U.S. CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGRATION SERVICES

Implementing GAO’s Recommendations Would Help Manage Fraud Risks in Immigration Benefit Programs

Statement of Rebecca Gambler, Chief Quality Officer, Audit Policy and Quality Assurance

Before the Subcommittee on Border Security and Immigration, Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. Senate

For Release on Delivery Expected at 2:30 p.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights

A testimony before the Subcommittee on Border Security and Immigration, Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. Senate

For more information, contact: Rebecca Gambler at GamblerR@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Each year, the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) processes millions of applications and petitions for persons seeking to visit or reside in the U.S. or become citizens. USCIS's Fraud Detection and National Security Directorate (FDNS) leads the agency’s efforts to combat fraud. In September 2022, GAO reported that USCIS could better ensure its antifraud efforts are effective and efficient by taking a strategic and risk-based approach that aligns with leading practices in three areas of GAO’s Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (see figure).

Specifically, GAO found that USCIS had conducted fraud risk assessments for a small number of specific immigration benefits, but did not have a process for regularly conducting those assessments. In addition, GAO reported that FDNS had not developed an antifraud strategy to guide the design and implementation of antifraud activities, as well as the allocation of resources to respond to its highest-risk areas. GAO also found that FDNS had not evaluated its antifraud activities for efficiency and effectiveness. Taking action to implement these leading practices will help USCIS ensure that it is effectively preventing, detecting, and responding to potential fraud.

USCIS Should Take Action in Key Areas to Manage Fraud Risks

In December 2025, GAO reported that from May 2022 through September 2024, about 774,000 noncitizens were granted parole—temporary permission to stay in the U.S.—across three humanitarian parole processes for noncitizens with U.S.-based supporters. These processes included Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans; Uniting for Ukraine; and family reunification parole. USCIS was responsible for reviewing supporter applications for evidence they had sufficient financial means to support prospective parole beneficiaries and met other requirements. In early 2024, FDNS officials analyzed 2.6 million supporter applications and found that fraud risks were widespread in Uniting for Ukraine and Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans parole processes. For example, fraud indicators included supporter information belonging to deceased individuals and thousands of applications with at least one piece of fictitious supporter information. USCIS attributed the fraud risks to insufficient internal controls in its supporter vetting process—for example, not having automated processes to prevent or detect possible fraudulent activity. DHS has since suspended or terminated the processes. However, GAO found that USCIS has not developed an internal control plan for new or changed programs in the future. Such a plan could include basic antifraud controls and mechanisms to help proactively identify and mitigate fraud risks.

Why GAO Did This Study

Granting immigration benefits to individuals with fraudulent claims can jeopardize the integrity of the immigration system by enabling individuals to remain in the U.S. and potentially apply for certain federal benefits or pursue a path to citizenship.

In 2022 and 2023, DHS introduced new processes for humanitarian parole in response to increases in noncitizens arriving at the southwest border. The processes allowed eligible noncitizens from certain countries to travel to the U.S. to seek a grant of parole. To be eligible, noncitizens had to have a U.S.-based supporter apply to financially support them. As of December 2025, DHS had suspended or terminated the processes.

This statement discusses USCIS efforts to manage fraud risks (1) across immigration benefits it adjudicates and (2) in humanitarian parole processes for noncitizens with U.S.-based supporters. This statement is based primarily on our September 2022 and December 2025 reports on these topics.

What GAO Recommends

GAO made recommendations to USCIS in the two reports covered by this statement to improve the agency’s fraud risk management. These include implementing processes to (1) conduct regular fraud risk assessments, (2) develop an antifraud strategy, and (3) conduct risk-based evaluations of the effectiveness of antifraud activities, and developing an internal control plan that can be applied to a new or changed program. DHS concurred with these recommendations and identified planned or ongoing steps to address them.

Chairman Cornyn, Ranking Member Padilla, and Members of the Subcommittee:

I am pleased to be here today to discuss our work on U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services’ (USCIS) efforts to manage fraud risks related to immigration benefits. Within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), USCIS processes millions of applications and petitions each year for persons seeking to visit the U.S. for study, work, or other temporary activities; reside in the U.S. on a permanent basis; or become U.S. citizens.[1] To ensure the integrity of the immigration system, USCIS reviews applications and petitions to identify potential fraud, national security, or public safety concerns.

