COVID-19

Lessons Can Help Agencies Better Prepare for Future Emergencies

Report to Congressional Committees

August 2024

GAO‑24‑107175

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑24‑107175. For more information, contact Jessica Farb at (202) 512-7114 or FarbJ@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑24‑107175, a report to congressional committees

August 2024

COVID-19

Lessons Can Help Agencies Better Prepare for Future Emergencies

Why GAO Did This Study

The COVID-19 pandemic brought significant challenges to the nation's public health and economy. Since March 2020, Congress has provided about $4.65 trillion in federal funds to help the nation respond to and recover from the pandemic. Agencies across the government have worked to implement the federal response.

The CARES Act includes a provision for GAO to report regularly on the public health and economic effects of the pandemic and the federal response. This report includes updates on the public health effects and economic conditions since the pandemic, including updates on federal COVID-19 relief funding. It also describes lessons learned from the pandemic that could help federal agencies better prepare for future emergencies.

To describe lessons learned for federal agencies, GAO analyzed issued GAO reports. GAO also collected information on agency actions to address GAO COVID-19 recommendations.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making one new recommendation to the Department of the Treasury to include key lessons from the COVID-19 emergency financial assistance provided to the aviation industry in its efforts to compile resources to prepare for future financial disasters. A Treasury official told us that Treasury agrees with our recommendation and will take steps to implement it.

What GAO Found

The nation continues to recover from the public health and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, COVID-19 was the tenth leading cause of death in 2023, as compared to being the third leading cause of death in 2020 and 2021. Available data also show that inflation declined between March 2023 and March 2024, but remained higher than pre-pandemic levels.

GAO identified lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic that could help federal agencies better prepare for, respond to, and recover from future emergencies. These lessons draw on GAO’s COVID-19 oversight work, which includes 428 recommendations to federal agencies and 24 matters for congressional consideration as of April 2024. Of these recommendations, 220 remain open. Moreover, these recommendations include those related to the three areas GAO added to its High Risk List during the COVID-19 public health emergency:

1. the Department of Health and Human Services’ leadership and coordination of public health emergencies,

2. the Department of Labor’s Unemployment Insurance system, and

3. the Small Business Administration’s emergency loans to small businesses.

Agencies across the government could improve their preparedness for future emergencies by fully implementing GAO’s recommendations.

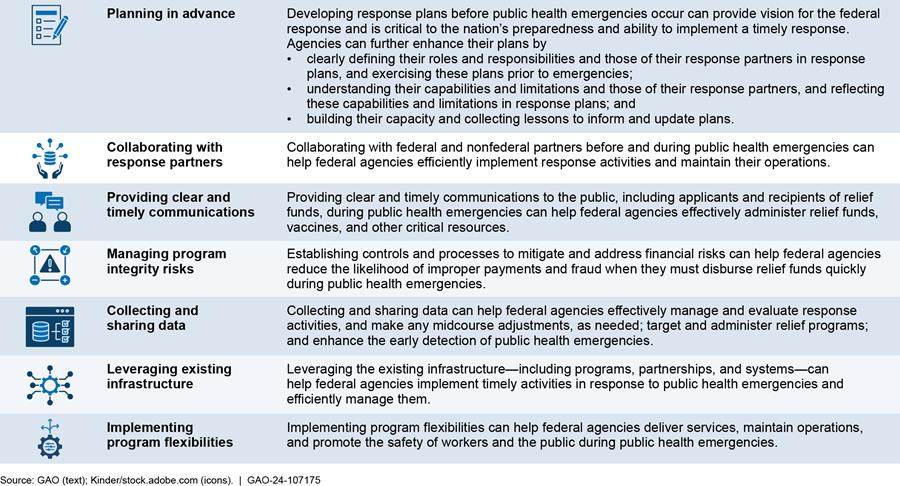

Lessons that could help federal agencies better prepare for future emergencies fall into seven topic areas. These lessons highlight instances where government agencies did well in responding to the pandemic, as well as instances where the government response could have been much better.

|

|

PLANNING IN ADVANCE Advanced plans—including national-level strategies and department- and agency-level plans—provide vision for how the federal government will respond to public health emergencies and are critical to the nation’s preparedness and ability to implement a timely response. Agencies can further enhance their preparedness by · clearly defining their roles and responsibilities and those of their response partners in response plans, and exercising these plans prior to emergencies; · understanding their capabilities and limitations and those of their response partners, and reflecting these capabilities and limitations in response plans; and · building their capacity and collecting lessons to inform and update plans. GAO found instances where federal agencies could improve their preparedness by taking such steps. For example, the Department of the Treasury has not incorporated lessons GAO identified from the COVID-19 assistance programs to the aviation industry into its efforts to compile resources to prepare for future financial disasters. Taking such steps could help Treasury make timely decisions and avoid encountering past challenges when responding to future emergencies. Further, GAO has made recommendations to federal agencies to improve their emergency response plans. For example, GAO recommended that the Department of Health and Human Services develop plans outlining steps to mitigate shortages in needed medical supplies, develop a comprehensive testing strategy, and develop an approach for assessing and addressing known challenges and future risks associated with advanced development and manufacturing of medical countermeasures, including vaccines. |

Source: GAO (text); Kinder/stock.adobe.com (icons). | GAO‑24‑107175

|

|

COLLABORATING WITH RESPONSE PARTNERS Collaborating with response partners—including federal and nonfederal partners—before and during public health emergencies can help agencies efficiently implement response activities and continue operations. Federal agencies can facilitate this collaboration by identifying partners key to implementing the response, regularly coordinating with identified partners, and ensuring partners understand their roles and responsibilities in implementing the response. GAO has made recommendations to agencies across the federal government to improve their collaboration with response partners. For example, GAO recommended that the Department of Health and Human Services share its plans to mitigate medical supply shortages with response partners and maintain up-to-date guidance for partners on requesting and receiving assets from the Strategic National Stockpile. |

Source: GAO (text); Kinder/stock.adobe.com (icons). | GAO‑24‑107175

|

|

PROVIDING CLEAR AND TIMELY COMMUNICATIONS Federal agencies can enhance their efforts to effectively administer relief funds, vaccines, and other critical resources during a public health emergency by providing clear and timely information to · applicants and eligible entities of federal relief funds, · recipients of federal relief funds, and · the public. GAO has made recommendations to federal agencies to improve their communications during public health emergencies. For example, GAO recommended that the Small Business Administration develop a comprehensive strategy for communicating with potential and actual program applicants in the event of an emergency. GAO stated that its strategy should include guidelines for the types of information and timing of information to be provided to program participants throughout an emergency. |

Source: GAO (text); Kinder/stock.adobe.com (icons). | GAO‑24‑107175

|

|

MANAGING PROGRAM INTEGRITY RISKS Establishing controls and processes can help federal agencies manage program integrity risks when they must disburse emergency relief funds quickly during an emergency. Specifically, prepayment controls and processes can help agencies minimize the likelihood of improper payments and fraud. Further, postpayment controls and processes can help agencies identify and recover improper and fraudulent payments when the quick disbursement of funds makes prepayment controls difficult to apply fully. GAO has made recommendations to federal agencies to better manage program integrity risks in emergency assistance programs. For example, GAO recommended that the Department of Labor design and implement an antifraud strategy for unemployment insurance programs that is consistent with leading practices outlined in GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework. |

