HIGH-RISK SERIES

Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107743. For more information, contact Michelle Sager at (202) 512-6806 or SagerM@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107743, a report to congressional committees

Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness

Why GAO Did This Study

The federal government is one of the world’s largest and most complex entities. About $6.8 trillion in outlays in fiscal year 2024 funded a broad array of programs and operations. GAO’s High-Risk Series identifies government operations with serious vulnerabilities to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement, or in need of transformation.

This biennial update describes the status of high-risk areas, outlines actions that are needed to assure further progress, and identifies a new high-risk area needing attention by the executive branch and Congress.

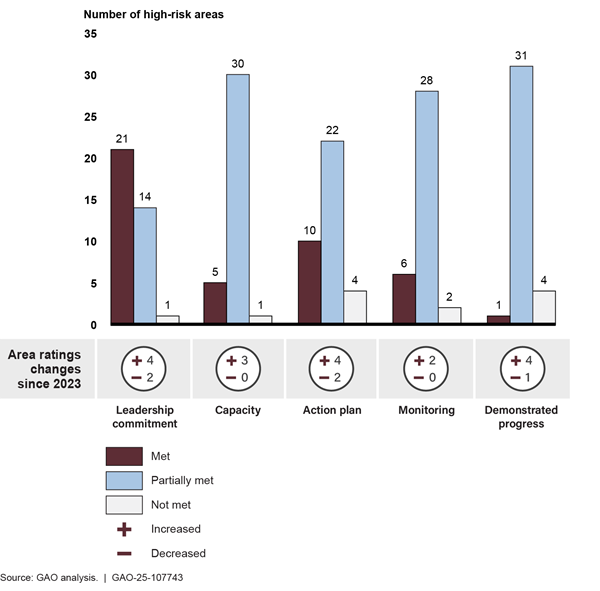

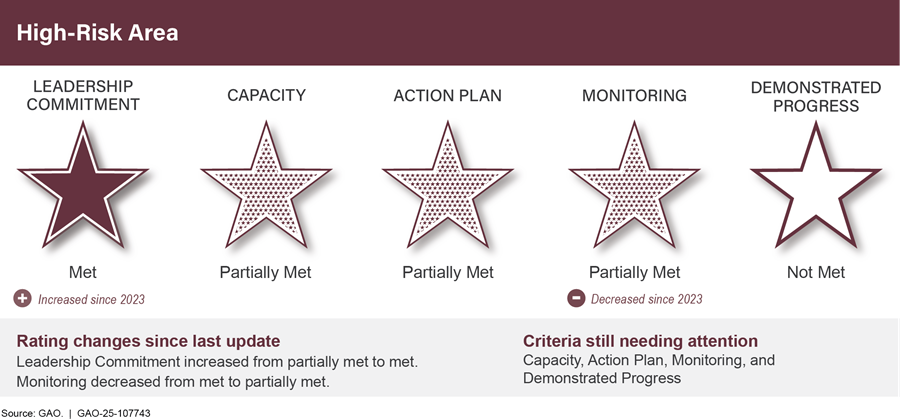

GAO uses five criteria to assess progress in addressing high-risk areas: (1) leadership commitment; (2) agency capacity; (3) an action plan; (4) monitoring efforts; and (5) demonstrated progress. Ratings are based on analysis of actions taken up to the end of the 118th Congress.

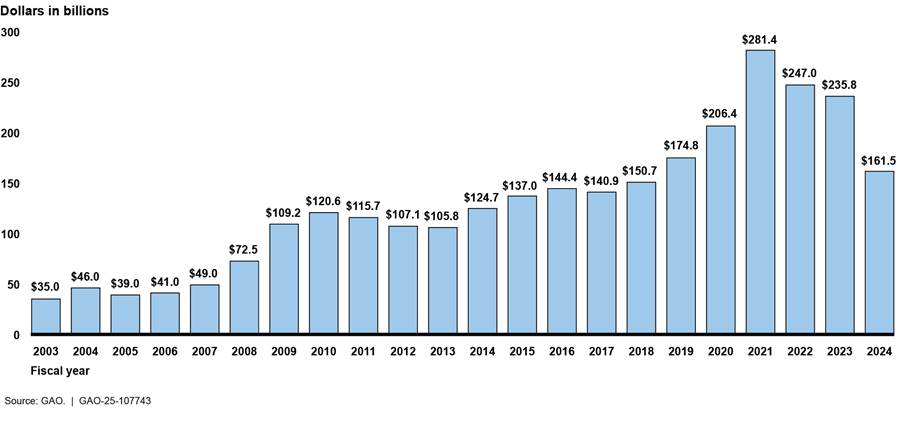

Efforts to address high-risk issues have contributed to hundreds of billions of dollars saved. Over the past 19 years (fiscal years 2006-2024), these financial benefits totaled nearly $759 billion or an average of $40 billion per year.

What GAO Recommends

Executive branch agencies need to address thousands of open GAO recommendations to bring about lasting solutions to the 38 high-risk areas.

Continued congressional oversight is essential to achieve greater progress and legislation is needed in some cases. Congress also should consider requiring that interagency groups formed to address these challenges use leading practices for collaboration.

What GAO Found

Since GAO’s 2023 update to the High-Risk List, Congress and executive branch agencies have taken actions resulting in notable improvements across the 37 high-risk areas. These efforts over the last two years resulted in about $84 billion in financial benefits. However, the progress made overall varied. Ten areas improved and three regressed, while the others maintained their position, were rated for the first time, or were newly added, as shown on page 5. Lasting solutions to high-risk problems save billions of dollars, improve service to the public, and increase government performance and accountability.

New Area: Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistance

Natural disasters have become costlier and more frequent. In 2024, there were 27 disasters with at least $1 billion in economic damages. Overall, these events resulted in 568 deaths and significant economic effects on the affected areas. Their frequency and intensity have severely strained the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and its workforce.

Recent natural disasters—including wildfires in Southern California and hurricanes in the Southeast—demonstrate the need for federal agencies to deliver assistance as efficiently and effectively as possible and reduce their fiscal exposure.

The federal approach to disaster recovery is fragmented across over 30 federal entities. So many entities involved with multiple programs and authorities, differing requirements and timeframes, and limited data sharing across entities could make it harder for survivors and communities to navigate federal programs.

FEMA and other federal entities—including Congress—need to address the nation’s fragmented federal approach to disaster recovery. Attention is also needed to improve processes for assisting survivors, invest in resilience, and strengthen FEMA’s disaster workforce and capacity.

Several Areas Critical to Better Managing the Cost of Government

|

|

Reducing Billions in Significant Improper Payments and Fraud |

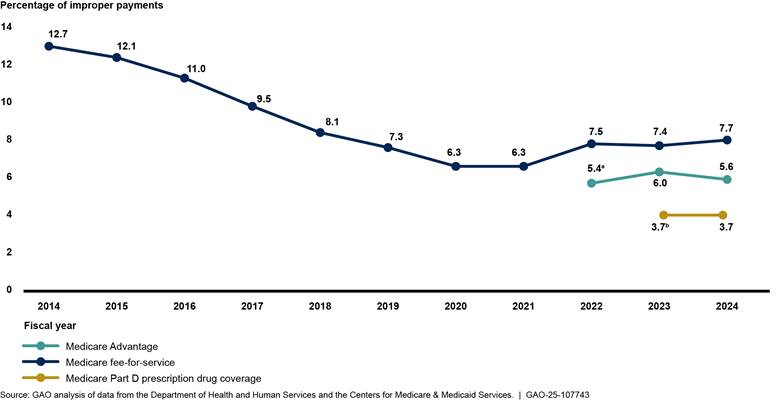

Since 2003, federal agencies have reported about $2.8 trillion in estimated improper payments, including over $150 billion government-wide in each of the last 7 years. These figures do not represent a full accounting of improper payments because agencies have not reported estimates for some programs as required. For example, we found that agencies failed to report fiscal year 2023 improper payment estimates for nine risk-susceptible programs.

The areas on the High-Risk List include programs that represented about 80 percent of the total government-wide reported improper payment estimate. These include two of the fastest-growing programs—Medicare and Medicaid—as well as the unemployment insurance system and the Earned Income Tax Credit. While agencies and the Department of the Treasury are taking some steps to address this issue, much more needs to be done to control billions of dollars in overpayments and prevent fraud. Implementation of GAO’s recommendations by agencies and the Congress would help achieve better program integrity.

|

|

Closing Large Gaps in Revenue Owed to the Government |

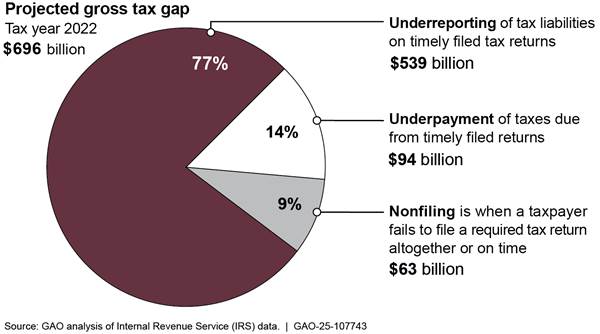

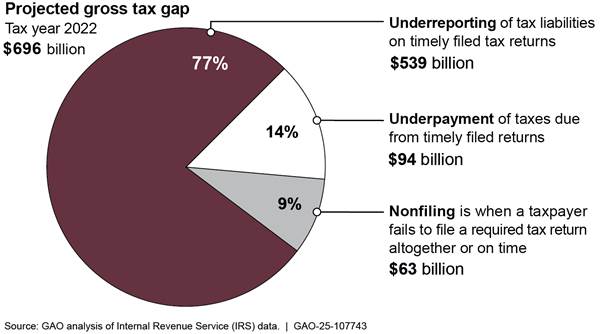

In 2024, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) projected that the gross tax gap—the difference between taxes owed and taxes paid on time—was $696 billion for tax year 2022. IRS estimated that it will collect an additional $90 billion through late payments and enforcement actions, leaving an estimated $606 billion net tax gap. Also, IRS is continually addressing billions of dollars of attempted tax fraud through identity theft. Further, the Department of the Interior does not have reasonable assurance that it is collecting the entirety of the billions owed on oil and gas leases on federal lands. Actions by federal agencies and Congress on related GAO recommendations can help significantly to close these gaps and improve the government’s fiscal position.