USCIS’s Fraud Detection and National Security Directorate (FDNS) is tasked with leading efforts to combat fraud, among other things. For example, FDNS investigates concerns that the marriages that form the basis of family-based immigration benefits are not bona fide, or that international students are not meeting attendance criteria to maintain their status.

We have previously reported on USCIS’s efforts to manage fraud risks, both across immigration benefits and for specific processes and benefit types. In September 2022, we reported on USCIS’s agency-wide fraud detection operations for the immigration benefits it adjudicates, including its efforts to assess fraud risks, develop an antifraud strategy, and evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of its antifraud activities.[2] In December 2025, we reported on fraud risks in humanitarian parole processes that allowed noncitizens with U.S.-based financial supporters to enter and stay in the U.S. temporarily.[3] Further, we have reported on USCIS’s efforts to manage fraud in benefit programs, including, for example, in programs for immigrant investors and victims of domestic abuse.[4] In these reports we made recommendations to USCIS to improve its fraud risk management. USCIS has implemented some of these recommendations but has not yet implemented others, as discussed further below.

My statement today discusses USCIS efforts to manage fraud risks (1) across immigration benefits it adjudicates and (2) in humanitarian parole processes for noncitizens with U.S.-based supporters. This statement is based primarily on our September 2022 and December 2025 reports on these topics, as well as information on actions USCIS has taken in response to our recommendations.[5] For these reports, we analyzed USCIS data and documentation, such as standard operating procedures and user guides related to antifraud activities. We also interviewed officials from USCIS headquarters and field locations, including FDNS officials and officials responsible for reviewing applications to financially support prospective parole beneficiaries. More detailed information on the objectives, scope, and methodology can be found in the reports.

We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Immigration Benefit Fraud

Immigration benefit fraud is the act of willfully or knowingly misrepresenting material facts to obtain an immigration benefit for which the individual would otherwise be ineligible.[6] Benefit fraud can occur in a number of ways, and is often facilitated by document fraud (e.g., submitting falsified affidavits or making other materially false written statements in an immigration form or supporting document) and identity fraud (i.e., fraudulent use of others’ valid documents).[7] Fraud in the immigration context may result in various statutory violations.[8]

Applicants and petitioners may act alone to perpetrate fraud, or a third party may prepare and file fraudulent documents, written statements, or supporting details—often in exchange for a fee—with or without the applicant’s knowledge or involvement. Third parties include attorneys, form preparers, interpreters, and individuals posing in one of those roles to engage in unauthorized practice of immigration law. Attorney fraud and unauthorized practice of immigration law fraud are often associated with large-scale fraud schemes, in which one or multiple attorneys file fraudulent forms on behalf of hundreds or thousands of applicants or petitioners.

USCIS may deny a benefit request upon determining that the individual is not eligible for approval by a preponderance of evidence, due to fraud material to the adjudication process.[9]

Types of immigration benefit fraud include:

· Marriage fraud. Knowingly entering a marriage for the purpose of evading any provision of immigration law.[10]

· Family relation fraud. Falsely claiming a relationship other than marriage—such as a parent-child or sibling relationship—for the purpose of evading any provision of immigration law.

· Employment fraud. Willfully misrepresenting material facts related to employment. Such fraud may be perpetrated by beneficiaries—who may misrepresent their qualifications or submit falsified supporting documents to USCIS—or by petitioning employers, who may create fabricated positions, misrepresent their ability to pay the beneficiary, or create shell organizations for the purpose of perpetrating immigration fraud.