Source: GAO (text); Kinder/stock.adobe.com (icons). | GAO‑24‑107175

|

|

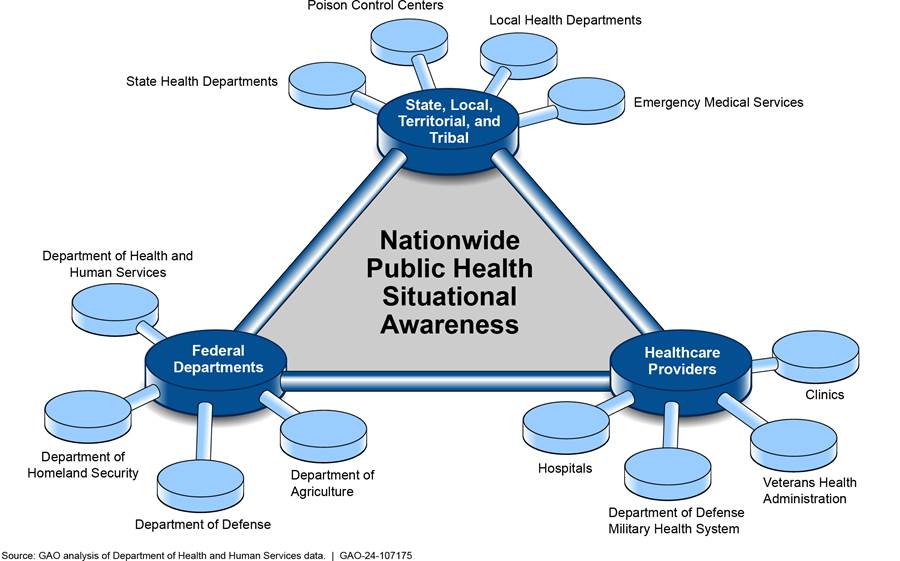

COLLECTING AND SHARING DATA Collecting and sharing data can help federal agencies · effectively manage response activities, evaluate performance in meeting response program goals, and make midcourse adjustments as needed; · target and administer relief fund programs; and · enhance the early detection of public health emergencies. GAO has made recommendations to federal agencies to enhance their ability to collect and share data before and during public health emergencies. For example, GAO recommended that the Department of Health and Human Services develop a plan to establish an electronic nationwide public health situational awareness network and identify measurable steps for completing this network. |

Source: GAO (text); Kinder/stock.adobe.com (icons). | GAO‑24‑107175

|

|

LEVERAGING EXISTING INFRASTRUCTURE Leveraging the existing infrastructure—including programs, partnerships, and systems—can help federal agencies implement timely activities to respond to a public health emergency and efficiently manage them. Specifically, federal agencies can use existing infrastructure to facilitate the delivery of services, distribute federal relief funds, and manage and oversee response programs. GAO identified instances during the COVID-19 pandemic where federal agencies successfully leveraged the existing infrastructure. For example, the Department of the Interior and the Indian Health Service leveraged existing program mechanisms to efficiently distribute COVID-19 relief funds to tribal recipients during the pandemic. GAO has made recommendations to federal agencies to seek such opportunities. Further, GAO suggested that Congress consider enacting automatic increases in federal Medicaid spending during economic downturns to increase federal Medicaid support in a more timely and targeted fashion. |

Source: GAO (text); Kinder/stock.adobe.com (icons). | GAO‑24‑107175

|

|

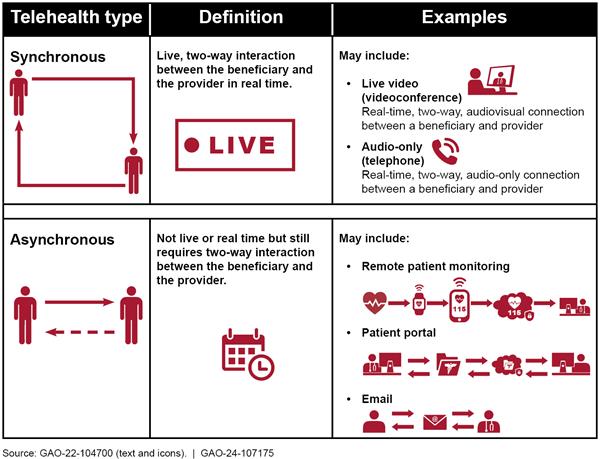

IMPLEMENTING PROGRAM FLEXIBILITIES Implementing flexibilities—such as telehealth and telework—during a public health emergency can help federal agencies · deliver services to program beneficiaries, · maintain activities to support critical operations, and · promote the safety of workers and the public. GAO has recommended that federal agencies examine the extent to which flexibilities utilized during the COVID-19 pandemic could be incorporated in standard operations or used during future emergencies. For example, GAO recommended that the Food and Drug Administration fully assess whether and how alternative tools could help meet drug oversight objectives when in-person inspections are not possible in the future. |

Source: GAO (text); Kinder/stock.adobe.com (icons). | GAO‑24‑107175

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Abbreviations

ASPR Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CFO chief financial officer

CIADM Centers

for Innovation and Advance Development and

Manufacturing

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

CPI Consumer Price Index

DHS Department of Homeland Security

DOD Department of Defense

DOL Department of Labor

DOT Department of Transportation

FDA Food and Drug Administration

FEMA Federal Emergency Management Agency

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

HRSA Health Resources and Services Administration

IRS Internal Revenue Service

OMB Office of Management and Budget

SBA Small Business Administration

SIGPR Office

of the Special Inspector General for Pandemic

Recovery

SLFRF Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds

USDA United States Department of Agriculture

VA Department of Veterans Affairs

VHA Veterans Health Administration

August 1, 2024

Congressional Committees

The COVID-19 pandemic was an unprecedented global crisis resulting in about 1.2 million reported deaths in the U.S. as of April 27, 2024.[1] While the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) terminated the federal public health emergency on May 11, 2023, the nation is still recovering from the public health and economic effects of the pandemic while working to identify and respond to new COVID-19 variants.[2]

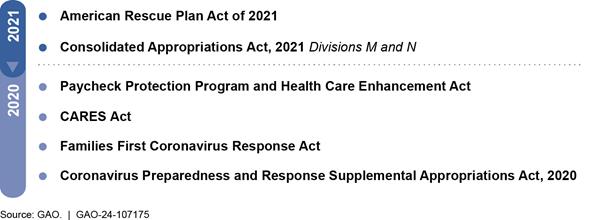

Since March 2020, the CARES Act and five additional laws provided about $4.65 trillion in federal funding to help the nation respond to and recover from the pandemic.[3] The COVID-19 response included a focus on mitigating COVID-19 health risks and providing federal assistance to support individuals and public and private entities. Agencies across the federal government worked to implement this federal response.

The CARES Act includes a provision for GAO to report regularly on the public health and economic effects of the pandemic and the federal response.[4] We have issued 11 comprehensive reports examining the federal government’s continued efforts to respond to and recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, we have issued over 200 standalone reports, testimonies, and science and technology spotlights focused on different aspects of the pandemic.

In our body of work on COVID-19 oversight, we have made 428 recommendations to federal agencies in addition to 24 matters for congressional consideration to improve implementation, oversight, and transparency of the federal response. We also made recommendations to federal agencies to better prepare for future emergencies. As of April 2024, 220 of the recommendations from our COVID-19 oversight work remain open. Federal agencies had fully addressed 198 of these recommendations and partially addressed 35 of these recommendations.[5] Additionally, Congress has taken steps to fully address two matters for congressional consideration.

The 428 recommendations from our COVID-19 oversight work include several we have made to agencies related to the three areas we added to our High Risk List during the COVID-19 public health emergency: (1) HHS’s leadership and coordination of public health emergencies, (2) the Department of Labor’s (DOL) Unemployment Insurance system, and (3) the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) emergency loans to small businesses.[6] For example, we recommended

· HHS should develop a coordinated, department-wide action program that encourages collaboration within HHS and includes external stakeholders involved with the public health response to identify and resolve challenges.[7]

· DOL should develop and implement an antifraud strategy for Unemployment Insurance programs that is consistent with leading practices for preventing, detecting, and responding to fraud outlined in GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework.[8]

· SBA should ensure that it has identified external sources of data that can facilitate the verification of applicant information and the detection of potential fraud across programs, including loans made under the Paycheck Protection Program and the COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan program.[9]

This report includes key data updates on the public health effects and economic conditions following the COVID-19 pandemic and the federal response, including data updates on federal COVID-19 relief funding and spending. It also describes lessons from the pandemic that could help federal agencies better prepare for future emergencies.

