PATIENT PROTECTION AND AFFORDABLE CARE ACT

Preliminary Results of Ongoing Work Suggest Fraud Risks in the Advance Premium Tax Credit Persist

Statement of Seto J. Bagdoyan, Director of Audits, Forensic Audits and Investigative Service

Testimony Before the Subcommittees on the Administrative State, Regulatory Reform, and Antitrust and Oversight, Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 2:00 p.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

A testimony before the Subcommittees on the Administrative State, Regulatory Reform, and Antitrust and Oversight, Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives

For more information, contact: Seto J. Bagdoyan at BagdoyanS@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Preliminary results from GAO’s ongoing covert testing suggest fraud risks in the advance premium tax credit (APTC) persist. The federal Marketplace approved coverage for nearly all of GAO’s fictitious applicants in plan years 2024 and 2025, generally consistent with similar GAO testing in 2014 through 2016. GAO’s covert testing is illustrative and cannot be generalized to the enrollee population.

· Plan year 2024. The federal Marketplace approved subsidized coverage for all four of GAO’s fictitious applicants submitted in October 2024. In total, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) paid about $2,350 per month in APTC in November and December for these fictitious enrollees. For some, the federal Marketplace requested documentation to support Social Security numbers (SSN), citizenship, and reported income. GAO did not provide documentation yet received coverage.

· Plan year 2025. Of 20 fictitious applicants, 18 remain actively covered as of September 2025. APTC for these 18 enrollees totals over $10,000 per month. GAO continues to monitor the enrollments as part of its ongoing work.

More broadly, GAO’s preliminary analyses identified vulnerabilities related to potential SSN misuse and likely unauthorized enrollment changes in federal Marketplace data for plan years 2023 and 2024. Such issues can contribute to APTC that is not reconciled through enrollees’ tax filings to determine the amount of premium tax credit for which enrollees were ultimately eligible. GAO’s preliminary analysis of data from tax year 2023 could not identify evidence of reconciliation for over $21 billion in APTC for enrollees who provided SSNs to the federal Marketplace for plan year 2023. Unreconciled APTC may not necessarily represent overpayments, as enrollees who did not reconcile may have been eligible for the subsidy. However, it may include overpayments for enrollees who were not eligible for APTC.

GAO’s preliminary analyses identified over 29,000 SSNs in plan year 2023 and nearly 68,000 SSNs in plan year 2024 used to receive more than one year’s worth of insurance coverage with APTC in a single plan year. CMS officials explained that the federal Marketplace does not prohibit multiple enrollments per SSN to help ensure that the actual SSN-holder can enroll in insurance coverage in cases of identity theft or data entry errors.

GAO’s preliminary analyses also identified at least 30,000 applications in plan year 2023 and at least 160,000 applications in plan year 2024 that had likely unauthorized changes by agents or brokers. This can result in consumer harm, including loss of access to medications. In July 2024, CMS implemented a new control to prevent such changes, which GAO is reviewing in its ongoing work.

GAO preliminarily identified weaknesses in CMS’s APTC fraud risk management as compared to leading practices. Specifically, CMS has not updated its fraud risk assessment since 2018 despite changes in the program and its controls. Further, CMS’s 2018 assessment may not fully align with leading practices, like identifying inherent fraud risks. Finally, CMS did not use its 2018 assessment to develop an antifraud strategy. Together, these weaknesses appear to hinder CMS’s ability to effectively and proactively manage fraud risks in APTC.

Why GAO Did This Study

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act provides premium tax credits to help eligible individuals pay for health insurance. The federal government can pay this credit directly to health insurance issuers as APTC. CMS estimated that it paid nearly $124 billion in APTC for about 19.5 million enrollees in plan year 2024. Consumers can enroll in insurance through the federal Marketplace independently or with assistance from an agent or broker.

Recent indictments highlight concerns about agent and broker practices in the federal Marketplace. Further, CMS reported that it received roughly 275,000 complaints in 2024 that consumers were enrolled or had insurance plans changed in the federal Marketplace without their consent.

This testimony discusses preliminary results of ongoing GAO work related to (1) covert testing and (2) data analyses of enrollment controls in the federal Marketplace, as well as (3) CMS’s APTC fraud risk assessment and antifraud strategy.

To perform this work, GAO created 20 fictitious identities and submitted applications for health care coverage in the federal Marketplace for plan years 2024 and 2025. The results, while illustrative, cannot be generalized to the full enrollment population. Additionally, GAO analyzed federal Marketplace enrollment data for plan years 2023 and 2024 and compared these data to federal death data and tax data. Finally, GAO assessed documentation related to CMS’s fraud risk management activities against relevant leading practices.

What GAO Recommends

GAO’s work is ongoing, and it will consider recommendations as part of future products, as appropriate.

Chairmen Fitzgerald and Van Drew, Ranking Members Nadler and Crockett, and Members of the Subcommittees:

I am pleased to appear before you today to discuss preliminary results from selected aspects of our ongoing work related to fraud risk management in the advance premium tax credit (APTC). We recently issued a report summarizing preliminary results from this ongoing work.[1] As a result, the information I present today is subject to that ongoing work and subsequent review and revision.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) provides premium tax credits to those who purchase private health insurance plans and meet certain income and other requirements.[2] Individuals may have the federal government pay this credit to their health insurance issuers in advance on their behalf, known as APTC, which lowers their monthly premium payments.

Millions of consumers have purchased health insurance plans through the marketplaces established under PPACA. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), is responsible for maintaining the federal Marketplace and overseeing state-based marketplaces. Under PPACA, states may elect to operate their own state-based marketplace or to use the federal Marketplace. These marketplaces determine eligibility for APTC, based in part on income, and allow individuals to compare and choose among insurance plans offered by participating private health care coverage issuers. CMS estimated it paid nearly $124 billion in APTC for about 19.5 million enrollees for plan year 2024.[3]

Consumers can enroll in health insurance coverage through a marketplace independently or with assistance, such as from an insurance agent or broker. As discussed later in this statement, agents and brokers can help a consumer apply for coverage, including for related financial assistance, and enroll in a plan. Assistance from an agent or broker is of no cost to a consumer. Rather, agents and brokers are allowed to receive compensation directly from health insurance issuers in accordance with agreements with those issuers and any applicable state requirements.

Indictments from December 2024 and February 2025 highlight concerns about agent and broker practices in the federal Marketplace. Specifically, the indictments allege that bad actors enrolled consumers in insurance through the federal Marketplace by falsifying information on their applications. Additionally, according to CMS, the agency received approximately 275,000 complaints between January and August 2024 that consumers were enrolled in a plan or had their plan changed without their consent. Such practices can result in wasteful federal spending on APTC for enrollees who are not eligible. Further, such practices can result in harm and unexpected costs for consumers. These can include loss of access to medical providers and medications, higher copayments and deductibles, or repayment of APTC if income or other eligibility was misrepresented.

We previously reported that APTC is at risk of fraud.[4] For example, in September 2016, we found that federal and state marketplaces approved coverage for our fictitious applicants.[5] Nearly all of these fictitious applicants remained covered after we sent fictitious documents or no documents to resolve issues with our applications. Further, in July 2017, we found that CMS did not design processes to verify eligibility for APTC, including preventing duplicate coverage.[6]

My statement today is based on a recent report we issued that summarizes preliminary results and analyses from ongoing work related to fraud risk management in APTC.[7] Specifically, this statement addresses preliminary results from our:

1. covert testing of federal Marketplace enrollment controls for plan years 2024 and 2025,

2. analyses of federal Marketplace enrollment data for plan years 2023 and 2024, and

3. evaluation of CMS’s fraud risk assessment and antifraud strategy for APTC.

To perform covert testing of federal Marketplace enrollment controls, we created 20 fictitious identities and submitted applications for individual health care coverage in the federal Marketplace. We submitted applications for four of these fictitious identities in October 2024 for coverage through December 2024, which was the remainder of that plan year. We pursued coverage for plan year 2025 for all 20 fictitious identities, including the four identities for which we already submitted applications. Our covert testing for plan year 2025 is ongoing, since the plan year is not yet complete. As a result, we will describe additional details of the 2025 applications in a future report.

