WATERSHED DAMS

Better Program Management Would Improve Safety

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Andrew Von Ah at vonaha@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107404, a report to congressional requesters

Better Program Management Would Improve Safety

Why GAO Did This Study

NRCS assisted in the designing, planning, and construction of nearly 12,000 watershed dams to control flooding and prevent damage to communities. Most of these dams were built between 1954 and 1980 in rural, agricultural areas of the U.S. As these dams have aged and surrounding areas have developed, stakeholders are concerned about the safety of the dams.

GAO was asked to review how NRCS manages dam safety. This report assesses the extent to which (1) NRCS has implemented its dam safety responsibilities, and (2) NRCS’s processes for funding dam projects under REHAB are transparent.

GAO reviewed NRCS policies, guidance, and data, as well as relevant federal laws and regulations. GAO selected a nongeneralizable sample of 25 dams in five states based on condition, geography, and other factors. For these dams, GAO reviewed documentation and interviewed project sponsors. GAO conducted site visits at 10 of these dams in three states and interviewed officials from NRCS, state dam safety offices, and other stakeholders.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that NRCS take steps to (1) monitor project sponsors’ compliance with operations and maintenance requirements; (2) collect and verify key dam data; (3) communicate key information to project sponsors about REHAB funding opportunities; and (4) document the rationale for its decisions to advance REHAB applications for funding. USDA agreed with GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) has a variety of dam safety responsibilities but has not consistently implemented them. NRCS assists project sponsors—typically local governments—in designing, planning, constructing, and rehabilitating watershed dams. Sponsors are responsible for safely operating and maintaining dams according to federal, state, local, and tribal laws and regulations. NRCS’s responsibilities include (1) monitoring sponsors’ compliance with operation and maintenance requirements, and (2) maintaining a national data inventory of NRCS-assisted dams. However, NRCS has not consistently reviewed operation and maintenance agreements with sponsors every 5 years or monitored the timely completion of dam inspections. As a result, 32 percent of significant- and high-hazard dams within their evaluated lives were past their required inspection due date, as of August 2024. In addition, key safety information NRCS collects—such as the condition of some dams—is missing or inaccurate. Without complete and accurate data, NRCS cannot ensure the safe operation and maintenance of dams across the country that help protect communities from flooding.

In addition, GAO found that some of NRCS’s processes for funding rehabilitation projects are not fully transparent. NRCS’s Watershed Rehabilitation Program (REHAB) provides project sponsors with funding to rehabilitate their dams, to help meet safety and performance standards. However, NRCS has not fully communicated to project sponsors key information related to funding availability, eligibility, or the types of projects to be funded. Sponsors for eight of the 25 dams GAO met with said they were either unaware of REHAB or unclear about the requirements for receiving funding. Without improved communication about the program, project sponsors may continue to miss opportunities to address critical safety issues. Additionally, for fiscal year 2024, NRCS did not document why its state offices advanced some applications to headquarters for funding consideration and not others. NRCS officials said the specific rationale for prioritizing some projects over others can vary by state. Without guidance for NRCS state offices to document the rationale for these decisions, NRCS cannot ensure it allocates funds in a consistent and transparent manner that aligns with agency goals to protect lives, property, and infrastructure.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

NRCS |

Natural Resources Conservation Service |

|

REHAB |

Watershed Rehabilitation Program |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

July 17, 2025

The Honorable Ron Johnson

Chairman

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Margaret Wood Hassan

United States Senate

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) assisted in the designing, planning, and construction of nearly 12,000 watershed dams (dams) to control flooding and prevent damage to communities. Most of the dams were built between 1954 and 1980 and initially classified as “low hazard,” meaning they were located in rural or agricultural areas where their failure could have damaged farm buildings, agricultural land, or township or country roads. However, due to downstream residential and commercial development, the hazard classification of many dams has increased. In addition, nearly 60 percent of NRCS dams will have reached the end of their evaluated life by the end of 2025.[1] Dams also may have deteriorated due to their age, mis-operation, inadequate maintenance, climate-related events, or other factors. As a result, stakeholders have expressed concern about whether some dams meet current state or federal safety requirements.

NRCS supports project sponsors—the nonfederal entities such as local governments that own the dams—in operating and maintaining them. To address the safety of these aging dams, NRCS provides technical and financial assistance to sponsors. Through its Watershed Programs, NRCS helps sponsors plan, design, construct, and rehabilitate the dams.[2] Specifically, through its Watershed Rehabilitation Program (REHAB), NRCS provides funding to sponsors to rehabilitate their dams, to extend the dams’ evaluated life and help them meet safety and performance standards.

You asked us to examine how NRCS manages dam safety. This report assesses the extent to which (1) NRCS has implemented its safety responsibilities for Watershed Program dams, and (2) NRCS’s processes for funding dam projects under REHAB are transparent.

For both objectives, we reviewed NRCS’s policies and guidance related to its Watershed Programs. We selected a nongeneralizable sample of 25 dams in five states (Indiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, Texas, and West Virginia) based on a variety of factors, including hazard classification, dam condition, and geography. For our selected dams, we collected and reviewed information from NRCS’s dam files, including operation and maintenance agreements, inspection reports, and REHAB assessment reports. We also visited 10 dams and interviewed project sponsors, state dam safety officials, officials from NRCS headquarters and state offices, and other stakeholders about how NRCS monitors the safety of dams.

To assess the extent to which NRCS has implemented its safety responsibilities for dams built under its Watershed Programs, we reviewed NRCS’s operation and maintenance policies, including those related to communicating, documenting, and enforcing its monitoring activities. We reviewed documentation for the case files of the 25 selected dams to assess the extent to which NRCS has implemented its policies for monitoring project sponsors’ adherence to operation and maintenance requirements. We compared NRCS’s efforts with Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government—specifically, the principles that management should develop and maintain documentation of its internal control system, and that agencies should identify deficiencies through monitoring activities and determine appropriate corrective actions to remedy deficiencies.[3]

In addition, as part of our review of NRCS’s implementation of its dam safety responsibilities, we evaluated the extent to which NRCS has collected and used data on dams to manage their safety. We reviewed NRCS’s policies related to data collection and analyzed NRCS’s GeoObserver dam inventory data (dams data), which include information on dams’ characteristics, structural specifications, hazard classifications, and inspection dates. We evaluated the completeness (i.e., whether specific fields included required information) and accuracy of these data and determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our report. We compared our analyses with NRCS’s data collection and maintenance policies to assess the extent to which NRCS implemented its policies. We also compared our analyses with federal standards for internal control, specifically the principles that management should obtain relevant data from reliable sources and process data into quality information.[4]

To assess the extent to which NRCS’s processes for funding dam projects under REHAB are transparent, we reviewed NRCS’s policies and guidance for communicating funding availability, evaluating applications, and communicating award decisions for fiscal year 2024. We compared NRCS’s processes with its policies and guidance for providing federal financial assistance. We also compared NRCS’s processes with federal standards for internal control—specifically, the principles that management should (1) externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives, (2) internally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the program’s objectives, and (3) maintain documentation of its internal control system.[5] In addition, we compared NRCS’s processes with a leading practice on communicating information with potential applicants prior to the application process.[6] Additional information on our scope and methodology can be found in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

History and Characteristics of Watershed Dams

According to the National Inventory of Dams, as of April 2025, there were over 92,000 dams in the United States, of which nearly 13 percent (about 11,850 dams) are collectively known as NRCS Watershed Program dams.[7] These dams are federally assisted, not federally owned, with few exceptions.[8] The first dam was built in Oklahoma in 1948 under the act commonly known as the Flood Control Act of 1944.[9] After the Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Act was enacted in 1954, NRCS began rapid construction of dams; between 1955 and 1980, NRCS built 51 percent of the 11,856 dams.[10] According to NRCS, these dams reduce flooding and erosion damage, provide an estimated $2.2 billion annually in benefits, and improve wildlife habitat, recreation, and water supply.