|

|

Better Controlling Cost Growth and Schedule Delays in High Dollar Value Procurements |

The government has great difficulty in controlling the costs of major acquisitions in its more than $750 billion procurement portfolio. This includes procurements critical to national defense, nuclear weapon systems modernization and clean up, space programs, and health care to veterans. Many major acquisitions by agencies such as the Department of Defense (DOD), the Department of Energy, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) have experienced cost growth, schedule delays, or both. Implementation of GAO’s recommendations, which include more consistently applying leading practices, could yield billions in savings and provide more timely delivery.

|

|

Rightsizing the Government’s Property Holdings Could Generate Substantial Savings |

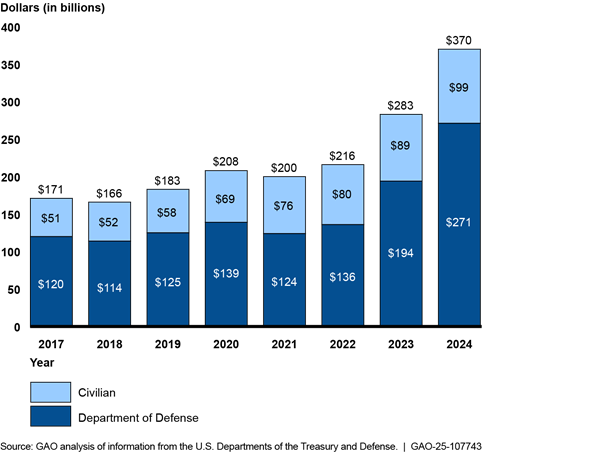

The federal government is one of the nation’s largest property holders. Annual maintenance and operating costs for its 277,000 buildings exceeded $10.3 billion in fiscal year 2023. Managing real property was designated high risk in 2003 because of large amounts of underused property and the great difficulty in disposing of unneeded holdings and ensuring the safety of workers and visitors. Costliness and underuse of government property holdings have been exacerbated by the recent use of telework and growing amounts of deferred maintenance, which rose from $170 billion in 2017 to $370 billion in 2024.

GAO recommended more appropriate utilization benchmarks be established to guide better and more timely property management. Also, lessons need to be applied from recent failed attempts to expedite disposals to establish a more viable process. Efforts are also needed to better manage and maintain property.

|

|

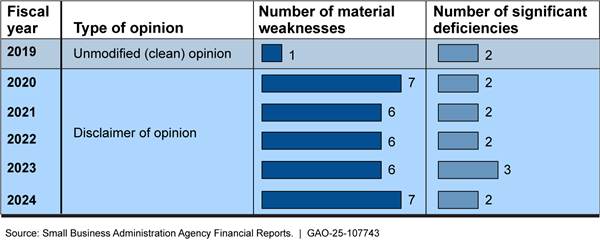

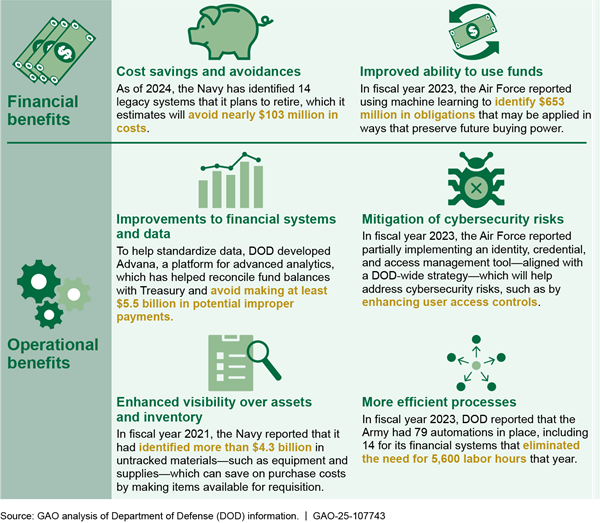

Achieving Greater Financial Management Discipline at DOD |

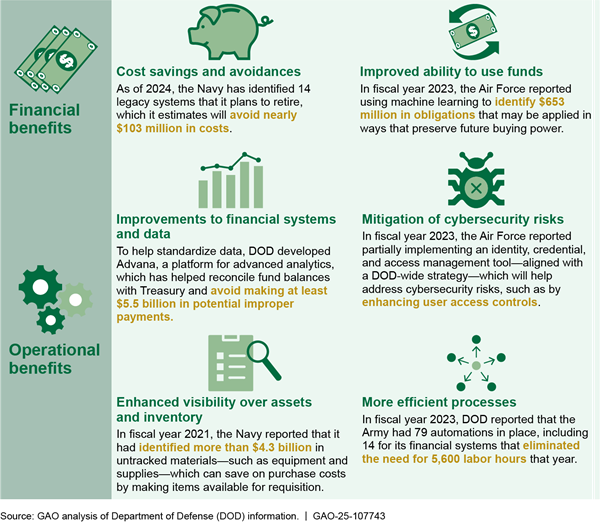

DOD is the only major federal agency to have never achieved an unmodified “clean” opinion on its financial statements. The department is committed to the goal of achieving a clean opinion on its statements and has made important progress in reaping several financial and operational benefits. A clean opinion was recently obtained by the Marine Corps, in addition to several smaller components. DOD needs to redouble its efforts to revamp financial management systems, more promptly fix problems identified by its auditors, and focus more on ensuring a well-qualified workforce to attain proper accountability and potential savings.

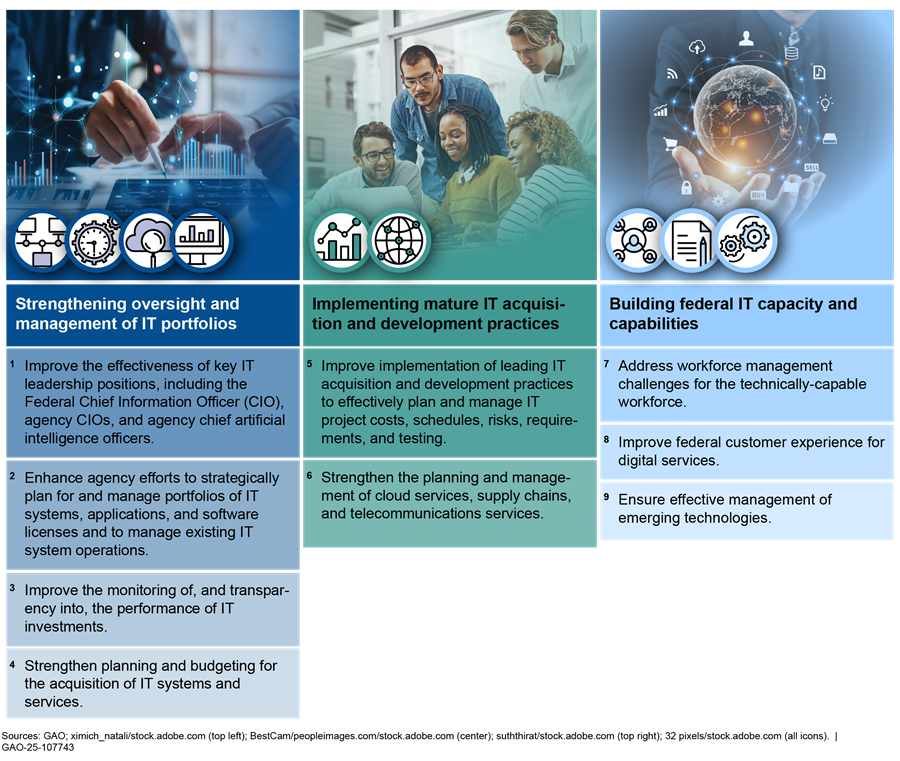

Harnessing Modern Information Technology to Improve Services and Programs

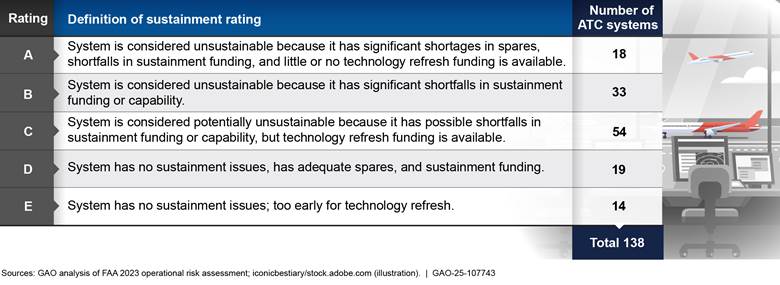

The federal government spends more than $100 billion annually on IT, with the vast majority of this spent on operations and maintenance of existing systems rather than new technology. Currently, the government, in many cases, is carrying out critical missions with decades-old legacy technology that also carries tremendous security vulnerabilities. Many attempts to implement new systems have too often run far over budget, experienced significant delays, and delivered far fewer improvements than promised. Recent challenges at the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Department of Education, and VA vividly illustrate this situation.

