RAILWAY-HIGHWAY CROSSINGS

Improvements Needed to Federal Technical Assistance About Pedestrian Projects Related to Trespassing

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Elizabeth Repko at repkoe@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107115, a report to congressional committees

Improvements Needed to Federal Technical Assistance About Pedestrian Projects Related to Trespassing

Why GAO Did This Study

In 2023, there were nearly 1,900 crashes at railway-highway grade crossings—where railroad tracks and roads or pedestrian walkways intersect at the same level. These crashes have increasingly involved pedestrians. FHWA administers RHCP to improve safety at crossings nationwide, providing at least $245 million per year to states. IIJA introduced several changes to the program, which helped expand funding flexibility and clarify funding eligibility.

IIJA includes a provision for GAO to review RHCP. This report examines (1) how states used program funding and what a subset of states reported about crossing improvements, (2) stakeholders’ perspectives on program changes made by IIJA and how changes may affect safety improvements for crossings, and (3) FHWA’s technical assistance to states.

GAO reviewed relevant statutes and regulations and analyzed program data and crash data submitted by a subset of states. GAO interviewed FHWA and state officials, local entities, and railroads from six states—selected for program funding amounts received, among other factors. State and local perspectives are not generalizable. GAO assessed FHWA’s technical assistance against federal internal control standards.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is recommending that FHWA provide additional information about the types of pedestrian projects related to trespassing that might be eligible for RHCP funding. The Department of Transportation concurred with GAO’s recommendation.

What GAO Found

The Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) provides funding for states to improve safety at public crossings through the Railway-Highway Crossings Program (RHCP). GAO found that states used RHCP funding to address safety risks. For example, states added or upgraded existing equipment at crossings—such as bells, lights, and gates—from 2019 through 2023. During the same period, states reported that 77 percent of projects had zero crashes at the crossing before and after using program funding. State officials told GAO that RHCP projects help address the overall safety risks at crossings.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) introduced several changes to the program in 2021. For example, the act increased the federal cost share from 90 percent to 100 percent and expressly made pedestrian projects related to trespassing eligible for program funding. Stakeholders from six states GAO spoke with said these program changes expanded funding options and clarified funding eligibility. However, state officials said it is too soon to fully assess any safety effects from the program changes.

FHWA provides technical assistance to help states improve crossing safety, but GAO found that FHWA’s technical assistance does not describe or provide examples of the types of pedestrian projects related to trespassing that may be eligible for RHCP funding. Department of Transportation officials told GAO that trespassing at grade crossings is a significant concern because pedestrian fatalities and injuries at grade crossings are increasing. FHWA officials told GAO a pedestrian project is one that provides safety for pedestrians, including those who are trespassing, but GAO found that FHWA’s technical assistance was not clear about the types of pedestrian projects related to trespassing that are eligible for RHCP funds. Providing additional information about such projects would better position states to reduce pedestrian fatalities and injuries at grade crossings.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Abbreviations

|

FHWA |

Federal Highway Administration |

|

FRA |

Federal Railroad Administration |

|

IIJA |

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

|

LED |

light-emitting diode |

|

RHCP |

Railway-Highway Crossings Program |

April 10, 2025

The Honorable Shelley M. Capito

Chairman

The Honorable Sheldon Whitehouse

Ranking Member

Committee on Environment and Public Works

United States Senate

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

Crashes involving trains, vehicles, or pedestrians at railway-highway grade crossings—where roads and railroad tracks intersect at the same level—are one of the leading causes of railroad-related fatalities and injuries. In 2023, there were nearly 1,900 accidents at public crossings and over 800 fatalities and injuries.[1] The U.S. railroad system consists of a vast network of more than 600 railroads operating across 140,000 route miles of track, including approximately 204,000 grade crossings, of which about 130,000 are public crossings.

The Railway-Highway Crossings Program (RHCP), administered by the Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), provides funding for states to eliminate hazards and implement safety improvements at public railway-highway crossings, among other purposes.[2] States can use this funding to install new protective devices, such as flashing warning lights, and to replace existing devices that are functionally obsolete. The RHCP was most recently amended by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) in 2021 which, in part, granted states more discretion for using RHCP funding. It also expressly made two types of projects eligible for RHCP funding.[3] In addition, for fiscal years 2022 through 2026, FHWA is required by statute to set aside at least $245 million annually for RHCP.[4]

The IIJA includes a provision for us to review the RHCP.[5] This report examines (1) projects that states have funded with RHCP and what a subset of states reported about grade crossing improvements, (2) stakeholders’ perspectives on RHCP changes made by IIJA and how these changes may affect state safety improvements for grade crossings, and (3) technical assistance FHWA provides to states improving grade crossing safety and how FHWA could strengthen this assistance.

To describe projects states funded with RHCP and what a subset of states reported about grade crossing improvements, we analyzed data for RHCP projects as reported annually by the 50 states and the District of Columbia to FHWA from 2019 through 2023. We also reviewed data submitted by a subset of states to evaluate previously completed projects, including the number of crashes at each crossing before and after a project’s completion. We interviewed FHWA officials, as well as state officials and rail stakeholders from six selected states, to understand what project improvements were funded by RHCP. We also selected a nongeneralizable sample of six states for an in-depth review—Alabama, Delaware, Florida, Indiana, Texas, and Washington—based on several factors, including the level of RHCP funding received and the average number of grade crossing accidents in the state. We reviewed additional documents, such as a selection of states’ grade crossing action plans, to understand how states identified high-risk grade crossings, prioritized necessary improvements, and measured project effects.[6] We also reviewed applicable statutes, regulations, and FHWA guidance on RHCP, and other documents. To understand grade crossing safety and trends, we analyzed Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) data on nationwide grade crossing accidents, including fatalities and injuries, from calendar year 2014 through calendar year 2023.[7] We determined that RHCP project data and FRA accident data were sufficiently reliable for our purposes.

To describe stakeholders’ perspectives on RHCP changes and how these changes may affect state safety improvements for grade crossings, we reviewed RHCP changes made under IIJA. We selected five of the changes made under IIJA, including increasing the federal share of eligible project costs from 90 percent to 100 percent. We interviewed the state departments of transportation and 15 local entities and railroads from the six selected states about any effects selected program changes made under IIJA may have on their project selections. State and local perspectives are not generalizable. We interviewed FHWA and FRA officials, as well as state officials and rail stakeholders from the six selected states, to understand how these changes may affect state grade crossing safety improvements.

To identify the technical assistance FHWA provided to states for improving grade crossing safety and how FHWA could strengthen this assistance, we reviewed relevant guidance, webinars, and other information on the agency’s website. We also reviewed FRA’s railway-highway grade crossing safety and trespass prevention information and other relevant technical resources available on its website. We assessed the different types of FHWA technical assistance and how the information directly addressed the five RHCP changes made under IIJA that we selected. We also determined whether the technical assistance provided clarification to help states better implement RHCP or identify RHCP projects. We compared FHWA’s technical assistance with Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government—specifically, the principle for communicating the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[8]

We also interviewed officials from FHWA headquarters and selected division offices, FRA, selected states and localities, and railroads to understand how states used FHWA’s technical assistance on RHCP, how FHWA updated it when RHCP changes occurred, how users perceived its usefulness, and if there were any reported or known gaps. For further information on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Roles and Responsibilities for Rail Safety

In distributing RHCP funding each fiscal year among states, FHWA uses a statutory formula that includes factors such as federal-aid highway mileage and the number of public railway-highway crossings in each state.[9] FHWA issues program guidance, monitors states’ use of RHCP funds, reviews annual reports states are required to submit, and provides technical assistance. States are required to identify RHCP projects through data-driven methods, including consideration of the relative risks of grade crossings within their state based on factors such as accident rates and severity.[10]

FRA oversees railroad safety, including by regulating grade crossing safety and collecting nationwide data on grade crossing accidents.[11] Further, FRA works with FHWA to issue guidance and provides technical assistance aimed at improving safety at crossings nationwide. FRA also awards discretionary grants to states, local governments, and other eligible entities for rail planning, infrastructure, and safety projects. While not all these grants are solely for the purpose of funding safety projects for grade crossings, they may fund such projects.[12]

Each state ensures grade crossing safety within its jurisdiction. States prioritize and select projects for RHCP funding, in part, by assessing the safety risks posed at grade crossings and determining improvements needed to increase safety. We previously reported that states consider a variety of factors when identifying risk at crossings, such as output from accident prediction models.[13] Further, there are safety risks at crossings associated with trespassing. Legal definitions of trespassing specifically on railroad property differ across states. Some states do not have specific laws governing trespassing on railroad property but have more general property trespass laws that may be applicable to railroad property.