To describe lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic that could help federal agencies better prepare for future emergencies, we reviewed and analyzed GAO reports and recommendations, including comprehensive and standalone CARES Act reports. We reviewed additional selected documents, such as a report from the Office of the Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery (SIGPR) on COVID-19 relief funds provided to the aviation industry and public statements from the Department of Justice on federal fraud-related cases involving federal COVID-19 relief programs.[10] We also interviewed officials from the Department of the Treasury and collected information from various federal agencies, including HHS, to identify actions they have taken as of April 2024 to resolve some of our recommendations, such as recommendations from our CARES Act reports.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to August 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Updates to Public Health, Economic, and Federal COVID-19 Relief Funding and Spending Data

Public Health Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic

In our comprehensive reports, we tracked data related to the public health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The following are updates to key data discussed in those reports.

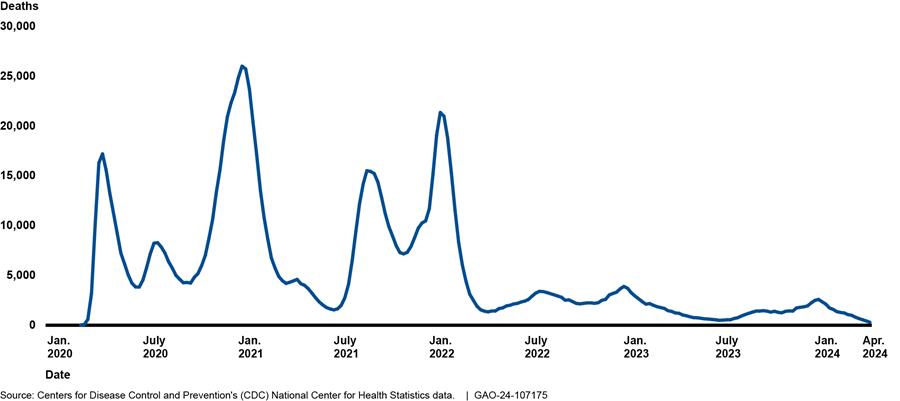

Mortality

Over the course of the pandemic, the U.S. experienced multiple peaks and lulls in the weekly counts of COVID-19-associated deaths—a key indicator of COVID-19 severity—according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics.[11] The highest weekly numbers of COVID-19-associated deaths occurred in January 2021 (with about 26,000 deaths) followed by January 2022 and April 2020. Since mid-2022, weekly COVID-19-associated deaths have been much lower, with the peak in January 2023 reaching about 3,900 deaths, according to the latest available data as of May 1, 2024. See figure 1.

Note: COVID-19-associated deaths are those with COVID-19 listed as an underlying (i.e., primary) or contributing cause of death using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (code U07.1). Data are from CDC WONDER as of May 1, 2024. Death counts for certain weeks prior to March 7, 2020, were suppressed due to small numbers. Data for 2020 and 2021 are final. Data from 2022 through April 2024 are provisional and subject to change.

Likewise, annual rates of COVID-19-associated deaths were higher in 2020 and 2021 than in 2022 and 2023. The rate of COVID-19-associated deaths was about 116.7 deaths per 100,000 U.S. residents in 2020 and peaked at 139.3 in 2021 before falling to 73.7 in 2022 and 22.4 in 2023. COVID-19 was the third leading cause of death in 2020 and 2021, fourth in 2022, and tenth in 2023.[12]

Hospitalizations

Over the course of the pandemic, surges in COVID-19 cases have stressed hospital systems and negatively affected health care and public health infrastructure, according to CDC. Similar to COVID-19-associated deaths, the U.S. experienced peaks and lulls in the level of COVID-19 hospitalizations. At its height in January 2022, the number of adult and pediatric patients with confirmed cases of COVID-19 occupying hospital beds rose to nearly 152,000, with a subsequent peak being much lower. COVID-19 hospitalizations reached approximately 42,000 in January 2023. COVID-19 hospitalizations then fell to just under 5,500 in June 2023 before rising again to approximately 30,600 in January 2024. Since January 2024, COVID-19 hospitalizations have steadily declined and totaled less than 5,000 at the end of April 2024.[13] As of May 1, 2024, hospitals are no longer required to report COVID-19 hospital admissions, among other COVID-19-related indicators, to HHS. However, CDC encourages ongoing, voluntary reporting of hospitalization data.

Long COVID

One public health effect of COVID-19 is long COVID, or post-COVID conditions, which, according to CDC, refers to signs, symptoms, and conditions that continue or develop after an initial COVID-19 infection. According to estimates from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, conducted April 2 through April 29, 2024, about 18 percent of adults in the U.S. aged 18 and older had experienced long COVID, and about 5 percent were experiencing it at the time of the survey.[14] CDC and other researchers have used multiple approaches to estimate how many people experience long COVID. According to CDC, estimates from these different approaches can vary widely depending on factors such as who was included in the study, as well as how and when the study collected information.

Economic Conditions following the COVID-19 Pandemic

In our comprehensive reports, we tracked data related to the economic conditions following the COVID-19 pandemic. The following updates describe selected trends we observed since the pandemic.

The national economy has continued to recover from the economic downturn of early 2020, sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, economic growth has slowed from its 2021 rate, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Real gross domestic product grew by 5.8 percent in 2021, but slowed to 1.9 percent in 2022, 2.5 percent in 2023, and 1.6 percent annual rate in the first quarter of 2024. The increase in the first quarter of 2024 primarily reflected increases in consumer spending, housing and business investment, and state and local government spending. The strength of the national economic recovery will depend on factors such as evolving geopolitical tensions and monetary policy actions.

Based on data covering price trends through March 2024, inflation had declined compared with a year ago but remained elevated compared with pre-pandemic levels.[15] Annual inflation indicators were 2.7 percent or higher in March 2024, which was significantly lower than the 4.2 percent in March 2023.[16] Yet, inflation was still slightly higher than averages of about 2 percent in recent decades.[17]

Indicators of more recent price pressures, including indicators that focus on underlying inflation trends, have increased moderately. Specifically, underlying inflation trends ranged from 0.3 percent to 0.5 percent in January, February, and March 2024.[18] These monthly trends indicate a lack of further progress toward the easing of inflation in recent months.

The labor market has continued to recover from the pandemic, but job growth showed signs of cooling according to DOL data on unemployment and other labor market conditions through March 2024. The unemployment rate remained low at 3.8 percent in March 2024 and was only slightly higher than the 54-year record low of 3.4 percent in January 2023. Meanwhile, both the employment-to-population ratio and labor force participation rate have changed little over the past year and remained lower than in the pre-pandemic period.[19] Additionally, as of March 2024, hiring and job opening rates continued to fall over the past year, suggesting the labor market has gradually cooled.

Federal COVID-19 Relief Funding and Spending

Six laws provided about $4.65 trillion in funding to help the nation respond to and recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. See figure 2.

Note: The COVID-19 relief laws consist of the six laws providing comprehensive relief across federal agencies and programs that the Department of the Treasury uses to record and track COVID-19 relief spending, in accordance with guidance issued by the Office of Management and Budget.

In our comprehensive reports, we presented data tracking how agencies were obligating and expending COVID-19 relief funding. The following are updates to these data as of April 30, 2024, the most recent date for which government-wide information was available at the time of our analysis.