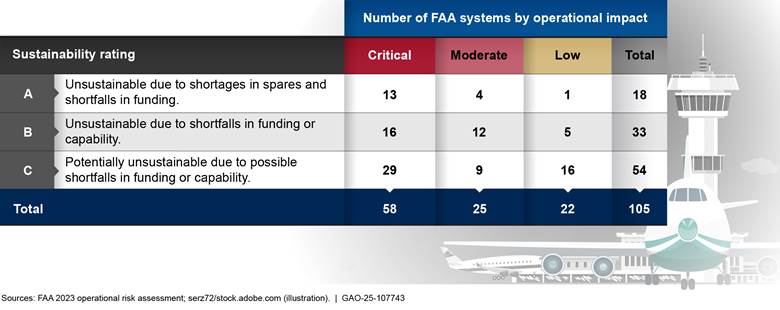

· FAA has experienced increasing challenges with aging air traffic control systems in recent years and has been slow to modernize the most critical and at-risk systems. A 2023 operational risk assessment determined that of FAA’s 138 systems, 51 (37 percent) were unsustainable with significant shortages in spare parts, shortfalls in sustainment funding, little to no technology refresh funding, or significant shortfalls in capability. An additional 54 (39 percent) were potentially unsustainable.

· The Department of Education's Office of Federal Student Aid did not adequately plan for its deployment of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) Processing System. The initial rollout of the new system was delayed several times, faced several critical technical issues, and experienced very poor customer service. This contributed to about 9 percent fewer high school seniors and other first-time applicants submitting a FAFSA, as of August 25, 2024.

· After three unsuccessful attempts between 2001 and 2018, VA initiated a fourth effort—the electronic health record (EHR) modernization program—to replace its health records system. In 2022, the Institute for Defense Analysis estimated that EHR modernization life cycle costs would total $49.8 billion—$32.7 billion for 13 years of implementation and $17.1 billion for 15 years of sustainment. VA remains in the early stages of deploying its new EHR system across 160 locations. As of December 2024, VA deployed the EHR system to just six of its locations and plans to deploy it at four more locations in 2026. There are over 160 remaining locations for EHR implementation.

These are examples of poor performance that led GAO to designate Improving IT Acquisitions and Management as a government-wide high-risk area in 2015. There have been some improvements, including closing unneeded data centers, which saved billions of dollars. Congressional oversight by the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Subcommittee on Government Operations, has helped spur improvements and included exhortations to have Chief Information Officers (CIO) more involved.

Of the 1,881 recommendations made by GAO for this high-risk area since 2010, 463 remained open as of January 2025. Agency leaders need to give this area a higher priority and provide their CIOs necessary authorities and support if the government is ever to reap the benefits of modern technology.

Expediting the Pace of Cybersecurity and Critical Infrastructure Protections

While improvements have been made and efforts continue, the government is still not operating at a pace commensurate with the evolving grave cybersecurity threats to our nation’s security, economy, and well-being. State and non-state actors are attacking our government and private-sector systems thousands of times each day. In addition to national security and intellectual property, systems supporting daily life of the American people are at risk, including safe water, ample supply of energy, reliable and secure telecommunications, and our financial services.

GAO has made 4,387 related recommendations since 2010. While 3,623 have been implemented or closed, 764 have not been fully implemented. Also, greater federal efforts are needed to better understand the status of private sector technological developments with cybersecurity implications—such as artificial intelligence— and to continue to enhance public and private sector coordination.

Seizing Opportunities to Better Protect Public Health and Reduce Risk

Several of GAO’s high-risk areas focus on addressing critical weaknesses in public health efforts. GAO’s recommendations focus on

· ensuring the Department of Health and Human Services significantly elevates its ability to provide leadership and coordination of public health emergencies;

· providing the Food and Drug Administration with a much greater capacity to (1) inspect foreign drug manufacturers that produce many of the drugs consumed by Americans and (2) take stronger actions to address persistent drug shortages, including cancer therapies;

· improving the timeliness and quality of care given to our veterans, including mental health and suicide prevention, especially in rural areas;

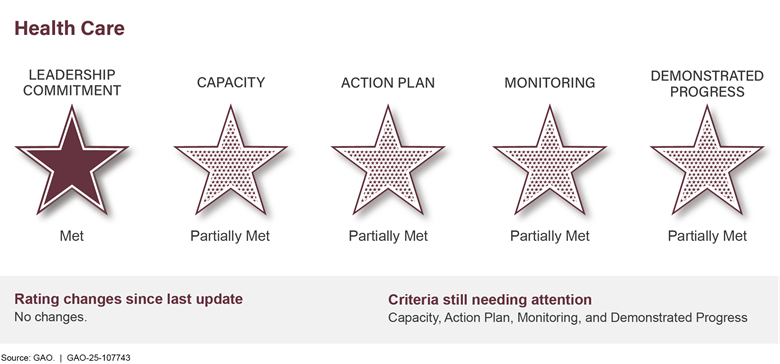

· ensuring better health care by the Indian Health Service to Tribes and their members;

· providing national leadership to prevent drug abuse and further reduce overdose deaths; and

· ensuring the Environmental Protection Agency provides more timely reviews of potentially toxic chemicals before they are introduced into commercial production and widespread public use.

There is also a need for a more comprehensive approach to food safety to address fragmentation among 15 different federal agencies and at least 30 federal laws. While the United States has one of the safest food supplies in the world, every year millions of people are sickened by foodborne illnesses, tens of thousands are hospitalized, and thousands die. A more proactive, coordinated approach that takes greater advantage of modern technology would be in the best interest of Americans and would lead to a more efficient government.

Other Concerning High-Risk Areas

|

|

Modernizing our Financial Regulatory Systems |

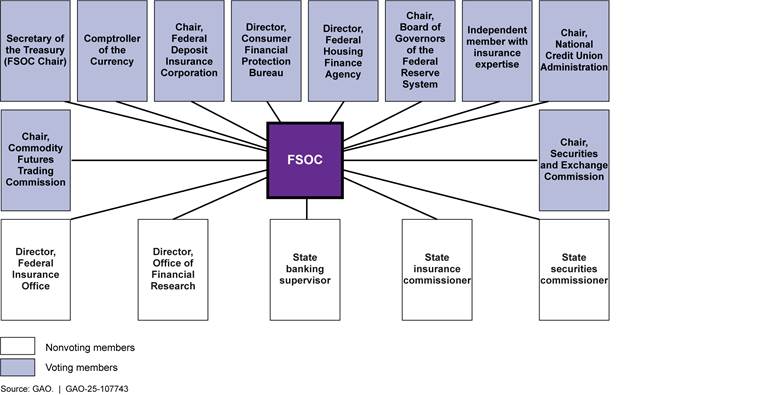

Actions are needed to strengthen oversight of financial institutions and address regulatory gaps. The March 2023 bank failures and rapid adoption of emerging technologies in the marketplace have highlighted continued challenges in the regulatory system since GAO initially designated this area as high-risk in 2009, during the financial crisis. In particular, the Federal Reserve should improve procedures so that decisions to escalate supervisory concerns happen in a timely manner and Congress should consider designating a federal regulator for certain crypto asset markets, as we recommended.

|

|

Resolving the Federal Role in Housing Finance |

There is an essential need for Congress to clarify the federal role for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two private sector entities that provide underwriting for the U.S. mortgage market. They are still in federal conservatorship from the 2008 global financial crisis with no clear path forward. The other key federal players, Ginnie Mae and the Federal Housing Administration, have had their portfolios greatly expanded to $2.6 trillion and $1.4 trillion respectively. Consequently, the federal government is greatly exposed to a downturn in the housing market.

|

|

Addressing Long-Standing Issues with the Bureau of Prisons |

Prison buildings are deteriorating and in need of repair and maintenance, while facilities are understaffed, putting both incarcerated people and staff at risk. Moreover, efforts to prevent recidivism have not been thoroughly evaluated, undermining a key goal to help incarcerated people make a successful transition into society once released. The Bureau of Prisons has made some progress, but much more needs to be done.

