NAVY SHIPBUILDING

Improving Warfighter Engagement and Tools for Operational Testing Could Increase Timeliness and Usefulness

Report to Congressional Committees

GAO-26-108781

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Shelby S. Oakley at oakleys@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Operational testing—used to evaluate the capabilites of a new vessel to perform in realistic and relevant conditions—is critical to the Navy’s understanding of a vessel’s ability to counter the advances of its adversaries.

GAO found that Navy test and evaluation policy does not ensure consistent participation in test and evaluation working-level integrated product teams by key organizations representing the warfighter. Uncertainty about how warfighter organizations are represented in these teams—which are critical to test planning and execution for each shipbuilding program—poses challenges for ensuring that operational testing decisions reflect the current needs and interests of the fleet.

GAO also found that the Navy does not have a plan to replace the test capability provided by its aging self-defense test ship. The Navy uses this remotely operated vessel to test the self-defense systems that protect ships from incoming missiles. The Navy lacks a clear plan for replacing the unique capabilities of its test ship, as intended. This creates uncertainty for how the Navy will fulfill future operational testing requirements. A gap in, or loss of, such test capability could increase the risk to warfighters and ships in conflicts with adversaries.

In addition, while high-level Navy plans identify the need to invest in digital test infrastructure, GAO found that the Navy has yet to take coordinated action to respond to this need. For example, while some organizations had robust digital tools, GAO found that the Navy’s program-centric approach to fund, develop, and maintain digital test tools impedes investments in tools that could be widely used across shipbuilding programs. This program-centric approach also impairs the Navy’s ability to improve the timeliness and usefulness of operational testing. Without a cohesive plan for investing in the development and sustainment of its digital capabilities, the Navy risks not having the testing tools and infrastructure that it says it needs to confront an increasingly digital future—putting at risk U.S. warfighters’ ability to counter rapidly advancing adversaries.

Why GAO Did This Study

The U.S. Navy’s shipbuilding programs must deliver vessels with the capabilities needed to outpace new threats in an evolving maritime environment. Operational testing is central to the Navy demonstrating such capabilities.

A Senate report contains a provision for GAO to examine operational testing for Navy shipbuilding programs. GAO’s report addresses the extent to which (1) the Navy’s operational test and evaluation practices provide timely and useful information to acquisition decision-makers and warfighters, and (2) the Navy is developing and maintaining physical and digital test assets to support operational test and evaluation of its vessels. This is the public version of a sensitive report GAO issued in September 2025.

GAO reviewed operational test and evaluation documentation related to Navy vessels, interviewed officials from the Navy and the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and conducted site visits to three naval warfare centers and the Navy’s self-defense test ship.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations to the Navy, which are intended to ensure that the Navy (1) has consistent representation from warfigher organizations in test planning, (2) makes a decision about maintaining the test capability currently provided by its self-defense test ship, and (3) establishes a cohesive plan for investing in digital test infrastructure. The Navy did not concur with GAO’s first recommendation, partially concurred with the second, and concurred with the third. GAO maintains that all three recommendations are warranted.

Abbreviations

CBTE capabilities-based test and evaluation

CNO Chief of Naval Operations

DOD Department of Defense

DOT&E Director, Operational Test and Evaluation

DT developmental testing

IT integrated testing

NAVSEA Naval Sea Systems Command

OPTEVFOR Operational Test and Evaluation Force

OT operational testing

T&E WIPT test and evaluation working-level integrated product team

TEMP test and evaluation master plan

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Congressional Committees

The U.S. Navy faces significant challenges to maintaining maritime superiority from the rapid modernization and expansion of naval capabilities by its adversaries. The Navy is also attempting to overcome the cumulative effects of persistent performance shortfalls within its shipbuilding programs. As we concluded in March 2025, while the Navy strives to improve its shipbuilding performance, marginal changes within its existing acquisition approach are unlikely to provide the systemic change needed to significantly improve shipbuilding outcomes.[1] To successfully confront these challenges, the Navy’s shipbuilding programs must demonstrate that they can deliver new vessels with the advanced and adaptable capabilities needed to outpace new threats. Operational testing is intended to play a key role by supporting timely, rigorous evaluation of the capabilities provided by these vessels under realistic combat conditions.[2] The resulting test data can then inform warfighters’ understanding of the performance they can expect from their vessels and the options available to Navy commanders in the fleet when confronting the range of growing maritime threats.

We have found, however, that it is common for Navy shipbuilding programs to have long acquisition cycle times and significant delays to the delivery of lead vessels and their availability for this testing.[3] These delays diminish the timeliness and potential usefulness of operational testing to inform acquisition decisions and the fleet’s understanding of the operational capabilities provided by new vessels. For example, by the time the Navy expects to complete initial operational test and evaluation for the lead Columbia class submarine, more than half of the program’s vessels are planned to be on contract, and several are scheduled to be under construction. Such conditions can leave sailors to first learn the capabilities and limitations of new vessels through other ship operations—such as training, fleet exercises, or the ship’s initial deployments—reducing the potential usefulness of operational testing to the fleet.

Senate Report 117-130 accompanying a bill for the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 contains a provision for us to examine operational test and evaluation for Navy shipbuilding programs, citing concerns about the adequacy of the Navy’s current plans and activities. This report addresses the extent to which (1) the Navy’s operational test and evaluation practices provide timely and useful information to acquisition decision-makers and warfighters, and (2) the Navy is developing and sustaining physical and digital test assets to support operational test and evaluation of its vessels.

This report is a public version of a sensitive report we issued in September 2025.[4] This public version has the same objectives, uses the same methodology, and makes the same recommendations as the sensitive report. The sensitive report includes some statements that the Department of Defense (DOD) determined are controlled unclassified information that must be protected from public disclosure.[5] Some of those statements helped support our recommendations and conclusions. However, our conclusions and recommendations remain sufficiently supported by the information approved for public release.

We have omitted the following types of information from the sensitive report in this public version:

· The background and second objective omit specific statements on the type of testing that the Navy’s remotely-controlled self-defense test ship enables that cannot be safely performed using ships with crew onboard.

· The first objective omits statements related to the relevance of certain planned testing from the fleet’s perspective.

· The second objective omits certain statements about inherent limitations to performing operational testing for Navy shipbuilding programs that affect planning and execution. It also omits certain statements on the Navy’s current self-defense test ship related to its future use, retirement, and potential replacement. Further, this objective omits certain statements on the capabilities and limitations of Navy digital test and evaluation assets and associated practices.

To assess the timeliness and usefulness of the Navy’s operational test and evaluation practices for its shipbuilding programs, we reviewed relevant statutory requirements and DOD and Navy policies and guidance for shipbuilding acquisition and test and evaluation. We also reviewed test and evaluation master plans (TEMP) for nine Navy shipbuilding programs representing different classes of surface and undersea vessels. Further, we reviewed relevant reporting on the programs from test and evaluation organizations within the Navy and the Office of the Secretary of Defense. This reporting included operational assessments, reports on initial operational test and evaluation results, and annual reports. Additionally, we interviewed officials from Navy organizations associated with shipbuilding requirements, acquisition, and test and evaluation, as well as officials from the Office of the Director, Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E). We compared the results of our documentation review and interviews to leading practices—including those for testing and evaluation—that we previously identified for product development.[6]

To assess the Navy’s efforts to develop and sustain physical and digital assets that support operational test and evaluation, we conducted site visits to observe the Navy’s self-defense test ship and the facilities at three Navy warfare centers. We also reviewed Navy documentation and interviewed Navy and DOT&E officials about the test assets used to support operational test and evaluation for shipbuilding programs. This included assessing the Navy’s activities related to maintaining and expanding the Navy’s physical test assets, such as its self-defense test ship, and digital test assets, such as advanced modeling and simulation for submarine torpedo strike capabilities or combat system suites for surface vessels. See appendix I for a more detailed description of our objectives, scope, and methodology.

