CONSUMER PROTECTION

Expeditious Actions Needed to Implement a Government-wide Strategy and Related Efforts to Counter Scams

Statement of Seto J.

Bagdoyan, Director,

Forensic Audits and Investigative Service

Before the Special Committee on Aging, U.S. Senate

For Release on Delivery Expected at 3:30 p.m. ET

GAO-26-108842

A testimony before the Special Committee on Aging, U.S. Senate

For more information, contact: Seto J. Bagdoyan at BagdoyanS@gao.gov

What

GAO Found

What

GAO Found

Scams occur in a variety of forms and are a growing risk to consumers.

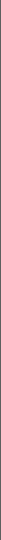

Examples of a Scam Execution Process

Note: Other types of contact methods, scams, and payment methods exist.

At least 13 federal agencies engage in a range of activities related to countering scams. The agency activities cover a spectrum of roles intended to prevent, detect, and respond to scams. However, each agency largely carries out these activities independently. None of the 13 federal agencies that GAO spoke with were aware of a government-wide strategy to guide efforts to combat scams, nor did GAO independently identify such a strategy. In its April 2025 report, GAO recommended that the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) lead a federal effort, in collaboration with other agencies, to develop and implement a government-wide strategy to counter scams and coordinate related activities. The FBI recently outlined actions to address this recommendation.

The Consumer Protection Financial Bureau (CFPB), the FBI, and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) collect and report on consumer complaints both directly and from other agencies. Data limitations prevent agencies from determining a total number of scam complaints and financial losses. Accordingly, there is no single, government-wide estimate of the total number of scams and financial losses. Similarly, federal agencies have not produced a common, government-wide definition of scams. A government-wide estimate would capture the scale of scams, and a common definition is necessary for producing such an estimate and for developing a government-wide strategy.

In its April 2025 report, GAO made separate recommendations to CFPB, the FBI, and FTC to (1) develop a common definition of scams, (2) harmonize data collection, (3) report an estimate of the number of scam complaints each receives and (4) produce a single, government-wide estimate of the number of consumers affected by scams. In a recent update, the FBI and FTC outlined various concerns with these recommendations, such as differing authorities and mandates among agencies. However, GAO maintains that these recommendations remain valid. In October 2025, CFPB stated that it will monitor FBI and FTC actions before determining if any actions of its own are warranted.

Why GAO Did This Study

Scams, a method of committing fraud, involve the use of deception or manipulation intended to achieve financial gain. Scams often cause individual victims to lose large sums—in some cases their entire life savings. Federal agencies such as the FBI and FTC have responsibilities that include preventing and responding to scams against Americans.

This statement discusses (1) federal agencies’ activities to prevent and respond to scams and the need for a comprehensive, government-wide strategy to guide their efforts and (2) federal agencies’ activities to compile scam-related consumer-complaint data and estimate the total number of scams and related financial losses. It also provides updates on the status of 3 agencies’ actions to address applicable recommendations.

This statement is based on GAO’s April 2025 report on federal efforts to combat scams (GAO-25-107088). For that report, GAO analyzed publicly available information (including prior GAO reports) and relevant agency documents. GAO also interviewed officials from 13 different federal agencies involved in countering scams.

What GAO Recommends

In April 2025 GAO made 16 total recommendations to CFPB, the FBI, and FTC. The FBI disagreed with three recommendations, including those related to the development of a government-wide estimate and a definition of scams. FTC neither agreed nor disagreed with the five recommendations made to it. CFPB did not respond with comments. The agencies’ responses to certain recommendations are discussed in this statement.

Chairman Scott, Ranking Member Gillibrand, and Members of the Committee:

I am pleased to appear before you today to discuss findings from our April 2025 report on scams that target consumers, including older adults, and the various ways federal agencies counter such scams.[1] Scams, a method of committing fraud, involve the use of deception or manipulation intended to achieve financial gain for the scammer. In perpetrating various scams, scammers deceive victims into making a payment or providing information to make a payment to benefit the scammer. These payments are often made via Peer-2-Peer (P2P) payment applications, gift cards, and wire transfers.[2] In addition to inflicting emotional distress, scams have caused individual victims to lose tens of thousands of dollars, and, in some cases, their entire life savings.