Our covert testing included applications submitted independently through HealthCare.gov, which is the federal Marketplace’s website, and applications submitted with assistance from an insurance agent or broker. For all our applicant scenarios, we sought to act as an ordinary consumer would in attempting to make a successful application. For example, if, during online applications, we were directed to make phone calls to complete the process, we acted as instructed.

For applications for plan year 2024, our covert tests included fictitious applicants who provided invalid (i.e., never issued) Social Security numbers (SSN). Additionally, we stated income at a level eligible to obtain APTC.[8] As appropriate, we used publicly available information to construct our applications for coverage and subsidies. We also used publicly available hardware, software, and materials to produce counterfeit documents that we submitted, if appropriate for our testing, when instructed to do so. We then observed the outcomes of the document submissions, such as any approvals received or requests to provide additional supporting documentation. The results of our covert testing, while illustrative of potential enrollment control weaknesses, cannot be generalized to the overall enrollment population.

To examine federal Marketplace enrollment for plan years 2023 and 2024, we obtained and analyzed federal Marketplace enrollment and payment data, including APTC information, from CMS. We also matched enrollee SSNs in the data to two additional data sources: (1) Social Security Administration’s (SSA) full death file, a database containing records of death that have been reported to SSA, as of November 2024 and (2) April 2025 data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) on APTC reconciliation from tax forms filed for tax year 2023.[9] We assessed the reliability of all data sets by performing electronic tests to determine the completeness and accuracy of key fields. We also reviewed agency documentation and interviewed knowledgeable agency officials about the reliability of the data. Overall, we found that the data were reliable for our purposes.

To examine CMS’s fraud risk assessment and antifraud strategy for APTC, we reviewed documentation of CMS’s policies and fraud risk management activities related to APTC. This included CMS’s 2018 fraud risk assessment for APTC. Additionally, we interviewed agency officials about CMS’s fraud risk management activities in this program. We reviewed relevant reports from GAO and HHS’s Office of the Inspector General. We evaluated information from relevant documentation and interviews of agency officials against relevant leading practices in GAO’s A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (Fraud Risk Framework).[10]

To support all three objectives, we interviewed CMS officials and representatives from seven stakeholder organizations that represent agents and brokers, state insurance regulators, researchers, and one of the entities that CMS approved to host a non-marketplace website where consumers can apply for and enroll in a plan offered through the federal Marketplace.

The ongoing work upon which this statement is based is being conducted in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our preliminary findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Additionally, our related investigative work is being conducted in accordance with standards prescribed by the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency.

Background

APTC Eligibility and Enrollment Processes

APTC Eligibility

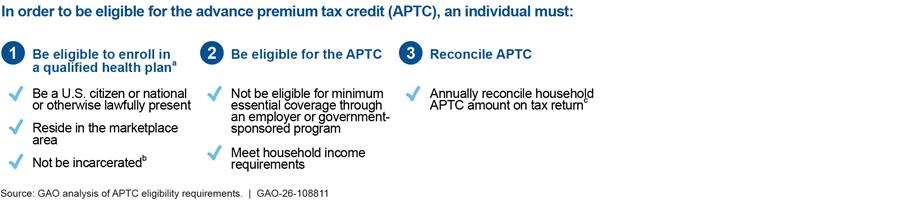

To qualify for a premium tax credit, individuals must be enrolled in a qualified health plan offered through a marketplace and meet certain criteria. These tax credits can be paid in advance through APTC.[11] See figure 1 for the APTC eligibility requirements.

Figure 1: Eligibility Requirements for the Advance Premium Tax Credit

aTo apply and qualify for the APTC, an individual must first be enrolled in a qualified health plan offered through the individual’s respective marketplace. The eligibility requirements shown above only reflect those that pertain to an individual applying during the open enrollment period, as there may be additional requirements during special enrollment periods.

bAn incarcerated individual who is awaiting disposition of charges is eligible for a qualified health plan.

cTax return reconciliation is completed for the household of the individual receiving advance payments toward insurance premiums.

The amount of the premium tax credit varies based on household income and the cost of a benchmark plan.[12] The credit limits what the consumer would pay for that plan to be no more than a certain percentage of their household income. The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 made temporary changes to premium tax credits by expanding eligibility to higher-income individuals and increasing premium tax credits for lower-income individuals for tax years 2021 and 2022.[13] For example, the law increased the premium tax credit amounts for eligible individuals and families, resulting in access to plans with no premium contributions for those earning 100 to 150 percent of the federal poverty level. It also expanded eligibility for premium tax credits to include certain individuals and families with incomes at or above 400 percent of the federal poverty level. Public Law 117-169—commonly known as the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022—extended these provisions through the end of tax year 2025.[14] See table 1.

Table 1: Maximum Percentage of Household Income Paid for Premiums of the Benchmark Plan, by Federal Poverty Level, 2020 and 2025

|

Percent of federal poverty level |

Maximum percentage of annual household income paid for premiums of the benchmark plan, 2020 |

Temporary maximum percentage of annual household income paid for premiums of the benchmark plan, 2025a |

|

At least 100 up to 150b |

2.07 – 4.14 |

0.0 |

|

At least 150 up to 200 |

4.14 – 6.52 |

0.0 – 2.0 |

|

At least 200 up to 250 |

6.52 – 8.33 |

2.0 – 4.0 |

|

At least 250 up to 300 |

8.33 – 9.83 |

4.0 – 6.0 |

|

At least 300 up to 400 |

9.83 |

6.0 – 8.5 |

|

At least 400 and higher |

100 |

8.5 |

Source: GAO analysis Department of Health and Human Services data. | GAO‑26‑108811

Note: The cost of a benchmark plan varies based on factors including the consumer’s age and location.

aThese percentages are temporary. The temporary percentages were established in 2021 and extended through 2025. American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Pub. L. No. 117-2, § 9661, 135 Stat. 4, 182 and An Act To provide for reconciliation pursuant to title II of S. Con. Res. 14, Pub. L. No. 117-169, § 12001, 136 Stat. 1818, 1905 (2022).

bPremium tax credits are generally only available to households with incomes at or above 100 percent of the federal poverty level. Lawfully present immigrants with incomes less than 100 percent of the federal poverty level may receive premium tax credits if they are ineligible for Medicaid based on immigration status. Public Law No. 119-21—commonly known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act—repealed this eligibility applicable to tax years beginning after December 31, 2025. An Act To provide for reconciliation pursuant to title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Pub. L. No. 119-21, title VII, § 71302, 139 Stat. 72, 322 (2025).

In 2013, CMS developed the Data Services Hub (Hub) to help verify applicant eligibility in an automated manner. To do so, the Hub matches applicant information, such as SSN and estimated income, against trusted data sources. These sources include records from SSA and IRS. In the federal Marketplace, the system generates an inconsistency when data matching processes are not able to verify applicant information against the Hub’s trusted sources. When an inconsistency is generated, applicants are instructed to provide documentation to support information on their applications that cannot be verified by the Hub’s data matching.

Marketplaces and Enrollment Pathways

States, along with the District of Columbia, may elect to rely on the federal Marketplace or operate their own health insurance marketplace. Table 2 describes the types of health insurance marketplaces.