The performance audit upon which this report is based was conducted from April 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We subsequently worked from September 2025 to January 2026 to prepare this version of the original sensitive report for public release. This public version was also prepared in accordance with these standards.

Background

Overview of Test and Evaluation for Navy Shipbuilding Programs

As outlined by DOD guidance, test and evaluation activities serve an integral part in developing and delivering Navy vessels that meet operational performance expectations.[7] These activities provide opportunities to collect data on system performance and identify and resolve deficiencies before programs make key acquisition decisions and new vessels are delivered to support fleet operations. Test and evaluation also offers opportunities to build knowledge on the capabilities and limitations of Navy vessels to inform decisions on how to effectively operate vessels to fulfill their missions.

As outlined by DOD acquisition policy for major capability acquisitions, the Navy develops requirements for each new shipbuilding program that set expectations for the vessel’s operational performance.[8] These can range from propulsion-related requirements, like speed and endurance, to more combat-oriented ones, like offensive strike and self-defense capabilities. Once the operational requirements are developed, the Navy determines its planned cost and schedule to design and construct a vessel with the desired operational performance. Collectively, these cost, schedule, and operational requirements form what is known as the acquisition program baseline. The shipbuilding program manager’s job is to execute the program to uphold the vessel’s cost and schedule expectations while meeting the operational requirements.

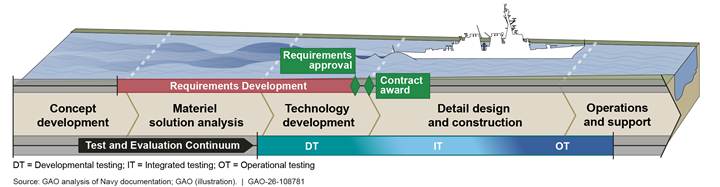

Test and evaluation serves as a key indicator for whether Navy shipbuilding programs are on track to deliver vessels that meet their performance requirements. As described by DOD guidance, programs generally begin with developmental testing and then move to live fire and operational testing as the programs mature and increase their focus on the operational capabilities expected of the vessels to fulfill their missions.[9]

· Developmental testing. Conducted by contractors, university labs, various DOD organizations, and government facilities like the Navy’s warfare centers, this testing is designed to provide feedback on a vessel’s design and combat capabilities before initial production or deployment. For example, the Naval Surface Warfare Center, Carderock Division uses its facilities to test and characterize maneuvering and speed as well as acoustic and electromagnetic signatures of ship models.

· Live fire testing. Conducted by the government, this testing is intended to support the evaluation of a system’s vulnerabilities and lethality under realistic conditions.[10] For Navy vessels, live fire testing can include full ship shock trials, which employ an underwater charge at a certain distance to identify survivability issues for the vessel and its key systems.

· Operational testing. Conducted by the government (i.e., operational test agency), this testing is designed to evaluate a system’s effectiveness and suitability to operate in realistic conditions. For new classes of Navy vessels or major design modifications to existing classes (referred to as flights), the initial operational test and evaluation is intended to inform decisions on the introduction of new vessels into the fleet.[11]

· Integrated testing. This type of testing takes a holistic view of developmental and operational test objectives and leverages opportunities for test events to meet objectives for both. Integrated testing relies on collaboration between developmental and operational test officials. Such testing can help identify deficiencies in a system’s design and inform corrective fixes earlier than would be achieved if programs waited until operational testing to test and evaluate system performance.

In general, shipbuilding programs fulfill their developmental and operational testing needs using a mix of modeling and simulation and live physical testing. For modeling and simulation, the purpose and expectations for these digital representations of systems vary depending on the type of testing they are intended to support. Modeling and simulation that has been verified, validated, and accredited to confirm it sufficiently represents a physical system can enable and augment the evaluation of operational effectiveness and suitability of a system.[12] It similarly can be used to evaluate survivability and lethality effects.

For live testing, the Navy uses physical test assets that are representative of the systems used by the fleet or the actual vessels from the fleet to evaluate operational capabilities. Along with demonstrating physical performance, live testing provides the data needed to ensure that a model or simulation can provide an accurate representation of real-world performance. Representative physical test assets, such as targets that emulate certain missile threats or the Navy’s remotely controlled self-defense test ship, provide for operationally realistic live testing.

The Navy’s self-defense test ship, the ex-Paul F. Foster, a Spruance class destroyer, has served as a key physical test asset for the Navy since 2006. This test ship provides critical and unique operational test and evaluation capabilities that help meet statutory requirements.[13] Among other capabilities, the Navy’s self-defense test ship provides the Navy with a remotely controlled test asset that can be used to perform live fire testing at sea. This includes live testing to demonstrate the operational performance of Navy ship self-defense systems at close range.[14] Testing performed using the test ship also provides the data needed to validate Navy modeling and simulation capabilities. The Navy uses these models and simulations to characterize and evaluate how the systems that are designed to protect ships from missiles will behave as incoming missiles are en route.

Operational Test and Evaluation Practices for Navy Vessels

The Navy is expected to conduct operational testing of a vessel in a manner that is as realistic as possible, using fleet personnel to operate the vessel. To accomplish this, program managers must lead extensive test planning and coordination with numerous stakeholders. This planning supports a program’s development of a TEMP.

Required to support key program milestone reviews, a program’s TEMP is critical to developing and documenting agreement between shipbuilding program and test and evaluation stakeholders. As reflected in DOD guidance, the TEMP represents an agreement between stakeholders with varied interests that balances the need for adequate testing and the cost, schedule, or other considerations for each shipbuilding program.[15] Such a plan establishes a commonly understood focus and scope of the activities required to evaluate the technical requirements and operational performance of a vessel as it progresses through the acquisition life cycle.[16] This includes the resources needed to complete testing, how the major test events and test phases link together, and the criteria by which the vessel will be tested and evaluated. In developing the TEMP, each program manager—who is largely responsible for funding all testing—faces the challenge of trying to maximize learning and confidence in the vessel, while controlling the testing cost and schedule.

As demonstrated by the TEMPs for shipbuilding programs, operational test and evaluation is generally not a singular event. Rather, this testing occurs through a series of phases and events that often spans many years. For example, the CVN 78 Ford class aircraft carrier program’s TEMP outlines several integrated test phases beginning in July 2014 that supported operational testing needs before a period of initial operational test and evaluation period that began in August 2022. This operational testing period extended to March 2025, and testing may not be complete until fiscal year 2027 because of the carrier’s deployment schedule.