Criminal organizations operating throughout the country and world use thousands of scammers to target victims and induce them into giving them their money under false pretenses. According to the United Nations, these organized crime groups continue to expand their operations and increase the sophistication of scams.[3]

A single example highlights the scope and reach of scams. A 2023 international police operation against online financial crime, including scams, concluded with over 3,000 arrests and the seizure of $300 million worth of assets across 34 countries, including the United States.[4] Within the United States, the Department of Justice (DOJ) has also identified the involvement of transnational criminal organizations that have taken tens of millions of dollars from Americans through scams.

My remarks today summarize findings from our April 2025 report that are of particular interest to the Committee for purposes of this hearing. Specifically, I will describe our findings related to:

1. federal agencies’ activities to prevent and respond to scams and the need for a comprehensive, government-wide strategy to guide their efforts, as well as the status of agencies’ actions to address our applicable recommendations.

2. federal agencies’ activities to compile scam-related consumer-complaint data and estimate the total number of scams and related financial losses, as well as the status of agencies’ actions to address our applicable recommendations.

Detailed information on the objectives, scope, and methodology for this work can be found in our April 2025 report.[5] In addition, for this statement we summarize information recently provided by federal agencies in October and November 2025 on the status of actions they have taken or planned in response to our April 2025 recommendations.

We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe the evidence we obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Several federal agencies play a role in preventing and responding to scams including:

· Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB),

· the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Executive Office for United States Attorneys (within the DOJ),

· the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and

· the Department of the Treasury.[6]

Scams involving the use of information technology have been around for decades. In an early common scheme, text messages were sent to individuals requesting that funds be sent to someone purporting to be a family member.

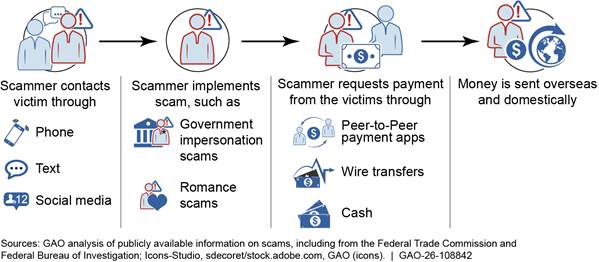

According to our analysis of publicly available information, scams today can occur in different forms. Scams involve a scammer contacting the victim, through means such as text message or social media; engaging the victim with a particular scam scheme; and requesting a payment, such as a wire transfer, for a false purpose. Figure 1 illustrates how scams may generally be carried out.

Figure 1: Common Examples of the Scam Execution Process

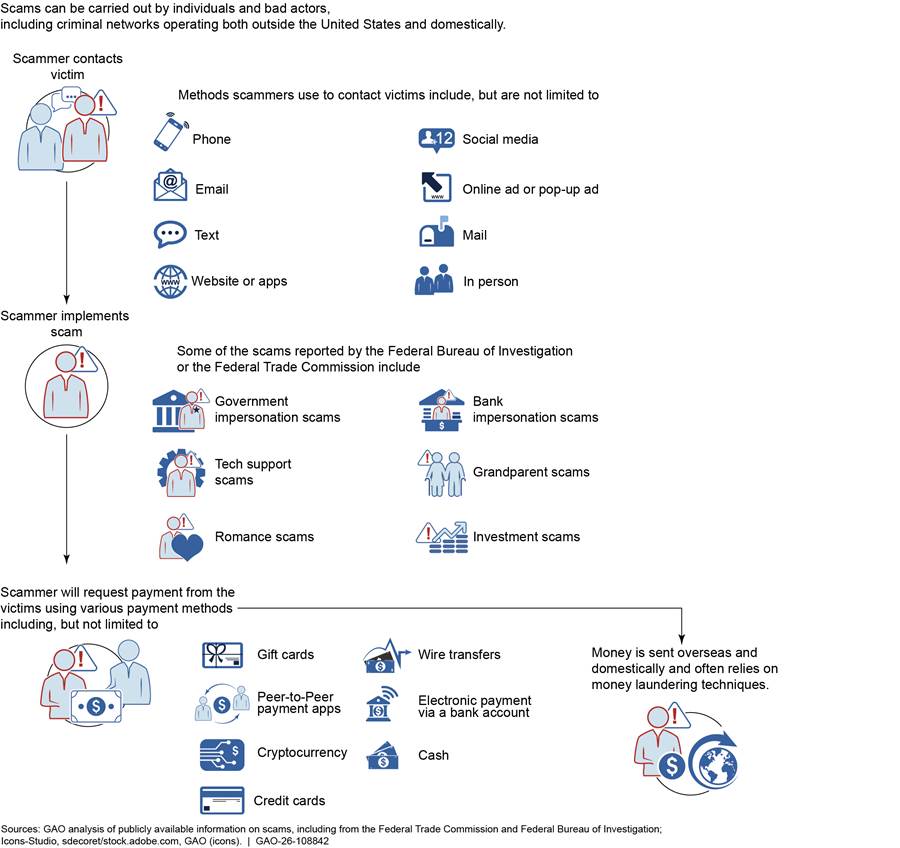

Scammers are constantly finding new ways to scam victims. CFPB, the FBI, and FTC have identified numerous types of scams. Figure 2 provides a nonexhaustive listing of scam types.