Railroads also ensure grade crossing safety. Specifically, railroads maintain crossing infrastructure, such as tracks and warning devices, to ensure safe operation at grade crossings. They also collaborate with federal, state, and local agencies, reporting accidents and coordinating crossing upgrades, closures, and safety improvements to help improve overall crossing safety in communities. According to the Highway-Rail Crossing Handbook, because railroads control access to their property, including grade crossings, and frequently construct or contract to construct RHCP projects, their participation with states and localities is essential.[14]

Railway-Highway Crossings Program

For fiscal years 2022 through 2026, FHWA is required by statute to set aside at least $245 million annually for RHCP from the Highway Safety Improvement Program formula funding that it administers. FHWA then distributes RHCP funding among the states. For fiscal year 2025, FHWA distributed funds to states ranging from about $1.2 million to $21 million.[15] States use this funding to implement different types of safety improvements and address high-risk grade crossings. For example, states can install new protective devices, such as flashing warning lights, and replace existing devices that are obsolete. Safety improvements at grade crossings include, but are not limited to, using various warning and traffic control devices, similar to how intersecting roads generally have stop signs or traffic signals.

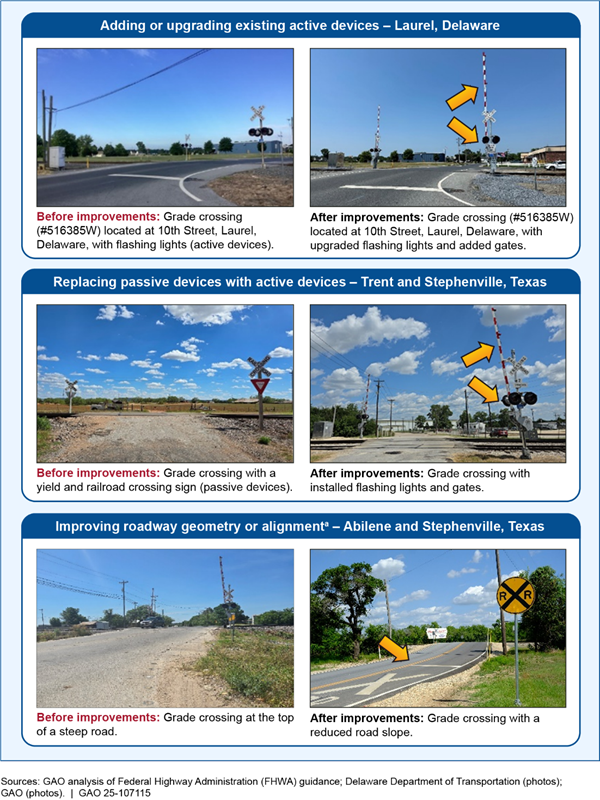

Grade crossings can be considered passive or active. At passive grade crossings, only signs or pavement markings indicate the presence of a crossing and possibly a train. In contrast, active crossings are equipped with a warning system, that can include bells, flashing lights, gates, or other devices activated by an approaching train, in addition to signs and pavement markings. FHWA reported in the RHCP 2022 Biennial Report to Congress that, of the 130,209 public railway-highway crossings in the U.S., 54 percent were active crossings, and 46 percent were passive.[16] See figure 1 for examples of RHCP project types.

Figure 1: Examples of Railway-Highway Crossings Program Project Types, Before and After Improvements

Note: The images in each row are examples of the same type of grade crossing improvement project. The images labeled “before improvements” show planned Railway-Highway Crossings Program (RHCP) projects, and the images labeled “after improvements” show completed RHCP projects. The images in the middle and bottom rows were taken at different locations.

aProjects that improve roadway geometry adjust the road slope or length leading to a grade crossing. Projects that improve alignment change the angle where the road and railroad tracks intersect, making it easier for drivers to see in both directions.

The IIJA introduced several changes to RHCP, which include

1. increasing the federal share of eligible RHCP project costs from 90 to 100 percent;

2. increasing the maximum incentive payment that a state may pay a local government for crossing closures from $7,500 to $100,000;

3. removing the 50 percent funding set-aside requirement for the installation of protective devices;

4. expressly providing that the replacement of certain functionally obsolete equipment is an eligible project expense; and

5. expressly providing that projects to reduce fatalities and injuries of pedestrian trespassers at grade crossings are eligible for funding.

We previously recommended that the Department of Transportation evaluate whether states received sufficient flexibility to adequately address current and emerging grade crossing safety issues.[17] In response to our recommendation, the agency conducted a study and reported various state challenges, identified notable practices to improve RHCP implementation, and offered suggestions to enhance its flexibility and effectiveness.[18] According to FHWA officials, the IIJA made changes to RHCP, in part, due to this 2020 study.

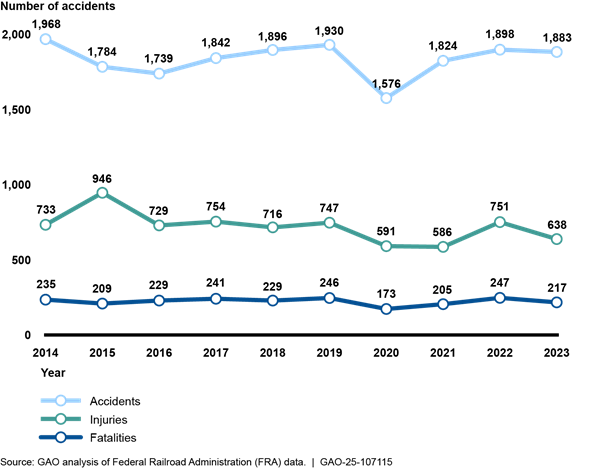

Trends in Crossing Safety

In 2018, we reported that since 2009, the number of crashes and fatalities at crossings had plateaued nationwide.[19] From calendar year 2014 through calendar year 2023, the number of accidents and fatalities has also remained relatively level, with a notable decrease in 2020, which coincided with decreased travel and economic activity due to the COVID-19 pandemic (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Number of Accidents, Fatalities, and Injuries at Public Railway-Highway Crossings Nationwide, Calendar Years 2014 Through 2023

Note: FRA accident/ incident data were downloaded on October 29, 2024, reflecting data as of August 31, 2024.

FRA regulations require that railroads report each accident at a railway-highway grade crossing to FRA regardless of the extent of damages or whether a fatality occurred.[20] According to Association of American Railroads representatives, nearly all crashes can be attributed to trespassers or driver behavior. Our analysis of FRA data shows that, from 2014 through 2023, about 88 percent of the accidents resulted from four primary causes, respectively: (1) failing to stop, (2) stopping on the crossing, (3) going around a gate, and (4) other related actions. For example, in 2023, drivers and pedestrians failing to stop was the leading cause of accidents at public grade crossings, accounting for 31 percent, or 584 of 1,882 total accidents. Stopping on the crossing was the next leading cause, contributing to 26 percent of the total accidents. The leading causes highlight that most accidents involve drivers and pedestrians failing to obey crossing warnings or stopping inappropriately on railroad crossing tracks.