Table 2: Types of Health Insurance Marketplaces

|

Platform |

Description |

States using each platform in plan year 2025 |

|

Federal Marketplace |

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) operates the federal Marketplace’s website, HealthCare.gov. Consumers in states that operate on the federal Marketplace apply for and enroll in coverage through HealthCare.gov. Consumers can also apply and enroll in coverage through federally approved non-marketplace websites. |

28 |

|

State-based Marketplace |

With approval from CMS, states can choose to operate marketplaces with their own eligibility and enrollment platforms. Consumers in these states apply for and enroll in coverage through marketplace websites established and maintained by the states. Consumers can also apply for and enroll in coverage through state-approved non-marketplace websites. |

20 |

|

State-based Marketplace on the Federal Platform |

States can choose to operate their own marketplace to perform certain core functions and rely on the federal platform to perform eligibility and enrollment functions. |

3 |

Source: GAO analysis of CMS information. | GAO‑26‑108811

Note: This table includes the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

The federal Marketplace offers multiple pathways to enroll in health insurance coverage and receive APTC. Consumers in states that use the federal Marketplace may enroll in coverage through the pathway known as HealthCare.gov or an enhanced direct enrollment (EDE) pathway, among others. Table 3 describes examples of enrollment pathways in the federal Marketplace.

Table 3: Examples of Enrollment Pathways in the Federal Marketplace

|

Pathway |

Description |

|

Marketplace |

The consumer may apply for and enroll in health insurance coverage through the federal Marketplace website, HealthCare.gov. |

|

Direct enrollment |

The consumer may use a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) approved, non-marketplace website to apply for and enroll in health insurance coverage. However, the consumer is directed to HealthCare.gov to complete the eligibility application before enrolling in health coverage. CMS announced plans to end this pathway starting November 1, 2025. |

|

Enhanced direct enrollment |

The consumer may use a CMS-approved, non-marketplace website to apply for and enroll in health insurance coverage without being redirected to HealthCare.gov. |

Source: GAO analysis of CMS information. | GAO‑26‑108811

Note: Additional pathways may include applications submitted via paper or telephone.

Role of Agents and Brokers

Consumers seeking to obtain health insurance through the federal Marketplace may receive assistance from agents and brokers who help them apply for coverage, including related financial assistance, and enroll in a health plan.[15] In return, agents and brokers receive payment (commissions or salaries) from the issuers of the health plans. Agents and brokers must be licensed in the state in which they sell plans and registered with CMS to sell plans through the federal Marketplace.[16] According to CMS, most enrollments in the federal Marketplace are assisted by an agent or broker through the EDE and direct enrollment pathways.

CMS is responsible for oversight of agents and brokers in the federal Marketplace and ensuring that they comply with federal rules. Agents and brokers are required to, among other things, obtain and document consumers’ consent before assisting them with applying for and enrolling in coverage through the federal Marketplace.[17] For example, consumer consent is required before the agent or broker can:

· collect or use any personally identifiable information, such as name, date of birth, and SSN;

· help a consumer apply for coverage or financial assistance by completing an eligibility application on their behalf; and

· actively enroll a consumer in a plan offered through the federal Marketplace.

After a consumer has applied or is enrolled, the agent or broker can also update a consumer’s eligibility application or plan selection on their behalf, if the initial consent authorized the agent or broker to do so, or if they obtained subsequent consent for any new actions. Agents and brokers are required to make documentation of consumer consent available to CMS upon request in response to monitoring, audit, and enforcement actions.

Fraud Risk Management

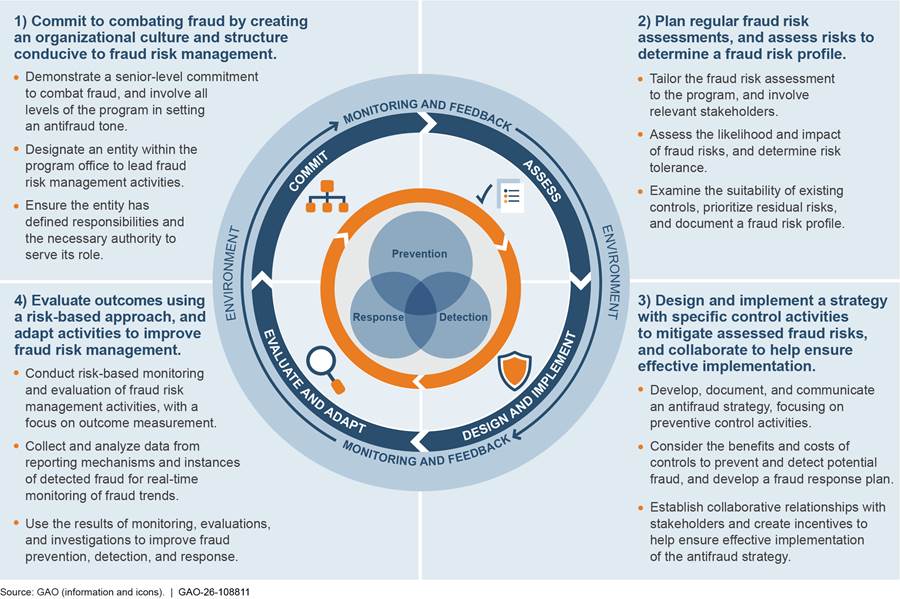

The objective of fraud risk management is to ensure program integrity by continuously and strategically mitigating both the likelihood and effects of fraud, while also facilitating a program’s mission. The Fraud Risk Framework provides a comprehensive set of leading practices that serve as a guide for agency managers to use when developing efforts to combat fraud in a strategic, risk-based manner. As depicted in figure 2, the framework organizes the leading practices within four components: (1) Commit, (2) Assess, (3) Design and Implement, and (4) Evaluate and Adapt.

Figure 2: Overview of the Fraud Risk Framework

In June 2016, the Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015 (FRDAA) required the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to establish guidelines for federal agencies to create controls to identify and assess fraud risks to design and implement antifraud control activities. The act further required OMB to incorporate the leading practices from the Fraud Risk Framework in the guidelines.[18] The Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 repealed FRDAA but maintained the requirement for OMB to provide guidelines to agencies in implementing the Fraud Risk Framework.[19]

In its 2016 Circular No. A-123 guidelines, OMB directed agencies to adhere to the Fraud Risk Framework’s leading practices.[20] In October 2022, OMB issued a Controller Alert reminding agencies that they must establish financial and administrative controls to identify and assess fraud risks.[21] In addition, the alert reminded agencies that they should adhere to the leading practices in the Fraud Risk Framework as part of their efforts to effectively design, implement, and operate an internal control system that addresses fraud risks.

The Federal Marketplace Approved Subsidized Coverage for Nearly All of Our Fictitious Applicants in Plan Years 2024 and 2025, Suggesting Weaknesses Persist

Our covert testing of enrollment controls in the federal Marketplace suggests weaknesses have persisted since our tests in plan years 2015 through 2016. All four of our fictitious applications received subsidized coverage through the federal Marketplace in late 2024. Additionally, although our work is ongoing, as of September 2025 18 of our 20 fictitious applications for plan year 2025 were receiving subsidized coverage. We will continue to monitor the status of these applications during plan year 2025.

All Four of Our Fictitious Applicants Received Subsidized Coverage in Late 2024

To test enrollment controls, we developed and submitted four fictitious applications to obtain insurance coverage with APTC through the federal Marketplace. We applied for coverage for these four applicants in October 2024. We submitted the applications outside of the open enrollment period, using a special enrollment period for low-income applicants.[22] In two cases, we applied for coverage directly through HealthCare.gov. In the other two cases, we applied via telephone with assistance from an insurance broker.[23] The brokers that assisted us used EDE systems to submit our applications.

The federal Marketplace approved fully subsidized insurance coverage for all four of our fictitious applicants for November through December 2024. The combined total amount of APTC paid to insurance companies for all four fictitious enrollees was about $2,350 per month. While our fictitious enrollees are not generalizable to the universe of enrollees, they suggest weaknesses in enrollment controls—such as identity proofing and income verification—in the federal Marketplace through both HealthCare.gov and EDE systems.[24] Table 4 summarizes the results of our covert testing of enrollment controls for plan year 2024.