Fraud Risk Framework

The objective of fraud risk management is to ensure program integrity by continuously and strategically mitigating the likelihood and effects of fraud. Executive branch agency managers are responsible for managing fraud risks and implementing practices for combating those risks. In 2015, we issued A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (Fraud Risk Framework), a comprehensive set of leading practices that serves as a guide for combating fraud in a strategic, risk-based manner.[11]

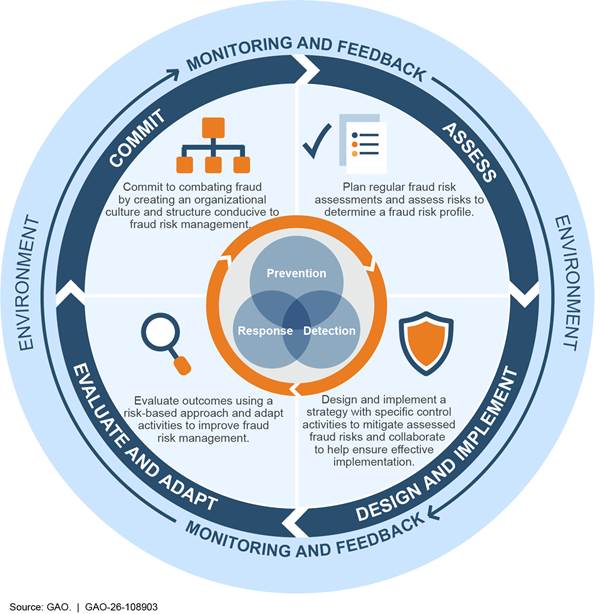

The framework describes leading practices for (1) establishing an organizational structure and culture that are conducive to fraud risk management; (2) assessing fraud risks; (3) designing and implementing antifraud activities to prevent and detect potential fraud; and (4) monitoring and evaluating antifraud activities to help ensure they are effectively preventing, detecting, and responding to potential fraud. Office of Management and Budget guidelines, and related agency controls, developed pursuant to the Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015, which remain in effect according to the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019, incorporate the leading practices of the Fraud Risk Framework.[12] Figure 1 summarizes the Fraud Risk Framework.

Figure 1: GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework

USCIS Has Not Yet Implemented Recommendations to Better Manage Fraud Risks Across Immigration Benefits

In September 2022, we reported that USCIS could better ensure its antifraud efforts are effective and efficient by taking a more strategic and risk-based approach to managing fraud risks across immigration benefits it adjudicates.[13] We made six recommendations to USCIS. The agency has implemented one of the recommendations and has taken steps toward addressing the other five but has not yet fully implemented them.[14] Detailed descriptions of these recommendations are contained in our report.

Conducting Fraud Risk Assessments

In September 2022, we reported that USCIS had conducted fraud risk assessments for a small number of specific immigration benefits, but did not plan to conduct additional assessments.[15] The Fraud Risk Framework calls for an agency’s designated antifraud entity to lead fraud risk assessments at regular intervals, and when the program or its operating environment change. According to these leading practices, effective fraud risk assessments generally include: (1) a comprehensive identification of the fraud risks the program faces; (2) an assessment of the likelihood and impact of the fraud risks on the program’s objectives; (3) a determination of the organization’s tolerance for fraud risks in the context of its other operational objectives—for USCIS, effectively and efficiently adjudicating applications; (4) an examination of the effectiveness of existing antifraud activities and a prioritized list of the fraud risks that are not sufficiently addressed; and (5) documentation of the key findings and conclusions in a fraud risk profile for the program.[16]

We recommended USCIS develop and implement a process—including clearly defining roles and responsibilities—for regularly conducting fraud risk assessments and documenting fraud risk profiles for the immigration benefits USCIS is responsible for adjudicating. USCIS concurred with our recommendation. In August 2023, USCIS reported it had completed draft documentation outlining a framework for how USCIS will conduct fraud risk assessments and develop fraud risk profiles, and convened a working group to review, edit, and validate the framework. In May 2025, USCIS reported the draft framework was undergoing leadership review. However, in October 2025, USCIS reported that it was creating a new risk unit within FDNS and, in February 2026, USCIS stated that it was still determining how the new unit will conduct fraud risk assessments and develop associated fraud risk profiles. USCIS expects to address this recommendation by June 2026.

Developing an Antifraud Strategy

In September 2022, we reported that FDNS had not developed an antifraud strategy to guide the design and implementation of antifraud activities, as well as the allocation of resources to respond to its highest-risk areas. According to the Fraud Risk Framework, organizations that are effective at managing fraud risks use the information from their fraud risk assessments and the resulting profiles to develop and document an antifraud strategy.[17] An antifraud strategy is to include: (1) the roles and responsibilities of those involved; (2) a description of existing antifraud activities for preventing, detecting, and responding to fraud, as well as the monitoring and evaluation of those activities; (3) the timelines for implementing additional antifraud activities, as appropriate, and monitoring and evaluations of those activities; (4) how antifraud activities are linked to the highest-priority fraud risks outlined in the program’s fraud risk profile; and (5) the value and benefits of the antifraud activities so the strategy can be communicated to employees and stakeholders. When developing the antifraud strategy, organizations should consider the costs and benefits of antifraud activities.