|

|

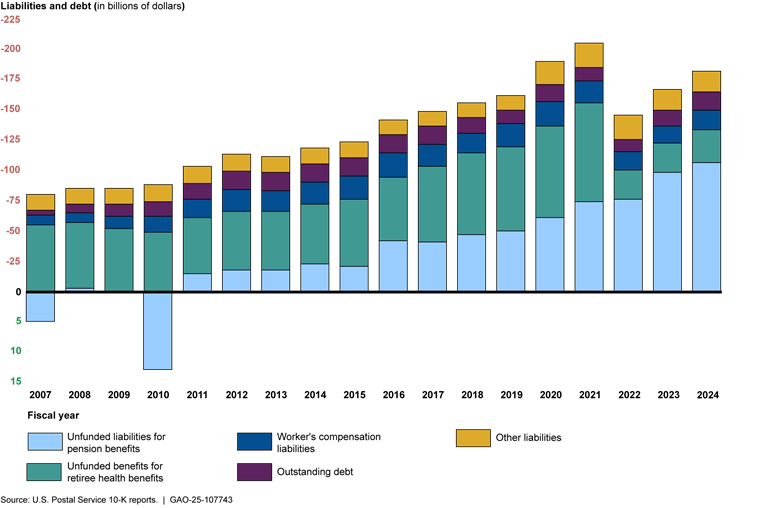

Fixing the United States Postal Service’s (USPS) Outdated Business Model |

Congress acted to alleviate certain fiscal pressures and USPS is trying to reduce costs, but it is still losing money ($16 billion in fiscal years 2023 and 2024) and has extensive liabilities and debt ($181 billion in fiscal year 2024). USPS estimates that the fund supporting postal retiree benefits will be depleted in fiscal year 2031. At that point, USPS would be required to pay its share of retiree health care premiums, which USPS projects to be about $6 billion per year. There is a fundamental tension between the level of service Congress expects and what revenue USPS can reasonably be expected to generate. Congress needs to establish what services it wants USPS to provide and negotiate a balanced funding arrangement.

|

|

Addressing the Government’s Human Capital Challenges |

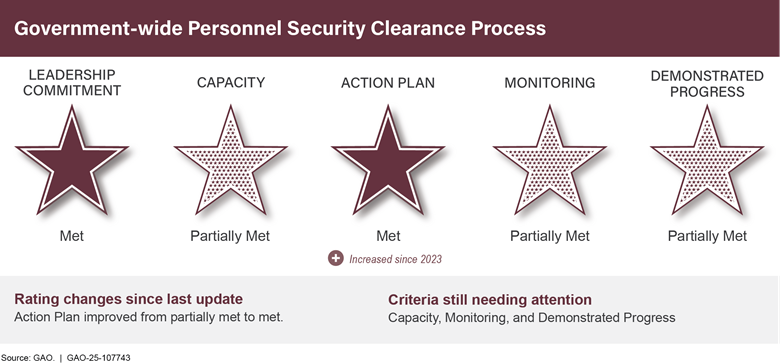

Twenty areas are on GAO’s High-Risk List in part due to skills gaps or an inadequate number of staff. Moreover, the personnel security clearance system is not yet being managed in the best manner to ensure that people are adequately screened to handle sensitive information.

Icon sources: GAO, USPS, and Icons-Studio/stock.adobe.com.

GAO’s 2025 High-Risk List, Changes Since 2023

|

High-risk area |

Change since 2023 |

|

Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistancea,b (area not rated because it is newly added) |

n/a |

|

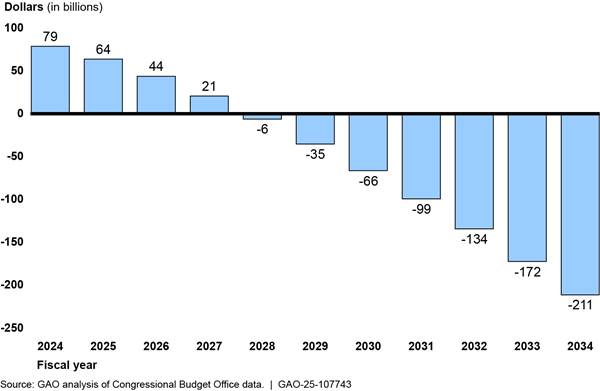

Funding the Nation’s Surface Transportation Systema (area not rated because it primarily involves congressional action) |

n/a |

|

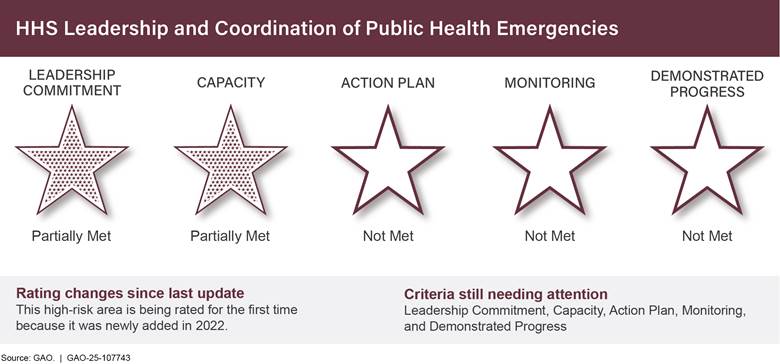

HHS Leadership and Coordination of Public Health Emergenciesb (area rated for the first time) |

n/a |

|

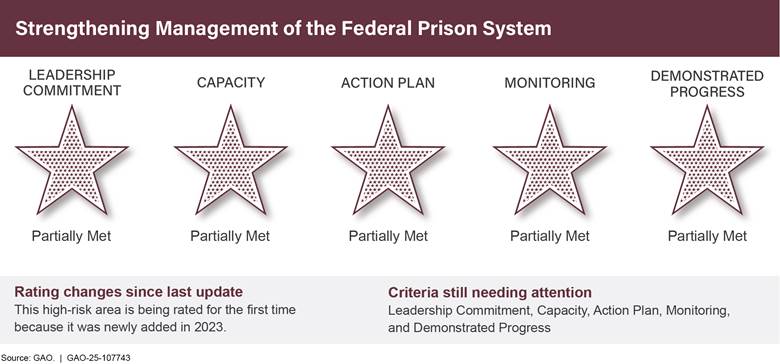

Strengthening Management of the Federal Prison System (area rated for the first time) |