Table 4: Results of GAO’s Covert Testing of Enrollment Controls in the Federal Marketplace in Late 2024

|

Case |

Route |

Identify proofing |

Documentation supporting eligibility |

Enrolled and APTC Paid |

||

|

Requested by Marketplace |

Submitted by GAO |

Accepted by Marketplace |

||||

|

1 |

HealthCare.gov |

Completed with fictitious documentation |

Income |

None |

N/A |

Yes |

|

Citizenship |

None |

N/A |

||||

|

2 |

HealthCare.gov |

Completed with fictitious documentation |

None |

N/A |

N/A |

Yes |

|

3 |

Broker from HealthCare.gov |

Not requesteda |

Social Security number (SSN) |

None |

N/A |

Yes |

|

Income |

None |

N/A |

||||

|

Citizenship |

Fictitiousb |

Yesb |

||||

|

4 |

Broker from Advertisement |

Not requesteda |

SSN |

None |

N/A |

Yes |

|

Income |

None |

Yesc |

||||

|

Citizenship |

None |

N/A |

||||

Legend: APTC = Advance premium tax credit; N/A = Not applicable.

Source: GAO. | GAO‑26‑108811

aIn these cases, our fictitious applicants worked with agents or brokers and the Marketplace Call Center to submit applications with invalid SSNs. However, we were not prompted to provide documentation to verify our applicant’s identity in either case.

bWe submitted fictitious documentation to support citizenship for this applicant’s 2025 enrollment in December 2024. The Marketplace notified us that it verified our applicant’s citizenship using the documentation, which also applied to the applicant’s 2024 enrollment.

cThe Marketplace notified us that it had verified the applicant’s estimated income based on documentation we submitted. However, we did not submit documentation to support the applicant’s income.

The results of our covert testing for plan year 2024 are generally consistent with results of similar testing we conducted for plan years 2014 through 2016.[25]

Identity Proofing

The federal Marketplace requires applicants to verify their identity before enrolling in insurance coverage. For both of our 2024 applications through HealthCare.gov, our fictitious applicants initially failed the online identity proofing step, as expected.[26] However, we were later cleared by the federal Marketplace to submit our applications after we submitted fictitious identification documents.

Similarly, per CMS guidelines, EDE entities must require that agents and brokers who assist consumers complete identity proofing for the consumer.[27] For our two broker-assisted applications—which used EDE systems—we were not requested to submit documentation to verify our applicants’ identity before enrolling. However, the systems used by the brokers assisting our applicants flagged our applicants’ SSNs as unverified. In October 2024, CMS began requiring verifiable SSNs on applications submitted by agents and brokers through EDE systems.[28] In both cases, the brokers assisting our applicants called the Marketplace Call Center to address the issue. During the calls, our fictitious applicants authorized their brokers to discuss the applications with the Marketplace Call Center without the applicants present on the call. Both brokers worked with the Marketplace Call Center—without the applicants—to successfully submit the applications with invalid SSNs.

Data Matching Inconsistencies

As described earlier, the federal Marketplace uses the Hub to help verify applicant eligibility—such as citizenship and estimated income—in an automated manner against trusted data sources. The federal Marketplace generates an inconsistency when data matching processes are not able to verify applicant information against the Hub’s trusted sources. Applicants are instructed to provide documentation to support information on their applications that cannot be verified by the Hub’s data matching.

However, the federal Marketplace did not always generate data matching inconsistencies across our four fictitious applicants. Specifically,

· in one case, the Marketplace did not request documentation to corroborate the applicant’s citizenship status or estimated income.

· in a different case, the Marketplace did not request documentation to support the applicant’s SSN.

· in the remaining two cases, the Marketplace requested documentation to support each applicant’s SSN, citizenship status, and estimated income, as expected.

We either were not requested to provide the federal Marketplace with documentation or generally did not provide what was requested, yet our four fictitious applicants received subsidized coverage for November and December 2024.[29] Because we applied for coverage late in the year, the due dates for the requested documentation to support our applicants’ eligibility all fell after the end of the plan year. In one case, we received a notice from the federal Marketplace that it confirmed the applicant’s estimated income based on documentation we submitted. However, we did not submit documentation to confirm the applicant’s income. Such weaknesses in appropriately generating and resolving data matching inconsistencies may allow ineligible applicants to receive subsidized insurance coverage.

Eighteen of Our 20 Fictitious Applicants Continued to Receive Subsidized Coverage for Plan Year 2025

To further test enrollment controls, we developed 20 fictitious applications to obtain insurance coverage with APTC through the federal Marketplace for plan year 2025.[30] Although our work is ongoing, the federal Marketplace initially approved coverage for 19 of our 20 fictitious applicants for plan year 2025. We did not pursue one application when the broker we were working with stopped responding to us. Additionally, the Marketplace subsequently cancelled coverage for one fictitious enrollee for which we did not provide the requested documentation to support citizenship status. As a result, as of September 2025, coverage for 18 fictitious enrollees remained active. The results of our covert testing for plan year 2025 are generally consistent with results of similar testing we conducted for plan years 2014 through 2016.[31]

The combined APTC paid to insurance companies for these 18 enrollees totals over $10,000 per month. While these fictitious enrollees are not generalizable to the universe of enrollees, they can suggest weaknesses in enrollment controls. We will continue to respond to any future documentation requests from the federal Marketplace and monitor related developments in these enrollments as part of our ongoing work.

Preliminary Results Identify Vulnerabilities Related to Potential SSN Misuse and Unauthorized Enrollment Changes

Preliminary Data-Analytics Results Identify Potential SSN Misuse in Plan Years 2023 and 2024

Consumers who choose to have the credit paid through the APTC must reconcile the amount of APTC paid to issuers on their behalf with the premium tax credit they were ultimately eligible for based on actual family sizes and incomes reported when those consumers file their federal income tax returns. During this reconciliation process, the consumer may receive an additional tax credit or may be responsible for repaying the excess APTC amount paid to an issuer. Federal law may limit the amount of excess APTC that consumers must repay.[32]

SSNs—which should serve as unique identifiers for enrollees that have them—are important for reconciling APTC on individual federal income taxes.[33] We compared enrollment data in the federal Marketplace for plan year 2023 to APTC reconciliation data for tax year 2023.[34] Based on our preliminary analysis, we could not identify evidence of reconciliation in IRS tax data, as of April 2025, for over $21 billion in APTC for enrollees that provided an SSN through the federal Marketplace in plan year 2023.[35] This represents approximately 32 percent of APTC paid on behalf of enrollees that provided an SSN to the federal Marketplace for that plan year.

Unreconciled APTC does not necessarily represent overpayments, as enrollees who did not reconcile through tax filing may have been eligible for APTC. However, it may include overpayments for enrollees who were ultimately not eligible for APTC.[36] There are various reasons why consumers might not reconcile APTC, including households that do not file tax returns as required and misuse of SSNs in Marketplace applications.[37] Our preliminary analyses of federal Marketplace enrollment data identified issues with potential misuse of SSNs, including multiple uses of SSNs and those that match death data.

Overused SSNs

One issue that can hinder reconciliation of APTC through tax filing is use of an SSN that does not belong to the enrollee. Our preliminary analysis of federal Marketplace data identified over 29,000 SSNs (0.21 percent of SSNs that received APTC) with more than 365 days of insurance coverage with APTC in plan year 2023. For example, the most frequently used SSN in plan year 2023 was used to receive subsidized insurance coverage for over 26,000 days (over 71 years of coverage) across over 125 insurance policies. Further, our preliminary analysis identified nearly 66,000 SSNs (0.37 percent of SSNs that received APTC) with more than 366 days of insurance coverage with APTC in plan year 2024.[38] This overuse can occur because of identity theft and synthetic identity fraud, as well as data entry errors.[39] Given complexities around identifying the true SSN-holder, we are further examining these cases and other instances of apparently overlapping coverage as part of our ongoing work.

According to CMS officials, the federal Marketplace does not prohibit new enrollments that use an SSN that is already enrolled. They further explained this is done to help ensure that the actual SSN-holder can enroll in insurance coverage in cases of identity theft or data entry errors. These officials told us that the federal Marketplace uses a logic model that analyzes various elements of personally identifiable information to distinguish individual applicants and enrollees. They added that they apply this model on a monthly basis to deduplicate enrollments. Further, applications with SSNs already enrolled should be addressed through CMS’s existing data matching inconsistency processes, where applicants provide documentation to support application information that could not be originally verified.