The federal government obligated a total of $4.57 trillion of the $4.65 trillion in COVID-19 relief funding, as reported by federal agencies to Treasury, in accordance with Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance.[20] Further, the federal government had expended about $4.41 trillion of this COVID-19 relief funding. For the top nine spending areas, agencies reported that COVID-19 relief funding obligations totaled $3.69 trillion (81 percent of total obligations), and expenditures totaled $3.61 trillion.[21] Table 1 provides additional details on government-wide COVID-19 relief funding, obligations, and expenditures by major spending areas as of April 30, 2024.

|

Major spending area (dollars in billions) |

COVID-19 relief funding |

Total |

Total |

|

Economic Impact Payments (Department of the Treasury) |

859.8 |

859.3 |

859.3 |

|

Business Loan Programs (Small Business Administration) |

830.0 |

828.1 |

828.0a |

|

Unemployment Insurance (Department of Labor) |

697.9 |

697.5 |

689.0 |

|

Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) (Department of the Treasury) |

350.0 |

349.9 |

349.9b |

|

Public Health and Social Services Emergency Fund (Department of Health and Human Services) |

337.3 |

332.6 |

298.6 |

|

Education Stabilization Fund (Department of Education) |

277.3 |

277.3 |

236.0 |

|

Coronavirus Relief Fund (Department of the Treasury) |

150.0 |

149.9 |

149.8 |

|

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programs (Department of Agriculture) |

121.0 |

98.4 |

102.3c |

|

U.S. Coronavirus Refundable Credits (Department of the Treasury) |

98.8 |

92.2 |

92.2 |

|

Other areas (includes over 300 accounts)d |

927.7 |

883.4 |

803.9 |

|

Totale |

4,649.9 |

4,568.5 |

4,408.9 |

Source: GAO analysis of data from the Department of the Treasury and applicable agencies. | GAO‑24‑107175

Note: COVID-19 relief funding, obligation, and expenditure data shown for the major spending areas are based on data reported by applicable agencies to Treasury’s Governmentwide Treasury Account Symbol Adjusted Trial Balance System. Federal agencies use this system to provide proprietary financial reporting and budgetary execution information to Treasury. These amounts can fluctuate from month to month. COVID-19 relief funding is the cumulative amount of funding provided in the six COVID-19 relief laws that Treasury uses to record and track COVID-19 relief spending, in accordance with Office of Management and Budget guidance. Further, the $4.65 trillion total reflects rescissions of COVID-19 relief funding enacted in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, Pub. L. No. 118-5, 137 Stat. 10, 23-30, div. B, tit. I (2023), and other laws. The most recent date for which government-wide information was available at the time of GAO’s analysis was April 30, 2024.

aThe Small Business Administration’s Business Loan Program account includes activity for Paycheck Protection Program loan guarantees and certain other loan subsidies. These expenditures relate mostly to the loan subsidy costs (i.e., the loan’s estimated long-term costs to the U.S. government).

bMost of the SLFRF funds were allocated to states, the District of Columbia, and local governments. In April 2024, GAO reported that as of September 30, 2023, which was the most recently available data at the time of the report, states and the District of Columbia reported obligating 73 percent ($142.4 billion) and spending 53 percent ($103.7 billion) of their $195.8 billion in SLFRF awards. A total of 26,442 localities—including cities, counties, and smaller localities—reported obligating 64 percent ($80.1 billion) and spending 47 percent ($59.4 billion) of their $126.1 billion in SLFRF awards. See GAO, COVID-19 Relief: State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Spending as of September 30, 2023, GAO‑24‑107472 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 10, 2024).

cDepartment of Agriculture officials told GAO that the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programs spending amounts were not reported to the Governmentwide Treasury Account Symbol Adjusted Trial Balance System correctly for April 2024. As a result, the reported expenditures are greater than the obligations. Agriculture is working to identify the error and correct these amounts for future reporting.

dSeveral provisions in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 authorized increases in Medicaid payments to states and U.S. territories. At the time of enactment, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that federal expenditures from these provisions would total approximately $76.9 billion through fiscal year 2030. The largest increase to federal Medicaid spending is based on a temporary formula change rather than a specific appropriated amount. Some of the estimated costs in this total are for the Children’s Health Insurance Program, permanent changes to Medicaid, and changes not specifically related to COVID-19. This increased spending is not accounted for in the funding provided by the COVID-19 relief laws and is therefore not included in this table.

eAmounts shown in columns may not sum to the totals because of rounding.

As of April 30, 2024, $52.4 billion or 1 percent of the total amount of funding provided for COVID-19 relief remained available for obligation (unexpired unobligated balance). Additionally, $40.1 billion was expired (expired unobligated balance), meaning that this amount was not available for incurring new obligations but was available for recording eligible obligation adjustments. Table 2 provides additional details on funding, obligations, unobligated balances, and expenditures of government-wide COVID-19 relief funding with the largest unexpired unobligated balances.

|

Spending areas (dollars in billions) |

COVID-19 relief funding |

Total obligations |

Total expenditures |

Expired unobligated balance |

Unexpired unobligated balance |

|

Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation Funda (Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation) |

77.8 |

53.9 |

53.9 |

0.0 |

23.8 |

|

U.S. Coronavirus Refundable Credits (Department of the Treasury) |

98.8 |

92.2 |

92.2 |

0.0 |

6.8 |

|

Public Health and Social Services Emergency Fund (Department of Health and Human Services) |

337.3 |

332.6 |

298.6 |

0.0 |

4.7 |

|

Disaster Relief Fundb (Federal Emergency Management Agency) |

94.4 |

93.9 |

83.4 |

0.0 |

4.1 |

|

Tenant-Based Rental Assistance (Department of Housing and Urban Development) |

6.2 |

3.6 |

3.3 |

0.0 |

2.7 |

|

Emergency Connectivity Fund for Educational Connections and Devices (Federal Communications Commission) |

7.2 |

6.0 |

4.5 |

0.0 |

1.7 |

|

State Small Business Credit Initiative (Department of the Treasury) |

9.7 |

8.8 |

2.8 |

0.0 |

0.9 |

|

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-Wide Activities and Program Support (Department of Health and Human Services) |

25.2 |

24.3 |

17.9 |

0.0 |

0.8 |

|

Other areas (includes over 250 accounts) |

3,993.3 |

3,953.2 |

3,852.4 |

40.0c |

6.9 |

|

Totald |

4,649.9 |

4,568.5 |

4,408.9 |

40.1 |

52.4 |

Source: GAO analysis of data from the Department of the Treasury and applicable agencies. | GAO‑24‑107175

Note: COVID-19 relief funding, obligation, and expenditure data shown for the major spending areas are based on data reported by applicable agencies to Treasury’s Governmentwide Treasury Account Symbol Adjusted Trial Balance System. Federal agencies use this system to provide proprietary financial reporting and budgetary execution information to Treasury. These amounts can fluctuate from month to month. COVID-19 relief funding is the cumulative amount of funding provided in the six COVID-19 relief laws that Treasury uses to record and track COVID-19 relief spending, in accordance with Office of Management and Budget guidance. Further, the $4.65 trillion total reflects rescissions of COVID-19 relief funding enacted in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, Pub. L. No. 118-5, 137 Stat. 10, 23-30, div. B, tit. I (2023), and other laws. The most recent date for which government-wide information was available at the time of GAO’s analysis was April 30, 2024.

aUnder section 9704 of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, classified at 29 U.S.C. 1305(i), 1432, the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation will receive the necessary funding from the General Fund of the U.S. Treasury through fiscal year 2030 to provide payments to qualifying multiemployer plans, as defined in this law, so that the plans can pay benefits at plan levels through the end of plan year 2051. The requested amount will fund the Special Financial Assistance payments to qualifying plans and the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation’s related administrative and operating expenses. Neither the plans nor the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation are required to repay amounts received under this American Rescue Plan Act of 2021-established program, which is funded by appropriations from the General Fund of the U.S. Treasury.

bFunding provided to the Disaster Relief Fund is generally not specific to individual disasters. Therefore, Treasury’s methodology for determining COVID-19-related obligations and expenditures does not capture obligations and expenditures for the COVID-19 response based on funding other than what was provided in the COVID-19 relief laws. Further, Treasury’s methodology includes all obligations and expenditures based on funding in the COVID-19 relief laws, including those for other disasters. In its Disaster Relief Fund Monthly Report dated May 7, 2024, the Department of Homeland Security reported COVID-19-related obligations totaling $127.4 billion and expenditures totaling $105.3 billion as of April 30, 2024.

cThe Department of Agriculture’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program comprised about $34.0 billion, or 85 percent, of the total expired unobligated balance as of April 30, 2024.

dAmounts shown in columns may not sum to the totals because of rounding.

Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic Can Help Federal Agencies Better Prepare for Emergencies

A government-wide approach was needed to respond to and recover from the unprecedented scope and scale of the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on a review of our COVID-19 oversight work, as well as our oversight work on other public health emergencies, we identified lessons learned that federal agencies could use to better prepare for, respond to, and recover from future public health emergencies. These lessons learned highlight areas where government agencies did well in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and areas where the government response could have been improved. We categorized these lessons into seven topic areas. See figure 3. Across these seven areas, federal agencies have opportunities to enhance the nation’s preparedness for future public health emergencies by taking steps to implement recommendations we made in our body of work on COVID-19 oversight.

Planning in Advance

|

|

Lessons Learned on Planning in Advance Advanced plans—including national-level strategies and department- and agency-level plans—provide vision for how the federal government will respond to public health emergencies and are critical to the nation’s preparedness and ability to implement a timely response. To further enhance their preparedness, federal agencies should · clearly define their roles and responsibilities and those of their response partners in response plans, and exercise these plans prior to emergencies; · understand their capabilities and limitations and those of their response partners, and reflect these capabilities and limitations in response plans; and · build their capacity and collect lessons to inform and update plans. We have found instances where federal agencies could improve their preparedness by taking such steps. For example, the Department of the Treasury has not incorporated lessons GAO identified from the COVID-19 assistance programs to the aviation industry into its efforts to compile resources to prepare for future financial disasters. Taking such steps could help Treasury facilitate timely decisions and avoid encountering past challenges when responding to future emergencies. Further, we have made recommendations to federal agencies to improve their emergency response plans. For example, we recommended that the Department of Health and Human Services develop plans outlining steps to mitigate shortages in needed medical supplies, develop a comprehensive testing strategy, and develop an approach for assessing and addressing known challenges and future risks associated with advanced development and manufacturing of medical countermeasures, including vaccines. |

Source: GAO (text); Kinder/stock.adobe.com (icons). | GAO‑24‑107175

National-level strategies. A whole-of-nation approach is needed to prepare for, respond to, and recover from significant public health emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. National-level strategies that are developed prior to an emergency can provide vision for and facilitate implementation of a timely response. Further, these strategies inform federal departments’ and agencies’ emergency response plans that guide their response activities. For example, the National Biodefense Strategy provides strategic vision for preparedness and response planning and outlines specific goals and objectives to help the nation prepare for and respond to nationally significant biological incidents.[22] The White House issued an update in October 2022 to the National Biodefense Strategy, which was originally issued in 2018. We have ongoing work to assess this updated strategy and actions to implement it. As part of this work, we will continue to monitor implementation efforts related to the updated strategy.

Our prior work has examined the 2018 National Biodefense Strategy. This strategy included two goals that specifically address preparedness and response actions needed to limit the effects of biological incidents. These goals were meant to inform key federal agencies’—such as HHS and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)—interagency response and crisis action plans for nationally significant biological incidents, such as response plans to pandemics. However, we have reported gaps in planning for and responding to nationally significant biological events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. These gaps have limited agencies’ ability to achieve preparedness and response goals outlined in the 2018 National Biodefense Strategy. For example:

· In February 2020, we found that early efforts to implement the strategy represented only the start of a process and a cultural shift that may take years to fully develop, and agencies faced challenges that they must overcome to ensure success in the long term.[23] For example, individual agencies faced a lack of planning and guidance to support the implementation of an enterprise-wide approach to biodefense.[24]

We recommended that HHS take steps to ensure that challenges experienced early during the strategy’s implementation are adequately addressed. As of February 2024, HHS communicated it had taken some steps in collaboration with other federal agencies and departments to address our recommendation; however, HHS no longer has the authority to implement it. According to the updated 2022 National Biodefense Strategy, the White House now leads efforts to implement the strategy. Our ongoing work will continue to monitor implementation efforts related to the updated strategy.

· In August 2021, we identified gaps in the nation’s biodefense enterprise, which limited the federal government’s ability to implement the preparedness and response goals of the National Biodefense Strategy. We recommended that DHS, the Department of Defense (DOD), HHS, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) take steps to define a set of capabilities that account for the unique elements specific to responding to nationally significant biological incidents.[25] As of March 2023, these departments had been working with partners to comprehensively review the federal government’s bio-preparedness policies and plans. According to the updated 2022 National Biodefense Strategy, the White House now leads efforts to implement the strategy. Our ongoing work will continue to monitor efforts to implement the updated strategy.

Department- and agency-level response plans. Department- and agency-level response plans that are developed before emergencies occur and are aligned with national strategies can further guide federal efforts when responding to public health emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Without such plans, federal and response partners’ actions can be piecemeal and can cause confusion. For example, we found that a comprehensive national plan could help the U.S. aviation system streamline its response to emergencies.[26] We had previously reported that both the federal government and the aviation industry took actions early in the pandemic intended to limit the spread of COVID-19 through air travel. We stated at the time that, while these actions were helpful, some aviation stakeholders highlighted their piecemeal nature, which may have contributed to confusion early in the pandemic.[27]

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, we urged Congress to require the Department of Transportation (DOT) to develop a national aviation preparedness plan for communicable disease outbreaks. We had previously recommended in 2015 that DOT develop such a plan, but the recommendation remained unaddressed.[28] In June 2020, we emphasized that the absence of a national plan undermined the ability of the public health and aviation sectors to coordinate a response or provide consistent guidance to airports and airlines. We also noted the plan could serve as the basis for testing communication mechanisms among responders and ensure staff have received appropriate training to reduce exposure. Furthermore, we noted that the existence of a national plan might have reduced some of the confusion among aviation stakeholders and passengers early in the pandemic.[29]

In December 2022, legislation was enacted that required DOT to develop an aviation preparedness plan for communicable disease outbreaks.[30] In April 2024, officials within DOT’s Federal Aviation Administration told us that they are drafting such a plan. As part of this process, officials are coordinating internally within the administration; with other federal agencies, including DHS and HHS; and international stakeholders. Once that is complete, coordination will begin with other external stakeholders, including airlines, airports, and labor organizations, according to the Federal Aviation Administration. Officials anticipated finalizing the plan by the end of December 2024.

DOT officials told us previously that they have used lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as from the Ebola, SARS, and other communicable disease outbreaks, to inform the draft plan. Finalizing the forthcoming plan, including incorporating lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, will better position DOT and other aviation stakeholders to address a communicable disease threat while minimizing unnecessary aviation disruptions.

In addition to creating response plans, federal agencies should have a coordinated, department-wide approach to identify and resolve challenges encountered while implementing response plans during past emergencies. Without such an approach, agencies are susceptible to repeating past mistakes. For example, in April 2024 we reported that only three of the six HHS component agencies that are involved in public health emergency responses—the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR), CDC, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—carry out their own after-action programs to identify challenges from past public health emergencies.[31]

Further, we reported that coordination among the existing after-action programs and with other component agencies was rare. Without creating a department-wide after-action program, HHS is missing an opportunity to improve its preparedness. To strengthen HHS’s ability to respond to future emergencies, we recommended that HHS develop and implement a department-wide after-action program that encourages collaboration across HHS component agencies and includes relevant external stakeholders.[32] HHS concurred with our recommendations. Further, HHS stated it is taking steps to address our recommendations by designating ASPR as the lead to ensure swift identification and resolution of lessons learned from public health emergencies through a centralized after-action review process that will include relevant stakeholders.

Agencies should take steps to further enhance their preparedness for future emergencies, including:

· clearly defining roles and responsibilities for all parties involved with implementing response plans and exercising those plans prior to emergencies,

· understanding their and their partners’ capabilities and limitations, and

· building capacity while also collecting lessons to inform and update plans.