Figure 2: Examples of Scam Types

Below are characteristics of some of the most frequently used methods by scammers to obtain funds from victims, as cited in FTC reports.

· P2P payment applications allow consumers to quickly send and receive money. Depending on the payment provider, a P2P payment can be initiated from a consumer’s online bank account portal or a mobile application. According to the FTC, scammers may trick the victim into sending them money through a P2P payment application, because once the individual sends the money, it is difficult to get it back.

· Gift cards hold specific cash value that can be used for purchases. Scammers can request that individuals purchase a gift card and ask for the gift card number and PIN. Scammers deceive their victims by telling them, for example, that the gift card number is to pay the government for taxes or fines, pay for tech support, or for some other fictitious reason. The gift card number and PIN allow the scammers to access the funds that their victim has loaded into the card.

· A wire transfer is the transfer of funds from one person to another. The transfer can be domestic or international. Wire transfers can be initiated through a financial institution or a money services business.

Scams can be carried out by individuals and criminal networks operating both outside the United States and domestically. Multiple domestic law enforcement investigations have identified criminals operating from international call centers working to defraud Americans. For example, scammers in foreign-based call centers have called Americans and falsely identified themselves as federal law enforcement officers or other government officials to request that victims send money to avoid arrest or other economic consequences. The funds that criminals obtain from these scams may be linked to other illicit activities, such as human trafficking.

A 2024 DOJ study found persons aged 60 or older and persons aged 59 or younger experienced fraud at the same rate.[7] However, older adults are more likely to experience greater losses and are less likely to report scams. Agencies such as CFPB, the FBI, and FTC and Congress have initiatives designed specifically to help older adults avoid scams. Additional resources or specialized personnel are sometimes employed by agencies or businesses to respond to older victims, but the resolution process remains the same as for other victims.

Multiple Federal Agencies Engage in Activities to Counter Scams, but No Government-wide Strategy Currently Guides Their Efforts

Officials from the 13 federal agencies we spoke with for our April 2025 report stated that they were engaged in a range of activities related to countering scams. The agency activities cover a spectrum of roles intended to prevent, detect, and respond to scams. Each agency stated it engaged in some form of preventative activities, such as consumer education or outreach (e.g., publishing consumer alerts and articles related to fraud and scams). About half of the agencies reported engaging in information-gathering activities, such as recording or reporting on scams. Most of the agencies also reported taking some form of action to respond to or investigate scams.

Although at least 13 federal agencies engage in activities related to countering scams perpetrated against victims, each agency has its own mandate and authority, with each largely carrying out activities related to countering scams independently. However, in some instances, agencies coordinate efforts, such as by providing consumer education or by sharing consumer complaint information. For example, FTC maintains the Consumer Sentinel Network (Sentinel). Sentinel, a collaborative effort involving 46 contributors including the FBI, is a consumer-complaint reporting database made accessible to law enforcement agencies. FTC officials told us they analyze Sentinel data for consumer complaint trends and publish scam-related consumer alerts and articles on FTC’s website. Some of these efforts are implemented through official bodies, such as the FTC, intended to address crimes against older adults.[8]

Officials from the 13 federal agencies we interviewed noted that they were not aware of a government-wide, or national, strategy to guide government efforts to combat scams.[9] Our research into this topic did not identify an existing strategy that could be used government-wide to counter scams.

For our April 2025 report, FTC and Treasury shared their views with us on a single, comprehensive, government-wide strategy to counter scams. CPFB and the FBI did not offer specific views on such a strategy. According to FTC officials, no single agency has the jurisdiction and authorities to tackle the diversity of fraud and scams in the marketplace government-wide. They stated that a government-wide strategy could help overcome those jurisdictional barriers, if significant resources could be applied to tackle multifaceted and evolving scams. FTC added that any comprehensive, government-wide strategy must include a focus on criminal and civil law enforcement.