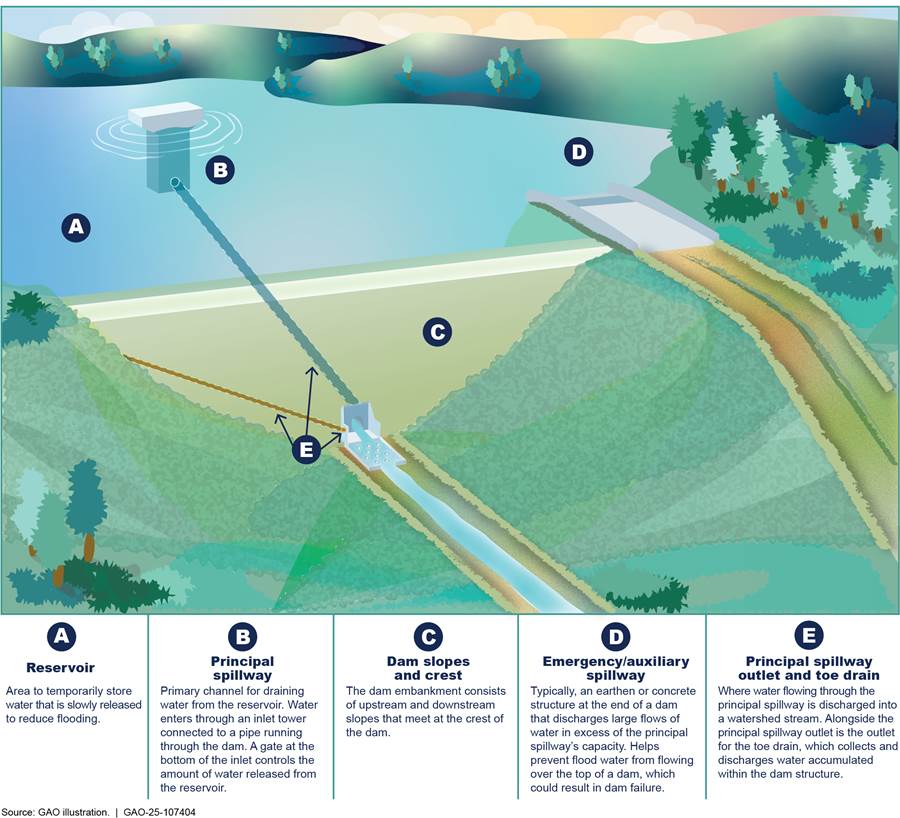

Most NRCS-assisted dams are earthen and were built in rural, agricultural areas to control flooding, prevent damage to communities, and provide drinking water or recreation, among other purposes. Generally, the dams store rainwater in a reservoir following rainstorms, and slowly release the water over several days through the principal spillway pipe that runs through the dam (see fig. 1). This process was designed to reduce the rate of runoff that reaches streams and land downstream, helping to prevent damaging floods and erosion. The dams also have an auxiliary or emergency spillway designed to prevent water from overtopping the crest of the dam, which could result in dam failure.

Roles of NRCS and Project Sponsors

Before NRCS provides funds for the dams’ construction, NRCS and project sponsors enter into contractual agreements that outline the responsibilities of both NRCS and sponsors for ongoing operation and maintenance of the dams. In general, sponsors must own or have a legal right to use the land on which dams are situated, and they are responsible for safely operating and maintaining the dams, according to NRCS’s requirements and other applicable federal, state, local, and tribal laws and regulations.[11] NRCS works with sponsors through its state and district offices located in each state.[12] In general, NRCS’s role is to ensure sponsors are adequately operating and maintaining their dams and adhering to their contractual agreements with NRCS. NRCS does not provide funding for operation and maintenance.

Project sponsors are responsible for operating and maintaining the dam as long as the dam exists. Sponsors must have access rights to the dam if it is on private property, power of eminent domain, and the authority to levy taxes, among other responsibilities. Because of these requirements, government entities, such as county or municipal governments, generally serve as sponsors. However, local government sponsors often partner with special-use districts (e.g., conservation districts, watershed districts, or drainage districts) to operate and maintain the dams. Following the expiration of the contractual agreements—which occurs when dams reach the end of their evaluated life—the federal interest ceases and NRCS no longer has a role in overseeing sponsors’ operation and maintenance of the dams.

Hazard Classifications and Safety Concerns

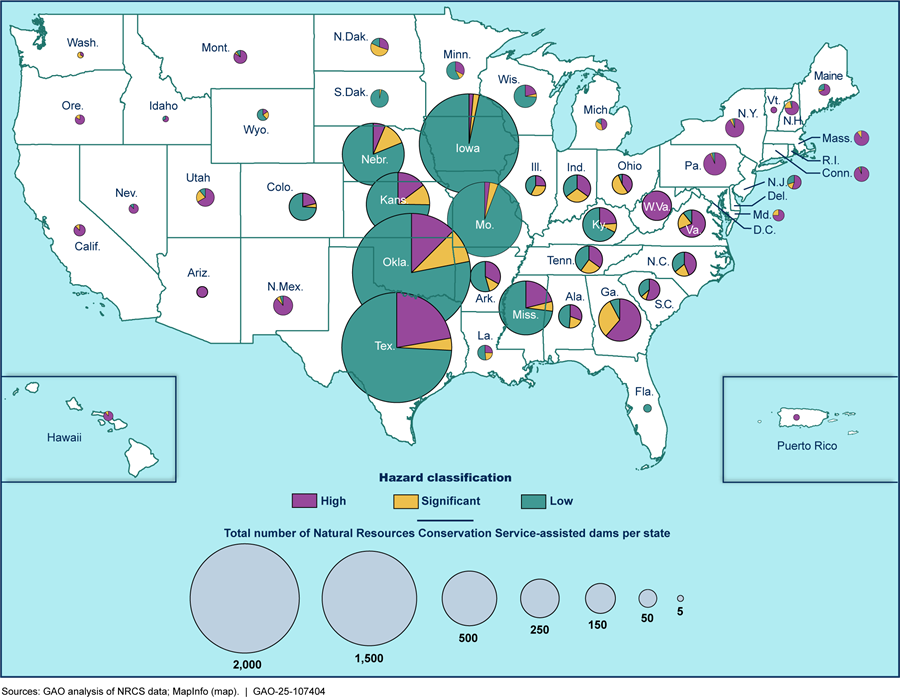

Most of the dams are classified as having low-hazard potential. Dams can also be classified as having significant- or high-hazard potential, the latter meaning that failure or mis-operation may cause loss of life or serious damage to homes, industrial or commercial buildings, important public utilities, main highways, or railroads. There are 8,345 low-hazard, 1,037 significant-hazard, and 2,474 high-hazard dams throughout the United States, according NRCS data as of August 2024 (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Map of Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Watershed Dams by Hazard Classification

Note: There are no NRCS watershed dams in Alaska.