According to a 2018 FRA report to Congress, between November 2013 and October 2017, 74 percent of all pedestrian trespasser fatalities (excluding suicides) occurred within 1,000 feet—less than one-quarter mile—of a grade crossing.[21] Accidents involving pedestrians on public grade crossings in the U.S. have been a continuing challenge. According to our analysis of FRA data, there were 183 accidents and 87 fatalities involving pedestrians on public grade crossings in 2023.[22] This represents a 20 percent increase in accidents and a 19 percent increase in fatalities involving pedestrians since 2014.

States Largely Used RHCP Funding to Upgrade Safety Devices, and a Subset of States Reported Fewer Crashes at Improved Crossings

States Most Frequently Used RHCP Funding to Add or Upgrade Existing Warning Devices at Railway-Highway Crossings

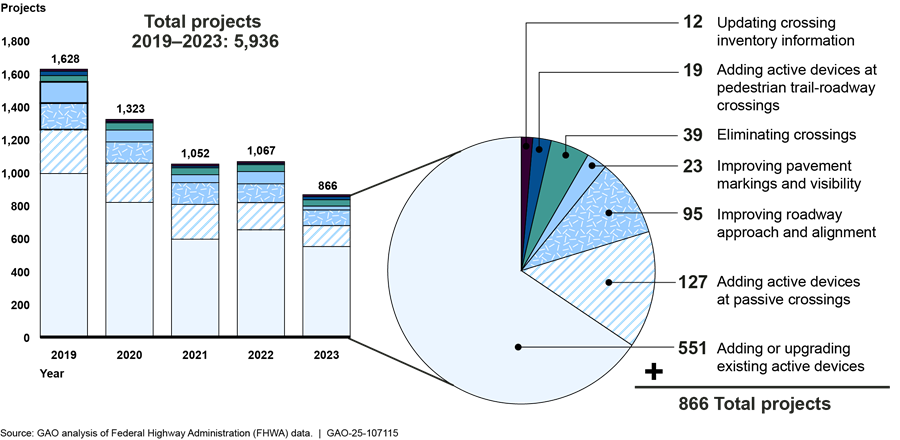

According to our analysis of RHCP projects from 2019 through 2023, states most frequently reported adding or upgrading bells, lights, and gates at crossings that already had these active warning devices. Specifically, of the approximately 6,050 projects reported by states between 2019 and 2023, about 3,600 added or upgraded existing active devices.

For states’ annual reports to FHWA, agency guidance notes that states should provide a list of all projects they funded using RHCP funds during the reporting period, among other information.[23] Our analysis identified seven categories of RHCP projects:

1. upgrading or adding additional active devices (bells, lights, gates, or other warning equipment activated by the presence of a train) to a crossing that already had them;

2. adding active devices at a passive crossing (a crossing with only signs or pavement markings);

3. eliminating a crossing by closing the crossing or building an overpass or underpass to separate the crossing;

4. improving the approaches to a crossing, such as adding medians or sidewalks, or improving the crossing’s alignment with the road;

5. improving pavement markings or crossing visibility;

6. adding active devices at walkway-railway crossings; and

7. updating the information in FRA’s railway-highway crossing inventory.

Figure 3 shows the number and type of RHCP projects reported annually by all states from 2019 through 2023. For example, in 2023, states reported funding 550 projects that added or upgraded active devices at a crossing with existing active devices, representing 64 percent of projects funded that year.[24]

Figure 3: Number of Railway-Highway Crossings Program Projects That States Annually Reported, by Project Type, 2019 Through 2023

Notes: The total counts exclude 128 records where states did not fill in the project types or crossing types in their reported data. Passive crossings include signs or pavement markings to denote the presence of a crossing. Active crossings have warning systems, which include signs and active devices, such as bells, flashing lights, or gates that are activated by the presence of a train.

Several state officials and stakeholders we interviewed said they focused on using RHCP funding at crossings with existing active devices because these crossings generally have higher safety risks. For example, Alabama officials said that they added gates to a crossing that previously only had flashing lights and upgraded control equipment to provide a constant warning time. The officials said this upgrade enhanced the crossing’s reliability and safety. Further, projects to upgrade active crossings may include pedestrian safety improvements or other types of crossing improvements. For example, Florida officials told us they plan to add a pedestrian crossing gate to the sidewalk near a road as part of a larger project upgrading the highway crossing’s active devices (see fig. 4).

According to state officials we met with, in general, projects’ upgrading active devices can vary in scope, complexity, and cost. State officials told us that some projects replace incandescent flashing bulbs with light-emitting diode (LED) lights, and others update crossing electronics, bells, lights, and gates with newer models. Some other projects add additional devices, acquire property, or address complex engineering, such as connecting railroad sensors to road traffic signals. According to officials, the cost of installing active devices in our selected states varied widely. For example, railroad representatives said one project to upgrade existing lights and gates at a crossing in Alabama was estimated to cost $325,000; officials said that a planned project in Texas to upgrade devices at six crossings and upgrade the electronics linking the railroad sensors to road traffic signals may cost around $6 million. Figure 5 shows a project that used RHCP funds to add equipment to a crossing that already had active devices. See appendix II for more examples of RHCP projects in our selected states.

Figure 5: Example of a Railway-Highway Crossings Program Project That Upgraded Warning Devices at a Grade Crossing

Additionally, the total number of projects funded by all states decreased each year from 2019 through 2023. Specifically, across all 50 states, the approximate number of projects funded annually decreased from about 1,650 projects to about 900 projects. Of the six states we selected, officials from four states and five project stakeholders attributed this change to increased project costs and supply chain challenges. For example, a Florida official said that the cost of each project has increased by at least 25 percent. Four project stakeholders and officials from one state attributed increased costs to recent inflation and said that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in increased lead times for materials, which delayed projects.

For individual states, the number of projects funded each year from RHCP varied to a moderate degree. For example, Indiana reported funding 23 projects in 2019, 75 projects in 2022, and 30 projects in 2023. Officials from our six selected states attributed this variation to several factors, such as the increase in project costs and coordination with railroads and local stakeholders. For example, Washington officials said that legal disputes with two of the state’s railroads concerning maintenance fees for crossings led the state to fund two projects in 2023 compared with 44 in 2019. Additionally, officials from two states—Delaware and Indiana—said that they may fund a larger-than-normal number of projects in one year by using carryover funding from prior years.[25]

Analysis of State Reports Generally Showed Zero Crashes or a Decrease in Crashes at Grade Crossings with Completed Projects

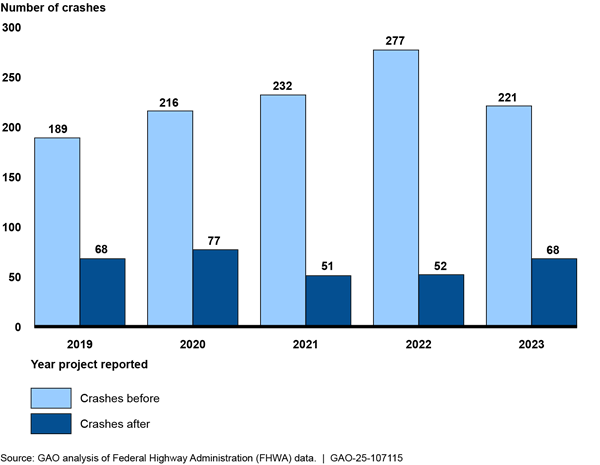

Most RHCP projects reported zero crashes at the crossing before and after project completion, according to our review of a subset of project accident data. States submit these data as a component of their required annual reports to FHWA (see text box). Specifically, our analysis found that approximately 2,400 of 3,100 completed projects from 2019 through 2023 (77 percent) had no crashes at the crossing both before and after project completion. State officials told us that RHCP projects addressed overall safety risks at crossings. As we have previously reported, state officials said it can be difficult to use before-and-after crash statistics as a measure of effectiveness because of the low number and often random nature of crashes.[26] Figure 6 shows the number of completed projects states reported each year, by change in crashes.