Operational Test and Evaluation Stakeholders for Navy Vessels

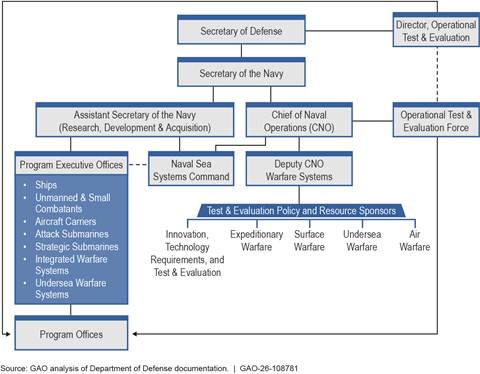

The planning and execution of operational test and evaluation for Navy vessels includes stakeholder involvement from organizations within the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the Navy. Figure 1 shows organizations with significant involvement in test planning and execution for Navy vessels.

Figure 1: Primary Department of Defense Organizations Involved in Operational Test and Evaluation of Navy Vessels

Note: The Marine Corps has its own operational testing agency—the Marine Corps Operational Test and Evaluation Activity—that supports test planning and evaluation for Marine Corps issues related to Navy shipbuilding programs, as needed, through coordination with the Navy’s Operational Test and Evaluation Force.

Operational testing for Navy shipbuilding programs is managed by the Navy’s Operational Test and Evaluation Force (OPTEVFOR). As the Navy’s independent operational test agency, OPTEVFOR conducts operational test and evaluation of the Navy’s vessels and their systems against relevant threats and under realistic conditions. OPTEVFOR conducts testing in accordance with the operational test plan. This plan, which builds off an integrated evaluation framework that is resourced by the TEMP, provides a more detailed scope and methodology for operational test and evaluation of the system under test (i.e., ship, submarine, or weapon system, such as a radar or missile).[17] The operational test plan must be approved by DOT&E prior to the start of testing.[18] Residing outside of the Navy’s acquisition and operational test communities, DOT&E provides the Secretary of Defense and Congress with an independent perspective on operational testing activities and results for Navy shipbuilding programs. DOT&E’s responsibilities include approving all operational testing in shipbuilding programs’ test plans, assessing the adequacy of test execution, and reporting to the Secretary of Defense and Congress on all operational test and evaluation results.[19] Collectively, these operational test and evaluation organizations seek to minimize the operational risk accepted by the fleet and maximize the probability of mission success through testing that reflects efficient use of limited resources.

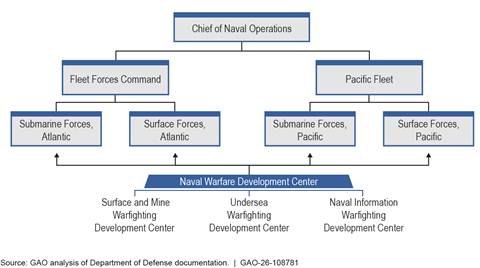

Operational testing presents opportunities to inform decision-making within the fleet on the operation of new vessels. This testing also generates information characterizing vessel performance that can be used by organizations under the U.S. Fleet Forces Command and Pacific Fleet to understand the extent to which new capabilities can be used to confront existing and emerging threats. Such organizations include the Navy’s warfighting development centers, which are responsible for developing the tactics, techniques, and procedures used to operate the vessels in combat scenarios. Operational test information can also be used by the Navy’s type commands, such as the Surface Forces and Submarine Forces for the Pacific Fleet, to fulfill their responsibilities for the crewing, training, and equipping associated with Navy vessels in the fleet. Further, test information on operational performance can support the fleet and combatant commanders, who seek the best information available about the capabilities and limitations of the Navy’s assets to optimize how they employ these assets in the defense of the nation. Figure 2 shows the organizational structure for these Navy fleet forces organizations related to the operational performance of Navy vessels.

Navy Strategy for Operational Test and Evaluation

To support future operations and combat advancing capabilities of adversaries, the Navy adapted its strategy for test and evaluation planning and execution. The new strategy, formally outlined in Navy policy and guidance updates from 2022 and 2024, respectively, focuses on the use of capabilities-based test and evaluation (CBTE) enabled by mission-based test design.[20] Since distributing initial implementation guidance for CBTE in July 2021, the Navy has been working to implement the strategy across its acquisition programs to support test and evaluation improvements.

The intent of a CBTE strategy is to efficiently use integrated testing to meet contractor, developmental, and operational testing needs and help inform decisions on design and requirements as early as possible. To do this, CBTE focuses on continuous testing from the beginning of system development until the end of testing, with the singular goal of demonstrating a system’s capability to meet the intended mission needs. As part of a CBTE strategy, test plans are intended to leverage fleet exercises and program-to-program collaboration so that vessels and their systems are tested as part of an enterprise rather than in a platform- or system-specific manner.

Along with other efficiency and timeliness goals, the Navy expects CBTE to provide a better understanding of capabilities and gaps of the vessel under test and the system of systems that support it. The term “system of systems” reflects how modern warfighting systems typically interact with one another to provide warfighters with operational capability. For example, a radar interacts with a fire control computer, which interacts with a weapon launcher, to then launch a weapon, which communicates to the radar for guidance to its target.

The Navy’s CBTE policy and guidance state that the incorporation of mission-based test design in all testing phases is a key enabler for this test strategy. Mission-based test design involves collaborative planning of testing that is operationally relevant across the testing continuum. This design approach also attempts to avoid testing that focuses on meeting contract specifications without regard for whether it provides warfighters with capability needed to fulfill their missions.

As described by Navy guidance, mission-based test design uses the required operational capabilities and projected operating environment mission areas to determine the required mission capability contributions that a system is expected to deliver.[21] The tasks required to complete a system’s expected mission are defined and then prioritized. In turn, the tasks inform how performance is measured and the data needed to support evaluation. Test events are designed for data to be collected on identified performance measures, with these data compiled and analyzed to evaluate a system’s capabilities as part of a Navy system of systems.

Leading Practices for Product Development

Since 2009, we have applied leading practices in commercial shipbuilding to our work evaluating U.S. Navy shipbuilding programs. As we previously reported, this work has demonstrated that leading practices from commercial industry can be applied thoughtfully to Navy shipbuilding acquisition to improve outcomes, even when cultural and structural differences yield different sets of incentives and priorities.[22] In July 2023, we reported on how leading companies use iterative cycles—which include test and evaluation activities—to deliver innovative products with speed.[23] These continuous cycles include common key leading practices, such as obtaining user feedback to ensure that capabilities are relevant and responsive to user needs. Activities in these iterative cycles often overlap as the design undergoes continuous user engagement and testing. As the cycles proceed, leading companies’ product teams refine the design to achieve a minimum viable product. A minimum viable product has the initial set of capabilities needed for customers to recognize value from fielding the product and can be followed by successive iterations. Leading companies use modern design and manufacturing tools and processes informed by continuous testing to produce and deliver the product in time to meet their customers’ needs.

The iterative development structure is also enabled by digital engineering throughout the product’s life. This includes the use of digital twins—virtual representations of physical products—and digital threads—a common source of information that helps stakeholders make decisions, like determining product requirements. A digital twin can rapidly simulate the behavior of different designs and feed data into a digital thread for a product. Maintaining a digital thread that captures digital records of all states of a product throughout development and testing enables stakeholders to predict performance and optimize their product. It also provides real-time, reliable information to users that can be used to identify areas where the product’s design can provide the most value.