Watershed Rehabilitation Program

To address changes in hazard classification, dam age, and other concerns, NRCS provides financial assistance to rehabilitate dams to ensure they remain safe and continue to function as designed. In 2000, legislation authorizing the Watershed Rehabilitation Program (REHAB) was enacted to help rehabilitate aging dams that are reaching the end of their evaluated life and to help them meet safety and performance standards.[13] REHAB, which is funded through annual appropriations and a permanent appropriation, provides funding to project sponsors through cooperative agreements to address dam deterioration and make upgrades necessitated by changes in dams’ hazard classifications.[14] Only dams constructed under certain U.S. Department of Agriculture programs are eligible for REHAB assistance, and the sponsor must request funding.[15] According to NRCS, as of October 2024, NRCS had rehabilitated 183 dams since REHAB was first funded in 2002. See figure 3 for an example of a dam rehabilitation project.

Note: This Georgia dam was built in 1965 and rehabilitated in 2024 to meet safety standards due to significant residential and commercial development downstream. The rehabilitation project included replacement of the auxiliary spillway (center of image) with reinforced concrete.

NRCS provides phased funding for REHAB projects for four phases of dam rehabilitation: REHAB assessment, planning, design, and construction. NRCS covers 100 percent of the costs associated with the first three phases and 65 percent of the costs associated with construction.

· Assessment. To begin the funding process, a project sponsor typically requests that NRCS conduct a REHAB assessment to determine whether the dam is eligible and would benefit from REHAB.[16] Assessments include information on a dam’s condition, the dam’s risk index (i.e., the risk of loss of life and property should the dam fail), and estimated rehabilitation costs. In addition, assessments include information on operation and maintenance deficiencies, changes in hazard classification, and dam failure analyses. Assessments may include an initial analysis of alternatives and recommendations.

· Planning. NRCS state offices help with the preparation of a watershed project plan with project sponsors. The plan outlines the work necessary to extend the life of the dam and for the dam to meet all applicable safety and performance standards. NRCS determines the scope and estimated cost for the work, develops a cost-benefit analysis of alternatives (including decommissioning), reports on sponsors’ compliance with operation and maintenance requirements, and analyzes potential ways the dam could fail, among other things.[17]

· Design. NRCS state offices help with the development of the technical design of the project. NRCS might hire architectural or engineering firms to assist in the development of the design, and state dam safety offices might also assist, for example, by reviewing design plans and issuing permits.

· Construction. NRCS state offices help manage the construction contracts for work detailed in the planning and design phases. State dam safety offices might also provide technical assistance for dam construction. For the construction phase, costs are shared between NRCS (65 percent) and the project sponsor (35 percent).

NRCS Has Not Consistently Implemented Its Dam Safety Responsibilities

NRCS has a variety of dam safety responsibilities, including providing technical assistance to project sponsors, collaborating with state dam safety offices, monitoring sponsors’ operation and maintenance activities, and maintaining a national database of dams in its portfolio. However, we found that NRCS has not consistently followed its policies that outline its responsibilities for ensuring dam safety, and that some of the safety-related information in its dams database is incomplete or inaccurate.

NRCS Assists with and Monitors Operation and Maintenance Activities but Has Not Consistently Followed Its Own Policies

NRCS’s primary responsibilities for dam safety include (1) providing project sponsors with technical assistance, (2) collaborating with state dam safety offices, and (3) monitoring sponsors’ compliance with requirements for operating and maintaining the dams. NRCS officials told us that dam safety responsibilities lie principally with sponsors and with state dam safety offices, which regulate the safety of these dams.[18]

NRCS’s technical assistance to project sponsors includes helping with inspections, conducting dam assessments, and other activities. According to NRCS’s policies, sponsors must have their dams inspected according to relevant federal and state regulations, which determine the type and frequency of inspections.[19] For example, NRCS requires sponsors of significant- and high-hazard dams that are still within their evaluated life to have their dams formally inspected at least once every 5 years. NRCS officials told us their state offices may conduct inspections upon sponsors’ request. NRCS also conducts dam assessments, which help sponsors understand the condition of their dams and whether the dams may be eligible for REHAB. NRCS officials said that, as of April 2025, staff had conducted over 1,995 dam assessments since 1999. In addition, NRCS provides engineering assistance and other site-specific guidance to address safety concerns, as needed and requested by sponsors. For example, one sponsor told us that NRCS had recently sent an engineer to help investigate water seepage in a dam, and that NRCS had assisted with issues of encroachment on dam easements and by conducting camera inspections of spillway pipes.

NRCS also collaborates with state dam safety officials on a variety of issues pertaining to dams. NRCS officials told us that state dam safety offices regulate dams, and that NRCS relies on state dam safety offices to exercise their regulatory authorities to ensure project sponsors are safely operating and maintaining their dams. NRCS officials said they usually coordinate with state dam safety offices on dam inspections. Officials from four of the five state dam safety offices we interviewed said they have regular meetings with NRCS to share information about various issues, ongoing or planned projects, and the assistance each party may need or be able to provide. Additionally, officials from two state dam safety offices said that NRCS has held trainings on topics such as conducting inspections, and officials from one state dam safety office said NRCS staff have presented on funding opportunities at conferences.

In addition, according to its policy manuals, NRCS is to monitor project sponsors’ compliance with requirements for operating and maintaining the dams by (1) reviewing operation and maintenance agreements made between NRCS and sponsors; (2) monitoring formal dam inspections; and (3) investigating sponsors’ potential violations of operation and maintenance requirements.[20] However, NRCS has not consistently followed these policies.

Reviewing operation and maintenance agreements. According to NRCS’s policy, district NRCS officials are responsible for reviewing operation and maintenance agreements with project sponsors at least once every 5 years. The purposes of these reviews include discussing sponsors’ responsibilities, their financial needs, and any need to revise the agreements. According to an NRCS state official, these reviews provide an opportunity for NRCS to educate sponsors on their responsibilities and help address any issues they may face.

However, for the 25 dams we selected, we found that NRCS has not consistently reviewed operation and maintenance agreements with project sponsors every 5 years. Additionally, sponsors of several dams we selected said they did not recall NRCS reviewing their operation and maintenance agreements with them. One official from an NRCS state office told us that district staff were not reviewing these agreements with sponsors, and that even finding the original agreement documents could be difficult. NRCS was unable to provide the operation and maintenance agreement for seven of the 25 dams whose case files we reviewed.

As a result, when we interviewed project sponsors, some stated they were not fully aware of their operation and maintenance responsibilities. For example, a representative from one sponsor told us they did not regularly conduct activities required by their operations and maintenance agreement, such as mowing the grass and clearing debris. The representative said there had always been an unspoken understanding that the owner of the land on which the dam was located would assume some of these responsibilities. A representative from another sponsor was unaware that it, among other parties, could potentially be liable for damages should its dam fail because of inadequate operation and maintenance or other issues.