Figure 6: Number of Railway-Highway Crossings Program Projects, by Change in Crashes after a Completed Project Reported by a Subset of States, 2019 Through 2023

Note: The original dataset contained 6,518 records

submitted by all 50 states and the District of Columbia. These data represent a

subset of 3,085 records, including projects from 42 states with comparable

crash data periods from 2019 through 2023. There were 2,389 unique projects

reported across multiple years. The number of states included in the subset

each year varied from 30 to 36. We calculated before-and-after crash data by

summing all injuries crashes (which include crashes with fatalities and serious

injuries) and property damage only crashes reported by states and the District

of Columbia to FHWA in their annual reports.

|

States’ Crash Data Reporting Requirements for Grade Crossing Projects States submit reports to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) each year that contain, among other details, the number of crashes that occurred at crossings involved in projects. States collect data on the number of crashes at a crossing over several years. FHWA guidance says states should report at least 3 years of crash data before and after project completion. We reviewed project crash data submitted by a subset of states and found that states use different lengths of time to report these data. For our subset of data, we included projects from the three largest groups of project accident data: (1) projects with 5 years of preproject crash data and 5 years of postproject crash data, (2) projects with 3 years of preproject crash data and 3 years of postproject crash data, and (3) projects with 5 years of preproject crash data and 3 years of postproject crash data. Some states report the project to FHWA once they have collected sufficient years of postproject crash data, though some states submit data on a rolling basis. The actual completion of construction may vary. For example, our analysis of the subset of 2023 annual reports suggests that states included projects in the before-and-after comparison for that year that may have been completed between 2016 and 2023. See appendix I for more information on the variation of data collection methods, time periods reported by the states, and our subset selection. |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Highway Administration information. | GAO‑25‑107115

We also found that approximately 600 projects of the 3,100 projects in our subset (19 percent) observed a decrease in crashes after completing a project. We observed decreases in crashes across many types of projects, including improvements to pavement markings or visibility, adding or upgrading existing active devices, eliminating crossings, and improving roadway approach or alignment.

However, a small number of projects may contribute substantially to the overall reduction in crashes. For example, in 2023, Arkansas reported that a grade crossing in the city of Benton had 29 crashes before the start of a project to eliminate the crossing. The decrease from 29 to zero accidents after completion of the crossing elimination project represented about 19 percent of the total decrease in crashes for our subset of states that year. Figure 7 shows the number of crashes the 42 states included in our analysis reported before and after completing RHCP projects.

Figure 7: Number of Crashes Before and After the Completion of Railway-Highway Crossings Program Projects, Reported by a Subset of States, 2019 Through 2023

Note: The original dataset contained 6,518 records submitted by all 50 states and the District of Columbia. These data represent a subset of 3,085 records, including projects from 42 states with comparable crash data periods from 2019 through 2023. There were 2,389 unique projects reported across multiple years. The number of states included in the subset each year varied from 30 to 36. The data have a total of 1,135 crashes before the start of projects and a total of 316 crashes after the completion of projects. We calculated before-and-after crash data by summing all injuries crashes (which include crashes with fatalities and serious injuries) and property damage only crashes reported by states and the District of Columbia to FHWA in their annual reports.

Federal and state officials identified several factors that indicate an RHCP project’s effectiveness. Officials from FHWA and FRA told us they consider the project effective if it results in a reduction of at least one crash. Officials from most of our selected states generally said they use project-level crash data for evaluation, but some said they consider other factors in evaluation, such as whether there was an overall decrease in safety risk. For example, a Florida official proposed upgrades at one crossing due to the signal equipment being antiquated. If the equipment failed, it would be very hard (or even impossible) for the railroad to obtain the parts to repair the equipment. In cases like this, the official said it is best to be proactive rather than reactive. As we have previously reported, states said that not all projects occur at crossings where there has been a crash, and a project with no change, or an increase in crashes, does not necessarily mean the project was not successful at reducing the risk of a crash.[27]

Stakeholders Viewed RHCP Changes as Expanding Project Flexibility but Said It Is Too Early to Assess Safety Effects

Stakeholders from the six selected states we spoke with said that changes to RHCP introduced through the IIJA have provided states with expanded program funding flexibility and clarified project eligibility. According to FHWA, these changes were intended to address some challenges associated with the program, to clarify the eligibility of certain safety projects for RHCP funding, and to help with making grade crossing safety improvements. Selected state officials and other stakeholders we met with offered perspectives on how RHCP changes could affect state grade crossing safety improvements, as described in the following sections.

Increasing the federal share. The IIJA increased the federal share of eligible RHCP project costs from 90 to 100 percent.[28] Officials from five selected states said that increasing the federal cost share was a beneficial change because it allowed states to complete more crossing safety projects, among other reasons. Officials from four selected states also said that the previous RHCP requirement for states or localities to match 10 percent of project costs was a barrier, especially for smaller or financially constrained localities. Officials from three selected states told us the increased federal share will enable them to consider larger or more comprehensive safety upgrades. For example, Indiana officials said that the state used RHCP funding for 75 projects in 2022 that were previously backlogged because of difficulty securing matching funds.

Even with the increase in federal share, challenges persist with rising costs. Specifically, officials from five states said that increased costs—especially for materials and labor—have reduced the number of RHCP projects they can complete each year. Railroad representatives also said that significant cost increases for grade crossing safety projects are a nationwide issue. Specifically, they noted the cost to replace crossing gates doubled from about $400,000 to $800,000 or more over the last few years. They attributed this increase to factors like inflation and postpandemic supply chain issues, which drove up the price of materials and labor nationwide. Railroad representatives further said that states like Florida and Arizona started combining RHCP funds across multiple years as a strategic response to rising costs and to help pay for larger projects.

Increasing the maximum payment for closing crossings. States may make incentive payments to local governments when those governments permanently close public grade crossings under their jurisdictions but only if the railroad owning the tracks on which the crossing is located makes a payment to the local government with respect to the closure. The IIJA increased the maximum amount of RHCP funding that states may pay local governments from $7,500 to $100,000.[29] However, the incentive payment may not exceed the amount paid to the local government by the railroad. Officials from five selected states said the increase could encourage states to close railway-highway crossings, and state officials from the remaining selected state said the change would not have an effect on closures. Officials from one selected state said this increased payment can help the state close crossings by facilitating negotiations with smaller, rural communities.

Officials from all six selected states said they had not yet closed any crossings since this RHCP change was made. Even with the increase in the incentive payment to close crossings, officials from our five selected states said that challenges with closing crossings will remain because they continue to struggle to collaborate with railroads—which must make incentive payments to the government with respect to the closure before the state may make incentive payments to local governments.[30] State officials from four selected states also said that closing a crossing often involves additional costs, such as building new infrastructure to accommodate rerouted traffic. For example, in Florida, one official said that railroads may continue to be reluctant to support projects that could disrupt their operations or require additional investments. Florida officials also said that closing a crossing to replace grade crossing traffic control devices or improve crossing surfaces often requires creating alternative routes and upgrading nearby roads to handle increased traffic, such as widening lanes; adding intersections; or enhancing safety features like signals, signs, and lighting.