Treasury officials noted that many federal law enforcement and other agencies have overlapping mandates when it comes to fraud and scams, and a fully coordinated law enforcement strategy may in practice be difficult to coordinate and implement among agencies. Further, Treasury officials noted that to have a government-wide strategy and use it to coordinate efforts to counter scams would involve several key agencies, such as CFPB, the FBI, FTC, and Treasury.

Some industry representatives and consumer organizations have advocated for a government-wide strategy to counter scams. For example, in its November 2023 meeting, the Federal Advisory Council to the Federal Reserve Board stated in its minutes that a government-wide approach is needed to counter fraud and scams.[10] Likewise the American Bankers Association stated in a May 2024 testimony before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations that a national antiscam strategy needs to be developed.[11] According to the association, “Focusing on only one aspect or one step in the [scam] process will not stop this surge of scams. Rather, a holistic approach to address all the entities and elements of a scam has the best chance of being successful.”

Other countries, such as Australia, have developed and implemented government-wide strategies and identified specific entities to counter scams, with attributable reductions in the level of scams. In this regard, Australia created a National Anti-Scam Centre within its Competition and Consumer Commission that draws on expertise across government, law enforcement, industry, and consumer groups to make Australia a harder target for scammers.[12] Together, the entities collect and share scam data and intelligence, implement scam prevention and disruption initiatives, and provide better awareness alerts and education resources to help consumers identify and avoid scams. The Australian government has reported that the National Anti-Scam Centre’s efforts have led to a 13.1 percent decline in reported scam losses from 2022 to 2023.

Our prior work has shown that in some instances, it may be appropriate or beneficial for multiple agencies to be involved in the same programmatic or policy area due to the complex nature of the issue or magnitude of the federal effort.[13] However, having multiple agencies involved in the same programmatic area could create the risk of fragmentation of effort or overlap of multiple activities—especially absent a strategy to coordinate and manage such activities—potentially limiting their effectiveness and impact.[14]

In our April 2025 report, we recommended that the Director of the FBI lead a U.S. government effort to develop and implement a government-wide strategy to counter scams and coordinate related activities. This effort should be done in collaboration with the Director of CFPB, the Chair of FTC, the Secretary of the Treasury, and other agencies, as appropriate. As discussed below, this effort should address issues such as a common definition for scams and consumer complaint reporting. As appropriate, and consistent with desired characteristics we have identified in our prior work, a strategy should also define agency roles, responsibilities, and authorities; identify necessary resources; and identify any legislative, regulatory, or administrative changes needed to enable a comprehensive, coordinated response.

In comments to our April 2025 report, the FBI concurred with our recommendation and noted that it is fully committed to this mission and leading this effort. In October 2025, the FBI provided us with an update, stating that the development and implementation of a government-wide strategy will involve:

· A multi-agency working group. The FBI described the need to establish a multi-agency working group to develop an international center of excellence for the United States to mitigate the cyber-enabled fraud threat. According to the FBI, this center will allow governmental entities to share information, deconflict, and unite stakeholders, including law enforcement partners, regulatory agencies, among others.

· Legislative updates and regulatory reform. The FBI stated that legislative updates are needed to close legal gaps, strengthen enforcement capabilities, and ensure agencies have the necessary authorities to combat cyber-enabled fraud. In addition, regulatory reform may be needed given that cyber-enabled fraud and transnational scams continue to evolve which exposes gaps in reporting. In October 2025, the FBI informed us that it plans to work with the Departments of Justice and the Treasury to explore areas of regulatory reform.

· Collaboration with private sector organizations and others. According to the FBI, improvements to fraud detection and prevention will be explored with financial institutions, tech companies, and other private sector organizations, as well as consumer advocacy organizations.

· Additional funding. The FBI explained that additional funding will be needed to successfully implement a government-wide strategy. This includes dedicated funding, expanded staffing, and centralized expertise, as well as acquiring advanced tools, expanding cryptocurrency tracing capabilities, and leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning to analyze datasets to identify points of attribution.

We will continue to monitor the FBI’s actions to develop and implement a government-wide strategy to counter scams.