n/a |

|

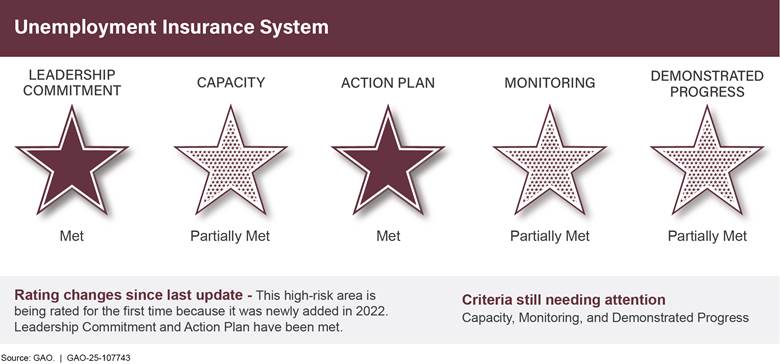

Unemployment Insurance Systema,b (area rated for the first time) |

n/a |

|

DOD Approach to Business Transformation |

↑ |

|

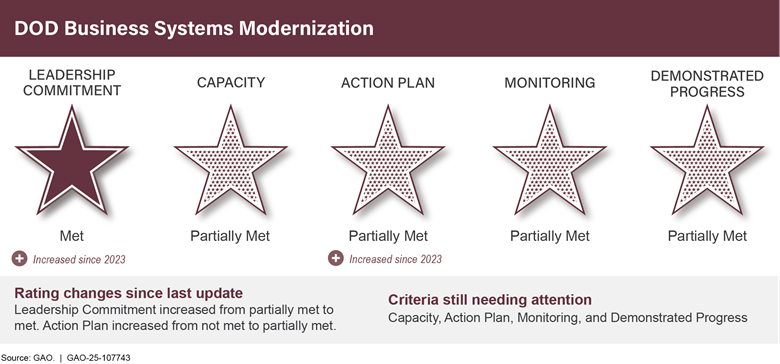

DOD Business Systems Modernization |

↑ |

|

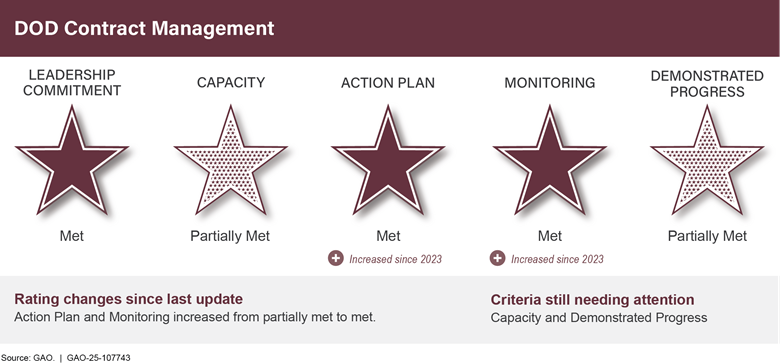

DOD Contract Management |

↑ |

|

Emergency Loans for Small Businesses |

↑ |

|

Government-wide Personnel Security Clearance Processa,b |

↑ |

|

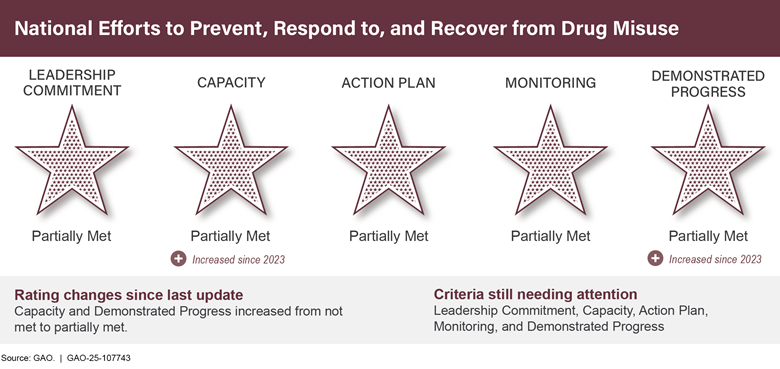

National Efforts to Prevent, Respond to, and Recover from Drug Misuseb |

↑ |

|

National Flood Insurance Programa |

↑ |

|

Resolving the Federal Role in Housing Financea,b |

↑ |

|

U.S. Government’s Environmental Liabilitya,b |

↑ |

|

USPS Financial Viabilitya |

↑ |

|

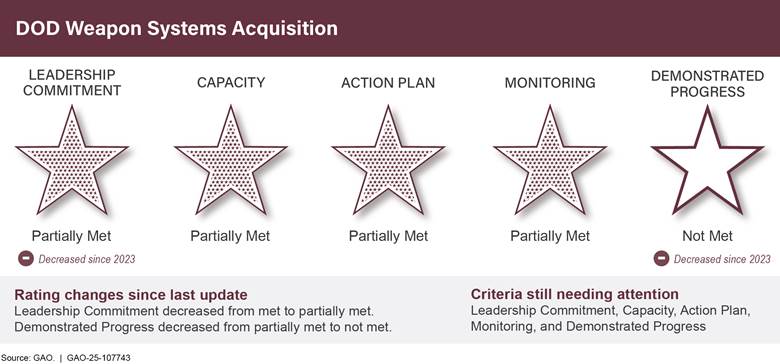

DOD Weapon Systems Acquisitiona |

↓ |

|

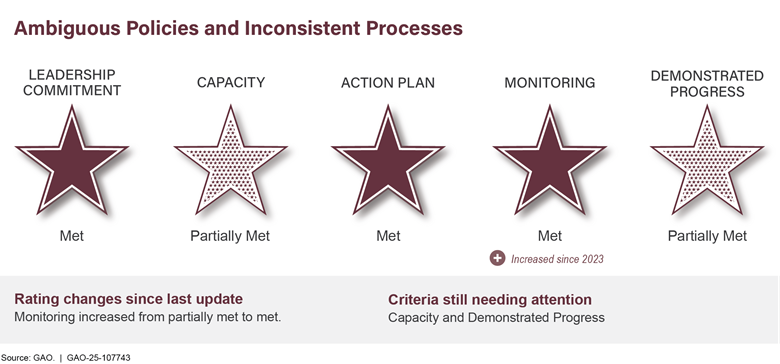

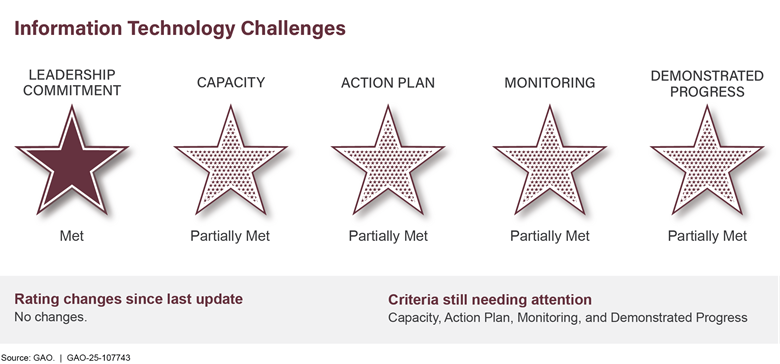

Improving IT Acquisitions and Managementa,b |

↓ |

|

Managing Federal Real Propertyb |

↓ |

|

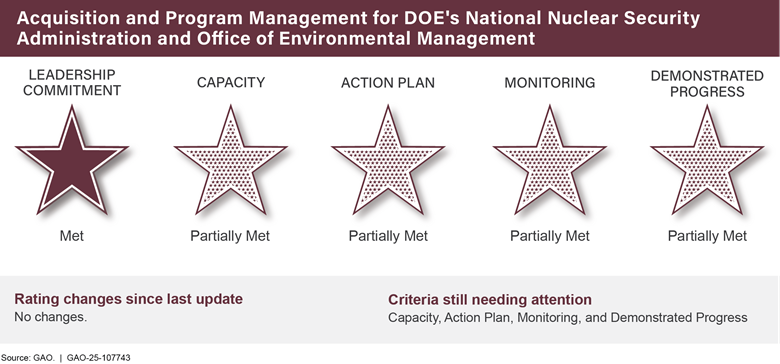

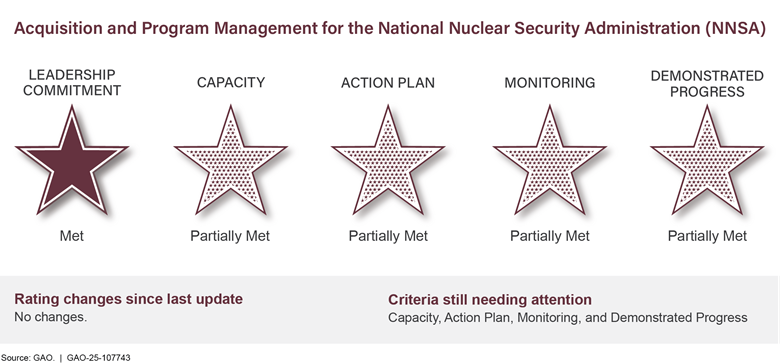

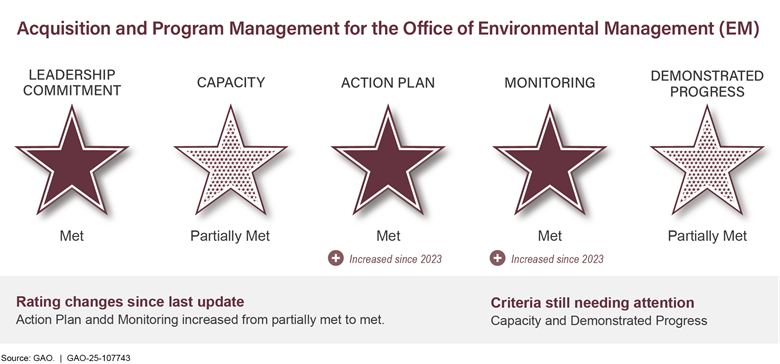

Acquisition and Program Management for DOE’s National Nuclear Security Administration and Office of Environmental Managementa |