In Texas, one local stakeholder said that community concerns and high project costs remain influential factors in the decision-making process, particularly when a crossing serves as a critical connector for local traffic and agricultural activities in farming communities. According to state, local, and railroad officials we met with in Texas, communities may resist crossing closures due to concerns about changes to traffic flow, restricted neighborhood access, or the potential effects on emergency response routes.

Removing the funding requirement for installing specific devices. The IIJA removed a requirement that at least half of RHCP funds made available each fiscal year be set aside for installing protective devices, such as gates and signals.[31] Officials from six selected states said this was a beneficial change—allowing more flexibility in how the state could use funding. However, officials from two states said that they had not yet seen the effects of this change, and officials in another state said the change would have no effect on how the state used RHCP funds because they planned to continue using their existing project planning processes.

According to FHWA officials, this change provides states with the flexibility to objectively prioritize safety projects beyond installing protective devices, allowing more targeted interventions based on state-specific safety priorities at crossings. For example, Florida officials said that this change will allow them to spend more funds on innovative devices at grade crossings that can address the increasing traffic demands. Similarly, Texas officials plan to use this flexibility to improve road surfaces by leveling a road’s profile to reduce “humped” crossings across the state, which officials identified as a safety risk due to reduced driver visibility and vehicles potentially becoming stuck on tracks. Figure 8 shows a humped grade crossing prioritized for RHCP safety improvements.

Figure 8: A Humped Grade Crossing in Trent, Texas, Prioritized for Railway-Highway Crossings Program Funded Safety Improvements

Expressly providing that replacing certain obsolete equipment is an eligible expense. The IIJA also expressly provided that replacing functionally obsolete warning devices is an eligible project expense under RHCP.[32] For railway-highway crossing equipment purchased with federal-aid funds, FHWA guidance indicates that functionally obsolete equipment refers to equipment that is no longer needed for the purposes for which it was purchased.[33]

|

What Is a Trespasser? According to the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), a trespasser refers to any person who enters or remains on a railroad right of way, equipment, or facility without permission or legal right. This includes areas designated for railroad operations where unauthorized access poses significant safety risks. Source: Federal Railroad Administration. | GAO 25 107115 |

Officials from five selected states said they already use RHCP funds to replace obsolete equipment and plan to continue doing so. Examples include upgrading incandescent lights to energy-efficient LED flashing lights, which improves visibility by being brighter, and more visible from greater distances and angles, and offers a longer service life. Alabama officials said that using this flexibility to upgrade signal systems and install advanced warning devices in Birmingham significantly improved safety and reduced crashes. However, one state official stated that under FHWA rules, only obsolete equipment is eligible for replacement, and both incandescent and LED lights are considered acceptable equipment for such replacements.

Expressly providing projects that reduce fatalities and injuries of pedestrian trespassers are eligible for funding. The IIJA expressly provided that states can use RHCP funding for projects reducing pedestrian fatalities and injuries from trespassing at grade crossings.[34] Officials from six selected states told us they welcomed this change because of the growing number of crashes involving pedestrians trespassing at grade crossings. Indiana officials, for example, plan to implement flashing lights, warning bells, and automatic gates that prevent pedestrians from crossing tracks when a train is nearby. Similarly, they said they plan to install physical barriers (i.e., posts or poles) to prevent pedestrians and vehicles from accessing unauthorized areas of the tracks.

Nevertheless, states may continue to experience challenges with preventing risky pedestrian and driver behavior at crossings. Specifically, our analysis of FRA data comparing the periods 2014 through 2018 and 2019 through 2023 shows an increase in accidents caused by drivers and pedestrians that did not stop or circumvented lowered gates at grade crossings. For example, Florida’s 2023 RHCP annual report highlighted that even with bells, lights, and gates at grade crossings, many crashes were caused by individuals bypassing or disregarding these safety measures. One selected state official told us that infrastructure upgrades and improvements must be paired with education and enforcement efforts to effectively address the persistent issue of not obeying safety warnings at crossings (see text box). According to FRA and FHWA officials, they will continue to work together to reduce pedestrian trespassing injuries and fatalities by implementing a national prevention strategy and pedestrian trespasser safety projects under RHCP. In addition, FRA and FHWA both partner with Operation Lifesaver, Inc., on national education campaigns related to rail crossing safety.[35]

|

Beyond Engineering Options, Selected Stakeholders Reported Taking Other Steps to Promote Safety at Grade Crossings The three "Es" of grade crossing safety—engineering, education, and enforcement—combine to enhance safety by improving infrastructure, raising public awareness, and enforcing traffic laws at crossings. RHCP funds can be used for the preliminary engineering aspect of grade crossing safety; however, the education and enforcement aspects are not eligible for this funding and must rely on other resources for support. State departments of transportation, railroads, and safety organizations, such as Operation Lifesaver, Inc., have actively promoted public awareness campaigns to educate drivers and pedestrians about the dangers of making risky decisions at crossings. For example, officials from Alabama and Florida said that ongoing education campaigns aimed at both adults and school-aged children have proven essential in promoting safe behavior near rail crossings. These campaigns often use media, school programs, and community outreach to highlight the consequences of risky behaviors, such as bypassing gates or failing to stop when warning lights are flashing. In addition to education, stakeholders encourage stricter enforcement of traffic laws at crossings. For example, the Indiana Department of Transportation and local law enforcement agencies have collaborated to increase patrols at high-risk crossings, issuing fines to drivers and pedestrians who disregard safety measures. These enforcement efforts, alongside targeted awareness campaigns, aim to deter risky or dangerous behaviors and reinforce the importance of obeying safety measures. |

Sources: GAO analysis of state departments of transportation; and Operation Lifesaver, Inc. information. | GAO‑25‑107115

State officials from our six selected states said they were optimistic about the RHCP changes designed to improve grade crossing safety but that it is too soon to fully assess the long-term effects. Because these RHCP changes are recent, FHWA and these state officials explained that it will take time to see the effects, particularly for large, complex projects that require extensive planning and coordination. For example, an RHCP project in Texas involved seven major crossings and took nearly 10 years of negotiations between the Texas Department of Transportation, Union Pacific Railroad, and the City of Abilene to reach the construction phase. According to state officials, these delays were caused by the complexity of aligning schedules, securing approvals, and coordinating contributions from multiple stakeholders, leaving high-risk crossings vulnerable for years, or even decades. FHWA officials said that they will continue to monitor and evaluate the progress of RHCP-funded projects through annual state report submissions.

FHWA Offers a Range of Technical Assistance to States, but It Does Not Fully Address Issues Related to Trespassing

FHWA Offers Guidance, Webinars, and Other Technical Assistance to States for Improving Grade Crossing Safety

FHWA provides a range of technical assistance to help states evaluate, select, and implement projects using RHCP funding. Specifically, FHWA’s website provides guidance on topics such as RHCP eligibility and program requirements.[36] For example, the Highway-Rail Crossing Handbook, jointly produced by FHWA and FRA, provides general information on railway-highway crossings, characteristics of the crossing environment and users, and physical and operational changes that can be made at crossings to enhance the safety and operation of both railway and highway traffic.[37] It also contains information about best practices, as well as grade crossing standards. According to the handbook, it does not establish standards but provides guidance about applying existing standards and recommended practices to develop safe and effective improvements for crossings.

In addition, since November 2021, FHWA updated information available to states about RHCP changes under IIJA. This included webinars with an overview of RHCP changes and how they apply to states, questions and answers about RHCP changes, fact sheets about IIJA, and guidance for annual reporting requirements. States can also seek assistance on RHCP project questions directly from FHWA division offices in each state and the District of Columbia. Officials from four states we met with said they had obtained project eligibility clarification assistance from the state’s FHWA division office.