Monitoring formal dam inspections. According to NRCS’s policy, NRCS-assisted dams that are still within their evaluated lives must comply with NRCS’s inspection requirements. According to NRCS’s operation and maintenance policies, project sponsors of significant- and high-hazard dams must have their dams formally inspected at least once every 5 years.[21] The purpose of formal inspections is to determine the structural integrity of the dams and whether the dams meet current NRCS and other applicable regulatory criteria. After conducting the formal inspection, the inspector drafts a report that should include an inspection checklist, photographs, and descriptions of any identified deficiencies and required corrective actions. According to NRCS’s policy, formal inspection reports should be sent to NRCS state offices for review, approval, and retention.

However, we found that NRCS did not consistently monitor formal dam inspections. Specifically, we found that the files for eight of the 12 significant- and high-hazard dams we selected that were still within their evaluated lives did not include a formal inspection report from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023.[22] According to our analysis of NRCS’s dams data, as of August 1, 2024, 32 percent of the significant- and high-hazard dams still within their evaluated lives (473 dams) were past their required inspection due date.[23] On average, the inspections for those dams were 3 years past their required due date. Additionally, some formal inspection reports we reviewed were incomplete. For example, formal inspection reports for seven dams we reviewed were missing key information, such as data the inspector reviewed and analyzed for the inspection, an evaluation of the data the inspector collected, or a determination of whether the dam met current NRCS and regulatory criteria.

Investigating sponsors’ potential violations of operation and maintenance requirements. According to NRCS’s policy, NRCS state offices are responsible for ensuring state or district staff investigate all suspected violations of operation and maintenance requirements and communicate with project sponsors about violations.[24] NRCS’s policy states that violations of operation and maintenance requirements include issues that may prevent the dam from functioning as intended or create a health or safety hazard. Potential violations could include a lack of compliance with structural regulatory criteria due to an increase in a dam’s hazard classification, or serious damage to the dam’s structure caused by, for example, dense tree growth.

According to NRCS’s policy, when the agency determines a violation has occurred, it is to notify the project sponsor of the violation in writing, and include actions needed to address the violation and a time frame for doing so. NRCS’s policy further states that if the NRCS state office determines the sponsor has failed to address the violation, the office is to take actions to protect the interests of the government and public. These actions could include deeming the sponsor ineligible for potential future REHAB and other program funding until the sponsor meets all operation and maintenance requirements; requiring that the sponsor reimburse the government for any financial assistance provided; and correcting any deficiencies and recovering the costs from the sponsors.

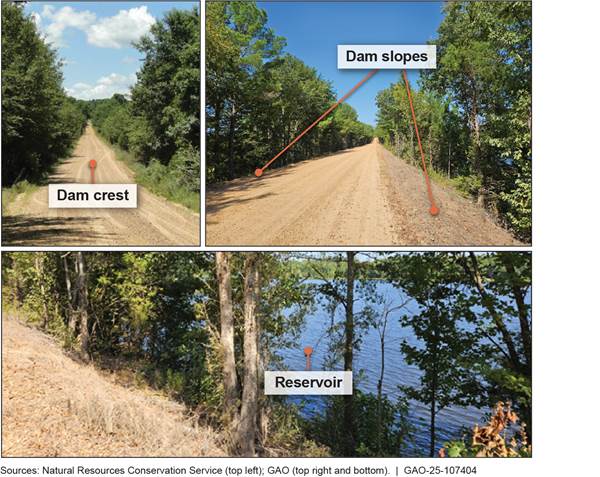

Among the 12 selected dams that were still within their evaluated lives during our review period of fiscal years 2019 through 2023, we identified two dams whose inspection reports indicated potential violations of operation and maintenance requirements. However, in our review of these dams’ files, we found no evidence that NRCS had investigated or taken corrective actions to address those violations. For example, in a July 2017 inspection report for a dam in Mississippi, officials noted that the vegetation on the dam’s slopes was “too dense to inspect for other problems.” Heavy vegetation on dam slopes poses a problem for the dam itself, as roots may destabilize the dam, and the overgrowth prevents clear lines of sight to be able to detect other potential issues. However, NRCS did not include recommended corrective actions in the inspection report. When we visited the dam in August 2024, we observed that the dam’s slopes were covered in dense vegetation (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Embankment of Natural Resources Conservation Service Watershed Dam with Heavy Vegetation, Mississippi, 2017 (top left) and 2024 (top right and bottom)

Although NRCS’s policies define the agency’s responsibilities for monitoring project sponsors’ compliance with operation and maintenance requirements, NRCS does not have mechanisms to ensure its state and district offices consistently follow these policies. For example, NRCS does not have policies for documenting meetings to review operation and maintenance agreements, or for reviewing dams’ case files to ensure they contain all required documents (e.g., operation and maintenance agreements and formal inspection reports). Instead, NRCS headquarter officials said that they rely on state-level staff to understand and follow agency policies, and that they provide training to state offices on their policies. However, we reviewed NRCS training materials and found that they did not provide specific information on state officials’ responsibilities for monitoring compliance with operation and maintenance requirements.

NRCS officials also told us that NRCS is not a regulatory agency and therefore not responsible for monitoring project sponsors’ compliance with operation and maintenance requirements or for pursuing actions to enforce compliance. According to the officials, these are the responsibilities of state dam safety offices. However, NRCS’s policy states that its monitoring and enforcement of operation and maintenance requirements is necessary to ensure public health and safety. Additionally, federal standards for internal control state that management should develop and maintain documentation of its internal control system, and monitor and evaluate its internal control system and remediate any identified deficiencies. Without mechanisms to ensure that state and district staff consistently implement policies and procedures for monitoring sponsors’ compliance with operation and maintenance requirements, NRCS cannot ensure the continued safety of the dams in its portfolio.

NRCS Collects Information Related to Dam Safety but Has Not Verified Its Completeness or Accuracy

NRCS collects a variety of data to help it manage its portfolio of dams, such as information related to dams’ physical characteristics and safety, but some of its data are incomplete or inaccurate. According to NRCS’s policy, the agency must maintain an inventory of its dams.[25] In addition, NRCS policy further provides that as a participant in the National Inventory of Dams, NRCS collects a subset of these data to report to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. In addition, federal standards for internal control state that management should obtain relevant data from reliable sources and process data into quality information.[26]

NRCS’s database contains a variety of information on its dams’ physical and other characteristics, such as location, ownership, year completed, and structural dimensions. The database also includes data relevant to the safe operation and maintenance of the dams, including hazard classification, condition for high-hazard dams, and the date of the dams’ last inspection. NRCS officials said they use the information in its database to track inspections, modifications made to the dams, and whether dams have an emergency action plan in place and when it was last updated, among other purposes.

However, we found that NRCS’s dams database was incomplete and contained inaccurate information, including safety-related information. Specifically, we found that data on the condition, date of last inspection, and owner’s name were missing or inaccurate.