Federal Agencies Compile Scam-Related Complaint Data, but Limitations Exist in Estimating the Extent of Scams and Related Losses

Of the eight federal agencies that receive scam-related consumer complaints, three agencies (CFPB, the FBI, and FTC) publish annual reports summarizing consumer complaint data.[15] However, the data informing these reports have limitations. For example, within the FBI, the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) receives consumer complaints related to internet crime, including identity theft, data breaches, and scams.[16] The way the FBI complaint data are collected, however, limits their utility in reporting an aggregate count of the total number of complaints specifically related to scams. One such limitation is that the IC3 does not use predefined fields that would allow consumers to indicate when a complaint is related to a scam.[17]

CFPB, the FBI, and FTC each can calculate an estimate of complaints they receive related to scams but not the exact number of scam complaints. For example, FBI officials noted that FBI annual reports do not include a line item for total scam complaints received and associated dollar losses. For our April 2025 report, the FBI compiled the total at our request. According to FBI officials, in 2023, IC3 estimated that it received over 589,355 complaints related to scams, with losses of $10.55 billion. Similarly, CFPB estimated that in 2023, it received 3,210 complaints potentially regarding scams over P2P platforms. CFPB officials stated that they did not have a loss estimate for scam-related complaints because they do not require consumers to include dollar losses when filing a complaint.

The underreporting of scams also complicates calculating a government-wide estimate of scams. According to DOJ and FTC, most consumer fraud goes unreported. For example, in 2015, DOJ estimated that 15 percent of the nation’s fraud victims report their crimes to law enforcement.[18] Consequently, the numbers of instances of scams and financial-loss amounts are likely understated. Similarly, a study cited by FTC reported that about 5 percent of people who experienced mass-market consumer fraud complained to a Better Business Bureau or a government agency.[19] According to FTC officials, the agency has estimated the amount of consumer fraud losses—not specific to just scams—taking into account underreporting, but officials stated more research was needed to accurately extrapolate a single estimate of scams based on consumer complaint data.[20]

Additionally, according to the Federal Reserve, accurate quantification of scams is often challenging because of multiple operational scam definitions and a lack of consistency in approaches for classifying different types of scams. In spring 2023, the Federal Reserve established a scams definition and classification work group. This work group consisted of payments and fraud experts from different disciplines, including federal agencies and financial institutions. The goal of the work group was to provide a more consistent foundation for scams reporting to better understand and mitigate the problem. Federal Reserve officials told us that it was important to have a consistent scam definition to help ensure that different agencies are counting the same thing, when quantifying scams.[21]

A desirable characteristic of national strategies includes defining the issue or problem that a particular strategy is intended to address. We have previously reported that the use of common definitions promotes, among other things, more effective intergovernmental operations and helps avoid duplication of effort.[22] In this regard, the definition by the Federal Reserve offers a baseline around which federal agencies and others could collaborate and arrive at a common understanding of what constitutes a scam. Alternatively, agencies could work together to develop a different agreed-upon definition.

As we explained in our April 2025 report, developing a government-wide definition of scams and improving consumer scam complaint reporting could assist agency efforts to compare data across agencies, develop an overall estimate of the total number of scams, and assess trends. Most importantly, agency efforts to improve data collection and reporting about the types and extent of scams would help government agencies, Congress, and industry target their preventative efforts and measure progress in scam prevention and would inform an effective antiscam strategy. Because scammer tactics are continuously evolving with technology, having comprehensive data on scams would help agencies better understand new scams and develop ways to counter them.

Specifically, in our April 2025 report, we made 16 separate recommendations to the Director of CFPB, the Director of the FBI, and the Chair of FTC. Among these recommendations, we made the following four recommendations to each of the three agencies related to improving, in collaboration with each other, how they collect and report data on scams: (1) explore ways to harmonize data collection to better identify scams, (2) use the agency’s data collection and analysis to produce and report an estimate of the number of complaints it receives and the associated financial losses resulting from scams, (3) collaborate, develop, and report on a single, government-wide estimate of the number of consumers affected by, and a dollar losses resulting from, scams, factoring in an estimate of incidents not reported and (4) develop a government-wide definition of scams. CFPB did not provide comments on our April 2025 report, while the FBI concurred with the first two recommendations listed here and did not concur with the last two. FTC neither agreed nor disagreed with the four recommendations listed here. Below are recent updates provided to us by CFPB, the FBI, and FTC on actions they have taken or plan to take in response to our recommendations.

CFPB: In an October 2025 update, CFPB did not specifically discuss actions it is taking to address the recommendations we made. However, CFPB stated that it shares our perspective that federal efforts must be as effective as possible. CFPB stated that for several reasons, such as implementation of the government-wide strategy to counter scams, it believes it is prudent to closely monitor the actions of the FBI, FTC, and other stakeholders before determining whether any further CFPB action is warranted. Further, for the recommendation to adopt the definition of scams developed by the Federal Reserve or work with the FBI, FTC, and other agencies to develop a common definition of scams and related scam types, CFPB stated that agreed-upon definitions and standards are necessary for the agency to address the GAO’s recommendations in whole or in part.