Clearly defining roles and responsibilities. The scope and scale of the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the critical importance of clearly defining the roles and responsibilities for the wide range of federal agencies and other key partners involved when preparing for pandemics and addressing unforeseen emergencies. A lack of clear roles and responsibilities when preparing for an emergency has hampered the federal response in the past. We have reported that a lack of clear roles and responsibilities has been a recurring challenge in HHS’s efforts to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and other public health emergencies. For example:

· In April 2021, we reported that HHS did not clarify which HHS agency was in charge—including which HHS agency was responsible for managing infection prevention—when it helped repatriate U.S. citizens from abroad and quarantined them domestically at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic to prevent the spread of the virus. As a result, confusion ensued, and HHS put repatriates, its own personnel, and nearby communities at risk.[33]

· In April 2024, we reported similar concerns related to HHS’s initial response to the mpox outbreak, which was declared a public health emergency in the U.S. in August 2022.[34] The initial federal response was spread across multiple HHS agencies. Several state and local jurisdictions we interviewed said that HHS appeared to lack a central point of coordination in the beginning, potentially slowing the response. Additionally, in May 2024, we reported that there was confusion at state, local, and territorial levels regarding how to request and receive mpox supplies from the Strategic National Stockpile. This occurred because HHS agencies involved with the stockpile had not clearly defined roles and responsibilities, thereby complicating response efforts.[35]

We have recommended that HHS take steps to clarify agency roles and responsibilities to limit confusion and risks when responding to public health emergencies. For example, we recommended that HHS revise or develop new emergency repatriation response plans that clarify agency roles and responsibilities, including which agency would be responsible for evacuation and quarantine, during a pandemic.[36]

In response, HHS started a series of workgroup meetings with relevant stakeholders to develop a Federal Emergency Repatriation Operations Plan, among other documents. As of April 2024, HHS had drafted this plan and anticipated finalizing it in early summer 2024. To close this recommendation, HHS and its component agencies will have to demonstrate that they have agreed upon a plan that outlines agency roles and responsibilities, including those for an evacuation and quarantine, in the event of a pandemic.

We also recommended that HHS exercise repatriation response plans before a public health emergency to test the plans and update relevant plans based on lessons learned.[37] Regularly exercising preparedness plans with all response partners allows all involved parties to practice operationalizing the plans. Further, regularly exercising plans can help identify any gaps in procedures or barriers to plan implementation, including a lack of clarity around roles and responsibilities, so that they can be addressed before an actual event occurs.

In response to our recommendation, HHS has conducted two repatriation exercises. While these are positive steps, we have also previously stated that we are monitoring for HHS to conduct exercises with all relevant stakeholders, including other federal agencies, based on agreed upon repatriation plans in response to a pandemic. As noted above, HHS is working to finalize its Federal Emergency Repatriation Operations Plan, among other documents. To close this recommendation, HHS and its component agencies will need to conduct exercises with all relevant stakeholders based on agreed upon guidance that outlines agency roles and responsibilities in response to a pandemic.

Understanding agencies’ and response partners’ capabilities and limitations. It is important for federal agencies to understand their and their response partners’ capabilities and limitations, and that these capabilities and limitations are reflected in federal response plans. ASPR, the agency within HHS responsible for leading and coordinating all matters related to federal public health and medical preparedness, relies, in part, on partners to respond to emergencies. However, our prior work has shown that ASPR did not have a complete understanding of the capabilities and limitations of response partners, which created a vulnerability. For example, in September 2019 we reported that the agency did not have a full understanding of the capabilities and limitations of its support agencies, including DOD, DHS, and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), during the response to the catastrophic destruction in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico caused by Hurricanes Maria and Irma in 2017. Consequently, ASPR’s needs were not always aligned with the resources that its support agencies could provide, resulting in some deployed resources not being properly and efficiently utilized.[38]

We have also identified concerns with ASPR’s capabilities to fully execute its preparedness and emergency response activities, particularly as these responsibilities have increased. ASPR’s additional responsibilities include managing the Strategic National Stockpile and leading the medical product industrial base expansion effort to help establish a more resilient medical product supply chain for the nation. This was an area of concern during the COVID-19 pandemic and remains a concern.

Further, as we reported in January 2024, ASPR had not identified critical areas within it that needed workforce assessments or developed a plan to conduct them. It also had not conducted an agency-wide workforce assessment to prioritize the skills and competencies of greatest need to achieve the agency’s goals and mission.[39] Without conducting these assessments, ASPR cannot be assured that its workforce has the skills and competencies in place to perform its responsibilities and ultimately meet its mission of leading the nation’s response to public health emergencies.

To improve its capabilities to fully execute emergency response activities, we recommended that ASPR establish specific goals and performance measures to use for its new hiring office, identify the critical areas that need workforce assessments, develop plans to implement them, and conduct an agency-wide workforce assessment. HHS neither agreed nor disagreed with two of our recommendations and agreed with the other two recommendations. In its comments, HHS discussed plans to support workforce assessment efforts, among other steps to address our recommendations.

Building capacity and collecting lessons to inform plans. Building capacity, collecting lessons from prior emergencies, and using this information to inform response programs and plans can improve federal agencies’ preparedness for future public health and other emergencies.

For example, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) would be better prepared to quickly estimate resource needs to allow better management and planning by enhancing its modeling capacity. VHA requested supplemental funding to continue operations to meet its mission when the COVID-19 pandemic emerged in 2020 but was not prepared to estimate the amount of supplemental funding needed during such a catastrophic event.

In February 2024, we reported that the agency did not have the modeling capacity to enable it to prepare estimates of the supplemental funding it needed in the event of another pandemic or other catastrophic event. Specifically, VHA lacked modeling capacity, including data collection and the ability to run budget simulations on a continual basis, to systematically assess and manage the risk of catastrophic events.[40] We recommended that the VA Undersecretary for Health should enhance VA’s analytical modeling capacity to better enable VHA to prepare estimates of supplemental funding needed to address catastrophic events. VHA concurred with our recommendation and outlined actions to address it, including chartering a workgroup to evaluate appropriate models and estimate required resources needed in the event of specific catastrophic events, such as a pandemic.

Federal agencies can also better prepare for future emergencies by leveraging lessons learned and incorporating them into response programs and plans. For example:

· Federal agencies can leverage economic lessons from SBA’s Paycheck Protection Program to inform support programs for smaller businesses affected by emergencies. We previously reported that studies have shown that the Paycheck Protection Program increased employment in small businesses, generally improved their financial conditions, and likely strengthened local labor markets. However, we found that some portion of the program assistance did not initially go to areas hit hardest by the pandemic and that smaller businesses faced challenges obtaining program assistance, which may have limited the effect of the program.[41]

In response to such concerns, Congress and SBA made a series of changes that increased lending to businesses that faced challenges obtaining loans, such as targeting minority-owned businesses, in later phases of the program’s implementation. By considering relevant economic conditions and accounting for the unique needs of smaller businesses, agencies could better target relief programs to the hardest hit areas and improve accessibility to federal funds for smaller businesses during emergencies.

· Federal agencies can better prepare for future emergencies by collecting and sharing lessons learned from contracting in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, HHS and DHS, two of the top five agencies with the highest COVID-19 contract obligations as of August 31, 2020, did not include lessons learned as part of their COVID-19 response review even though they identified contracting challenges. Establishing mechanisms to formally collect and share lessons learned from stakeholders involved with contracting will help ensure agencies can apply lessons learned and positive processes in response plans for future emergencies.[42] DHS has since taken action to establish mechanisms to collect and share contracting lessons learned from future response efforts. As of April 2024, HHS has ongoing efforts to collect and share such lessons learned.

· HHS can be better prepared to meet the nations’ need for medical countermeasures during emergencies and when responding to threats of widespread illness posed by emerging infectious diseases, including new COVID-19 variants, by incorporating approaches to address known challenges in new plans and programs. Medical countermeasures are drugs, vaccines, and devices to diagnose, treat, prevent, or mitigate the health effects of exposure to chemical, radiological, nuclear, or biological agents, including viruses. Many factors make it difficult to rapidly develop and manufacture medical countermeasures in response to public health emergencies.