· Condition. In our analysis of NRCS’s dams database, we found that 84 percent of the 2,474 high-hazard dams in NRCS’s inventory were missing a condition assessment value. According to the data dictionary for NRCS’s dams database, NRCS is to collect information on the condition for all high-hazard dams. This assessment describes the condition of a dam based on the presence and severity of any dam safety deficiencies, which are generally defined as characteristics of dams that do not meet applicable minimum regulatory criteria and may risk dam failure. NRCS uses four condition values that range from “satisfactory” (no existing or potential dam safety deficiencies are recognized) to “unsatisfactory” (a dam safety deficiency is recognized that requires immediate or emergency remedial action).[27] Without including these values in its dams database, NRCS may be unaware of dams that could pose immediate danger to lives and property, and may not understand the extent to which dams in its portfolio need to be rehabilitated.

· Date of last inspection. We found that over half of all dams in NRCS’s dams database either did not have a date of last inspection or had an anomalous value.[28] Additionally, we found that the values for the date of last inspection were either missing or inaccurate for nearly half of all significant- and high-hazard dams still within their evaluated lives.[29] As noted above, according to NRCS’s policy, project sponsors of significant- and high-hazard dams must have their dams formally inspected at least once every 5 years. Without complete and accurate data on inspections, NRCS cannot track inspections across its portfolio of dams to ensure sponsors are following NRCS’s policies and safely operating and maintaining dams, and that the condition information is up to date.

· Owner’s (i.e., project sponsor’s) name. We found that in NRCS’s dams database, about 400 (nearly 4 percent) of the dams sponsored by local government appeared to list a private individual’s name rather than a government entity as the project sponsor. NRCS officials told us that in some cases, the original sponsor no longer existed as an entity, so the landowner may be the only point of contact. According to NRCS officials, it is important that the agency have accurate data on sponsors so it can contact them in case of emergency. NRCS regulation states that sponsors must have power of eminent domain and the authority to levy taxes, among other responsibilities, which private individuals do not have. Without accurate information on sponsors, or without sponsors with the authority to carry out certain functions, NRCS cannot ensure these dams are properly operated and maintained in emergency and other situations.

NRCS does not have a quality assurance plan or guidance for how state and district offices should collect and verify information in its dams database. NRCS officials told us they were aware of some issues with data completeness and accuracy in the database. More broadly, they said that insufficient staff resources have limited their ability to address challenges across the agency. However, NRCS’s policy requires the agency to maintain a national inventory of dams to manage overall dam safety, and to keep these data current and accurate.

In addition, NRCS officials told us they plan to create a risk management team to identify and assess the risks to dams across NRCS’s portfolio. This team will rely, in part, on the data in NRCS’s dams database to inform its work. However, without complete and accurate data on its portfolio of dams, the risk management team will face challenges in completing its work. By developing a quality assurance plan and guidance for how its offices should collect and verify information, NRCS will be better able to accurately assess risks in its portfolio and to carry out an effective dam safety program.

NRCS’s Processes for Funding REHAB Dam Projects Are Not Fully Transparent

NRCS Awards Funding for REHAB Dam Projects Through an Annual Application Process

NRCS headquarters and state offices facilitate the allocation of REHAB funding to various dam projects. NRCS officials told us that every fiscal year, headquarters sends a national bulletin to NRCS state offices with information about REHAB for use in outreach to project sponsors. Sponsors must submit REHAB funding requests to NRCS state offices sequentially by phase (assessment, planning, design, and construction).[30] For new projects, NRCS officials told us the application process begins with NRCS conducting a REHAB assessment, which determines whether the project is eligible for the program. If the assessment finds the project would benefit from REHAB, the NRCS state office sends copies of the assessment report to the sponsor as well as NRCS headquarters. For ongoing projects that have previously received REHAB funding for planning or design activities, sponsors reapply for funding for the next phase.

NRCS state offices then rank applications and forward them to NRCS headquarters for funding consideration, according to NRCS’s policy. For both new and ongoing projects, NRCS state offices are to evaluate applications by computing the risk index and to work with state dam safety officials to determine priority rankings.[31] According to NRCS’s policy, NRCS headquarters ranks all applications in each phase by their risk index and recommends projects for funding. NRCS’s manual directs officials to prioritize projects in the construction phase, followed by projects in the design, planning, and assessment phases.

After ranking the projects, NRCS selects project sponsors for awards. In fiscal year 2024, NRCS allocated about $36 million to 175 dam projects (see table 1). NRCS headquarter officials stated that they awarded funding to all the applications they received from NRCS state offices in fiscal year 2024.

|

REHAB phase |

Number of dams |

Funds allocated |

|

Assessment |

105 |

$3,595,415 |

|

Planninga |

41 |

10,032,373 |

|

Design |

16 |

2,670,158 |

|

Construction |

13 |

19,969,498 |

|

Total |

175 |

$36,267,444 |

Source: GAO analysis of Natural Resources Conservation Service data. | GAO‑25‑107404

Note: REHAB consists of four phases overseen by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, starting with a REHAB assessment to determine if a dam would benefit from rehabilitation. If so, then a project’s sponsor would apply for the planning, design, and construction phases to complete the rehabilitation project.

aIn fiscal year 2024, NRCS canceled one project to which it had allocated $1.2 million.

Following the awards, NRCS publicly communicates information on USAspending.gov. In fiscal year 2024, NRCS published federal award information for its REHAB funding distributions on USAspending.gov. This information included recipient name, total amount of funds obligated, federal award description, and period of performance start and end date. Additionally, NRCS officials told us that their agency was developing its own website to further communicate REHAB award information. NRCS officials stated that they expected the website to be operational in summer 2025.

NRCS’s Communication and Evaluation Processes for Funding REHAB Dam Projects Are Not Fully Transparent

We found that key elements of NRCS’s processes for funding REHAB dam projects in fiscal year 2024 were not fully transparent. Specifically, we found that NRCS did not fully or consistently communicate key information about REHAB funding opportunities to project sponsors, and that NRCS did not document key decisions related to the process of evaluating REHAB applications.

Communicating key funding information. According to federal standards for internal control and a leading practice related to discretionary financial assistance, agencies should communicate information important to potential applicants. Federal standards for internal control state that management should externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[32] Furthermore, these standards state that management should select appropriate methods to communicate externally. In addition, we have identified a leading practice that specifies that agencies should communicate with potential applicants prior to the application process for discretionary financial assistance awards.[33] According to the leading practice, federal agencies should provide information prior to making award decisions on key dates, funding priorities, preapplication assistance, technical review processes, eligibility, selection criteria, available funding, and types of projects to be funded, and agencies should conduct outreach to new applicants.[34] By doing so, agencies can help applicants refine their applications and ensure projects meet program requirements.

NRCS communicated some of this information to project sponsors about REHAB. For example, the March 2024 National Bulletin included information about a key date (the end of the application period), selection criteria, funding priorities, and a point of contact for preapplication assistance. The bulletin stated that NRCS would prioritize projects ready for construction first, followed by projects ready for design, and then new plans for REHAB projects. The bulletin also stated that funding for new plans would be prioritized based on whether the applicant was a new sponsor, as well as on risk, racial justice and program equity, and the ability of states to complete existing projects on time. In addition, the bulletin referenced relevant REHAB application processes in the National Watershed Program Manual, including the technical review, noting that all projects would be evaluated based on their risk index.