For example, enrollees with these overused SSNs should be identified through CMS’s existing data matching inconsistency processes and required to submit documentation to substantiate their SSNs. This is because multiple identities with different personally identifiable information will not match SSA records for the same SSN. However, our analyses and identification of enrollments with these overused SSNs suggests that the data matching inconsistency processes may not always function as expected. We are reviewing the federal Marketplace’s data matching inconsistency processes, including overused SSNs, as part of our ongoing work.

Death Data Matches

Another issue that can hinder reconciliation of APTC is use of an SSN that is reported as associated with a deceased individual in SSA death data. Such cases can include benefits for deceased individuals and fictitious or synthetic identities. Our preliminary analysis of plan year 2023 data identified over 58,000 SSNs that received APTC and matched SSA death data (about 0.42 percent of SSNs that received APTC that year).[40]

Because of complexities in determining APTC paid after the reported date of death, we focused our review of death data matches on two scenarios for this statement, which account for about 26,000 of the 58,000 SSNs we identified as matching the death data.[41] Based on our preliminary analyses, we found that CMS paid over $94 million in APTC for households with at least one match across these two scenarios for plan year 2023.[42]

· First, we identified over 7,000 SSNs where the reported date of death occurred prior to enrollment in the Marketplace for plan year 2023.[43] In these cases, Marketplace data matched SSA death data on (1) SSN and (2) first name, last name, or birth month and year.

· Second, we identified over 19,000 SSNs that matched death data only on SSN. In these cases, matches had different names and dates of birth across Marketplace enrollment data and SSA’s death data. These matches could represent synthetic identity fraud.

Although CMS has processes to review death data during enrollment, the agency does not periodically review death data for all federal Marketplace enrollees. As part of our ongoing work, CMS officials told us that the federal Marketplace checks death status at application through the Hub and twice a year through periodic data matching. However, CMS officials explained that the periodic data matching process only ends coverage for single-member households in which the enrollee is deceased, and it does not end coverage for deceased individuals in households with multiple members. CMS expects households to report member changes, including death, to the Marketplace. We are examining CMS’s controls regarding review of death data as part of our ongoing work.

Preliminary Data-Analytics Results Identify Likely Unauthorized Enrollment Changes by Agents and Brokers in Plan Years 2023 and 2024, Although CMS Has Taken Some Corrective Steps

The federal Marketplace does not pay commissions to agents or brokers or set their compensation levels. Rather, agents and brokers are allowed to receive compensation directly from qualified health plan issuers in accordance with agreements with those issuers and any applicable state requirements. The federal Marketplace transmits information identifying agents and brokers associated with enrollments to insurance companies to facilitate compensation per these agreements. As a result, agents and brokers have a financial incentive to maximize enrollments and their related compensation. Beyond legitimate enrollments, this may include making unauthorized changes to existing enrollments, enrolling consumers without their knowledge or consent, and creating fictitious enrollments.

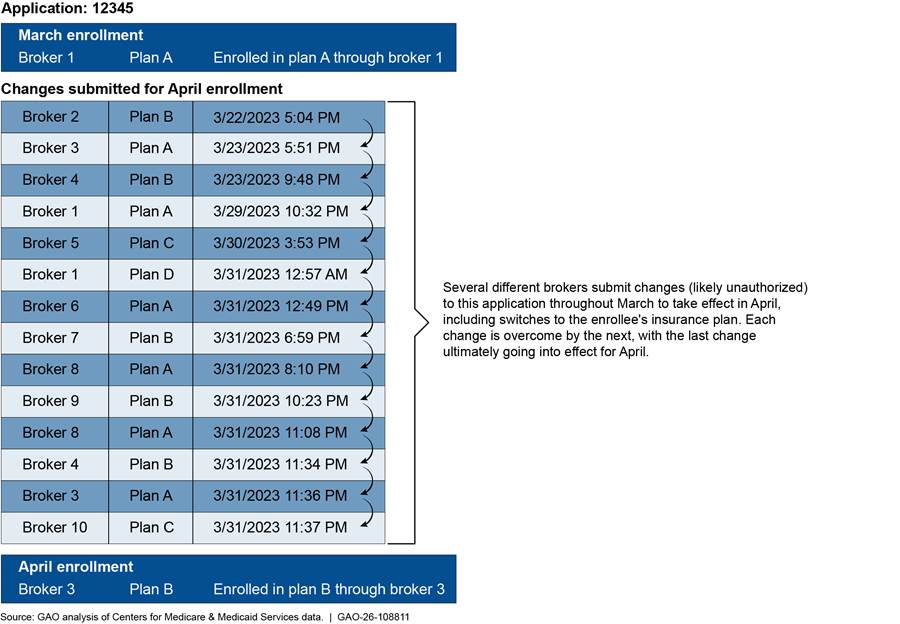

For this statement, we focused our analyses on enrollment changes that involve changes in the agent or broker associated with an enrollment (and may include other changes, such as in an insurance plan).[44] Changes in the agent or broker associated with a consumer’s enrollment may be directed by the consumer. Other changes may be driven by factors outside of the consumer’s control, such as when agents and brokers retire and sell their business to other agents or brokers. For the purposes of this statement, an application with likely unauthorized enrollment changes is one where at least three different agents or brokers—identified based on National Producer Numbers—submitted enrollment actions on the same application for the same coverage start date.[45]

Figure 3 illustrates an actual, though anonymized, example of likely unauthorized enrollment changes for one application we identified through our analyses. This application in the federal Marketplace had coverage in March 2023. Several different brokers submitted likely unauthorized changes to this application to take effect in April 2023, including changes to the enrollee’s insurance plan. We cannot determine why brokers made these changes to the enrollee’s insurance plan based on the enrollment data. However, we believe that they are likely unauthorized because it is unlikely that an enrollee would work with more than two different agents and brokers to select different insurance plans, especially with changes on the same day or within the same hour.

Figure 3: Anonymized Example of Application with Likely Unauthorized Enrollment Changes in the Federal Marketplace

Note: We cannot determine why brokers made changes to the enrollee’s insurance plan based on the enrollment data.

Based on our preliminary analyses, we identified at least 30,000 applications in plan year 2023 and at least 160,000 applications in plan year 2024 that had likely unauthorized changes.[46] This represents 0.4 percent of relevant applications in plan year 2023 and 1.5 percent of relevant applications in plan year 2024. While only one enrollment change may go into effect for a given month, the volume of these actions indicates potential misconduct by agents and brokers seeking to maximize commissions related to federal Marketplace enrollments.

Stakeholders we interviewed as part of our ongoing work, including those that represent agents, brokers, and insurance regulators, raised concerns that consumers may not have been aware of changes to their enrollment because of a lack of notification about agent and broker activities at the time the unauthorized activity occurred. For example, they said consumers may have learned they were enrolled in a plan when they received a notice from the IRS during tax filing season advising them to reconcile their APTC or when they sought medical care and learned that their plan had been switched.

In July 2024, CMS began blocking changes to enrollments by agents and brokers who were not already associated with the consumer’s enrollment. To change the agent or broker associated with an enrollment, CMS required that consumers conduct a three-way call with the Marketplace Call Center and the new agent or broker.[47]

Stakeholders we interviewed questioned the effectiveness of the three-way calls to prevent unauthorized agent and broker activity. For example, they explained that the Marketplace Call Center may take limited steps to verify the identity of the consumer on the three-way call. This may involve asking the consumer for information that may be publicly available, like name and date of birth. According to CMS officials, the Marketplace Call Center validates three pieces of personally identifiable information about the consumer. Additionally, enrollments for new coverage may not trigger the requirement for a three-way call with the Marketplace Call Center. Agents and brokers seeking to maximize enrollments could submit new applications in these cases, thus circumventing the three-way call process. We are examining the three-way call process as part of our ongoing work.