HHS created the Centers for Innovation and Advance Development and Manufacturing (CIADM) program in 2012 in response to challenges in developing countermeasures during prior emergencies. Under this program, HHS awarded funding to three contractors to establish sites to develop countermeasures. HHS used these sites to support the manufacturing of COVID-19 vaccines. However, program limitations, such as sites not receiving consistent funding and production work from HHS or external manufacturing partners, hindered the CIADM program’s effectiveness.

In 2022, HHS announced that it was ending the CIADM program and developing a new program model for rapid countermeasure production intended to replace it. We reported in February 2023 that HHS’s plans for this new program model were not fully developed, and it was unclear as to how the program model will address or mitigate known challenges and future risks. To avoid repeating the challenges of the CIADM program, we recommended that HHS incorporate into the development of its new program model an approach to systematically assess and respond to known challenges and future risks associated with advanced development and manufacturing of medical countermeasures. HHS concurred with our recommendation and stated it will work to ensure its new model program aligns with the principles outlined in our recommendation.[43]

· Treasury could be more prepared for future financial disasters by including lessons learned from COVID-19 financial assistance programs to the aviation industry as part of its efforts to compile resources, specifically policies and procedures from programs it has implemented. Treasury had to quickly design several COVID-19 financial assistance programs, including the $46 billion loan program for aviation and other eligible businesses under Section 4003 of the CARES Act. This effort was challenging as Treasury had to establish program infrastructure, develop credit standards, and draft loan documents in a short time frame and under difficult circumstances.

In December 2020, we reported that although Treasury’s policies and procedures for evaluating loan applications were generally consistent with internal controls, the program could have been improved.[44] In particular, at that time we reported that providing emergency financial assistance through multiple programs or multiple paths within a program may better accommodate businesses of varied types and sizes, and that Treasury should clearly communicate timelines for actions to align lender and borrower expectations, among other things. In addition, our prior work has shown that providing federal assistance to businesses facing emergency circumstances requires clear and consistent information be communicated to applicants and eligible entities.[45]

In May 2023, SIGPR reported on a $700 million loan that Treasury made through the loan program to Yellow Corporation, a trucking company formerly known as YRC Worldwide.[46] While Yellow Corporation was not a part of the aviation industry, the loan program was available to businesses critical to maintaining national security.[47] The SIGPR report found deficiencies in Treasury’s approach to reviewing, approving, and disbursing this loan. Recognizing the need to act quickly while also having policies and procedures in place before executing loans, SIGPR recommended that Treasury develop a contingency plan for financial disasters. Doing so would provide a framework for future direct lending programs and reduce implementation time and the possibility of errors and omissions.

In our prior work, we have emphasized that considering lessons learned can help Congress and Treasury provide financial assistance to businesses in a timely manner, while also ensuring adequate safeguards to minimize the risk to the federal government from a borrower not repaying the loan.[48] We have also identified collecting and sharing information and knowledge gained from positive and negative experiences as a key practice of a lessons learned process.[49]

In April 2024, Treasury officials told us they are compiling resources to prepare for future financial disasters and expect to complete this effort by the end of 2024. Specifically, officials are compiling policies and procedures from the COVID-19 financial assistance programs provided to the aviation industry and lending programs Treasury operated under the Troubled Asset Relief Program.[50] However, in doing so, they have not included lessons we and other auditing entities have identified for emergency financial assistance programs.

Treasury officials told us that they have not endeavored to create a specific plan for financial assistance programs for future crises because each scenario requiring emergency financial assistance is unique. Further, officials told us that Treasury does not have the resources to design plans that would respond to the varied contingencies that may arise. As such, Treasury officials said they are compiling resources that could be useful across sectors and goals for future financial assistance, such as liquidity of funds and employment retention. Including lessons we identified and those identified by other external entities could help Treasury create a broad framework for future financial assistance programs, by not only documenting past procedures but also noting general lessons from implementing the recent assistance programs for the aviation industry. This can help Treasury improve its future relief programs and avoid encountering some of the challenges it faced in the past. Given the need to act quickly in financial disasters, it would be beneficial for Treasury to include lessons learned in this effort to enable decisionmakers to make timely decisions in the future.

Key open recommendations. We have made recommendations to federal agencies to improve their emergency response planning. These included recommendations to HHS to develop plans outlining actions the federal government will take to help mitigate shortages in needed medical supplies; to develop a comprehensive testing strategy to allow for a more coordinated pandemic testing approach; and to systematically assess and respond to known challenges and future risks associated with advanced development and manufacturing of medical countermeasures, such as vaccines.

Agencies across the federal government have taken steps to address some of our recommendations to improve their preparedness for public health emergencies. However, agencies should take additional steps to strengthen their ability to prepare for, respond to, and recover from public health emergencies, including:

· HHS should develop and implement a coordinated, department-wide after‑action program that encourages collaboration among HHS’s component agencies and includes relevant stakeholders involved in each public health response.

· HHS’s ASPR should establish specific goals and performance measures to use for its new hiring office, identify the critical areas that need workforce assessments, develop plans to implement them, and conduct an agency-wide workforce assessment.

· HHS should update emergency repatriation response plans that clarify agency roles and responsibilities, including those for an evacuation and quarantine, during a pandemic. Further, HHS should conduct regular exercises with relevant stakeholders to test plans in response to a pandemic and update them based on lessons learned.

Collaborating with Response Partners

|

|

Lessons Learned on Collaborating with Response Partners Collaborating with response partners—including federal and nonfederal partners—before and during public health emergencies can help agencies efficiently implement response activities and continue operations. To help facilitate this collaboration, federal agencies should · identify partners key to implementing the response and regularly coordinate with them throughout the response, and · ensure their response partners understand their respective roles and related responsibilities in implementing the response. We have made recommendations to federal agencies to improve their coordination with response partners before and during public health emergencies. For example, we recommended that the Department of Health and Human Services share its plans to mitigate shortages in medical supplies with response partners and maintain up-to-date guidance for partners on requesting and receiving assets from the Strategic National Stockpile. |

Source: GAO (text); Kinder/stock.adobe.com (icons). | GAO‑24‑107175

Identifying and coordinating with partners. Federal agencies can enhance the response to a public health emergency by identifying relevant federal and nonfederal partners and regularly coordinating with them. Public health emergencies may result in wide-ranging challenges that no single agency can address. This requires federal agencies to collaborate with one another and with other partners—such as Tribes, states, U.S. territories, localities, and the private sector—to implement response activities. Our work has highlighted instances during the COVID-19 pandemic where federal agencies and private entities successfully collaborated to achieve response goals, including developing and administering vaccines. For example:

· In January 2022, we reported that collaboration between federal agencies and private sector partners enhanced activities to quickly develop and manufacture COVID-19 vaccines for the public.[51] To help make safe and effective vaccines available as quickly as possible, the federal government announced the creation of a partnership between HHS and DOD in April 2020, which began as Operation Warp Speed and later became the HHS-DOD COVID-19 Countermeasures Acceleration Group. HHS and DOD then made awards to vaccine companies and others to help them make vaccines available.

We found that by making awards to multiple vaccine companies, the agencies mitigated risks to meeting their vaccine goals. For instance, working with multiple companies reduced the risk of failure due to safety, efficacy, or manufacturing issues. We also found that the coordination between agencies and vaccine companies helped alleviate supply chain issues. For instance, HHS and DOD utilized the Defense Production Act to support manufacturing efforts by providing priority access to necessary materials.[52]

· In July 2021, we reported CDC’s coordination with the private sector played a critical role in administering COVID-19 vaccines in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities. CDC established the Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program, an agreement with pharmacy partners to conduct COVID-19 vaccination clinics for residents and staff of long-term care facilities, including nursing homes, in October 2020. As part of the program, vaccines were provided at no cost to residents, staff, and the facilities.