However, NRCS did not fully or consistently communicate other key funding information about REHAB to potential applicants in fiscal year 2024. For example, the March 2024 National Bulletin did not include information related to available funding (such as cost share requirements), eligibility, or types of projects to be funded. In addition, NRCS did not send the bulletin to all potential applicants. NRCS officials told us that its state offices are responsible for using information in the bulletin in their outreach to project sponsors. NRCS state officials said that NRCS state offices conduct outreach about REHAB through informal communication with sponsors during dam inspections, meetings on dam projects, or other events where NRCS state program managers speak with groups of sponsors. NRCS officials also told us that they present information related to REHAB at conferences for various organizations, such as the United States Society on Dams.

In addition, representatives of project sponsors for eight of the 25 dams we selected told us they were either unaware of REHAB or unclear about the requirements for receiving REHAB funding. Specifically, representatives of sponsors for one of the 25 dams we selected told us they were unaware of REHAB. Further, representatives of sponsors for seven of the dams we selected said they were unclear on the key requirements of the program. For example, one representative said they were unaware of the cost share component of REHAB. Representatives of another sponsor said that they knew about REHAB and that REHAB required a cost share but did not know anything more about the program.

NRCS has not developed a mechanism to ensure it fully and consistently communicates relevant information about REHAB funding opportunities to project sponsors. Officials at NRCS headquarters said they rely on NRCS state offices to communicate this information, because the state offices are best positioned to answer questions about the program’s requirements. However, NRCS headquarters has not clearly defined what information the state offices should communicate to sponsors about REHAB funding opportunities beyond what is in the national bulletin, or how they should communicate that information.

Without a mechanism, such as an outreach strategy, to fully and consistently communicate key information about REHAB, NRCS cannot ensure project sponsors are fully informed of funding opportunities, and the sponsors may miss opportunities to address safety risks. In creating a mechanism, NRCS could target communications to those dams most at risk (e.g., high-hazard dams and dams in the poorest condition) as part of an approach that aligns with agency priorities, as appropriate. Such an approach would also support the general process of identifying dams with the most risk in their portfolio. Moreover, without communicating complete information about the program—including information related to available funding (e.g., cost share requirements), eligibility, and types of projects to be funded—sponsors may not have the information they need to decide whether to apply for REHAB funding.

Evaluating REHAB applications. Federal standards for internal control state that agencies should internally communicate necessary quality information to achieve a program’s objectives and maintain documentation of their internal control system.[35] This documentation is evidence that controls are identified, capable of being communicated to those responsible for their performance, and capable of being monitored and evaluated by the entity. Documenting key decisions ensures that the evaluation process can be overseen by NRCS, Congress, and the public.

NRCS developed some documentation of its process for evaluating fiscal year 2024 REHAB applications. We reviewed documentation that NRCS developed of award recipients and the phase of REHAB for which the applicants sought funding. NRCS also documented the outcomes of its final funding decisions, including the amount awarded.[36]

However, NRCS did not document the rationale for its decisions during the evaluation process of the fiscal year 2024 REHAB awards. Specifically, we found that NRCS did not document how its state offices determined whether to advance fiscal year 2024 REHAB applications to headquarters. For fiscal year 2024, NRCS officials told us they awarded funding to all project applications received by NRCS headquarters. However, we found that NRCS state offices forwarded some REHAB applications to NRCS headquarters for award consideration but not others. Officials from two NRCS state offices we met with told us they could only support a limited number of projects. NRCS headquarter officials said state offices prioritize projects. However, NRCS was not able to provide documentation as to why some projects merited advancement to NRCS headquarters and others did not.

NRCS’s policy and guidance do not require NRCS to document the rationale for key decisions, such as why state offices advanced some REHAB applications, and not others, to NRCS headquarters for award consideration. As previously discussed, the March 2024 National Bulletin identified the funding priorities for the fiscal year 2024 REHAB awards. NRCS officials said that the state offices work with state and local officials to prioritize projects for funding. They also said that the specific rationale for prioritizing some projects over others can vary by state. However, without documentation of state offices’ rationale for advancing some projects over others, NRCS cannot ensure that its state offices evaluate similarly situated projects in a consistent manner. Further, NRCS cannot ensure that their decisions are transparent and align with NRCS priorities, congressional intent, and program goals to extend the evaluated life of the dam and to meet safety requirements.

NRCS officials also told us they provide training to the NRCS state offices on their responsibilities related to REHAB to ensure the offices conduct the award process consistently. We reviewed NRCS training materials and found that while the training includes information about the risk index, it does not direct the offices to document the rationale for decisions and the factors affecting the decision to forward applications to NRCS headquarters. For example, such factors could include those that may affect NRCS’s ability to meet its priorities in a state or district, such as limited NRCS state office staff resources or limited access to the private land on which the dam was constructed.

NRCS officials told us that they may be unable to fund as many dam rehabilitation projects in future years, and that the process may become more competitive. By fully documenting the rationale for key decisions, NRCS could help ensure it selects applications for REHAB awards in a consistent and transparent manner that aligns with and advances the intent and goals of REHAB. Moreover, in doing so, NRCS would be better positioned to demonstrate the integrity of its evaluation process as the process for awarding funding becomes more competitive.

Conclusions

The nation’s nearly 12,000 watershed dams play an important role in protecting communities from flooding and serve other purposes, such as providing drinking water, wildlife habitat, and recreational opportunities. With increased downstream development, the failure of these dams as they age could pose heightened safety, economic, and environmental risks. NRCS works with project sponsors through its state and district offices to support the safety of these dams. However, without taking steps to improve the overall management of the program by consistently implementing its dam safety responsibilities, NRCS cannot effectively execute its role in ensuring the continued safety of the dams. Moreover, as demands for rehabilitation assistance outpace available funding, it is important that NRCS ensure its processes for awarding REHAB funding to dam projects are transparent and clearly documented. By doing so, NRCS can help ensure that sponsors have the information they need to apply for funding, that it treats all applicants consistently, and that the public and Congress better understand how its funding decisions are advancing the program’s goals and improving the overall safety of the nation’s watershed dams.

Recommendations

We are making the following four recommendations to NRCS:

· The Administrator of NRCS should develop mechanisms to consistently implement NRCS’s policies and procedures for monitoring project sponsors’ compliance with operation and maintenance requirements for watershed dams. These mechanisms should provide direction for (1) reviewing operation and maintenance agreements made between NRCS and sponsors; (2) monitoring formal dam inspections; and (3) investigating sponsors’ potential violations of operation and maintenance requirements. (Recommendation 1)

· The Administrator of NRCS should develop a quality assurance plan and guidance for state and district offices for collecting and verifying key information in NRCS’s dams database. (Recommendation 2)

· The Administrator of NRCS should develop a mechanism to communicate key information about REHAB funding opportunities to project sponsors, including information related to available funding (such as cost share requirements), eligibility, and types of projects to be funded. (Recommendation 3)

· The Administrator of NRCS should develop guidance for NRCS state offices to document the rationale for their decisions to advance applications to NRCS headquarters for funding. (Recommendation 4)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the U.S. Department of Agriculture for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix II, the U.S. Department of Agriculture concurred with our recommendations.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Secretary of Agriculture. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at vonaha@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional

Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Andrew Von Ah

Director, Physical Infrastructure

This report assesses the extent to which (1) the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) has implemented its safety responsibilities for Watershed Program dams, and (2) NRCS’s processes for funding dam projects under the Watershed Rehabilitation Program (REHAB) are transparent.

