 7, 2017).

[7]DOD Directive 5144.02, DOD Chief Information Officer (DOD CIO) (Nov. 21, 2014) (incorporating change 1, effective Sept. 19, 2017).

[8]DOD defines “DOD components” as the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the military departments, the Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Joint Staff, the combatant commands, the DOD Office of Inspector General, the defense agencies, the DOD field activities, and all other organizational entities within DOD.

[9]DOD Directive 5200.43, Management of the Defense Security Enterprise (Oct. 1, 2012) (incorporating change 3, effective July 14, 2020).

[10]DOD Instruction 8170.01, Online Information Management and Electronic Messaging (Jan. 2, 2019) (change 2, Mar. 12, 2025).

[11]DOD Instruction 5400.17, Official Use of Social Media for Public Affairs Purposes (Aug 12, 2022) (incorporating change 2, Feb. 14, 2025).

[12]Identity Awareness, Protection, and Management Guide, Washington, D.C., accessed September 22, 2025, https://www.odni.gov/files/NCSC/documents/campaign/DoD_IAPM_Guide_March_2021.pdf.