● |

|

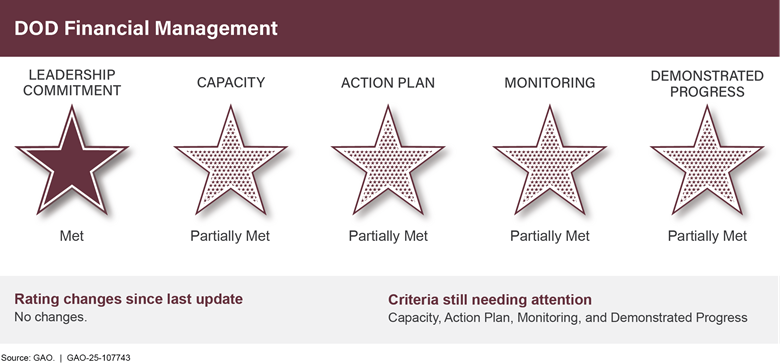

DOD Financial Management |

● |

|

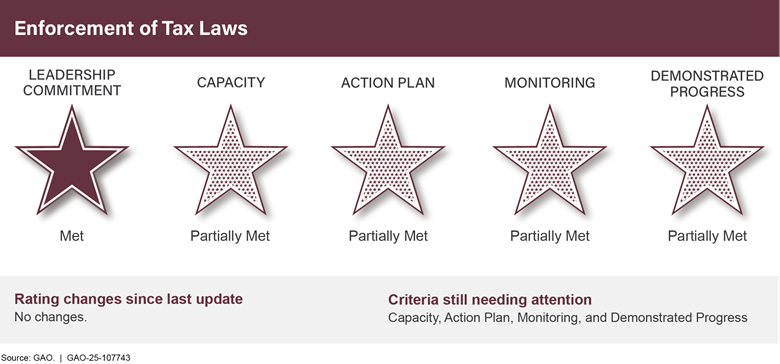

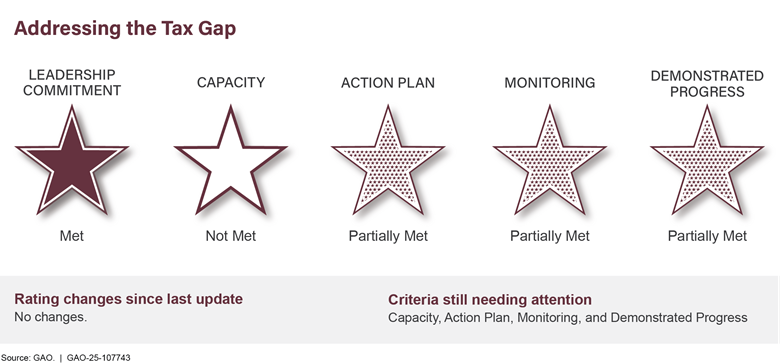

Enforcement of Tax Lawsa |

● |

|

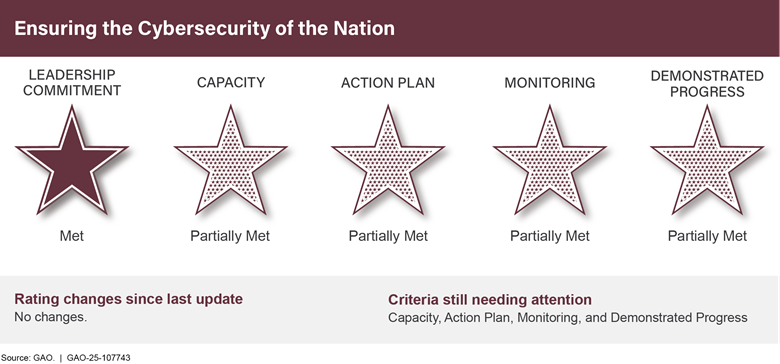

Ensuring the Cybersecurity of the Nationa,b |

● |

|

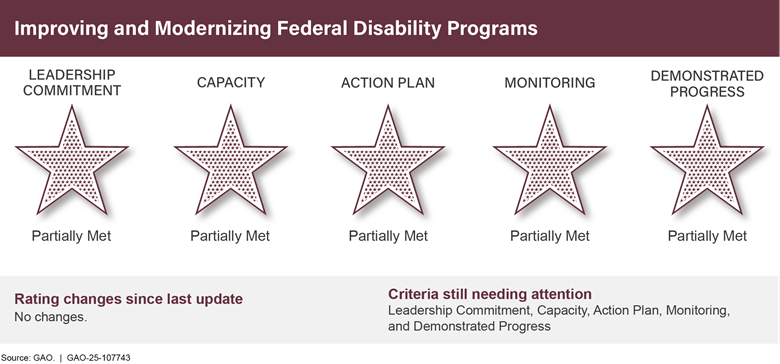

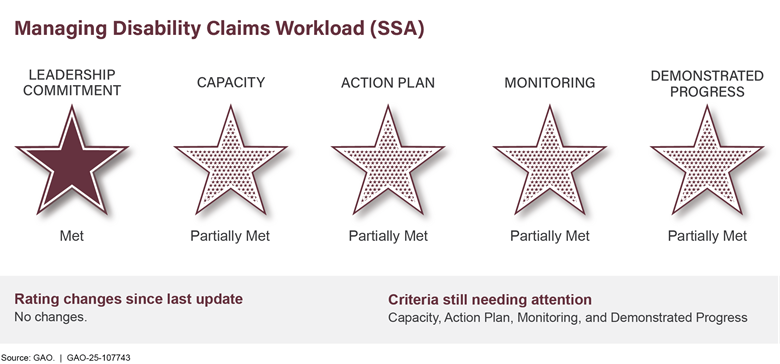

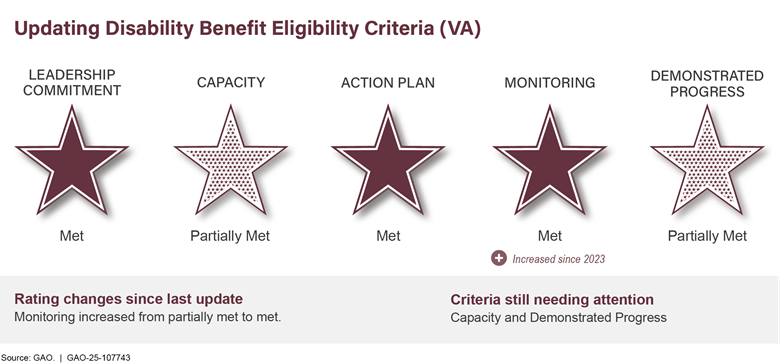

Improving and Modernizing Federal Disability Programsb |

● |

|

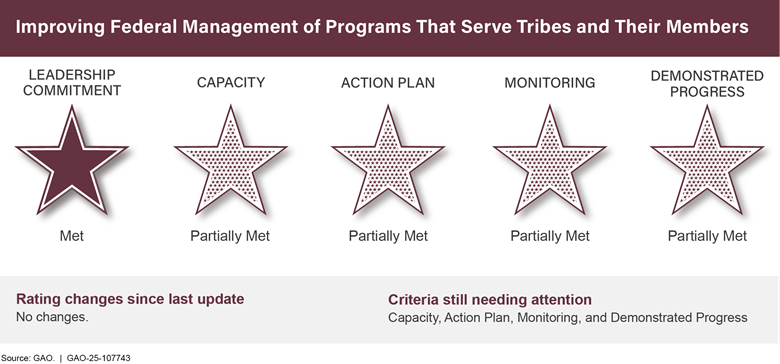

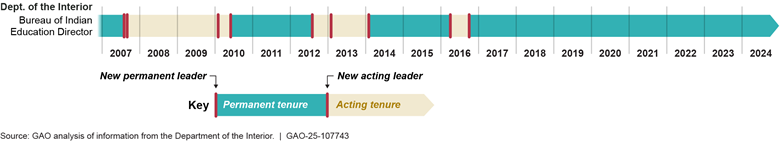

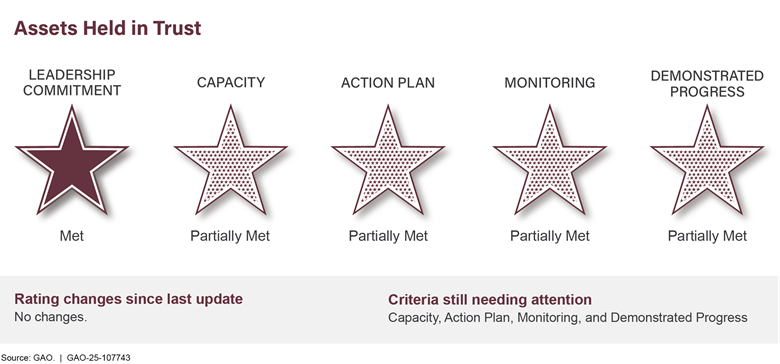

Improving Federal Management of Programs that Serve Tribes and Their Membersb |

● |

|

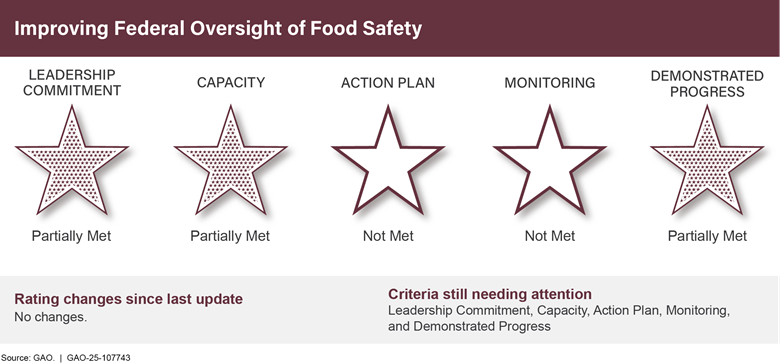

Improving Federal Oversight of Food Safetya,b |

● |

|

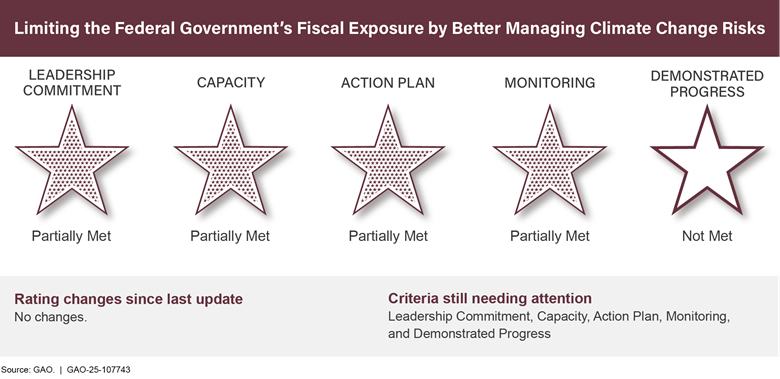

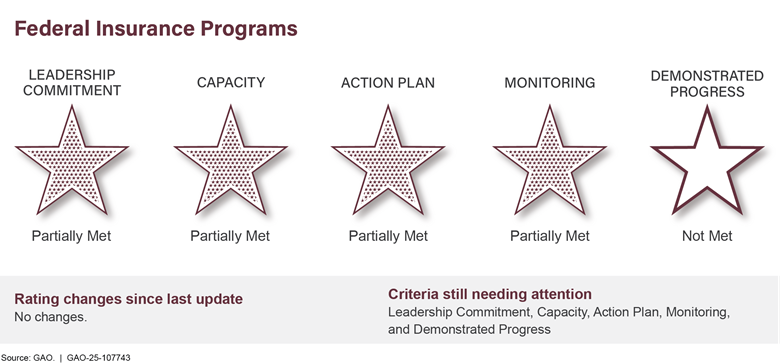

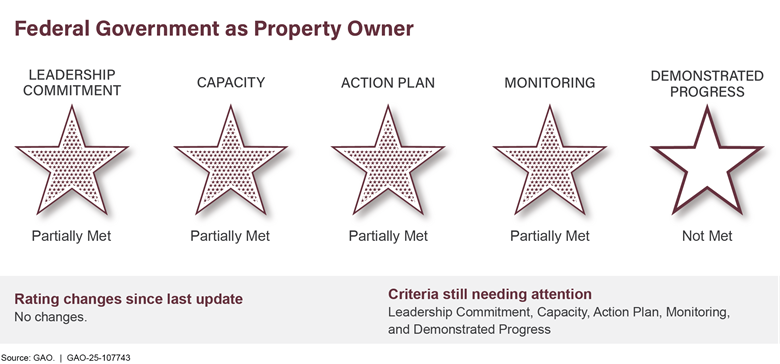

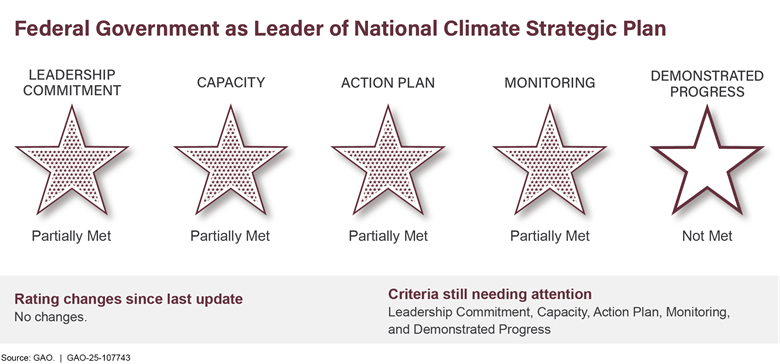

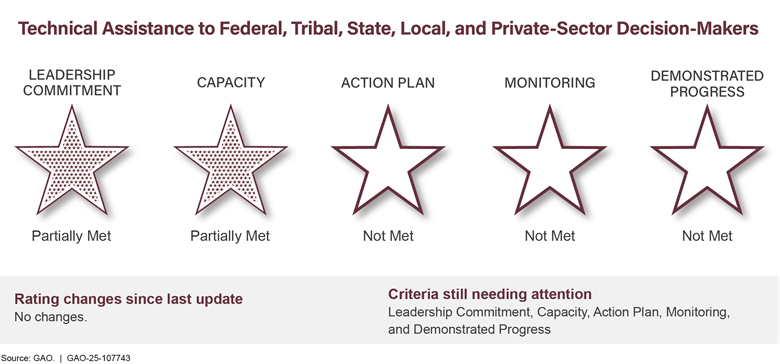