To obtain background on NRCS and its Watershed Program dams, we reviewed pertinent laws, regulations, and relevant organizations’ reports on NRCS watershed dams.[37] Specifically, we reviewed several NRCS manuals and handbooks, including its National Watershed Program Manual, National Operation and Maintenance Manual, and National Engineering Manual. We also reviewed our relevant prior reports and reports from the Congressional Research Service. In addition, we interviewed selected nongovernmental stakeholders and conducted local site visits to inform our design. Specifically, we selected three dams in California, Maryland, and Virginia located near our analysts’ offices. We conducted preliminary interviews with officials from the three NRCS state offices and four project sponsors that oversee these dams to better understand how NRCS assists sponsors and other relevant issues.

For both objectives, we reviewed NRCS’s policies and guidance related to its Watershed Programs and interviewed NRCS officials responsible for administering the programs. We selected a nongeneralizable sample of 25 dams in five states based on a range of criteria to obtain diversity in the dams selected, including geography, number of dams in the state, condition assessment, and age. We also focused our selection on high- and significant-hazard dams, as they pose the greatest potential risk to life and property.[38] We used this nongeneralizable sample to better assess how NRCS oversees its portfolio of dams. We interviewed the project sponsors for each of the 25 dams and conducted in-person site visits to 10 of the dams. For each selected state, we interviewed NRCS state office officials and state dam safety officials. The information gathered from this sample is not generalizable to all dams but provides insight into NRCS’s approach to administering its Watershed Programs. Table 2 lists the 25 dams we selected and the dams we visited.

|

State |

Dam name |

Site visit location |

|

Indiana |

Busseron Creek G-4 |

|

|

Muddy Fork 1 |

|

|

|

Muddy Fork 6 |

|

|

|

Stucker Fork 9 |

|

|

|

Twin-Rush Creek 1 |

|

|

|

Mississippi |

Abiaca Creek Structure Y-34-8 |

ü |

|

Big Sand Creek Structure Y-32-11 |

ü |

|

|

Buntyn Creek Structure Y-16A-1 |

ü |

|

|

Buntyn Creek Structure Y-16A-4 |

ü |

|

|

Town Creek Watershed Structure 39 |

|

|

|

New Mexico |

Caballo Arroyo Site 4 |

|

|

Hatch Valley Arroyo Site 2 |

|

|

|

Sebastian Martin-Black Mesa Site 5 |

|

|

|

T or C– Williamsburg Site 8C |

|

|

|

Tortugas Site 1 |

|

|

|

Texas |

East Fork Above Lavon Watershed NRCS Site 3B |

ü |

|

Pilot Grove Creek Watershed NRCS Site 29 |

ü |

|

|

Upper Bosque River Watershed NRCS Site 2 |

|

|

|

Upper East Fork Laterals Watershed NRCS Site 4B |

ü |

|

|

Upper East Fork Laterals Watershed NRCS Site 5B |

ü |

|

|

West Virginia |

Brush Creek 15 |

|

|

New Creek 1 |

ü |

|

|

North and South Mill Creek 3 |

|

|

|

Patterson Creek 3 |

|

|

|

Patterson Creek 22 |

ü |

Legend: ü = GAO conducted in-person site visit

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107404

To assess the extent to which NRCS has implemented its safety responsibilities for dams built under its Watershed Programs, we evaluated NRCS’s adherence to its own policies for monitoring project sponsors’ operation and maintenance activities. We reviewed NRCS’s operation and maintenance policies, including those related to communicating, documenting, and enforcing the agency’s operation and maintenance requirements. We collected and reviewed a variety of documents from the administrative files of the 25 selected dams. Specifically, we reviewed all available operation and maintenance agreements, inspection reports, and dam assessment reports, among other documents, for fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023. We compared the contents of the documentation with requirements in NRCS’s policies, and we compared the information included in the documents with what NRCS’s policies state should be included in the documents. In addition, we evaluated the extent to which NRCS’s approach aligned with Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government—specifically, the principles that management should develop and maintain documentation of its internal control system, and that agencies should identify deficiencies through monitoring activities and determine appropriate corrective actions to remedy these deficiencies.[39]

To understand what data NRCS collects and maintains on its dams and to evaluate the extent to which NRCS uses data to manage the dams’ safety, we reviewed NRCS’s policies related to data collection. We also analyzed the agency’s dam inventory database, called GeoObserver, current as of August 1, 2024. We reviewed the data to understand what variables NRCS collects that relate to dam safety, including hazard classification, date of last inspection, and evaluated life. We also reviewed other data on the dams’ characteristics, including location, year built, and ownership. We analyzed the data for completeness and accuracy and interviewed NRCS officials about the reliability of the data. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable for our purposes. We compared the findings from our analyses with NRCS’s policies to assess whether NRCS had implemented its policies and procedures, as well as with federal standards for internal control—specifically, the principles that management should obtain relevant data from reliable sources and process data into quality information.[40]

To assess the extent to which NRCS’s processes for funding REHAB projects are transparent, we reviewed data on REHAB projects awarded in fiscal year 2024. We compared this information with NRCS’s policies and procedures for communicating funding availability and evaluating applications that were in place during fiscal year 2024, and with federal standards for internal control and a leading practice. For federal standards for internal control, we compared NRCS’ processes with the principles that management should externally and internally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives, and that management should develop and maintain documentation of its internal control system.[41] In addition, we compared NRCS’s processes with a leading practice on communicating information with potential applicants prior to the application process.[42]

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Andrew Von Ah, vonaha@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Matt Voit (Assistant Director), Michelle Everett (Analyst in Charge), Melanie Diemel, Nick Graves, Geoffrey Hamilton, Alicia Loucks, Joshua Parr, Matt Rowen, Laurel Voloder, and Elizabeth Wood made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]The evaluated life is the intended period that NRCS estimates a dam will function successfully with only routine maintenance. NRCS uses the evaluated life to determine the duration of operation and maintenance agreements between NRCS and project sponsors. Dams are expected to provide enough economic benefits over their evaluated life to justify their original cost plus routine maintenance costs. The end of the evaluated life does not signal the expiration of a dam’s functionality or viability. According to NRCS, the evaluated life is typically 50 years.

[2]NRCS Watershed Programs, including the Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Operations and Watershed Rehabilitation Program, provide technical and financial assistance to local government agencies, tribal organizations, and other eligible sponsors, to help communities implement conservation practices that address watershed resource concerns.

[3]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014).

[6]The leading practice on communication is one of several leading practices we identified that are used across the federal government to ensure the fair and objective evaluation and selection of discretionary grant awards. The leading practice is based on policies and guidance used by the Office of Management and Budget and other federal agencies, and on our prior work. GAO, Intercity Passenger Rail: Recording Clearer Reasons for Awards Would Improve Otherwise Good Grantmaking Practices, GAO‑11‑283 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 10, 2011). We have also applied the leading practice on communication to our work on bridge investments. GAO, Bridge Investment Program: DOT Should Refine Processes to Improve Consistency, GAO‑25‑107227 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 11, 2024).