As we previously found, iterative development practices contrast with traditional, linear product development practices. Table 1 describes some of the differences between these practices.[24]

|

|

Linear development |

Iterative development |

|

Requirements |

Requirements are fully defined and fixed up front |

Requirements evolve and are defined in concert with demonstrated achievement |

|

Development |

Development is focused on compliance with original requirements |

Development is focused on users and mission effect |

|

Performance |

Performance is measured against an acquisition cost, schedule, and performance baseline |

Performance is measured through multiple value assessments—a determination of whether the outcomes are worth continued investment |

Source: GAO analysis. | GAO‑26‑108781

In December 2025, we found that DOD-wide and Navy policies related to test and evaluation do not fully reflect key tenets of our leading practices for product development.[25] For example, we found that DOD-wide test and evaluation policies lack consistent expectations for tester involvement in acquisition strategy development for programs, as well as iterative testing practices that include ongoing user input throughout testing and use of digital twins and digital threads. We also found that the Navy’s test and evaluation policy does not further reflect leading practices beyond what is in DOD-wide test and evaluation policies.[26] Based on these recent findings, we made four recommendations to DOD and three recommendations to the Navy to address the identified shortfalls by revising their test and evaluation policies to reflect leading practices. DOD concurred with one recommendation and partially concurred with the remaining three recommendations. The Navy partially concurred with two recommendations and did not concur with one recommendation. We maintain that these recommendations are warranted to facilitate operational test and evaluation improvements.

Navy’s Test and Evaluation Strategy Is Limited by Shipbuilding Acquisition Practices and Shortfalls in User Involvement

While the Navy has updated its policy and guidance to support test and evaluation by incorporating a CBTE strategy, its acquisition practices prevent the strategy’s full implementation. Navy shipbuilding programs continue to use traditional acquisition practices that lock down requirements and ask shipbuilders to design vessels to meet them. This approach does not align well with the iterative development principles needed to take full advantage of a CBTE strategy. Additionally, the Navy’s operational test and evaluation practices do not reflect leading practices that produce consistent engagement with key user representatives from the fleet to inform test planning and implementation. For shipbuilding programs, such user involvement would also help ensure operational testing aligns with how the fleet expects to use the capabilities provided by its new vessels. Further, it would help ensure that direct input from fleet organizations on the threats they face contributes to decision-making related to operational testing.

Navy’s Test and Evaluation Strategy Is Impeded by Shipbuilding Acquisition Practices

Misalignment between the Navy’s CBTE strategy and acquisition practices impede the Navy’s recent efforts to improve the timeliness and usefulness of operational test and evaluation. The Navy’s overall test and evaluation policy and guidance updates from 2022 and 2024, respectively, as well as OPTEVFOR guidance from 2021 and Naval Sea Systems Command’s 2025 policy revisions, outline expectations for Navy shipbuilding programs to implement a CBTE strategy using mission-based test design.[27] As described by OPTEVFOR guidance, this strategy and test design is intended to support an iterative, systems engineering approach to testing that focuses on the operational capabilities expected of a vessel to support its missions. A senior Navy test and evaluation official from the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations stated that CBTE adoption by programs is in the early stages and continues to mature. Further, OPTEVFOR officials said that consistent implementation of CBTE across shipbuilding programs has proved challenging because the Navy’s system commands have not uniformly required adoption of the strategy since its introduction.

Overall, we found that a CBTE strategy enabled by mission-based test design would generally align with iterative product development principles used by leading commercial companies if the Navy used an iterative acquisition approach for its shipbuilding programs.[28] However, as we recently found, the Navy’s shipbuilding programs generally use a linear acquisition approach.[29] As shown in figure 3, a linear acquisition approach executes phases and milestones sequentially, with testing advancing from early developmental testing through operational test and evaluation as the program proceeds through its acquisition phases.

Figure 3: General Illustration of Linear Acquisition Approach, Including Test and Evaluation, for Navy Shipbuilding Programs

Further, under a traditional linear acquisition approach, the Navy develops and locks down requirements and specifications (i.e., detailed requirements) for a vessel several years in advance of building the first ship. In doing so, the Navy requires shipbuilders to design and build vessels to meet strict specifications. The Navy’s traditional test and evaluation practices that preceded its recent CBTE efforts stem from the linear acquisition approach. Navy test officials told us that these test practices were inefficient and inadequate, focusing on testing to a checklist of specifications developed years before operational test and evaluation. They added that these practices created the potential for operational testing to successfully demonstrate that a system met previously defined specifications without regard for whether the system met the fleet’s operational needs. The Navy’s continued reliance on a linear acquisition approach will undermine CBTE’s stated intent to generate earlier, more useful information on operational performance to inform acquisition decisions related to vessel design and requirements. It will also hinder the ability of operational testing to provide timely information that supports the fleet’s understanding of a vessel’s capabilities and limitations.[30]

Despite the stated limitations that the Navy’s acquisition practices impose on its shipbuilding programs fully implementing a CBTE strategy, our review of information from nine Navy shipbuilding programs indicates that these programs are working to implement CBTE principles in their testing activities. For example, program officials from the Navy’s America and San Antonio classes of amphibious vessels stated that CBTE is an inherent part of their overall test and evaluation strategies. They noted collaboration with OPTEVFOR that supports integrated testing and operational planning, estimates for test and evaluation resource needs, and definition of the minimum adequate testing required to confirm the operational requirements and capabilities for both ship classes.

We also found through our review of TEMP drafts and updates that programs generally have taken action to implement CBTE principles since the Navy put out its initial guidance in 2021. For example, the February 2024 draft plan for the Medium Landing Ship outlines a CBTE strategy that includes early collaboration with a range of stakeholders to effectively resource testing and leverage integrated testing opportunities using mission-based test design. The stakeholders include, among others, OPTEVFOR, the Expeditionary Warfare Directorate within the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, and Fleet Forces.

The Navy could address the challenges we found with acquisition practices impinging on effective CBTE implementation across shipbuilding programs by implementing a number of recommendations we made in 2024. Specifically, in December 2024, we recommended that the Navy revise its acquisition policies and relevant guidance to reflect leading practices that use continuous iterative cycles that ensure timely designs that meet user needs.[31] In May 2024, we also made a series of recommendations that would align Navy ship design with the leading practices used by commercial ship buyers and builders to more rapidly deliver new vessels with needed capabilities.[32] The Navy generally agreed with the recommendations and is in the process of addressing them. If the Navy fully implements these recommendations, it will have a better opportunity to realize the full benefits expected through its CBTE strategy.

Navy’s Test Planning Process Does Not Consistently Ensure Key Leading Practices for User Input

We found that the Navy’s operational test and evaluation process for its shipbuilding programs—and DOD and Navy policy and guidance governing them—does not fully incorporate leading practices that ensure input from users.[33] As outlined in DOD and Navy policies, Navy shipbuilding programs are required to establish teams to support efficient test planning and execution. These teams, known as test and evaluation working-level integrated product teams (T&E WIPT), are intended to support collaboration and appropriate representation of the interests of stakeholders in the test and evaluation strategy for each program.[34] DOD and Navy policies also indicate that program offices should create these teams early in the acquisition process to estimate the tests necessary for proving out program requirements and associated costs. These teams should also consider the operational capabilities needed to meet the fleet’s needs.