Limiting the Federal Government’s Fiscal Exposure by Better Managing Climate Change Risksa,b |

● |

|

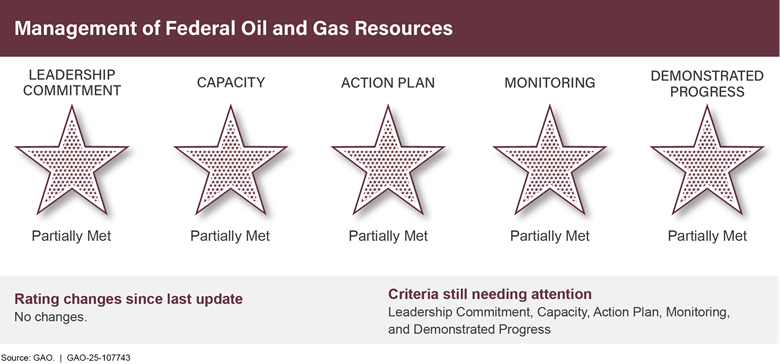

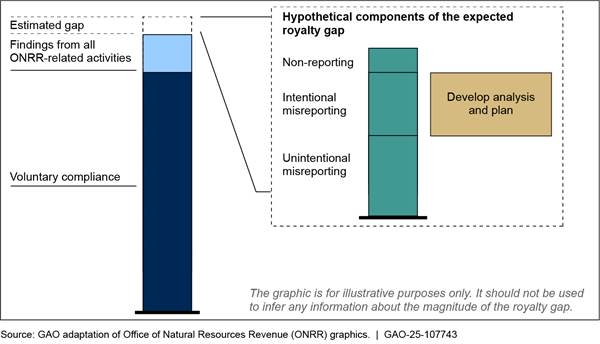

Management of Federal Oil and Gas Resources |

● |

|

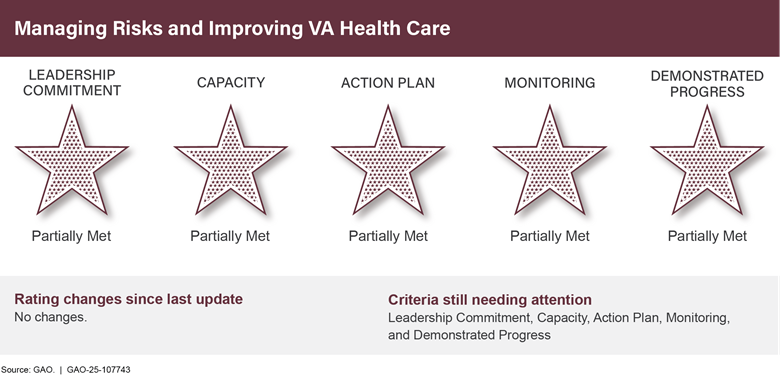

Managing Risks and Improving VA Health Care |

● |

|

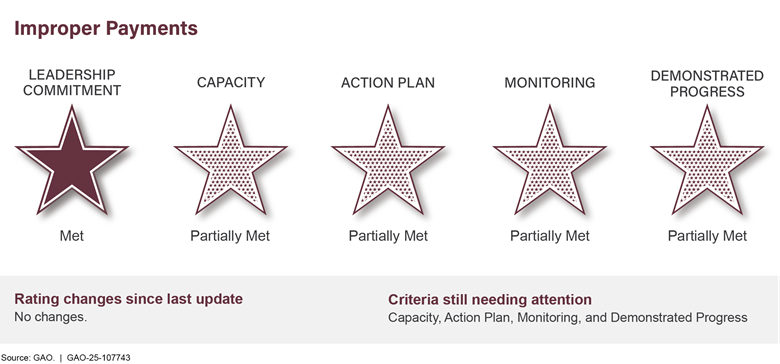

Medicare Program and Improper Paymentsa |

● |

|

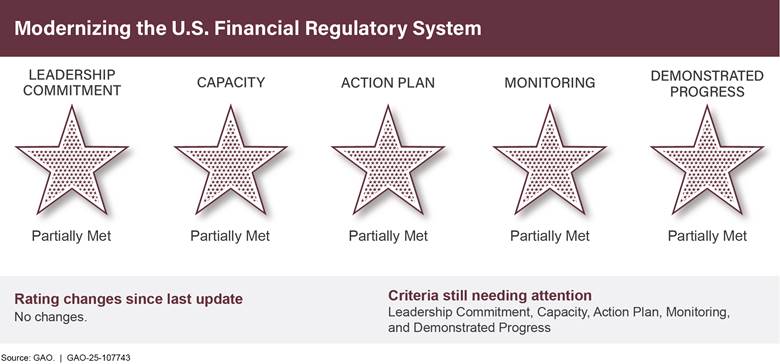

Modernizing the U.S. Financial Regulatory Systema,b |

● |

|

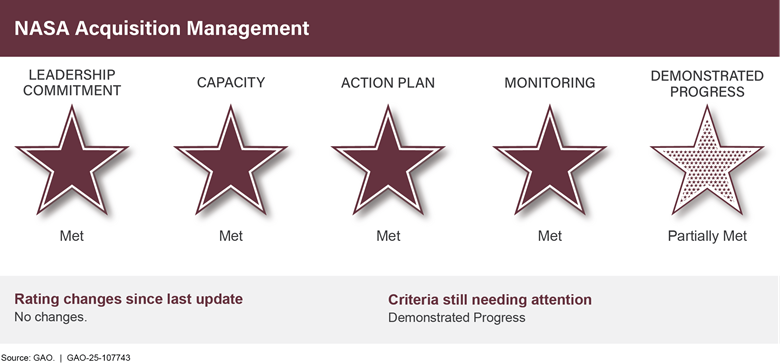

NASA Acquisition Management |

● |

|

Protecting Public Health Through Enhanced Oversight of Medical Products |

● |

|

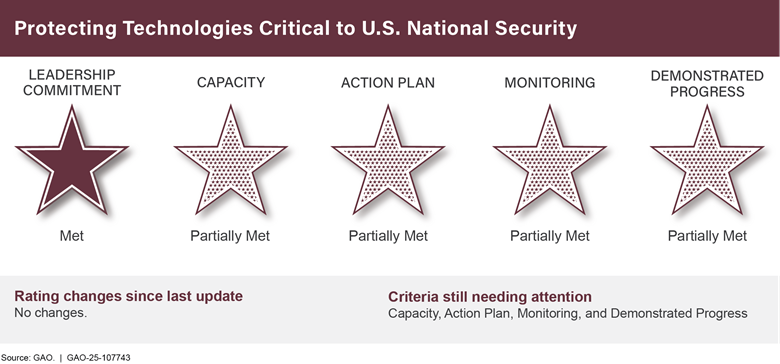

Protecting Technologies Critical to U.S. National Securityb |

● |

|

Strategic Human Capital Managementb |

● |

|

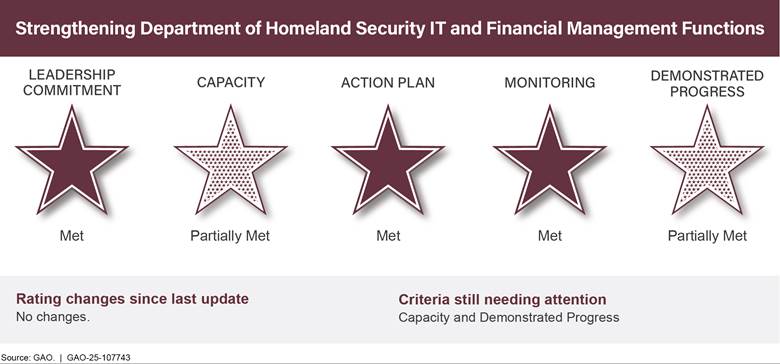

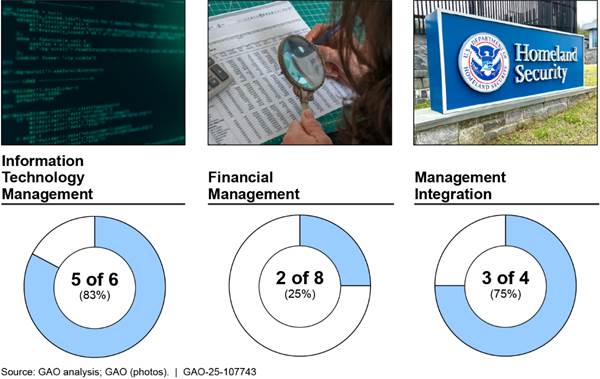

Strengthening Department of Homeland Security IT and Financial Management Functions |