FBI: In October 2025, the FBI provided an update on its actions and plans to address our recommendations.

· For the recommendation regarding data harmonization, the FBI explained that it will work with FTC and other partners to explore opportunities for alignment, such as shared scam-type classification, which would improve coordination in defining and tracking scams. The FBI added that it supports collaborative efforts to improve data consistency where alignment is feasible and mutually beneficial.

· The FBI informed us that it will explore options to more systematically aggregate and report scam-related data, including through enhancements to existing reporting platforms.

· The FBI added that it cannot address the recommendation to collaborate with other agencies to develop and report a single, government-wide estimate of the number of consumers affected by, and dollar losses resulting from, scams, factoring in an estimate of incidents not reported, as framed. However, it supports continued coordination across agencies and will do its part to contribute meaningful data and analysis to inform the government’s collective fraud prevention efforts. Specifically, the FBI explained that it does not believe diverting law enforcement resources to develop independent estimates would be a wise or effective use of taxpayer funds since its focus remains on disrupting criminal networks, protecting the public, and preventing future scams. The FBI added that agencies, such as FTC, with statistical or consumer protection mandates are better positioned to lead such work.

Our recommendation directs agencies to collaborate on developing a single government-wide estimate of scams and scam losses. We did not recommend that the FBI develop the government-wide estimate independently. As we explained in our April 2025 report, fraud estimates, including those specifically addressing scams, can demonstrate the scope of the problem, help improve oversight prioritization, and help determine the return on investment from activities to mitigate fraud.

· For the recommendation to develop a government-wide definition of scams, the FBI stated that it supports continued interagency engagement to explore opportunities for definitional alignment where appropriate. The FBI shares FTC’s view that while interagency consultation is valuable, any collaborative effort to define “scams” must respect the distinct authorities, mandates, and enforcement responsibilities of each agency. The FBI noted that developing a singular, government-wide definition of scams, while conceptually beneficial, poses practical challenges, particularly given the diverse statutory frameworks under which federal agencies operate. The FBI added that it does not have the authority to compel other agencies to adopt a unified definition and believes that any shared framework should be the product of voluntary consensus based on each agency’s operational and legal context.

While we acknowledge the FBI’s concerns, our recommendation calls for agencies to collaborate with each other in developing a scam definition. It is important to define terms and use definitions consistently, including using common definitions when measuring the volume and impact of scams over time. As we explained in our April 2025 report, using a common definition for this type of crime would improve the ability of agencies to compare and aggregate data across agencies, assess trends, and show progress in fraud prevention.

FTC: In November 2025, FTC provided an update on its data collection and estimate on scams efforts.

· FTC stated that harmonizing the data can be difficult but noted that it is important to provide better information to law enforcement users and better analysis to the public. The FTC explained that it will continue to review its intake mapping and will also explore ways to improve the harmonization, including the data mapping for its major contributors.

· In response to the recommendation to develop an estimate of the number of consumer reports pertaining to scams, FTC stated it will review its “fraud” and “other” topic categories in its Sentinel database to determine if there should be any adjustments to those Sentinel categories. While we appreciate FTC’s effort to review its categories, this action does not address the recommendation to report an estimate of the number of complaints it receives and the associated financial losses resulting from scams. We understand that FTC already reports on fraud complaints; however, this category is broad. In our April 2025 report, we recommended FTC estimate and report the number of complaints it receives and the associated financial losses resulting from scams.

· Regarding the recommendation related to developing a government-wide estimate of scams and scam losses, FTC stated that it already makes efforts to report its fraud-related data and estimates of consumer impact, which include reports from many other government agencies, such as the FBI. According to FTC, its 2023 report to Congress, Protecting Older Consumers, estimated $158.3 billion in consumer fraud losses in 2023, with an estimated $61.5 billion lost by older adults.[23] However, this estimate is not a single, government-wide estimate of losses resulting from scams. As we stated in our April 2025 report, we understand that each agency has its own mandate and authority. We continue to believe, however, that a single, government-wide measure and a common definition of scams will best support a multiagency approach and response to scams.