FHWA also interacts directly with grade crossing stakeholders, such as railroads. For example, FHWA has led a grade crossing working group that has met periodically since at least 2017. According to FHWA officials, this working group is intended to improve coordination between states and railroads by offering expertise on relevant projects and initiatives and sharing noteworthy practices, lessons learned and challenges, among other things. Likewise, FHWA officials attended and presented at national conferences, such as an August 2024 national conference focused on railway-highway crossing safety. FHWA also provides technical assistance through training and outreach in partnership with the National Highway Institute and FRA.[38]

Officials from our six selected states told us they viewed FHWA’s technical assistance as generally beneficial. Officials said they received a range of assistance from FHWA, including obtaining eligibility information from division offices, using information from the agency’s website, reviewing research, and participating in webinars. These state officials also identified areas where FHWA could provide additional technical assistance, which we discuss later in this report.

FHWA’s Technical Assistance Has Not Fully Addressed Pedestrian Projects Related to Trespassing

Internal control standards for federal agencies provides that management should externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entities’ objectives.[39] Further, FHWA’s Strategic Plan, Fiscal Year 2022–2026 states that safety is FHWA’s top priority.[40] According to the plan, one way to make progress toward this priority is to design and build transportation infrastructure and systems to improve safety outcomes. However, we found that FHWA’s technical assistance does not fully clarify eligibility for pedestrian projects related to trespassing funded by RHCP.

As previously discussed, IIJA amended RHCP to expressly provide that states could use program funds for projects to reduce pedestrian fatalities and injuries from trespassing at public grade crossings. According to FHWA, pedestrian safety improvements at a crossing, which include trespasser prevention, remain eligible. This means not only the safety of pedestrian trespassers but also trespasser prevention.

However, FHWA’s technical assistance materials do not describe the types of pedestrian projects related to trespassing that may be eligible for RHCP funding. Specifically, the Highway-Rail Crossing Handbook states that injuries and fatalities—whether accidental or intentional, such as with suicides—associated with trespassing are beyond the scope of the guide and that readers should consult FRA and other resources in addressing this topic. Further, FHWA’s May 2022 questions and answers document addresses pedestrian trespassing, but it does not provide any additional information beyond the text of the amended statute and its associated regulations. Finally, an FHWA webinar held in July 2022 also repeated the IIJA text regarding improving pedestrian safety at public grade crossings, including trespassing, and conveyed the requirement that such projects must be at public railway-highway crossings or railway crossings of a pedestrian pathway.

In addition to limited documentation about the types of pedestrian projects related to trespassing that might be eligible for RHCP funding, we also found differences between how FHWA and our selected states characterize two types of projects: pedestrian projects and pedestrian projects related to trespassing. FHWA officials did not distinguish between the two types of projects and said a typical pedestrian project would be considered one that improves pedestrian safety at a public crossing, including pedestrians trespassing at a public crossing. FHWA officials said pedestrian projects, including those to keep trespassers safe, would be eligible for RHCP funds.

In contrast, officials from four of the six states we spoke with saw the two types of projects differently. They said pedestrian projects are generally intended to facilitate safe access for pedestrians to cross where they should, while pedestrian trespasser projects are intended to prohibit pedestrians from crossing where they should not. Officials from one of the states suggested that a typical pedestrian project would include installing gates and lights for protection, whereas pedestrian projects related to trespassing could include barriers like installing plants or fencing to an area people are using as a shortcut that bypass safer routes.

Given the different perspectives about pedestrian projects related to trespassing, officials from selected states we spoke with said FHWA’s technical assistance about the eligibility of pedestrian projects related to trespassing for RHCP funds could be improved. While FHWA officials told us that projects that include guiding pedestrians to a safe crossing at or near the grade crossing would be eligible for RHCP funds, it is not clear this type of example has been communicated to states. For example, as discussed above, FHWA’s technical assistance does not include specific examples of projects that would be eligible. Officials from five of the six states we spoke with said additional information about pedestrian projects related to trespassing, such as examples of these projects, would be useful. For example, one state official told us that having such examples would be used as a best practice and would be considered in both states’ program planning and project selection. An official in another state told us that having examples of pedestrian projects related to trespassing would raise the visibility of such projects with localities and others who want to use RHCP funds in that state and that such examples would be a resource for those agencies during the state call for RHCP projects.

FHWA’s technical assistance has not fully addressed the types of pedestrian projects related to trespassing that might be eligible for RHCP funding because FHWA has not regularly reviewed and updated technical assistance for RHCP outside of statutory programmatic changes. As discussed earlier, in the case of pedestrian projects related to trespassing, technical assistance information was made available, but it reiterated material in the statute and did not provide examples of the types of projects that might be eligible for RHCP funding. Further, FHWA officials told us they make eligibility decisions on a case-by-case basis for pedestrian projects related to trespassing because they generally need to know the context surrounding the project to determine eligibility.[41]

FHWA providing additional information within its technical assistance about these types of pedestrian projects, including noteworthy examples, could better position states to decide whether to propose projects to reduce pedestrian fatalities and injuries from trespassing at grade crossings using RHCP funds. Department of Transportation officials told us that trespassing at grade crossings is a significant concern because pedestrian fatalities and injuries at grade crossings are increasing. According to our analysis of FRA data, in 2023, 89 pedestrians were killed at public railway-highway grade crossings, about 41 percent of grade crossing fatalities. This is up from about 31 percent of all grade crossing fatalities in 2014.[42] Providing additional information addressing pedestrian projects related to trespassing at railway-highway grade crossings and the types of projects eligible for RHCP funding is one way to help FHWA achieve its goal of building transportation infrastructure that improves safety outcomes.

Conclusions

While the number of grade crossing accidents nationwide has largely plateaued, the number of accidents has not decreased substantially for several years, and the share of accidents at grade crossings involving pedestrians has increased. FHWA provides technical assistance to help states make informed decisions about using RHCP funding, but this assistance could be improved. By reviewing and updating the technical assistance it provides to program recipients, FHWA could better ensure this assistance is meeting the needs of stakeholders. Moreover, updating this technical assistance to include information about pedestrian projects related to trespassing would better position states to address rising pedestrian fatalities at grade crossings.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Administrator of FHWA should review RHCP technical assistance materials and update them to add information about the types of pedestrian projects related to trespassing that might be eligible for RHCP funding. This could include providing examples of noteworthy projects. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments

We provided a copy of this report to the Department of Transportation for review and comment. In written comments, reproduced in appendix III, the Department of Transportation concurred with our recommendation and provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Transportation, the Administrator of FHWA, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at repkoe@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Elizabeth Repko

Director, Physical Infrastructure Issues

This report examines (1) projects that states have funded with the Railway-Highway Crossings Program (RHCP) and what a subset of states reported about grade crossing improvements, (2) stakeholders’ perspectives on RHCP changes made by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and how these changes may affect state safety improvements for grade crossings, and (3) technical assistance the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) provided to states improving grade crossing safety and how FHWA could strengthen this assistance. The focus of our review is on public, at-grade, railway-highway grade crossings—where roads and railroad tracks intersect at the same level.[43] We did not include private grade crossings in our review, because projects at these crossings are not eligible for RHCP funding.

For all objectives, we reviewed our prior grade crossing and related railway and highway safety work.[44] We also reviewed other federal, state, and other stakeholder reports related to RHCP and grade crossing safety issues. For example, we reviewed a 2020 report with perspectives from a sample of stakeholders on changes that would improve RHCP.[45] We reviewed applicable statutes, regulations, FHWA guidance on RHCP, and other documents.