We recommended that USCIS develop and implement a process for developing and regularly updating an antifraud strategy that is aligned to the agency’s fraud risk assessments. USCIS concurred with our recommendation. In March 2023, USCIS reported it had drafted an antifraud strategy based on the GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework and fraud risk assessment principles set forth by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners and that the strategy was undergoing leadership review. In February 2026, USCIS stated that it would revise its plans to develop an antifraud strategy due to its reorganization of FDNS. USCIS expects to address this recommendation by June 2026.

Evaluating Antifraud Activities

In September 2022, we reported that FDNS had not evaluated its antifraud activities for effectiveness and efficiency, as called for in the Fraud Risk Framework. The Fraud Risk Framework states that periodic evaluations—that is, the systematic and in-depth study of individual antifraud activities to assess their performance and progress toward strategic goals—can provide assurances that antifraud activities are effective and efficient.[18] These leading practices note that evaluations should be risk based, in that they consider identified risks, emerging risks, and internal and external factors that affect the operating environment. The information gathered from these evaluations is critical for making evidence-based decisions about allocating resources and adapting the design and implementation of antifraud activities to improve outcomes.

We recommended USCIS develop and implement a process—including clearly defining roles and responsibilities—for conducting risk-based evaluations of the effectiveness and efficiency of antifraud activities. USCIS concurred with our recommendation and also acknowledged the need to implement the recommendations to develop fraud risk assessments and an antifraud strategy prior to evaluating the effectiveness of antifraud activities. In February 2026, USCIS stated that it was revising its plans to address this recommendation and expects to complete its efforts by September 2026.

Granting immigration benefits to individuals with fraudulent claims can jeopardize the integrity of the immigration system by enabling individuals to remain in the U.S. and potentially apply for certain federal benefits or pursue a path to citizenship. We continue to believe that implementing these recommendations will help USCIS ensure that it can effectively prevent, detect, and respond to potential fraud.

USCIS Identified Fraud Risks in Humanitarian Parole Processes for Noncitizens but Has Not Developed a Plan for Internal Controls

In December 2025, we reported that USCIS had identified fraud risks in humanitarian parole processes for noncitizens with U.S.-based supporters.[19] These processes have since been suspended or terminated; however, USCIS has not developed a plan it could use in the future to help proactively mitigate fraud risk and other risks in new or changed programs.

In 2022 and 2023, in response to increases in noncitizens arriving at the southwest border, DHS introduced new processes that allowed eligible noncitizens from certain countries to travel to the U.S. to seek a grant of parole, providing them temporary permission to stay in the U.S. The three processes included: (1) Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans (CHNV), (2) Uniting for Ukraine, and (3) family reunification parole. Our analysis of DHS data found that, from May 2022 when DHS began granting parole with these new processes through September 2024, DHS granted parole to about 774,000 noncitizens across them.

USCIS was responsible for reviewing supporter applications to determine whether they included sufficient evidence that the supporter had the means to financially support the prospective beneficiary and met other requirements (known as a confirmation).[20] If USCIS confirmed the application, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) was responsible for vetting the prospective beneficiary, determining whether to authorize them to travel to the U.S., and considering them for a discretionary grant of parole upon their arrival.