According to DOD policy, T&E WIPTs are expected to include representatives from programs, systems engineering, developmental testing, the intelligence and requirements communities, OPTEVFOR, and DOT&E.[35] The teams are also expected to include representatives for system users (i.e., warfighters). However, DOD policy does not define the personnel or organizations intended to fulfill the system users’ role, nor does the Navy’s test and evaluation policy and guidance.[36]

We found different perspectives from Navy officials on the fleet’s participation in T&E WIPTs and how warfighters are represented in the teams. For example, program offices indicated levels of fleet participation in test planning for shipbuilding programs ranging from limited or no involvement for several surface ships to more coordinated fleet interactions for submarines. Officials from OPTEVFOR and the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations told us that they represent the warfighters. However, fleet organizations can provide different and distinct insights based on their direct experiences in combating current operational threats. Officials from Navy fleet organizations, such as the type commands that are responsible for crewing, training, and equipping Navy vessels, noted limited interaction with OPTEVFOR or other relevant organizations in test planning. They also said that their lack of involvement in T&E WIPTs prevents them from being well informed about test planning and results or helping to ensure that testing reflects the most current threats faced by the fleet.

Navy officials across several acquisition, requirements, and fleet organizations told us that consistent representation of fleet forces organizations—which include the Navy’s type commands and warfighting development centers, among others—in T&E WIPTs could improve the inputs and outcomes for operational testing. For example, an official from a Navy warfighting development center told us that they would benefit from earlier opportunities to provide input on behalf of the fleet to support test planning. The official cited specific issues with future planned testing for certain Navy systems as an example of why the centers want to be involved earlier in test activities.[37] The official also noted that they could provide their fleet organization’s perspective on the relevance of certain testing to inform test planning.

Our leading practices for product development and ship design—both with direct relationships to testing—emphasize the need for consistent user engagement.[38] Such involvement helps ensure that Navy decision-making for ship capabilities, requirements, and design is informed by the personnel who are focused on the operation of the vessels once they are part of the fleet. Having representation on T&E WIPTs gives organizations opportunities to help set expectations and inform decisions on test planning and event design for Navy vessels and their systems. For example, OPTEVFOR uses its participation in these teams to inform programs of the data that will be required to demonstrate effective and suitable operational performance.

Consistent and direct participation in T&E WIPTs by fleet representatives could help ensure that operational tests are conducted against the most current threats faced by the fleet.[39] It could also increase the fleet’s confidence in the operational capabilities of vessels once they are fielded and deployed. Further, it could help ensure that decisions made through T&E WIPTs include direct input from organizations that are best positioned to accept risk on behalf of the fleet and understand the current operational realities. Officials from the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations noted that direct fleet representation in T&E WIPTs could, for example, allow the fleet to voice its willingness to accept the risks of fielding a new capability despite limitations identified through testing, depending on the operational need for the more limited capability.

The lack of clarity for whether and how warfighters under the U.S. Fleet Forces Command and Pacific Fleet should be represented in T&E WIPTs for shipbuilding programs creates uncertainty for how the Navy can ensure consistent direct fleet input in collaborative test planning and execution for shipbuilding programs. It also misses opportunities for fleet organizations, which are uniquely positioned to represent the interests of system users, to inform decisions on how to maximize the usefulness of testing to a vessel’s eventual operators in the fleet. Further, without consistent representation in T&E WIPTs and associated test design, the fleet is left to accept decisions based solely on the priorities and goals of others within the Navy, such as acquisition programs or test and evaluation organizations.

Navy Has Not Developed or Sustained Physical or Digital Assets Needed to Improve Operational Testing

The Navy must navigate inherent limitations, such as competing schedule demands and test range limitations, when planning and executing operational test and evaluation for its shipbuilding programs. As part of overcoming test limitations, the Navy relies on key physical test assets like its self-defense test ship. However, the Navy has not decided how it will replace the test capability provided by its aging test ship. This situation presents uncertainty for how the department will address future operational testing needs. The Navy also uses digital test assets to fulfill operational testing requirements. But, it does not have a cohesive plan for developing and sustaining such test capabilities and infrastructure to support more timely and useful enterprise solutions that benefit programs, testers, and the fleet.

Navy Faces Limitations When Planning and Executing Operational Testing for Shipbuilding Programs

Inherent limitations to performing operational testing for Navy shipbuilding programs affect planning and execution. These limitations, which present challenges to using operational testing to fully understand the operational capabilities of vessels, include the following:[40]

· Vessel availability for testing. To ensure realistic and relevant operational testing, Navy shipbuilding programs typically need to wait until they have a vessel from the new class available to perform a significant amount of required operational testing. However, with the fleet’s documented priorities focused on meeting operational needs, training, and maintenance, these activities can take precedence over having a vessel available for operational test and evaluation. Once constructed and delivered, Navy vessels are often tasked with operations and training missions.

While programs and test and evaluation organizations work to leverage opportunities to meet operational testing needs as part of these other vessel activities, they also can affect scheduling for dedicated operational test events. Additionally, accounting for maintenance in test scheduling can prove challenging based on the persistent problems we previously found in cycling Navy vessels in and out of maintenance as planned.[41] Overall, these conditions can contribute to uncertainty for when operational test events will be executed. Further, they can result in operational testing periods that span months or years after the lead ship is delivered. The extended periods for testing reflect the tradeoffs made by the Navy between having new vessels available to meet certain priorities and delaying the overall learning from operational testing that can be used to inform the fleet about the operational capabilities of its vessels.

· Test asset availability. Limited access to physical test assets that sufficiently emulate the operational performance of specific threats can present challenges for conducting certain tests. For example, we found test plan documentation that cited a limitation to testing based on the Navy not having developed a specific test target that would be needed to execute a certain test.

· Crew and vessel safety. Safety requirements, such as those when testing ship self-defense systems, can preclude the Navy from conducting realistic operational test and evaluation using vessels with crew onboard. To complete operational testing for self-defense systems under certain conditions, the Navy instead uses its self-defense test ship—a unique, remotely-operated test asset with no crew onboard. Use of the test ship mitigates safety risks and enables more realistic testing to assess operational performance.

· Environment and weather. It can be challenging for testing to account for the full range of maritime environments for which the Navy expects its vessels to operate. The geographic location of test ranges and their environmental conditions can pose testing limitations. For example, environmental regulations, such as those related to the protection of marine mammals, can limit testing. Weather conditions can also prevent test events from occurring as planned or undermine the relevance of test results if the conditions create impediments to completing realistic or relevant tests.

· Reliability of test data and assets. Digital and physical test assets can experience limitations in providing the expected data and performance to support test events. Digital assets, such as a modeling and simulation test bed for a vessel’s combat system, often rely on data from live physical testing, such as missile firings from a test ship or crewed vessel. When physical test data are not available, it limits the Navy’s ability to validate performance information from modeling and simulation. For physical test assets, such as an aerial target or the ship undergoing testing, if a problem with the test asset’s performance arises during a test event, it has the potential to undermine the ability to evaluate operational performance of the vessel being tested. Such problems can lead to the need for additional testing to fulfill operational test requirements.

· Resources and test scoping. Although relatively inexpensive when compared to the typical overall cost of a Navy shipbuilding program, investing in a mix of physical and digital testing and performing operational tests onboard a crewed vessel can require significant funding. Much of the testing cost is borne by program offices. As DOT&E reported in January 2025, among all DOD programs under its oversight with approved test plans and strategies, 21 programs did not have adequate funding to support planned test execution.[42] Another 26 programs required updates to their test strategies to account for program changes that may affect testing or resource requirements. Based on resourcing realities, decisions about adequate operational testing generally come with an acknowledgment of the limits to how much of a vessel’s total operational capabilities will be demonstrated through testing.