[7]The National Inventory of Dams is a database of all known dams in the United States and its territories that meet certain criteria. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is responsible for maintaining the database, which includes more than 70 data fields, and works closely with federal and state agencies to obtain accurate and complete information. A watershed is the land area drained by a river or stream.

[8]According to NRCS, there are 10 federally owned NRCS dams. Most of these dams are owned by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s U.S. Forest Service.

[9]Flood Control Act of 1944, Pub. L. No. 78-534, 58 Stat. 887.

[10]The Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Act established a permanent nationwide program that authorized the federal government to cooperate with states and their political subdivisions to conserve, develop, utilize, and dispose of water to preserve and protect land and water resources. Pub. L. No. 83-566, 68 Stat. 666. The Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Act, as amended, authorizes the provision of financial and other assistance to local watershed sponsors whereby the local watershed sponsors are responsible for initiating, implementing, sharing in costs, and operating and maintaining the watershed projects.

[11]Routine maintenance includes mowing the dam, removing any trees, repairing any holes or tracks caused by animals, and keeping the intake tower clear of debris. For dams on private property, sponsors must have access rights such as easements to access the dam for operations and maintenance.

[12]Each state has an NRCS state office led by a state conservationist, as well as district NRCS offices.

[13]Grain Standards and Warehouse Improvement Act of 2000, Pub. L. No. 106-472, § 313, 114 Stat. 2058, 2077 (codified, as amended at 16 U.S.C. § 1012). This legislation, known as the Small Watershed Rehabilitation Amendments of 2000, amended the Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Act and authorized, among other things, the provision of financial and technical assistance to help rehabilitate aging watershed dams. Dams that are near, at, or past the end of their evaluated life are eligible to apply for REHAB.

[14]The Watershed Rehabilitation Program is currently authorized to be appropriated $85 million per fiscal year until September 30, 2025. See 16 U.S.C. § 1012(h)(2)(E), as extended by the American Relief Act, 2025 (Pub. L. No. 118-158, § 4101, 138 Stat. 1722, 1767 (2024)). The permanent appropriation, enacted by the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, provided $50 million “for fiscal year 2019 and each fiscal year thereafter” for Small Watershed Rehabilitation Program and Watershed and Flood Prevention Operations Program activities. Pub. L. No. 115-334, § 2401,132 Stat. 4490, 4570 (2018). In addition, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, enacted in 2021, appropriated $118 million for the Watershed Rehabilitation Program, to remain available until expended. Pub. L. No. 117-58, div. J, tit. I, 135 Stat. 429, 1351 (2021).

[15]The statutorily specified U.S. Department of Agriculture water resource programs dams eligible for REHAB assistance are set out at 16 U.S.C. § 1012(a)(2). Dams outside of the evaluated life are still eligible to apply for REHAB. If the dam is awarded REHAB, NRCS and the project sponsor would begin a new contractual agreement and new evaluated life of the dam.

[16]The NRCS state office may coordinate with an architectural or engineering firm, or other qualified entity, to conduct the REHAB assessment of the dam, which NRCS staff must approve.

[17]Decommissioning a dam involves taking a dam out of service in a safe and environmentally sound manner or converting it to another purpose. NRCS may decommission a dam in some cases, such as at the request of the project sponsor. NRCS officials identified two dams that have been decommissioned. NRCS officials said that decommissioning is rarely the best option, as the dams continue to provide benefits and rehabilitating a dam is a more cost-effective alternative.

[18]State dam safety programs typically include safety evaluations of existing dams, review of plans for dam construction and major repair work, periodic inspections of dams, and emergency preparedness activities. According to NRCS, every state (except Alabama) has established a regulatory program for dam safety.

[19]NRCS’s policy recognizes four types of inspections: (1) monitoring inspections are informal, routine visual assessments of a dam that can be conducted by anyone; (2) special inspections should be conducted immediately after a major weather or other event (e.g., floods, earthquakes, or vandalism) that could affect the dam structure; (3) annual inspections are conducted on all dams regardless of hazard classification, to ensure they are functioning as designed; and (4) formal inspections are conducted at least once every 5 years for significant- and high-hazard dams under the leadership of a qualified engineer. States also have dam safety laws and regulations requiring dams to be inspected at varying intervals depending on their hazard classification.

[20]NRCS has three primary manuals that set out the policies for managing Watershed Program dams: (1) National Watershed Program Manual; (2) National Operation and Maintenance Manual; and (3) National Engineering Manual.

[21]According to NRCS’s policy, these inspections are to be performed by a qualified engineer. Formal inspections may be conducted by NRCS staff or other qualified engineers from outside NRCS.

[22]One of the 25 dams we selected was classified as low hazard, which does not need to be formally inspected every 5 years, according to NRCS’s policy.

[23]These 473 dams do not include dams for which NRCS data on date of last inspection are missing or contain anomalous values. We discuss missing and anomalous values in NRCS’s dam data below.

[24]NRCS, National Operation and Maintenance Manual.

[25]U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Title 210, National Engineering Manual, 4th edition (June 2017).

[27]The four values, in descending order of condition, are satisfactory, fair, poor, and unsatisfactory. There are also “Not Rated” values.

[28]Two states—Kansas and Oklahoma—had anomalous values. For Kansas, nearly all of its 834 NRCS dams had 1/1/1970 listed as the date of last inspection, and for Oklahoma, nearly all of its 2,107 NRCS dams had 12/31/2011 listed as the date of last inspection.

[29]According to our analysis of NRCS data, most NRCS Watershed Program dams were built with a 50-year evaluated life, but some were built with a 100-year evaluated life.

[30]The most recent bulletin for REHAB funding was published on the U.S. Department of Agriculture website in March 2025.

[31]REHAB is subject to Executive Order 12372, Intergovernmental Review of Federal Programs, according to NRCS officials. See also, 7 C.F.R. § 622.7. Executive Order No. 12372 was issued to foster intergovernmental partnership and strengthen federalism by relying on state and local processes for the state and local coordination and review of proposed federal financial assistance and direct federal development. The executive order requires intergovernmental consultation and that federal agencies use state processes to determine official state and local views, among other things, to the extent permitted by law. 47 Fed. Reg. 30959 (July 14, 1982).

[36]According to NRCS officials, all fiscal year 2024 REHAB awards were signed as of September 30, 2024. Officials said NRCS is reviewing the extent to which its grant programs are subject to the requirements of executive orders.

[37]NRCS’s Watershed Programs include the Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Operations program, Emergency Watershed Protection Program, and REHAB.

[38]We selected 22 high-hazard dams, two significant-hazard dams, and one low-hazard dam.

[39]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014).

[42]The leading practice on communication is one of several leading practices we identified that are used across the federal government to ensure the fair and objective evaluation and selection of discretionary grant awards. The leading practices are based on policies and guidance used by the Office of Management and Budget and other federal agencies, and on our prior work. GAO, Intercity Passenger Rail: Recording Clearer Reasons for Awards Would Improve Otherwise Good Grantmaking Practices, GAO‑11‑283 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 10, 2011). We have also applied the leading practice on communication to our work on bridge investments. GAO, Bridge Investment Program: DOT Should Refine Process to Improve Consistency, GAO‑25‑107227 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 11, 2024).