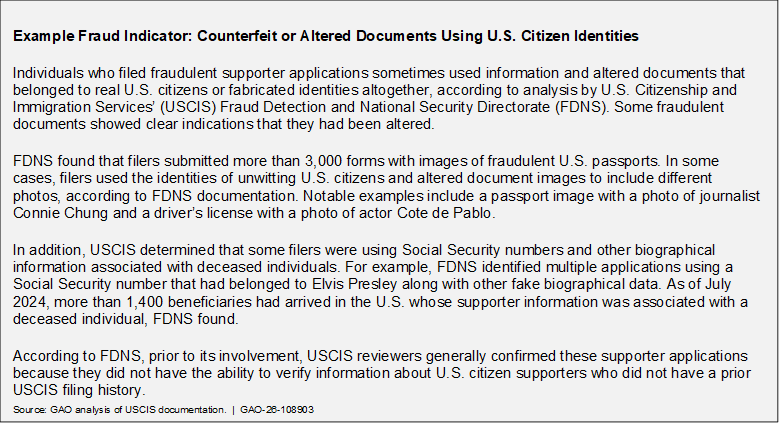

Shortly after the processes began, in fall 2022, FDNS began receiving referrals of potential fraud from CBP and from within USCIS related to the processes. In early 2024, FDNS officials analyzed 2.6 million supporter applications and found that fraud indicators were widespread in Uniting for Ukraine and CHNV. For example, fraud indicators among the applications included supporter information belonging to deceased individuals, counterfeit or altered documents, and thousands of applications with at least one piece of fictitious supporter information. The analysis also showed that applications included Social Security numbers, phone numbers, physical addresses, and email addresses that had been used hundreds of times.[21] DHS suspended the CHNV and Uniting for Ukraine processes in July 2024 due to the fraud risks and subsequently terminated CHNV in March 2025.[22]

As we reported in December 2025, USCIS assessments attributed the risks identified in the parole processes to insufficient internal control activities in the supporter application process. Antifraud control activities include automated features in data systems to prevent and detect fraudulent activity. However, according to a July 2024 USCIS report, its case management system lacked such functionality, which, for example, allowed some applicants to create multiple USCIS accounts with slightly different biographic information. The USCIS report also found that limitations in USCIS access to information to review supporter information contributed to the vulnerabilities. These included limited access to databases to fully vet supporter criminal history and verify the identities of U.S. citizens.

As a result of the lack of sufficient internal controls in the CHNV and Uniting for Ukraine processes, some individuals perpetrated scams that exploited prospective beneficiaries and stole the identities of U.S. citizens. For example, some filers submitted supporter applications with fraudulent and incomplete information solely for the purpose of exacting a fee from the prospective beneficiaries—rather than to establish their ability to serve as supporters. In addition, USCIS confirmed some supporters despite them not being eligible, for example those with fictitious biographical information or prior criminal activity.

We concluded that, although DHS has ended the supporter-based parole processes, USCIS could still benefit from having an internal control plan in place for future situations that may introduce new or increased fraud risks. We recommended that USCIS develop an internal control plan that can be immediately implemented or quickly tailored to mitigate fraud risks in a new program or a change to an existing program, such as a new immigration benefit application.[23] For example, a preexisting internal control plan might include basic antifraud controls and other steps to ensure managers are considering fraud risks before implementing a new program or changing an existing program. DHS concurred and stated it would take steps to develop such a plan by September 2026.

Chairman Cornyn, Ranking Member Padilla, and Members of the Subcommittee, this completes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions that you may have at this time.

GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact Rebecca Gambler, Chief Quality Officer, Audit Policy and Quality Assurance at GamblerR@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement. GAO staff who made key contributions to this statement are Ashley Davis (Assistant Director), Jessica Wintfeld (Analyst in Charge), Heather Dunahoo, Michele Fejfar, Taylor Matheson, Sasan J. “Jon” Najmi, and Heidi Nielson. Other staff who made key contributions to the reports cited in the testimony are identified in the source products.

Related GAO Products

Humanitarian Parole: DHS Identified Fraud Risks in Parole Processes for Noncitizens and Should Assess Lessons Learned. GAO‑26‑107433. Washington, D.C.: December 11, 2025.

Immigrant Investor Program: Opportunities Exist to Improve Fraud and National Security Risk Monitoring. GAO‑23‑106452. Washington, D.C.: March 28, 2023.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services: Additional Actions Needed to Manage Fraud Risks. GAO‑22‑105328. Washington, D.C.: September 19, 2022.

Nonimmigrant Investors: Actions Needed to Improve E-2 Visa Adjudication and Fraud Coordination. GAO‑19‑547. Washington, D.C.: July 17, 2019.