Continued Availability of Critical Test Ship Capability Is Uncertain

The Navy relies on key physical test assets, such as its remotely operated self-defense test ship, to overcome some testing limitations. For example, as we previously discussed, the Navy’s ex-Paul F. Foster destroyer, which has served as a self-defense test ship since 2006, enables operational testing that the Navy cannot replicate using ships with crew onboard due to safety restrictions. Such testing helps ensure sufficient operational realism for testing to demonstrate the performance of ship self-defense systems without putting crew or the ship in significant danger.[43]

The Navy used the self-defense test ship extensively from 2018 through 2020 to address operational testing needs for the CVN 78 Ford class aircraft carrier and the DDG 1000 Zumwalt class destroyer. Since that time, the Navy has continued using the test ship to conduct self-defense and other test events. Over the next few years, the test ship’s operational testing activities are expected to focus on demonstrating certain ship self-defense capabilities.[44] The Navy intends to complete this testing before the end of the decade.

Aging Self-Defense Test Ship in Poor Condition

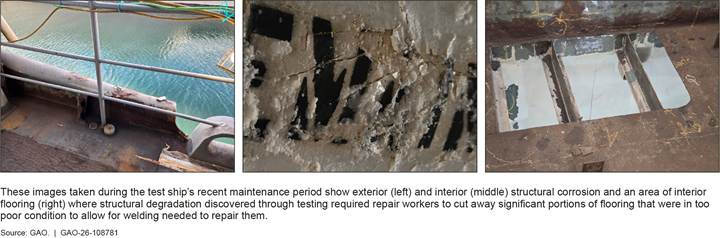

We found that the poor physical condition of the Navy’s self-defense test ship—due, in large part, to age-related factors—poses significant challenges to its continued operation through the end of the decade or beyond. During our shipyard site visit to observe the test ship’s condition during its recent maintenance period, Navy maintenance officials outlined significantly degraded material conditions and obsolescence issues. They noted that these issues are exacerbated by the ship being the only one left in its class operating after nearly 50 years of combined service in the fleet and as a test ship. For example, we observed aluminum and steel degradation in the hull structure throughout the ship. The maintenance officials explained that this creates obstacles to, or outright prevents, the use of welding to complete certain repairs. Since attempting conventional repairs to address this type of degradation could lead to more significant damage to the vessel, maintenance personnel have instead used composite patches extensively for repairs. Navy maintenance officials added that they will need to use bespoke repair solutions going forward because of the poor material condition and lack of spare parts due to the ship being the last one of its design. Figure 4 provides examples of the test ship’s structural condition and ongoing repair work that we observed before maintenance period activities to improve the ship’s condition concluded in May 2025.

Figure 4: Examples of Material Condition and Ongoing Repair Work for the Navy’s Self-Defense Test Ship as of November 2024

As with the hull structure, the test ship’s equipment and components also suffer from significant degradation. Navy maintenance officials stated concern with leaking and general deterioration of the test ship’s tanks, particularly in the middle of the ship where constant vibration occurs when the ship is operating. They noted that the tops of several tanks, which hold fuel or water, had holes in them and cited one instance where cleaning a tank using low level water pressure blew a hole in it. An official from the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations noted that multiple tanks were opened, inspected, and repaired by the conclusion of the recent maintenance period. Figure 5 shows the test ship in the water during recent maintenance.

Navy maintenance officials also stated concerns related to the test ship’s propulsion shafts. An official from the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations noted that inspections completed shortly before the recent maintenance period found no significant deficiencies and certified the shafts for unrestricted operations. However, according to Navy maintenance officials, the test ship’s shafts are the only ones left of their kind. As a result, if the shafts break and are pulled for maintenance and cannot be fixed, the Navy has no immediate replacement options, though an official noted that the Navy has an option to contract for the acquisition of new shafts.

In addition, the performance of the test ship’s aging drive console system poses risk to continued operations. Specifically, Navy maintenance officials said that the system, which enables remote-controlled operation of the test ship, has had persistent problems with communication errors between the ship control console and steering. When these errors occur, operators lose functionality for a portion of the ship’s steering control, which poses risk of damage to the ship and the environment around it. Based on the overall degraded conditions, a member of the contractor crew that operates the test ship raised concerns about the ability to safely operate the ship following its maintenance period. However, an official from the Naval Surface Warfare Center, Port Hueneme Division told us after the recent maintenance period concluded that the drive system is slated for an upgrade to improve its stability. The official added that the Navy has preplanned responses and procedures in place to retake control of the ship before any danger is posed by the system failing to function as intended.

Navy maintenance officials said that in addition to age, inconsistent maintenance has contributed to the ship’s degraded conditions and poses challenges to continuing to effectively operate the current self-defense test ship. For example, a senior Navy official told us that the test ship has not received maintenance in a shipyard dry dock since 2012—a relatively long period for a Navy ship that is nearly 50 years old.[45] The official also noted that the ship left the maintenance period in 2012 with outstanding material concerns unaddressed. Further, Navy Board of Inspection and Survey reports from 2017 and 2022 speak to the uneven test ship maintenance over time.[46] Specifically, the board’s 2017 inspection report states that the Navy was operating the test ship with critical safety issues and the Navy’s lack of adherence to maintenance standards could prevent the ship from reaching its intended service life. The 2022 inspection report states that the Naval Surface Warfare Center, Port Hueneme Division took significant action to enact the board’s 2017 recommendations for improvement, while also noting significant degradation to certain critical test ship capabilities related to damage control, propulsion, and communications. The 2022 report also noted extensive corrosion concerns for the test ship.

An official from the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations stated that the Navy made the decision to not execute a maintenance availability for the test ship in the 2018-2022 time frame. This decision was made because several programs were significantly behind schedule and making the test ship unavailable would have contributed to further delays for those programs. As cited in Navy test ship documentation, the Navy pursued a dry dock maintenance for the ship in fiscal year 2022 but did not receive funding to support it. The Navy considered a dry dock maintenance again for 2024 but ultimately decided, based on the recommendations of its technical community, to conduct maintenance activities in the water dockside. Navy maintenance officials noted that the lack of dry docking prevented maintenance in cases where attempting to perform it posed undue risk of water infiltration because the ship was in the water.

According to Navy maintenance officials, the findings during the recent maintenance period demonstrate significant risk for the ship’s ability to continue operating effectively through 2029, especially if the ship does not receive dry dock maintenance, which is not currently planned. The officials noted that, regardless of the potential maintenance that the current test ship may receive in the next few years, continuing to effectively operate it to the end of the decade will be a challenge based on its poor condition.

Uncertain Future for Test Ship Capability

Between 2013 and 2023, the Navy performed or sponsored a series of studies that extensively evaluated options for replacing the current self-defense test ship with another physical test asset. The most recent study, performed by Navy working groups, analyzed a range of options against specific criteria for ship capability. The options included commercial vessels, seven Navy ship classes, and extending the service life of the current test ship. The study did not include analysis of the potential for digital testing to fully replace the current test ship’s capabilities.[47]

Recent Navy action has presented a challenge to replacing the current test ship. Specifically, in October 2024, the Secretary of the Navy directed the Navy to extend the service lives of the five DDG 51 class destroyers that were identified as potential replacements for the current test ship. A senior official from the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations stated that, although the Navy has made no decision on whether it will replace the current test ship, the DDG 51 Flight I destroyers are the best replacement options even if the Navy has to wait for one to be available.