Additionally, the pharmacy partners—including CVS, Walgreens, and Managed Health Care Associates Inc.—managed the entire vaccination process at certain facilities. This included storing, handling, and transporting vaccines; administering vaccines; and fulfilling reporting requirements. We reported in March 2021 that many of the vaccinations in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities were administered through these partnerships.[53] Between December 2020 and May 2021, the partnership program administered more than 8.3 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines, according to CDC.[54]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we found instances where federal agencies did not regularly coordinate with response partners, and important opportunities to enhance response outcomes were missed. For example:

· In September 2020, we found that the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) could enhance its efforts to distribute COVID-19 supplies—including personal protective equipment, ventilators, and COVID-19 testing supplies—by coordinating with its response partners.[55] During the pandemic, FEMA was responsible for distributing these supplies to its response partners, including tribal, state, local, and territorial governments.

To help it make decisions on how supplies would be allocated throughout the pandemic, FEMA reviewed supply requests submitted by its partners. However, we reported that FEMA’s response partners faced challenges tracking the agency’s fulfillment of supply requests, which made it difficult for them to then determine what additional supply requests they needed to make. For example, an official from one state told us that they were not told when supplies would arrive, and shipments would “just show up” without advance notice. Another state official said that the FEMA regional office did not always specify where the supplies went or to whom they were delivered.

We recommended that FEMA work with its partners on solutions to help states enhance their ability to track the status of supply requests and plan for supply needs for the remainder of the pandemic response. Although the agency disagreed with our recommendation, it took several actions that addressed it. For instance, in 2022, FEMA released an updated distribution management plan guide that, according to FEMA, provided actionable guidance for tribal, state, local, and territorial agencies to effectively and efficiently distribute critical resources in the community.

· In May 2024, we reported that additional coordination with Tribes would help the federal government better prepare for future emergencies that may require Strategic National Stockpile assets.[56] HHS documentation and our interviews with selected Tribes and tribal organizations revealed various concerns Tribes had with requesting and receiving stockpile assets during recent emergencies, including the COVID-19 pandemic and the mpox public health emergency. These concerns included Tribes’ issues with receiving assets due, in part, to infrastructure or geography. For example, officials from one Tribe as well as a former official from another Tribe reported challenges with having the equipment and infrastructure needed to receive and store delivered assets.

While ASPR has made progress in defining pathways for how Tribes can request Strategic National Stockpile assets, it has not assessed how it will address unique tribal challenges related to receiving assets. Engaging with Tribes to assess these issues could help HHS and Tribes be better equipped to deliver and receive assets respectively, and they can collectively strengthen preparedness and response efforts for future incidents. We recommended that ASPR formally designate an entity to regularly engage with Tribes and relevant stakeholders to (1) assess the unique challenges, such as infrastructure and geography, that could affect the delivery of assets in the Strategic National Stockpile to Tribes during future emergencies and (2) develop options for how to address those challenges. The agency agreed with our recommendation.

Coordination between federal and nonfederal partners could also help federal agencies address challenges adopting vaccine development technologies and approaches that may enhance the nation’s ability to respond to infectious diseases. While vaccinations are a key part of individual and community health, vaccine development is complex and costly. In November 2021, we reported that innovative technologies and approaches may enhance the nation’s ability to respond to infectious diseases. For example, reverse vaccinology using computer-based analytics to assess a pathogen’s genetic information to accelerate the understanding of pathogens and their antigens—combined with existing research—helped researchers develop some COVID-19 vaccines more quickly and effectively.

However, key challenges may hinder the adoption of these innovative technologies and approaches. We identified nine policy options for policymakers, including federal agencies, to help address these challenges and economic challenges. For example, policymakers have opportunities to improve preparedness by supporting public-private partnerships that would help identify and respond to disease pathogens with pandemic potential.[57]

Communicating roles and responsibilities to response partners. To effectively coordinate with response partners during a public health emergency, federal agencies should ensure that response partners understand their respective roles and related responsibilities in implementing the response. Federal agencies should ideally define the roles and responsibilities of their partners in response plans and communicate these prior to an emergency. When roles are not established in advance of an emergency, federal agencies should do this early in the response. Our work during the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that when the roles and responsibilities of response partners are not clearly defined and communicated, agencies cannot be assured that their partners take timely actions needed to implement response activities. For example:

· In April 2021, we found that DOD’s depot management did not consistently take actions to ensure continued operations during the COVID-19 pandemic because depot personnel lacked clear guidance from DOD on their roles and responsibilities.[58] Long-term disruptive events like pandemics can diminish military readiness if personnel who repair and maintain complex weapon systems and equipment at DOD’s depots are physically away from the workplace for weeks or months.[59]

DOD issued a memorandum on March 20, 2020, notifying the Defense Industrial Base, which includes DOD depots, that they were identified as a critical infrastructure sector and had a special responsibility to maintain their normal work schedule.[60] However, DOD had not developed guidance or a communication plan to ensure that depot management and personnel were aware of their mission-essential status and the need to support readiness. Further, we reported that the roles and responsibilities of depot personnel as mission-essential personnel were not always clear to depot leadership and personnel. As a result, depot management improvised their operation plans, causing some depots to pause or reduce operations, and others to shift schedules rather than maintaining normal work schedules.

We made two recommendations that DOD take steps to ensure that its depot management and personnel are made aware of their mission-essential status and the need to support readiness during a long-term crisis affecting the depot workforce. DOD concurred with our recommendations and addressed them through various actions, such as establishing a website to communicate guidance to DOD personnel, including depot staff, and publishing a plan detailing the steps it will take to communicate mission-essential status during a pandemic.[61]

· In May 2024, we reported that ASPR could enhance the response to public health emergencies by addressing challenges jurisdictions identified regarding coordination with the federal government around Strategic National Stockpile assets during the COVID-19 pandemic and the mpox public health emergency.[62] We found that jurisdictions lacked up-to-date information from federal agencies on their roles and current processes for requesting and receiving stockpile assets, resulting in confusion among jurisdictions during recent public health emergency responses.

Specifically, there is no formal documented agreement between ASPR and CDC that details each agency’s roles and responsibilities related to stockpile operations, according to Strategic National Stockpile officials. Further, we found ASPR lacked standard operating procedures for updating key guidance based on the most current information. For example, the main guidance for requesting and managing stockpile assets was last updated in 2014.

We recommended that ASPR should work with CDC to clearly define its and CDC’s roles and responsibilities related to the Strategic National Stockpile in a formal document and share that document with jurisdictions. Additionally, we recommended that ASPR develop standard operating procedures outlining how and when guidance documents, such as those for requesting and receiving Strategic National Stockpile assets, are updated. If ASPR develops these standard operating procedures, jurisdictions will be more likely to have access to updated guidance that reflects current processes and, in turn, improve response efforts.

Key open recommendations. We have made recommendations to federal agencies to improve their coordination with response partners before and during public health emergencies. These included recommendations for HHS to provide response partners with the agency’s plans to mitigate shortages in needed medical supplies, and to ensure it maintains up-to-date guidance for response partners on the processes for requesting and receiving vaccines and other assets from the Strategic National Stockpile.

Agencies across the federal government have taken steps to address some of our recommendations to enhance collaboration between federal and nonfederal partners. Yet, agencies could further improve their ability to efficiently implement response activities by taking additional actions to address other recommendations that remain open, including:

· ASPR should develop standard operating procedures outlining how and when guidance documents, including guidance on requesting and receiving assets from the Strategic National Stockpile, are updated. ASPR should also formally designate an entity to regularly engage with Tribes and relevant stakeholders to assess the unique challenges that could affect the delivery of assets from the Strategic National Stockpile to Tribes during future emergencies and to develop options for how to address those challenges.

· SBA should—in coordination with FEMA and the Department of Housing and Urban Development and with input from key recovery partners—develop and implement an interagency plan to help ensure the availability and use of quality information to support federal agencies involved in disaster recovery in identifying access barriers or disparate outcomes.

Providing Clear and Timely Communications

|

|