Immigration Benefits: Additional Actions Needed to Address Fraud Risks in Program for Foreign National Victims of Domestic Abuse. GAO‑19‑676. Washington, D.C.: September 30, 2019.

Refugees: Actions Needed by State Department and DHS to Further Strengthen Applicant Screening Process and Assess Fraud Risks. GAO‑17‑706. Washington, D.C.: July 31, 2017.

Asylum: Additional Actions Needed to Assess and Address Fraud Risks. GAO‑16‑50. Washington, D.C.: December 02, 2015.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

David A. Powner, Acting Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]In general, an immigration “petition” is filed, using the appropriate form, by persons requesting an immigration benefit for themselves or a foreign relative, or by a U.S.-based entity requesting a benefit on behalf of an employee (beneficiary), to establish eligibility for classification as an immigrant with a path to lawful permanent residence, or as a nonimmigrant for an authorized period of stay. For petition-based categories, an approved petition then allows an individual in the U.S. to submit an “application,” using the appropriate form, to USCIS for permanent or temporary immigration status. For non-petition categories, a U.S.-located individual may also submit an application for immigration status. An individual located abroad would need a visa application to be approved by the Department of State to authorize them to travel to the U.S. and seek admission at a port of entry under the requested immigration status, whether or not the benefit category is petition based. An immigrant is a foreign national seeking permanent status in the U.S. under 8 U.S.C. ch. 12, subch. II (Immigration); and a nonimmigrant is a foreign national seeking temporary status in the U.S. under one of the classes of nonimmigrants defined in 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(15).

[2]GAO, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services: Additional Actions Needed to Manage Fraud Risks, GAO‑22‑105328 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 19, 2022).

[3]GAO, Humanitarian Parole: DHS Identified Fraud Risks in Parole Processes for Noncitizens and Should Assess Lessons Learned, GAO‑26‑107433 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 11, 2025). Statute defines an “alien” as any person who is not a citizen or national of the U.S. 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(3). DHS documentation we reviewed for our December 2025 report used the terms “alien,” “migrant,” and “noncitizen” interchangeably. For readability, we generally use the term “noncitizen,” except when quoting language in statute, regulation, or executive orders that used the term “alien.” The Homeland Security Act of 2002 provides the Secretary of Homeland Security with the authority, under the Immigration and Nationality Act, to parole noncitizens, on a case-by-case basis, into the U.S. temporarily for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit. 6 U.S.C. §§ 251, 557; 8 U.S.C. § 1182(d)(5)(A). Pursuant to this authority, DHS may set the duration of the parole and DHS officials may terminate parole in accordance with DHS regulations. See 8 C.F.R. § 212.5. The Secretary of Homeland Security has delegated parole authority to agencies in the department including USCIS and U.S. Customs and Border Protection. As of December 2025, DHS had terminated or suspended the humanitarian parole processes we examined and the termination of many of these processes were the subject of ongoing litigation. See, e.g., Doe v. Noem, 152 F.4th 272 (Sept. 12, 2025).

[4]GAO, Immigrant Investor Program: Opportunities Exist to Improve Fraud and National Security Risk Monitoring, GAO‑23‑106452 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 28, 2023) and Immigration Benefits: Additional Actions Needed to Address Fraud Risks in Program for Foreign National Victims of Domestic Abuse, GAO‑19‑676 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 30, 2019).

[6]Such material misrepresentations may or may not involve a specific intent to deceive, but for FDNS’s purposes, that intent is required to make a finding of fraud.

[7]Under 8 U.S.C. § 1324c, immigration-related document fraud includes forging, counterfeiting, altering, or falsely making any document, or using, accepting, or receiving such falsified documents in order to satisfy any requirement of, or to obtain a benefit under the Immigration and Nationality Act.

[8]See, e.g., 18 U.S.C. ch. 47 (fraud and false statements), in particular § 1001 (criminal penalties for false statements and concealment before any U.S. government entity); 18 U.S.C. §§ 1541–1547 (criminal penalties for immigration-related fraud); 18 U.S.C. § 1621 (criminal penalties for perjury); 8 U.S.C. §§ 1182(a)(6)(C)(i), (a)(6)(F), 1227(a)(1)(A), (a)(1)(B), (a)(3)(C)(i) (grounds of removability for fraud or willful misrepresentations), 1324c (civil penalties for immigration-related document fraud and criminal penalties for not disclosing one’s role as document preparer).