In October 2024, CMS issued a press release stating that it had received over 90,000 complaints between January and August 2024 from consumers who had their federal Marketplace insurance plans changed without their consent.[48] CMS further stated that it had resolved nearly all of the complaints and that the number of plan changes associated with an agent or broker decreased by nearly 70 percent. CMS also suspended 850 agents and brokers from the federal Marketplace for reasonable suspicion of fraudulent or abusive conduct related to unauthorized enrollments or unauthorized plan switches. However, in May 2025, CMS officials told us that the agency reinstated all these suspended agents and brokers to better fulfill the agency’s statutory and regulatory procedures. According to agency officials, CMS continues to monitor agent and broker activity for compliance with Marketplace regulations and the terms and conditions of Marketplace agreements and may take further enforcement action against those individuals.

Preliminary Results Indicate Weaknesses in CMS’s Fraud Risk Management for APTC

Preliminary results from our ongoing work indicate weaknesses in CMS’s fraud risk management in APTC. Specifically, although CMS assessed APTC’s fraud risks in 2018, the agency has not updated its assessment despite changes in the program and its antifraud controls. Further, CMS’s 2018 assessment may not fully align with leading practices. Finally, CMS did not use its assessment to develop an antifraud strategy to address the risks it assessed. Together, these weaknesses appear to hinder CMS’s ability to effectively and proactively manage fraud risks in APTC.

CMS Assessed Fraud Risks in 2018 but Has Not Updated Its Assessment Despite Program Changes

CMS conducted a fraud risk assessment for APTC in November 2018 in response to a GAO recommendation.[49] However, CMS has not updated its fraud risk assessment for APTC since then despite changes to the program. CMS’s 2018 assessment acknowledged that fraud risks in APTC are continually evolving. In addition to evolving fraud risks, program changes affect the likelihood and impact of fraud risks in the program, as well as the controls the agency uses to mitigate those risks. For example:

· Program growth. Estimated APTC has more than doubled since CMS’s 2018 fraud risk assessment. Specifically, CMS estimated that APTC totaled over $53 billion in 2018. In 2024, CMS estimated that APTC totaled nearly $124 billion. Additional outlays may increase the likelihood or impact of fraud risks and potentially warrant additional or different antifraud controls.

· Changes to antifraud controls. CMS officials told us that the agency paused certain antifraud controls since the 2018 fraud risk assessment. For example, CMS did not act on IRS data for consumers who did not file tax returns and reconcile prior APTC for plan years 2021 through 2024.[50] Conversely, CMS has implemented new antifraud controls—such as requiring verifiable SSNs on applications submitted through EDE systems—since its 2018 fraud risk assessment. Changes to antifraud controls—such as pausing existing controls or adding new controls—may affect the likelihood and impact of fraud risks.

Leading practices in fraud risk management call for planning regular fraud risk assessments that are tailored to programs. For example, leading practices include planning to conduct fraud risk assessments at regular intervals.[51] They also call for assessments when there are changes to the program or operating environment, as assessing fraud risks is an iterative process.

As part of our ongoing work, CMS officials informed us that the agency plans to update its fraud risk assessment for APTC by the end of calendar year 2025. We will continue to monitor CMS’s efforts to complete this assessment.

CMS’s 2018 Fraud Risk Assessment May Not Have Fully Met Leading Practices

Although our work is ongoing, preliminary results suggest that CMS’s 2018 fraud risk assessment for APTC may not fully align with leading practices in GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework. Such weaknesses may hinder CMS’s ability to effectively and proactively manage fraud risks in this program. For example:

· CMS’s fraud risk assessment did not fully identify inherent fraud risks. CMS did not fully identify inherent fraud risks in APTC in its 2018 assessment. Leading practices state that the first step in conducting an effective fraud risk assessment is identifying the inherent fraud risks affecting the program. This step is critical because it serves as the basis for the entire fraud risk assessment process. CMS identified 27 fraud risks, including risks related to inappropriate enrollment of dependents and misuse of various special enrollment periods.

However, we found CMS’s assessment did not include other significant risks. For example, CMS’s 2018 fraud risk assessment did not specifically identify risks related to state-based marketplaces, where states are responsible for making eligibility and enrollment decisions. According to CMS, state-based marketplaces accounted for nearly 25 percent of estimated APTC enrollees in 2018.[52] We have previously found that state-based marketplaces exercise flexibilities in eligibility-verification processes, as allowed by PPACA and CMS regulations.[53] Such a structure and flexibilities present different fraud risks than those in the federal Marketplace that, to be consistent with leading practices, are to be assessed for their likelihood and impact on APTC.

· CMS’s fraud risk assessment did not fully consider the suitability of existing controls. CMS did not fully consider the suitability of existing antifraud controls in APTC as part of its 2018 fraud risk assessment, as called for by the Fraud Risk Framework. Specifically, we found that CMS’s risk ratings did not always align with available information and may overstate the effect of existing controls.

For example, CMS’s 2018 assessment included a fraud risk related to the use of fraudulent documentation to resolve data matching issues. The assessment rated the likelihood of this risk as low, which CMS defined as “not identified or identified but very rare…no reports of risk occurring.” However, CMS’s assessment also noted that prior GAO work demonstrated that this risk had occurred and can be exploited. In this regard, in 2016, we found that several of the fictitious applicants we used in covert testing of enrollment controls obtained subsidized health coverage—in many cases using fictitious documents—in plan years 2014, 2015, and 2016.[54]

CMS Did Not Develop a Formal Antifraud Strategy to Address APTC Fraud Risks

CMS did not develop a formal antifraud strategy for APTC based on the fraud risk assessment it conducted in 2018. According to the Fraud Risk Framework, a leading practice is to develop an antifraud strategy that describes the program’s approach for addressing the prioritized fraud risks identified during the fraud risk assessment. CMS documented its 2018 fraud risk assessment in a fraud risk profile.[55] This 2018 fraud risk profile contains some elements that would help inform an antifraud strategy. For example, it identifies fraud risks and related antifraud controls.

However, the information in the profile itself does not constitute an antifraud strategy as outlined in the Fraud Risk Framework. Specifically, key elements of an antifraud strategy also include demonstrating links between fraud risk management activities and the highest internal and external residual fraud risks outlined in the fraud risk profile. CMS officials informed us that they will develop an antifraud strategy for APTC once the agency updates its fraud risk assessment for the program.

In summary, preliminary results of our covert testing and data analytics—both of which are ongoing, making the information presented in this statement subject to change—indicate that the fraud risks we previously identified in the federal Marketplace persisted in plan years 2023 through 2025. Furthermore, we identified weaknesses in CMS’s fraud risk management activities that appear to hinder the agency’s ability to effectively and proactively manage current and future fraud risks in APTC. We are continuing our work on these issues and will report our final results and make recommendations in forthcoming products, as appropriate.

Chairmen Fitzgerald and Van Drew, Ranking Members Nadler and Crockett, and Members of the Subcommittees, this completes my prepared statement. I look forward to the Subcommittees’ questions.

GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this statement, please contact Seto J. Bagdoyan, Director, Forensic Audits and Investigative Service at BagdoyanS@gao.gov or John E. Dicken, Director, Health Care at DickenJ@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement. GAO staff who made key contributions to this statement are Dave Bruno (Assistant Director), James Healy (Analyst in Charge), Erin Barry, Joshua Hatter, Barbara Lewis, Katie Mack, James Murphy, and Rachel Steiner-Dillon. Other contributors include Gerardine Brennan, Sylvia Diaz Jones, Mark MacPherson, Priyanka Panjwani, and Joseph Rini.