We also selected a nongeneralizable sample of six states—Alabama, Delaware, Florida, Indiana, Texas, and Washington—for in-depth review. We selected this sample based on (1) the level of RHCP funding received by the state in fiscal year 2023, to ensure a mix of states with high, medium, and low levels of funding; (2) the average number of grade crossing accidents from calendar years 2018 through 2022, to ensure a mix of states with high, medium, and low average number of accidents; (3) any notable efforts or unique challenges related to grade crossing safety, as identified by stakeholders we initially interviewed; and (4) geographic distribution of states—selected from the West, Midwest, South, and Northeast, as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Within each selected state, we identified and interviewed representatives from three stakeholder groups: (1) state departments of transportation central and district offices, when applicable; (2) county, city, public utilities, and other local entities; and (3) railroads.[46] We interviewed officials from the six selected states and local entities and railroads associated with 15 RHCP projects in our selected states to obtain perspectives on how RHCP changes may affect grade crossing safety projects. State and local perspectives are not generalizable. Further, we interviewed FHWA and Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) officials and railroad industry associations, such as the Association of American Railroads. See tables 1 and 2 for a complete list of entities we interviewed.

|

Federal Highway Administration |

Headquarters Alabama Division Office Delaware Division Office Florida Division Office Indiana Division Office Texas Division Office Washington Division Office |

|

|

Federal Railroad Administration |

Headquarters Grade Crossing Inspection Team (Florida) |

|

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107115

|

State |

Entities within the state |

Railroads within the state |

|

Alabama |

Alabama Department of Transportation |

Alabama and Tennessee River Railroad Norfolk Southern |

|

Delaware |

Delaware Department of Transportation Town of Laurel |

Delmarva Central Railroad |

|

Florida |

Florida Department of Transportation (Central and District 4 Offices) Miami-Dade County Department of Transportation and Public Works Orlando Utilities Commission Palm Beach County |

CSX South Florida Regional Transportation Authority |

|

Indiana |

Indiana Department of Transportation |

CSX Louisville & Indiana Railroad |

|

Texas |

Texas Department of Transportation (Central and Abilene District Offices) City of Abilene City of Stephenville Taylor County |

Fort Worth & Western Railroad Union Pacific Railroad |

|

Washington |

Washington State Department of Transportation Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission Yakima County |

Tacoma Rail |

|

Railroads* |

|

|

|

Amtrak |

||

|

BNSF Railway |

||

|

Brightline Florida |

||

|

Florida East Coast Railway |

||

|

Associations |

|

|

|

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials |

||

|

American Short Line and Regional Railroad Association |

||

|

Association of American Railroads |

||

|

Operation Lifesaver, Inc. |

||

Legend:

*=We interviewed these railroads to discuss their perspectives on the Railway-Highway Crossings Program (RHCP) changes made under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. These railroads may not have been associated with, or addressed, specific RHCP projects.

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107115

For all objectives, we visited Florida and Texas to observe and discuss selected safety improvements with state, local, and railroad stakeholders that planned to use or used RHCP funds and what FHWA technical assistance they used or needed for projects. We also observed an FRA grade crossing safety inspection group coordinating with state and local officials in Florida to identify and document risks at eight grade crossing locations around the Fort Lauderdale area. In addition, we observed a state grade crossing diagnostic team in Texas coordinate, inspect, and discuss inspection findings with relevant local and railroad entities at four grade crossing locations between Terrell and Dallas.

To describe projects states funded with RHCP and what a subset of states reported about grade crossing improvements, we reviewed key documents such as states’ railway-highway grade crossing program annual reports and action plans. Specifically, we reviewed the 2023 RHCP annual reports—the most recently available annual reports at the time of our review—for all 50 states and the District of Columbia to understand how states identified and evaluated projects and common challenges or notable efforts to address grade crossing safety. We also reviewed grade crossing safety action plans for our six selected states—Alabama, Delaware, Florida, Indiana, Texas, and Washington—to understand what information states used to identify high-risk crossings and select grade crossing projects and grade crossing safety challenges each state faced.

We reviewed and analyzed nationwide FRA data on grade crossing accidents and incidents, including injuries and fatalities, from calendar year 2014 through calendar year 2023.[47] To better understand trends we identified, we reviewed data from FRA’s Form 6180.57 Highway-Rail Grade Crossing Accident/Incident Reports, which railroads must submit to report each crossing accident.

We also reviewed FHWA’s nationwide compilation of grade crossing project data the 50 states and the District of Columbia submitted between 2019 and 2023 as part of their RHCP annual reports. Each of these reports includes (1) a list of projects that the state obligated RHCP funding for that year; and (2) a list of RHCP projects completed in prior years, along with the number of crashes that occurred at that grade crossing before the project started and after the project ended.[48] Specifically, we reviewed data for about 6,260 current year projects and about 6,120 prior year projects.[49]

We analyzed the number and type of current RHCP projects states reported each year, as well as the number of current projects reported across all 5 years. Additionally, for prior projects, we calculated the number of crashes reported by states at the project crossings before and after completion. We then compared the total number of crashes before completion with the total number of crashes after completion reported by all projects in a year. We also calculated the change in crashes from before completion to after completion for each project. Specifically, we calculated before-and-after crash data by summing all injuries crashes (which include crashes with fatalities and those with serious injuries) and property damage only crashes reported by states to FHWA in their annual reports. We used these calculated data to group projects based on the difference in the number of crashes before-and-after: (1) projects with zero crashes (both before-and-after), (2) projects with no change in crashes (e.g., two crashes before, two crashes after), (3) projects with a decrease in crashes, and (4) projects with an increase in crashes.

When evaluating past project effectiveness, FHWA guidance provides that states should report a minimum of 3 years of crash data prior to a project improvement and should include 3 years of data after an improvement project has been completed. However, states sometimes used less or more than 3 years of pre- or postproject crash history, ranging from 1 to 10 years of data. To ensure comparability in our analysis of crash data, we reported projects that were part of the three largest groups: those with 5 years of crash data before and after; those with 3 years of data before and after; and those with 5 years of data before and 3 years after project completion. The total number of projects was 2,389. Because only some states used the selected before-and-after periods, 42 unique states are represented in the subset of states included in this analysis. The number of states in the subset varied from 30 to 36 each year.

Under FHWA guidance, states have discretion to pick a reporting period for their RHCP annual report. States’ options for periods include reporting projects for the federal fiscal year, the state’s fiscal year, or the calendar year. FHWA reporting guidelines specify that states should use the same reporting period year to year. When compiling RHCP information for reports to Congress in previous years, FHWA combined information on the number and type of projects from states, regardless of the date range used. We also followed this practice in our report. To account for the different date ranges used by states, we defined the projects as submitted for a “report year.” Table 3 summarizes the different date ranges reported by each state for reporting year 2023.

|

Time period |

Dates |

States |

|

State fiscal year |

July 1, 2022 – June 30, 2023 |

Arkansas, California, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin |

|

September 1, 2022 – August 31, 2023 |

Texas |

|

|

April 1, 2022 – March 31, 2023 |

New York |

|

|

Calendar year |

January 1, 2023 – December 31, 2023 |

Hawaii |

|

January 1, 2022 – December 31, 2022 |

Indiana, Maine, Maryland, South Dakota, Washington |

|

|

January 1, 2016 – December 31, 2016 |

Florida |

|

|

Federal fiscal year |

October 1, 2022 – September 30, 2023 |

Alaska, Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, Oregon, Rhode Island, Utah, Washington, D.C. |

|

October 1, 2021 – September 30, 2022 |

Alabama, Arizona, Connecticut, Idaho, New Jersey, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Wyoming |

Source: GAO analysis of Railway-Highway Crossings Program (RHCP) annual reports. | GAO‑25‑107115