[9]See 8 C.F.R. pts. 103 (subpt. A), 205. USCIS may also revoke approval of a petition, terminate certain types of status, and rescind adjustment to lawful permanent resident status due to fraud, subject to relevant legal criteria.

[10]See 8 U.S.C. § 1325(c).

[11]GAO, A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, GAO‑15‑593SP (Washington, D.C.: July 2015).

[12]The Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015, enacted in June 2016, required the Office of Management and Budget, in consultation with the Comptroller General of the United States, to establish guidelines for federal agencies to establish financial and administrative controls to identify and assess fraud risks and to design and implement antifraud control activities in order to prevent, detect, and respond to fraud, including improper payments. Pub. L. No. 114-186, § 3, 130 Stat. 546, 546-47 (2016). The act further required these guidelines to incorporate the leading practices from the Fraud Risk Framework. Although the Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015 was repealed in March 2020 by the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019, this 2019 act stated that these guidelines shall remain in effect, and may be periodically modified by the Office of Management and Budget, consulting with GAO, as the Director and Comptroller General deem necessary. Pub. L. No. 116-117, §§ 2(a), 3(a)(4), 134 Stat. 113, –131-133 (2020) (codified at 31 U.S.C. §§ 3321 note, 3357). In its 2016 Circular No. A-123 guidelines, OMB directed agencies to adhere to the Fraud Risk Framework’s leading practices. Office of Management and Budget, Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control, OMB Circular No. A-123 (Washington, D.C.: July 15, 2016).

[14]In addition to the recommendations discussed below, we made two recommendations related to improving USCIS’s process for estimating FDNS staffing needs, one of which USCIS has implemented. Specifically, USCIS implemented our recommendation to develop and implement additional guidance on FDNS data entry practices for fields used as staffing model inputs to ensure consistency and produce quality and reliable data. USCIS has not yet implemented our recommendation to identify the factors that affect FDNS’s workload to ensure the staffing model’s assumptions reflect operating conditions. We also recommended that USCIS develop outcome-oriented performance metrics, including baselines and targets as appropriate, to monitor the effectiveness of its antifraud activities, and USCIS has not yet implemented that recommendation.

[15]Specifically, USCIS completed assessments of fraud risk for the EB-5 Immigrant Investor Program in 2018, affirmative asylum benefits in 2021, and Violence Against Women Act self-petitions in 2021. USCIS conducted all three of those assessments in response to recommendations we made about these benefit types.

[18]GAO‑15‑593SP and GAO, Designing Evaluations: 2012 Revision, GAO‑12‑208G (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 13, 2012). GAO recently issued a supplement to the Fraud Risk Framework to help agencies better evaluate the effectiveness of their fraud risk management activities; GAO, Combating Fraud: Approaches to Evaluate Effectiveness and Demonstrate Integrity, GAO‑26‑107609 (Washington, D. C.: Jan. 14, 2026).

[20]According to USCIS officials, the agency referred to its review process as a confirmation and not an approval because USCIS was not conferring any immigration benefit to a supporter or beneficiary. U.S. Customs and Border Protection decided whether to grant parole in subsequent steps in the process.

[21]Separately, CBP’s National Targeting Center conducted a review of confirmed CHNV supporter information and found instances of supporters with a criminal history. The center first reviewed a subset of supporters of Venezuelan beneficiaries by vetting their information against information on national security and public safety threats. It found that about 25 percent of the supporters were potential matches against this information. Upon manual review, about 18 percent of the supporter subset were found to be true matches, meaning that CBP likely would have found the beneficiary not eligible for parole had the information about the supporter been known during the review process, according to the center.

[22]Additionally, DHS suspended the family reunification parole process in January 2025.

[23]In the report, we also recommended that DHS assess and document lessons learned from the supporter-based parole processes that are relevant to other ongoing operations and apply the lessons learned identified through the assessment to ongoing operations, as appropriate. DHS did not concur with these recommendations, noting terminating the processes sufficiently addresses the challenges. We believe these recommendations remain valid and could help improve other areas of DHS operations beyond parole.