Appendix I: Status of GAO’s Prior Recommendations Related to Fraud Risk Management in the Federal Marketplace

Table 5: Status of GAO’s Prior Recommendations Related to Fraud Risk Management in the Federal Marketplace

|

Report |

Recommendation Language |

Status |

Status Narrative |

|

The Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) should direct the Acting Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to conduct a comprehensive feasibility study on actions that CMS can take to monitor and analyze, both quantitatively and qualitatively, the extent to which data hub queries provide requested or relevant applicant verification information. |

Closed - Implemented |

In May 2019, HHS provided GAO with a study containing statistical analyses of the data-matching performance of the data services Hub used in the application process for health care coverage established under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA). This study also included qualitative discussion of the results of the analyses, and actions implemented to improve the data-matching process. |

|

|

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should direct the Acting Administrator of CMS to track the value of advance premium tax credit and cost-sharing reduction (CSR) subsidies that are terminated or adjusted for failure to resolve application inconsistencies and use this information to inform assessments of program risk and performance. |

Closed – Not Implemented |

Tracking CSR subsidies is no longer a relevant recommendation. The Attorney General of the United States provided HHS and the Department of the Treasury with a legal opinion regarding CSR payments made to issuers of Qualified Health Plans. With that opinion, and the absence of any other appropriation that could be used to fund CSR payments, CSR payments to issuers were stopped as of October 2017. In addition, CMS cannot track the advance premium tax credit (APTC) provided to consumers during the inconsistency period unless it is granted access to IRS tax reconciliation data. |

|

|

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should direct the Acting Administrator of CMS to, in the case of CSR subsidies that are terminated or adjusted for failure to resolve application inconsistencies, consider and document whether it would be feasible to create a mechanism to recapture those costs, including whether additional statutory authority would be required to do so. |

Closed – Not Implemented |

Tracking CSR subsidies is no longer a relevant recommendation due to programmatic changes. The Attorney General of the United States provided HHS and the Department of the Treasury with a legal opinion regarding CSR payments made to issuers of Qualified Health Plans. With that opinion, and the absence of any other appropriation that could be used to fund CSR payments, CSR payments to issuers were stopped as of October 2017. |

|

|

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should direct the Acting Administrator of CMS to identify and implement procedures to resolve Social Security number (SSN) inconsistencies where the Marketplace is unable to verify Social Security numbers or applicants do not provide them. |

Closed – Implemented |

In January 2019, CMS finalized the implementation of functionality to validate and save an SSN to a consumer’s application when either an SSN inconsistency was generated as part of the original eligibility determination or an SSN was not entered at the time of application. CMS updated the application user interface to require applicants to input either an SSN or to check a box affirming (under penalty of perjury) that they do not have an SSN in order to proceed through the application without providing it. CMS also implemented a process to obtain a consumer’s SSN from acceptable consumer-provided documents. These new functionalities substantially address the recommendation that the agency identify and implement procedures to resolve SSN inconsistencies where the Marketplace is unable to verify SSNs or applicants do not provide them. |

|

|

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should direct the Acting Administrator of CMS to reevaluate CMS’s use of Prisoner Update Processing System (PUPS) incarceration data and make a determination to either: (a) Use the PUPS data as an indicator of further research required in individual cases, and to develop an effective process to clear incarceration inconsistencies or terminate coverage or (b) if no suitable process can be identified to verify incarceration status, accept applicant attestation on status in all cases, unless the attestation is not reasonably compatible with information that may indicate incarceration, and forego the inconsistency process. |

Closed – Implemented |

CMS determined that it is not practical to use the information from the Social Security Administration’s PUPS as an indicator of further research to clear incarceration inconsistencies or terminate coverage. When actively processing incarceration inconsistencies based on the information, CMS found there to be a high degree of false positives. Additionally, it does not have a readily available source through which to conduct follow-up investigations. CMS is currently accepting attestation in alignment with the recommendation. |

|

|

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should direct the Acting Administrator of CMS to create a written plan and schedule for providing Marketplace call center representatives with access to information on the current status of eligibility documents submitted to CMS’s documents processing contractor. |

Closed – Implemented |

In 2018 CMS completed integration of the Document Storage and Retrieval System (DSRS) into the Call Center’s Desktop system. DSRS provides access to consumer submitted documents. This functionality allows Call Center Representatives to see the type of supporting document that a consumer submitted to the Eligibility Support Worker. By providing this, CMS makes the application process more efficient, strengthens its eligibility determination process, and helps to make sure determinations are completed in a timely manner. |

|

|

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should direct the Acting Administrator of CMS to conduct a fraud risk assessment, consistent with best practices provided in GAO’s framework for managing fraud risks in federal programs, of the potential for fraud in the process of applying for qualified health plans through the federal Marketplace. |

Closed – Implemented |

In December 2018, CMS officials told GAO they had completed the fraud risk assessment of the Marketplace application process, based on GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework. GAO reviewed documentation submitted by the agency and concurred. By conducting a fraud risk assessment, CMS is better equipped to know whether existing control activities are suitably designed and implemented to reduce inherent fraud risk to an acceptable level. The action also helps to lower the risk of improperly providing benefits and to reduce reputational risks to the program that could arise through perceptions that program integrity is not a priority. |

|

|

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should direct the Acting Administrator of CMS to fully document prior to implementation, and have readily available for inspection thereafter, any significant decision on qualified health plan enrollment and eligibility matters, with such documentation to include details such as policy objectives, supporting analysis, scope, and expected costs and effects. |

Closed – Implemented |

CMS prepares an annual Marketplace and Related Programs Cycle Memo to fulfill reporting requirements for internal control. The memo describes all significant eligibility and enrollment policy and process changes, including new internal key controls associated with these changes. In addition, each year CMS publishes its Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters (i.e., ‘Payment Notice’) in draft and then in final. This regulation provides a comprehensive description of major proposed Marketplace changes that allows CMS to document prior to implementation and in a public forum, any significant decisions on qualified health plan enrollment and eligibility matters. |

|

|

As part of its efforts to assess and document the feasibility of approaches to identify the deaths of enrollees that may occur during the plan year, the Administrator of CMS should specifically assess and document the feasibility of approaches—including rechecking the full death file—to identify the deaths of individuals prior to automatic reenrollment for subsequent plan years and, if appropriate, design and implement these verification processes. |

Closed – Implemented |

In December 2018, CMS provided GAO with its assessment of the feasibility of identifying deceased individuals prior to automatic reenrollment into the federally facilitated marketplace. Specifically, CMS determined that it would be feasible to perform a periodic death match. CMS stated that it is outlining plans and expects to complete the process within three years. GAO found that the federally facilitated marketplace checks applicant information against SSA’s full death file before enrolling and not after. However, by performing a periodic death match, CMS will meet the intent of GAO’s recommendation to prevent automatic reenrollment of deceased individuals. |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑26‑108811

Related GAO Products

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Preliminary Results from Ongoing Review Suggest Fraud Risks in the Advance Premium Tax Credit Persist. GAO‑26‑108742. Washington, D.C.: December 3, 2025.

Health Insurance: Enhanced Data Matching Could Help Prevent Duplicate Benefits and Yield Substantial Savings. GAO‑25‑106976. Washington, D.C.: September 25, 2025.

Payment Integrity: Additional Coordination Is Needed for Assessing Risks in the Improper Payment Estimation Process for Advance Premium Tax Credits. GAO‑23‑105577. Washington, D.C.: March 9, 2023.

Federal Health-Insurance Marketplace: Analysis of Plan Year 2015 Application, Enrollment, and Eligibility-Verification Process. GAO‑18‑169. Washington, D.C.: December 21, 2017.