· Regarding the development of a common definition of scams, FTC expressed concerns about the uniform adoption of the Federal Reserve’s definition of “scams.” FTC officials stated that they have used the terms “scam” and “fraud” interchangeably for many decades, and they have established methods for tracking consumer report data. Further, the FTC explained that the Federal Reserve’s definition of scam does not align with its statutory responsibilities related to prohibiting a wide range of conduct. FTC agreed that additional collaboration with CFPB, the FBI, and other agencies is needed to fight scams and fraud.

As the Federal Reserve has made clear, accurate quantification of scams is often challenging because of multiple operational scam definitions and a lack of consistency in approaches for classifying different types of scams. Federal Reserve officials told us that it was important to have a consistent scam definition to help ensure that different agencies are counting the same thing, when quantifying scams. Further, a common definition is necessary for the development of a government-wide strategy. Our recommendation gives FTC an option to adopt the definition of scams developed by the Federal Reserve or work with CFPB and the FBI and other affected agencies to develop a common definition of scams and related types. While we understand there may be limitations with agencies’ authority and the Federal Reserve scam definition, we continue to believe that the agencies should work together to adopt a definition of scams.

While the three agencies described actions they plan to take to implement our recommendations, they did not specify whether any of these are under way or when they might be initiated. Given the scope, scale, and nature of scams targeting consumers and the extent of financial and other harm they inflict, swift action by these agencies is needed to implement our recommendations. As discussed above, some agencies noted in our April 2025 report that they did not agree with some of our recommendations—such as establishing a common definition of scams and estimating the extent of scams. While we acknowledge the challenges involved in such undertakings, we continue to believe our recommendations are warranted and should be implemented expeditiously. Accordingly, we will continue to monitor the three agencies’ efforts to implement our recommendations.

Chairman Scott, Ranking Member Gillibrand, and Members of the Committee, this concludes my prepared statement. I look forward to your questions.

GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact Seto J. Bagdoyan, Director, Forensic Audits and Investigative Service at BagdoyanS@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement. GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony are David Bruno (Assistant Director), Samantha Sloate (Analyst in Charge), Colin Fallon, Brenda Mittelbuscher, Gloria Proa, Joseph Rini, Daniel Silva, and Rachel Steiner-Dillon.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

Dave Powner, Acting Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]GAO, Consumer Protection: Actions Needed to Improve Complaint Reporting, Consumer Education, and Federal Coordination to Counter Scams, GAO‑25‑107088 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 8, 2025). This statement refers to persons 60 and older when using the term “older adults.” This definition is consistent with the requirements in Section 2(1) of the Elder Abuse Prevention and Prosecution Act, which references Section 2011 of the Social Security Act (42 U.S.C. 1397j(5)) (defining “elder” as an individual age 60 or older).

[2]P2P payment applications allow consumers to send and receive money from mobile devices through a linked bank account. A gift card is a plastic card or other payment code or device that is purchased on a prepaid basis; issued at a specific amount; and redeemable at a single merchant or an affiliated group of merchants that share the same name, mark, or logo. A wire transfer is a way to send money electronically to a domestic or an international recipient.

[3]United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Casinos, cyber fraud, and trafficking in persons for forced Criminality in Southeast Asia (September 2023), https://www.unodc.org/roseap/uploads/documents/Publications/2023/TiP_for_FC_Policy_Report.pdf.

[4]Interpol, USD 300 million seized and 3,500 suspects arrested in international financial crime operation (Dec. 19, 2023), https://www.interpol.int/News‑and‑Events/News/2023/USD‑300‑million‑seized‑and‑3‑500‑suspects‑arrested‑in‑international‑financial‑crime‑operation.

[6]For the full list of the 13 federal agencies we identified as playing a role in preventing and responding to scams, see GAO‑25‑107088.

[7]Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, Examining Financial Fraud Against Older Adults (Mar. 20, 2024), https://www.ojp.gov/library/publications/examining-financialfraud-against-older-adults. The National Institute of Justice is the research, development and evaluation agency of the U.S. Department of Justice.

[8]In 2022, Congress enacted the Stop Senior Scams Act, requiring the establishment of an older-adult scam prevention advisory group. In 2022, FTC established the Scams Against Older Adults Advisory Group. The advisory group focused on four main areas, and each area was led by a separate committee: (1) expanding consumer education and outreach efforts, (2) improving industry training on scam prevention, (3) identifying innovative or high-tech methods to detect and stop scams, and (4) reviewing research related to scam prevention messaging and making recommendations for future research. The advisory group’s work products are available to the public at ftc.gov/olderadults. Additional information about the advisory group’s work is described in the FTC’s annual older adults report. Federal Trade Commission, Protecting Older Consumers 2023-2024.