Underlying the lack of a decision on the future for a test ship capability, we found contrasting perspectives on whether the Navy will continue to have a need for the capability provided by the current test ship. For example, Navy acquisition officials told us that they do not currently have a requirement for the use of a self-defense test ship for operational testing beyond fiscal year 2029. However, we found that the Navy’s absence of a formal requirement is not indicative of whether the Navy will have a future need for the test capability provided by the current test ship. Rather, the lack of a requirement is largely due to (1) the Navy expecting to complete remaining tests needed to fulfill existing requirements before the decade’s end, and (2) other programs having yet to progress to where a formal requirement for a test ship could be determined.

In contrast to what Navy acquisition officials told us, operational test and evaluation officials stated that the Navy will continue to need a self-defense test ship capability to support operational testing into the next decade. Specifically, officials from OPTEVFOR and DOT&E cited several reasons for the continuing test ship need:

· The Navy has not demonstrated that it can meet all its operational testing needs for self-defense capability without a remotely controlled test ship.[48] Testing using ships with crew onboard continues to pose unacceptable safety risks, and modeling and simulation continues to need operationally realistic live fire data to validate it.

· As evidenced by recent Red Sea conflicts, the Navy will need to continue to advance—and demonstrate through live testing—the operational capabilities of vessels’ self-defense systems in response to increasingly complex and evolving threats.[49]

· Shipbuilding programs’ history of schedule delays to operational testing suggests that the Navy is likely to have a need for self-defense test ship capability to be available to support current testing requirements beyond fiscal year 2029.

As indicated by OPTEVFOR and DOT&E officials, a gap in, or outright loss of, test ship capability threatens the Navy’s ability to perform the operationally realistic testing needed to sufficiently evaluate ship self-defense systems. Given the implications for broader planning and resourcing that a decision on the future of a test ship capability has, it is critical that key stakeholders from the Navy’s acquisition community, the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, OPTEVFOR, and DOT&E are involved in deciding how best to proceed to meet future test capability needs. These organizations have yet to develop a coordinated plan that reflects a decision.

The Navy risks accepting uncertainty about the adequacy of its operational testing without a clear plan for replacing the current test ship’s capability that is in time to support it in future budgets and, if applicable, considers how to mitigate the effects of any gap in the availability of such capability. Further, the Navy risks being unprepared to effectively respond to new requirements that could emerge for operational testing that necessitate the type of test capability currently provided by the test ship. The lack of a plan also risks eroding the Navy’s ability to evaluate and understand the self-defense capabilities and limitations of its ships, thus passing significant risk to the fleet.

Navy Has Not Taken Action to Transform Its Digital Test Assets and Data

As the state of technology drives rapid advancements in digital capabilities, the Navy has not maximized its opportunities to use digital test assets and data to improve the timeliness and usefulness of operational test and evaluation. As we recently found, DOD and Navy test plans and the DOD Strategic Management Plan identify the need to invest in digital test infrastructure.[50] Additionally, we found that multiple Navy strategies endorsed by senior leadership call for investing in digital assets. For example, the Navy and Marine Corps’ 2020 Digital Systems Engineering Transformation Strategy and the Chief of Naval Operations’ 2024 Navigation Plan call for increased development and use of high-fidelity digital tools and infrastructure that would be useful for testing, among other uses.[51]

The Navy and Marine Corps’ Digital Systems Engineering Transformation Strategy specifically calls out expected next steps. These include developing an accessible authoritative digital source of knowledge, and implementing agile, user-centered approaches to design, develop, test, certify, field, train, and sustain digital capabilities. They also include making institutional changes in requirements, resourcing, and acquisition policy to prioritize digital approaches for Navy acquisition. The Navy’s plans and our prior work demonstrate that tools like digital twins and threads are critical to the future of acquisition and to enabling the Navy to iteratively develop and modify weapons quickly.

While the Navy has yet to take coordinated action to turn plans into results that benefit its shipbuilding enterprise, we found instances of individual Navy organizations investing in digital tools for conducting or understanding operational testing. For example,

· The Navy developed a specific modeling and simulation test asset that required decades of consistent funding and extensive data collection.[52] Navy test officials noted that the fidelity of the model has enabled reductions in the number of live tests needed by at least half, saving millions of dollars. In addition, the officials noted that the usefulness of this digital model has expanded beyond testing to support other Navy interests.

· The Navy supplements air warfare and ship self-defense operational testing with combat system modeling and simulation test beds for its surface vessels like the DDG 51, LHA, and CVN 78 classes. The Navy uses data collected from physical testing by the self-defense test ship, crewed vessels, or both, to validate the interactions in the simulation. These models enable extensive testing of operational performance scenarios that would not be readily achievable through live testing based on cost and other limitations.

Additionally, the Naval Surface Warfare Center, Corona Division developed a dashboard tool, which a senior warfare center official said is intended to make raw operational performance data readily accessible and user-friendly for fleet operators, testers, and other Navy stakeholders. Warfare center officials provided a demonstration of how this digital tool has the potential to be used to assess and communicate operational performance data that could benefit engineers, fleet organizations, and others. Warfare center officials noted that the center funded the tool’s development based on a self-identified need and not in response to an overarching digitalization strategy or plan.

Contrasting with the individual efforts to develop digital test assets, we found challenges with the Navy’s overall efforts to improve the digital infrastructure that supports its operational testing. For example, Navy test officials noted a need for more sustained investment and technology improvements to reduce the need for physical testing.

Navy acquisition officials told us that the lack of digital connectivity among different test facilities across the naval surface warfare centers also creates test inefficiencies. Specifically, they cited cases where, instead of being able to seamlessly use digital connections between systems at the different centers to complete testing, personnel travelled across the country to complete portions of needed testing. Officials said this includes cases where personnel arrived at test facilities only to find that the test assets had not been properly prepared or maintained to support the testing and the activities were canceled, wasting resources and delaying planned testing.

As noted by Navy acquisition and warfare center officials, their lack of access to digital infrastructure has contributed to inefficient test practices, including cases of data loss, repetitive data collection, and shipping physical hard drives as opposed to digitally uploading and transmitting data to a unified digital environment that is accessible to all stakeholders. A warfare center official said that their center spends significant money to keep key data on physical hard drives that are stored in warehouses. While the Navy often shares data, sharing large amounts while maintaining efficiency and fidelity becomes more difficult when the data are not readily accessible through digital infrastructure, such as a digital repository.

Our review found that the Navy does not have a cohesive action plan for investing in and developing digital testing capabilities, including infrastructure improvements to support a common digital source of test information for the shipbuilding enterprise. Such an information source—referred to as a digital thread in our prior work—could improve access to current test data, increasing its usefulness to Navy stakeholders across acquisition, test, and fleet organizations throughout a program’s life cycle.[53]

Officials from seven shipbuilding programs representing a range of surface and undersea vessels told us that they do not have a digital thread to provide an authoritative source of data to help increase data accessibility and coordination and support the full life cycle of a vessel or system. Without such a thread, they instead make program-specific decisions on how to collect and store test data. As an example of this program-specific decision-making, the CVN 78 aircraft carrier program uses a consolidated test database for requirements, test schedule updates, key events tracking, metric evaluation assessments, and other historical test data related to the program. Additionally, the Medium Landing Ship program’s draft TEMP states that the program uses an integrated data environment to store and share test data and other relevant information. As a result of the program-specific approach, a senior Navy warfare center official said that test data are primarily viewed as a consumable, meaning that a program creates models and tools for specific events or to satisfy certain criteria with limited consideration of the value that resulting test data could have beyond fulfilling the program’s specific need.