Improper Payments: Improvements Needed in CMS and IRS Controls over Health Insurance Premium Tax Credit. GAO‑17‑467. Washington, D.C.: July 13, 2017.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Results of Enrollment Testing for the 2016 Special Enrollment Period. GAO‑17‑78. Washington, D.C.: November 17, 2016.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Results of Undercover Enrollment Testing for the Federal Marketplace and a Selected State Marketplace for the 2016 Coverage Year. GAO‑16‑784. Washington, D.C.: September 12, 2016.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Final Results of Undercover Testing of the Federal Marketplace and Selected State Marketplaces for Coverage Year 2015. GAO‑16‑792. Washington, D.C.: September 9, 2016.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: CMS Should Act to Strengthen Enrollment Controls and Manage Fraud Risk. GAO‑16‑29. Washington, D.C.: February 23, 2016.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Preliminary Results of Undercover Testing of the Federal Marketplace and Selected State Marketplaces for Coverage Year 2015. GAO‑16‑159T. Washington, D.C.: October 23, 2015.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Observations on 18 Undercover Tests of Enrollment Controls for Health-Care Coverage and Consumer Subsidies Provided under the Act. GAO‑15‑702T. Washington, D.C.: July 16, 2015.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Preliminary Results of Undercover Testing of Enrollment Controls for Health Care Coverage and Consumer Subsidies Provided Under the Act. GAO‑14‑705T. Washington, D.C.: July 23, 2014.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]GAO, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Preliminary Results of Ongoing Review Suggest Fraud Risks in the Advance Premium Tax Credit Persist, GAO‑26‑108742 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 3, 2025).

[2]26 U.S.C. § 36B and 42 U.S.C. § 18082.

[3]Plan year generally aligns with calendar year.

[4]See, for example, GAO, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Results of Undercover Enrollment Testing for the Federal Marketplace and a Selected State Marketplace for the 2016 Coverage Year, GAO‑16‑784 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 12, 2016); Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Final Results of Undercover Testing of the Federal Marketplace and Selected State Marketplaces for Coverage Year 2015, GAO‑16‑792 (Washington, D.C.: Sept 9, 2016); and Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: CMS Should Act to Strengthen Enrollment Controls and Manage Fraud Risk, GAO‑16‑29 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 23, 2016). Appendix I provides the status of GAO’s prior recommendations related to fraud risk management in the federal Marketplace. A list of related GAO products is included at the end of this statement.

[6]GAO, Improper Payments: Improvements Needed in CMS and IRS Controls over Health Insurance Premium Tax Credit, GAO‑17‑467 (Washington, D.C.: July 13, 2017).

[8]As discussed later in this statement, eligibility for APTC generally requires household income of at least 100 percent or more of the federal poverty level.

[9]SSA does not guarantee the accuracy of the information in the full death file. SSA has historically collected death information about SSN-holders, so it does not pay Social Security benefits to deceased individuals and to establish benefits for survivors. SSA receives death reports from a variety of sources, including states, family members, funeral directors, post offices, financial institutions, and other federal agencies. We refer to SSA’s complete file of death records as “the full death file.” A subset of the full death file that may not include death data received by the states, which SSA calls “the Death Master File,” is available to the public.

[10]GAO, A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, GAO‑15‑593SP (Washington, D.C.: July 2015).

[11]Alternatively, individuals can choose to get all the benefit of the credit when they file their tax return for the year. See 26 U.S.C. § 36B(f) and 45 C.F.R. § 155.310(d)(2)(i).

[12]The cost of a benchmark plan varies based on factors including age and location. Although premium tax credits, including APTC, are calculated based on the premium of a benchmark plan, consumers do not need to be enrolled in a benchmark plan to use these tax credits.

[13]American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Pub. L. No. 117-2, § 9661, 135 Stat. 4, 182.

[14]An Act To provide for reconciliation pursuant to title II of S. Con. Res. 14, Pub. L. No. 117-169, § 12001, 136 Stat. 1818, 1905 (2022).

[15]According to HealthCare.gov, agents may work for a single health insurance company, whereas brokers may represent several companies.

[16]To sell plans in the federal Marketplace, agents and brokers must also verify their identity, complete required training, and have signed agreements in place with CMS.

[17]45 C.F.R. § 155.220(j)(2).

[18]Pub. L. No. 114-86, 130 Stat. 546 (2016).

[19]Pub. L. No. 116-17, § 2(a), Stat. 113, 131 – 132 (2020), codified at 31 U.S.C. § 3357. The act requires these guidelines to remain in effect, subject to modification by OMB as necessary and in consultation with GAO.

[20]Office of Management and Budget, Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control, OMB Circular No. A-123 (Washington, D.C.: July 15, 2016).

[21]Office of Management and Budget, Establishing Financial and Administrative Controls to Identify and Assess Fraud Risk, CA-23-03 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 17, 2022).

[22]To demonstrate eligibility for a low-income special enrollment period, consumers were allowed to self-attest that their income was less than 150 percent of the federal poverty level. Documentation of eligibility for this special enrollment period was not required prior to enrolling. According to agency officials, this special enrollment period is no longer available as of August 25, 2025.

[23]In one case, we called an insurance broker from a list on HealthCare.gov. In the other case, we were connected to an insurance broker after clicking on a potentially misleading advertisement offering a monthly cash subsidy (rather than subsidized insurance coverage). The broker said that he was not familiar with the online advertisement and explained that the money would pay for health insurance premiums rather than a cash subsidy.

[24]According to agency officials, CMS is taking steps to address weaknesses in enrollment controls. For example, CMS issued a rule in June 2025 intended to strengthen controls related to income verification and use of special enrollment periods, among other things. However, as of December 2025, a federal district court has issued an order partially suspending the effective date of the rule pending a final decision in ongoing litigation.

[25]See GAO‑16‑784, GAO‑16‑792, and GAO‑16‑29.

[26]We expected our fictitious applicants to fail initial identity proofing because the system used by HealthCare.gov asks the consumer questions based on their credit report. Our fictitious applicants do not have credit reports from which the system can derive questions.

[27]CMS guidelines offer flexibility in how EDE entities may complete identity proofing for a consumer.

[28]CMS also began requiring verifiable SSNs on applications submitted by agents and brokers through direct enrollment pathways.

[29]In one instance, we submitted fictitious documentation to support citizenship for an applicant’s 2025 application. The Marketplace verified the applicant’s citizenship and applied the results to both the 2024 and 2025 enrollments.

[30]This includes applications for the four fictitious applicants we initially enrolled in plan year 2024.

[31]See GAO‑16‑784, GAO‑16‑792, and GAO‑16‑29.

[32]Public Law No. 119-21—commonly known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act—repealed these statutory repayment limits, applicable to tax years beginning after December 31, 2025. An Act To provide for reconciliation pursuant to title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Pub. L. No. 119-21, title VII, § 71305, 139 Stat. 72, 324 (2025).

[33]Certain noncitizens may be eligible for marketplace coverage without an SSN. These individuals may file taxes and reconcile APTC with an individual taxpayer identification number (ITIN).

[34]Tax year 2023 was the most recent available data when we began our work July 2024.

[35]For our analysis, we determined that APTC had no evidence of reconciliation if none of the SSNs associated with the federal Marketplace application matched an SSN in the reconciliation tax data. We limited our analysis to federal Marketplace enrollees that provided SSNs because CMS enrollment data do not contain ITINs for consumers who do not have SSNs. Further, we did not examine the accuracy of the tax filings for consumers who did reconcile APTC.

[36]For example, APTC paid on behalf of fictitious enrollees will not be reconciled as these enrollees will not file federal income taxes.

[37]An individual under 65 with income below $14,600 or a married couple under 65 filing jointly with income below $29,200 generally are not required to file a tax return. However, an APTC recipient is required to file a tax return even if the individual is not otherwise required to do so.

[38]We obtained plan year 2023 enrollment data from CMS in October 2024 and plan year 2024 enrollment data in May 2025.

[39]Traditional identity theft uses a real person’s identity to commit fraud. Synthetic identity fraud involves creating a fictional identity by combining real and fake personal information. See GAO, Social Security Administration: Actions Needed to Help Ensure Success of Electronic Verification Service, GAO‑24‑106770 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2024).

[40]We limited our analysis of death data matches for this statement to plan year 2023 because it was the most recent, complete plan year as of November 2024, when we obtained death data from the Social Security Administration. We are analyzing death data matches for plan year 2024 enrollments as part of our ongoing work.

[41]For purposes of this statement, we refer to the end of the month of death listed in the full death file as the reported date of death. It is not possible to determine from data matching alone whether these matches definitively identify individuals receiving coverage with an associated subsidy who were deceased because individuals can be erroneously listed in the full death file.