[9]A national strategy is a type of interagency coordination mechanism—typically, a document or initiative—that provides a broad framework for addressing issues that cut across federal agencies and other levels of government and sectors. We previously identified desirable characteristics for a national strategy. See GAO, Combatting Terrorism: Evaluation of Selected Characteristics in National Strategies Related to Terrorism, GAO‑04‑408T (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 3, 2004).

[10]The Federal Advisory Council, which was created by the Federal Reserve Act, is composed of 12 representatives of the banking industry selected by the Federal Reserve Banks.

[11]The American Bankers Association is an organization that supports bankers and other members of the financial services industry with education, tools, and expert insights. The American Bankers Association also advocates for banks in legislative and regulatory issues.

[12]Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, National Anti-Scam Centre in action: Quarterly update January to March 2024, https://www.nasc.gov.au/system/files/NASC‑Quarterly‑update‑Q3‑2024.pdf.

[13]See GAO, Broadband: National Strategy Needed to Guide Federal Efforts to Reduce Digital Divide, GAO‑22‑104611 (Washington, D.C.: May 31, 2022); and Broadband: A National Strategy Needed to Coordinate Fragmented, Overlapping Federal Programs, GAO‑23‑106818 (Washington, D.C.: May 10, 2023).

[14]Fragmentation refers to those circumstances in which more than one federal agency (or more than one organization in an agency) is involved in the same broad area of national need, and opportunities exist to improve service. Overlap occurs when multiple agencies have similar goals, engage in similar activities or strategies to achieve them, or target similar beneficiaries. See GAO, Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication: An Evaluation and Management Guide, GAO‑15‑49SP (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 14, 2015).

[15]We identified eight federal agencies (of the 13 total agencies in our review) that receive complaints from consumers about scams. These agencies are: CFPB, the FBI, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Federal Reserve, FTC, Homeland Security Investigations, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and Secret Service.

[16]The FBI defines internet crime as any illegal activity involving one or more components of the internet, such as websites, chat rooms, and email. Internet crime involves the use of the internet to communicate false or fraudulent representations to consumers. According to the FBI, these crimes may include, but are not limited to, advance-fee schemes, business email compromise, computer hacking, confidence/romance scams, employment/business opportunity scams, government impersonation scams, identity theft, investment scams, lottery/sweepstakes/inheritance scams, nondelivery of goods or services, and tech support scams.

[17]The FBI does not provide fraud or scam subcategories, such as imposter scams, that consumers can select from when making complaints. Because IC3 does not request information from consumers about the type of internet crime they encountered in a predetermined data field, it relies on consumers to include this information in an open narrative field. According to FBI officials, analysts review IC3 complaints to determine the crime type and actual dollar losses based on the information provided by the consumer.

[18]United States Attorney’s Office, Western District of Washington, Financial Fraud Crime Victims, https://www.justice.gov/usao-wdwa/victim-witness/victim-info/financial-fraud.

[19]The Better Business Bureau accepts complaints about scams, misleading advertisements, identity theft, and other marketplace issues involving any business. Mass-market consumer fraud refers generally to any fraud scheme that uses one or more mass-communication methods, such as the internet, telephones, mail, or in-person meetings, to fraudulently solicit or transact with numerous prospective victims, or to transfer fraud proceeds to financial institutions or others connected with the scheme. Keith B. Anderson, To Whom Do Victims of Mass-Market Consumer Fraud Complain? (May 24, 2021), available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3852323, or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3852323.

[20]FTC estimates that overall consumer loss from fraud, adjusting for underreporting, was as high as $158.3 billion. Federal Trade Commission, Protecting Older Consumers 2023-2024 (Oct. 2024).

[21]In September 2023, the work group published an operational definition of scams and, in June 2024, introduced a Scam Classifier Model. The definition defines scams as the use of deception or manipulation intended to achieve financial gain. Federal Reserve Board officials told us that CFPB, the FBI, and FTC were not part of this work group and that the officials did not know what those agencies’ views would be on this definition. This definition has not been adopted throughout the government.

[22]GAO, Homeland Security: Progress Made; More Direction and Partnership Sought, GAO‑02‑490T (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 12, 2002).

[23]FTC, Protecting Older Consumers 2023–2024 (Oct. 18, 2024) https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/federal‑trade‑commission‑protecting‑older‑adults‑report_102024.pdf.