With each program deciding how to fund and manage its digital test assets and the pursuit of required data, they do not have an incentive to spend more funding to develop enduring assets that provide more capability beyond what fulfills their specific test needs. Specifically, Navy acquisition officials noted that programs do not want to unnecessarily subsidize the continuation of digital test assets for the benefit of other programs, which presents challenges for sustaining modeling and simulation capabilities once the program that initiated it no longer has a need for it. A senior official from the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations told us that having a digital thread as an authoritative source for test data would be beneficial to operational test and evaluation and shipbuilding programs in general. The pursuit of such a digital data source is also consistent with the practices we previously found used by leading commercial companies in product development.[54] These companies continually feed real-time information into a digital thread for a product to support decision-making and iterative processes that enable them to rapidly develop and deploy products.

The Navy’s program-centric approach to acquisitions also impedes the enterprise-wide investments necessary to develop and sustain robust digital tools. OPTEVFOR and DOT&E officials stated that modern and enduring test and evaluation assets are beyond the funding capabilities of individual program offices and require an enterprise resourcing approach. However, the Navy does not have a mechanism for investing in digital assets and infrastructure that can help multiple programs, such as data storage or advanced computational modeling and simulation capabilities. DOT&E officials noted that the Navy’s lack of an enterprise-wide approach to resourcing inhibits the development of enduring digital test assets.

Shipbuilding program officials also noted hesitance to invest in digital test assets in conjunction with other acquisition programs. They stated that relying on another program office to fund part of the development of a system or model puts their program at risk if problems arise with the other program’s ability to fund needed test assets. For example, in 2022, we found that Navy programs did not proactively invest in the digital infrastructure necessary to develop, test, and operate robotic autonomous systems—including autonomous vessels—largely because the Navy does not have the mechanisms it needs to facilitate a coordinated investment plan.[55] We recommended that the Navy provide Congress with a cost estimate that includes the full scope of known costs to develop and operate uncrewed maritime systems, including estimated costs for digital infrastructure. The Navy agreed with the recommendation but has yet to address it.

Without a cohesive implementation plan developed by top Navy leadership that translates the department’s high-level vision and strategy for transforming its digital capabilities, the Navy risks having its various organizations make decisions that focus on meeting narrowly defined needs and overlook opportunities to advance enterprise-wide capabilities. It also risks not having the tools and infrastructure that its strategy says needs to be implemented and maintained to confront an increasingly digital future. The lack of such a plan also strains the Navy’s efforts to perform timely, effective testing of the new vessels that it expects to deliver to the fleet to counter the growing capabilities of its adversaries. Further, without an implementation plan for advancing digital test capabilities, the Navy’s ability to broaden the potential applications of operational test data to support acquisition decision-makers and the warfighters in the fleet will continue to be limited. It also limits the potential for such data to benefit requirements development, design, training, operations, and sustainment of existing and future Navy vessels as sought by its 2020 digital transformation strategy and consistent with leading commercial practices.

Conclusions

The Navy needs to deliver capability to the fleet more quickly than ever if it is to meet the threats of its adversaries. Marginal changes within the existing acquisition structures are unlikely to provide the foundational shift needed to break the pervasive cycle of delays to delivering capabilities needed by the fleet. To more fully pivot toward the future, the Navy needs to make fundamental improvements to address the existing challenges faced by its shipbuilding programs and the fleet. In recent years, the Navy has taken steps to improve its test and evaluation policy and guidance to support a modern strategy for planning and executing operational test and evaluation. This intended strategy focuses on earlier, continuous testing and demonstrating operational capabilities that fulfill the fleet’s missions. However, the Navy has yet to fully integrate operational testing into its acquisition approach in a way that incorporates critical information into the process as early as possible and sets the ship design up for success. Further, the Navy’s test and evaluation policy and associated practices do not require consistent participation in the T&E WIPTs by user representatives from fleet forces organizations who can accept risk on behalf of the fleet and help ensure operational realities are reflected in test plans. This is critical as the Navy endeavors to speed up acquisitions to meet the advancing threats posed by adversaries.

The Navy of the future will continue to need a mix of physical and digital test assets to demonstrate the new capabilities necessary for combating increasingly complex maritime threats. A potential gap or loss of the operational test capability currently provided by the self-defense test ship could result in a significant setback for the Navy’s ability to create highly accurate ship self-defense systems and models that are critical to understanding and confronting those threats. Without a decision about how it will ensure the continued availability of such operational testing capability, the Navy is likely to pass significant risk to the fleet. Further, without a cohesive plan to develop and sustain needed digital test assets and infrastructure for its shipbuilding enterprise, the Navy’s program-centric approach to testing is likely to inhibit investments in enterprise-wide digital capabilities that are critical to the timeliness and usefulness of testing now and especially in the future. The Navy will also be challenged to harness the full potential of digital capabilities to help warfighters effectively operate vessels. The use of such digital capabilities continues to be critical to the Navy’s ability to perform well against its adversaries and defeat future threats.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to the Navy:

The Secretary of the Navy should—in coordination with the Commander, U.S. Fleet Forces Command and Commander, Pacific Fleet—ensure that Navy policy, guidance, and practices provide for consistent participation in the test and evaluation working-level integrated product teams for Navy shipbuilding programs by user representatives from fleet forces organizations. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, and Acquisition—in coordination with the Chief of Naval Operations; Operational Test and Evaluation Force; and Director, Operational Test and Evaluation—makes a decision that outlines the Navy’s plan for maintaining self-defense operational testing capability. This decision should be made in time to support the plan in future budgets and take into account, as applicable, planned actions to mitigate the effect that any gap in test ship availability will have on operational testing and evaluation. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of the Navy should establish a cohesive plan for investing in the development and sustainment of digital infrastructure that will support the Navy’s ability to expand the use of enterprise-wide digital test assets for operational test and evaluation of Navy vessels. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of the controlled unclassified report to the Navy in July 2025 for review and comment. In September 2025, the Navy provided written comments in response to the recommendations, which are reproduced in appendix II. The Navy also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. In its written comments, the Navy concurred with our third recommendation, partially concurred with our second recommendation, and did not concur with our first recommendation.[56]

Regarding our first recommendation, we appreciate the efforts of OPTEVFOR and the Office of the Chief of Naval operations to represent the warfighters’ interests in test planning and execution. However, as we discussed in the report, the Navy’s omission of direct, consistent representation by its fleet organizations in the T&E WIPTs for shipbuilding programs falls short of leading practices that emphasize the importance of user engagement. Specifically, forgoing such direct fleet representation in T&E WIPTs misses opportunities for the user community to help set expectations and inform decisions on test planning and event design for the vessels and associated systems that will eventually be turned over to those users to equip, crew, and operate to fulfill the Navy’s mission. Further, fleet organizations can offer unique and timely tactical insights to operational testing that help ensure decisions on operational realism and relevance of testing reflect the most current threats faced by Navy vessels.