Further, we reclassified the project information in the RHCP annual reports. In these reports, FHWA guidance provides that states should describe the project type and crossing type. The project type field includes seven categories, such as eliminating a crossing or installing lights and gates. The crossing type field describes whether the project occurred at a crossing that already had active devices, such as bells, lights, or gates; a crossing with passive warning devices, such as signs or pavement markings; or an overpass or underpass. Together, these fields presented 17 possible combinations of project and crossing types. To simplify reporting, we reclassified projects into one of seven categories based on both the project type and crossing type fields. We also combined some FHWA project types based on the small number of projects of each type reported. These combinations allowed us to provide more precise categories for work that involved installing active devices, while simplifying categories that were similar in the type of work performed and funding required. Table 4 summarizes these combinations.

|

Project type |

Crossing type |

GAO category |

|

Active grade crossing equipment installation/upgrade |

At-grade passive warning devices |

Passive-to-active |

|

Active grade crossing equipment installation/upgrade |

At-grade active warning devices |

Upgrading existing active devices |

|

Active grade crossing equipment installation/upgrade |

Nonmotorized passive warning devices |

Adding active devices at pedestrian trail-railway crossings |

|

Active grade crossing equipment installation/upgrade |

Nonmotorized active warning devices |

|

|

Grade crossing elimination |

At-grade passive warning devices |

Eliminating crossings |

|

Grade crossing elimination |

At-grade active warning devices |

|

|

Grade crossing elimination |

Grade-separated RR over road |

|

|

Grade crossing elimination |

Grade-separated RR under road |

|

|

Crossing approach improvements |

At-grade passive warning devices |

Improving roadway approach and alignment |

|

Crossing approach improvements |

At-grade active warning devices |

|

|

Roadway geometry improvements |

At-grade passive warning devices |

|

|

Roadway geometry improvements |

At-grade active warning devices |

|

|

Crossing Warning Sign and pavement marking improvements |

At-grade passive warning devices |

Improving pavement markings and visibility |

|

Crossing Warning Sign and pavement marking improvements |

At-grade active warning devices |

|

|

Visibility improvements |

At-grade passive warning devices |

|

|

Visibility improvements |

At-grade active warning devices |

|

|

Crossing inventory update |

|

Updating crossing inventory information |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Highway Administration information. | GAO 25-107115

To assess the reliability of the project and crash data, we reviewed FHWA’s guidance for reporting requirements and past reports to Congress that used these data, interviewed FHWA officials, and electronically tested the data to assess quality and completeness. We found that the RHCP project data were sufficiently reliable to provide an approximate national count of projects obligated in a year, as reported by states, with some limitations. Additionally, we found the data were sufficiently reliable to support an analysis of crashes reported by a subset of states for past projects, including the approximate number of crashes that occurred before and after grade crossing project completion, with some limitations.

According to FHWA officials, RHCP project data is self-reported by state departments of transportation, which rely on different data sources, including FRA accident reports and local police reports. This variability in data collection methods may result in inconsistencies in reported data at the state level. As a result, the state-reported number of projects that were funded using RHCP funds may be overstated. In addition, our analysis of state-reported project data may overestimate the total number of projects that reported no accidents both before and after the project was completed, or a decrease in accidents after project completion.

Further, the total numbers of crashes we reported are based on the annual report data that states reported to FHWA. We identified inconsistencies with how states entered data into a field in FHWA’s database—about “other crashes”—so we did not include this field in our crash analysis. As a result, our analysis may exclude some crashes that states did not classify as injury crashes or property damage crashes. We did not independently verify any state-reported data.

To describe stakeholders’ perspectives on RHCP changes and how these changes may affect state safety improvements for grade crossings, we reviewed RHCP changes made under IIJA. These changes include

1. increasing the federal share of eligible RHCP project costs from 90 to 100 percent;

2. increasing the maximum incentive payment that a state may pay a local government for crossing closures from $7,500 to $100,000;

3. removing the 50 percent funding set-aside requirement for installing protective devices;

4. expressly providing that replacing certain functionally obsolete equipment is an eligible project expense; and

5. expressly providing that projects to reduce fatalities and injuries of pedestrian trespassers at grade crossings are eligible for funding.

We also selected RHCP projects—either planned, in-progress, or completed—by our six selected states to better understand the effect of the RHCP changes. Each of our six selected states identified RHCP projects within their state for our review. From these identified projects, we selected a total of 15 projects to review: two projects each from Alabama, Delaware, Indiana, and Washington; three projects from Texas; and four projects from Florida. We selected a mix of these projects using three primary factors: (1) whether the state reported the project was funded after the enactment of the IIJA; (2) whether the project was located in an urban or rural area, as determined by the state; and (3) the FHWA project type used by the state. We interviewed relevant state and local officials, and railroad representatives involved in these RHCP projects.

To identify technical assistance FHWA provided to states for improving grade crossing safety, we reviewed relevant guidance, webinars, and other information on the agency’s website. This included documents on RHCP and IIJA, made available to support states’ efforts to implement RHCP projects.[50] We also reviewed FRA’s railway-highway grade crossing safety and trespassing prevention information and other relevant technical resources available on its website. We also reviewed an FRA link on trespassing prevention that FHWA referred to in its Railway-Highway Crossings Program Questions & Answers Guidance.[51]

To examine how FHWA could strengthen its RHCP technical assistance, we assessed the different types of FHWA technical assistance and how the information directly addressed the five RHCP changes made under IIJA and provided clarification to help states better implement RHCP or identify RHCP projects. For example, for the RHCP change that made projects related to pedestrian injuries and fatalities from trespassing expressly eligible for funding, we reviewed and assessed FHWA’s technical assistance that addressed this change. We determined that internal controls were significant to this review. We compared the technical assistance information FHWA makes available to states for implementing RHCP projects with Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government—specifically, the principle for communicating the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[52]

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

The Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) administers the formula funding for the Railway-Highway Crossings Program (RHCP), which supports states in eliminating hazards and implementing safety improvement projects at public railway-highway grade crossings, among other things. States use state action plans for railway-highway grade crossings to identify specific strategies to improve safety at their crossings.[53] Described below are the prioritization processes our six selected states—Alabama, Delaware, Florida, Indiana, Texas, and Washington—used to select RHCP projects. This includes illustrative examples of planned or completed RHCP projects that these states expect to improve safety at high-risk crossings.

Alabama

Prioritization Process

Alabama’s 2019 grade crossing state action plan described its prioritization process as data driven, using a priority ranking formula that relied on 5 years of crash history. According to the plan, Alabama used predictive performance measures, such as crossing type; highway traffic volume; and total train volume, as well as the results of state grade crossing diagnostic reviews to select projects.[54] According to Alabama officials, they select up to 30 RHCP projects annually and prioritize state highway projects.

Project Examples

Alabama officials described one project—the Bayou Avenue East Crossing in Satsuma—that was fully funded by RHCP following the enactment of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA).[55] This project was managed by Norfolk Southern Railroad in partnership with the Alabama Department of Transportation. It upgraded the crossing from flashing lights to a more comprehensive warning system with upgraded flashing lights and gates. The upgrade also included installing constant warning time technology, which provides consistent signal timing as trains approach to enhance safety. Officials determined that the existing equipment was obsolete because it dated back to the 1980s, making this upgrade critical for improving the crossing’s reliability and safety.

Alabama officials also used RHCP funding to install delineators at grade crossings. Delineators are used to prevent vehicles from turning onto railroad tracks and driving around lowered grade crossing gates (see fig. 9). Delineators can also direct pedestrians away from dangerous areas near the tracks, encouraging safer crossing behaviors.

Figure 9: Completed Railway-Highway Crossing Program Project in Alabama That Installed Delineators at Two Different Grade Crossings

Delaware

Prioritization Process