● |

|

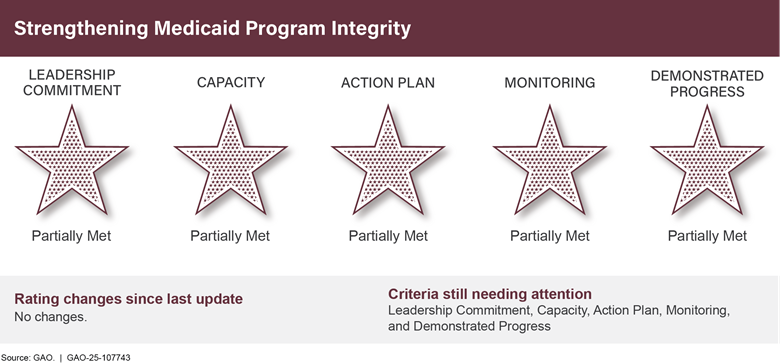

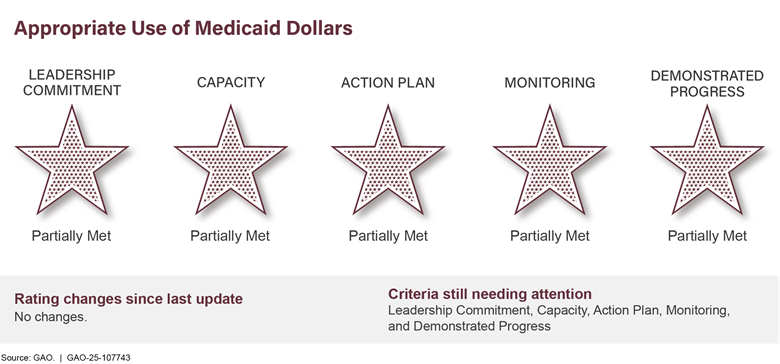

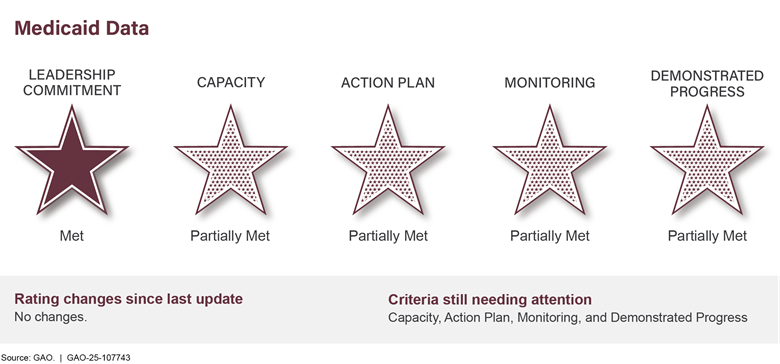

Strengthening Medicaid Program Integritya,b |

● |

|

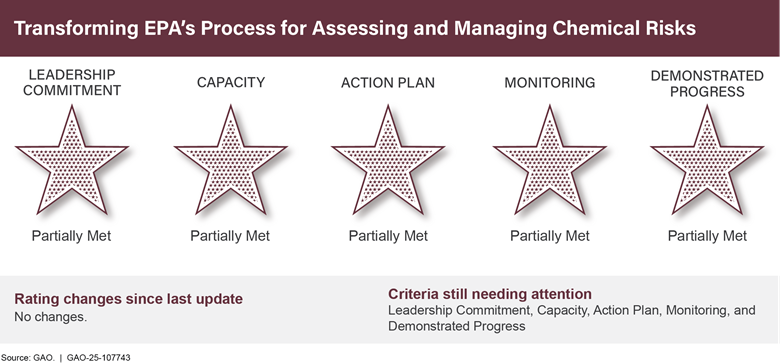

Transforming EPA’s Process for Assessing and Managing Chemical Risks |

● |

|

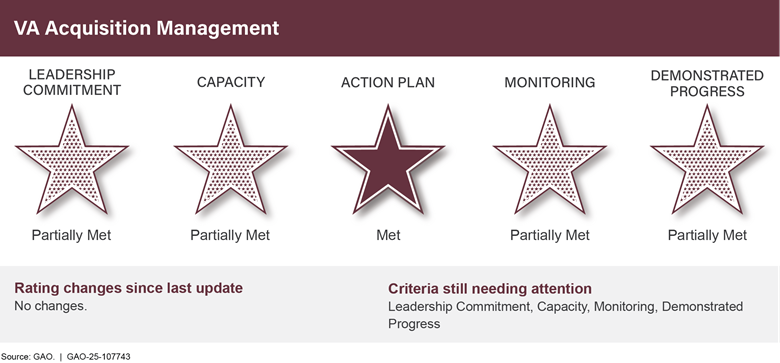

VA Acquisition Management |

● |

Legend: h indicates area progressed on

one or more criteria since 2023; i indicates area declined on one or more

criteria since 2023;

● indicates no change since 2023;

n/a = not applicable

Source: GAO. | GAO-25-107743

aLegislation is likely to be necessary to effectively address this high-risk area.

bCoordinated efforts across multiple entities are necessary to effectively address this high-risk area.

February 25, 2025

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable James Comer

Chairman

The Honorable Gerald E. Connolly

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

Since the early 1990s, our high-risk program has focused attention on government operations with significant vulnerabilities to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement or that need transformation to address economy, efficiency, or effectiveness challenges. This effort, supported by the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs and the House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, has brought much-needed attention to problems impeding effective government and costing billions of dollars each year.

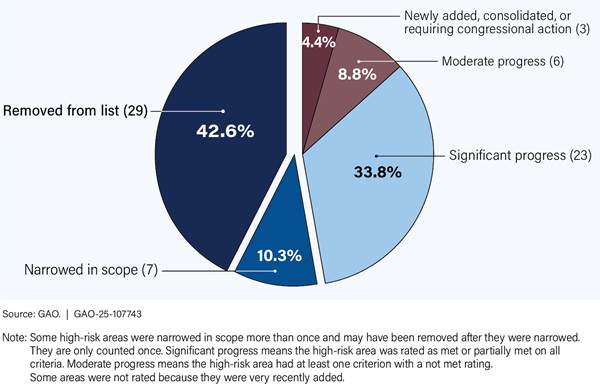

About 53 percent of high-risk areas identified over the years have either been removed from the list or narrowed in scope. Significant progress has been made on many other areas, as they have met or partially met all five criteria for removal (see fig. 1).

The federal government is one of the world’s largest and most complex entities. About $6.8 trillion in outlays in fiscal year 2024 funded a broad array of programs and operations.

Efforts to address high-risk issues have contributed to hundreds of billions of dollars saved. Over the past 19 years (fiscal years 2006 through 2024), these financial benefits totaled nearly $759 billion or an average of about $40 billion per year. Since our last update in 2023, we recorded approximately $84 billion in financial benefits as agencies took action to address high-risk areas. Progress on high-risk areas has also resulted in many other benefits that cannot be measured in dollar terms, such as improved service to the public and enhanced ability to achieve agency missions. Further progress to narrow or remove the 38 areas remaining on the High-Risk List can help save billions more dollars, improve services to the public, and increase government performance and accountability.

Congressional action, such as passing laws and holding hearings, is critical for making meaningful progress on high-risk areas. Table 1 lists examples of congressional actions that helped make progress on high-risk areas.

|

High-risk area |

Congressional actions |

|

HHS Leadership and Coordination of Public Health Emergencies |

Congress established the Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy in 2022 within the Executive Office of the President by enacting the Prepare for and Respond to Existing Viruses, Emerging New Threats, and Pandemics Act (PREVENT Pandemics Act).a This office, which launched in July 2023, is charged with coordinating federal activities to prepare for, and respond to, pandemic and other biological threats. |

|

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025 established the position of DOD Performance Improvement Officer in statute and gave the position responsibilities related to performance improvement, business reform and transformation efforts, and DOD’s Strategic Management Plan.b |

|

|

In 2022, Congress mandated that DOD establish a target goal for completing cleanup of sites contaminated by military munitions.c |

|

|

Congress held hearings in April and December 2024 on changes to the U.S. Postal Service’s delivery network, on-time delivery performance, financial viability, and implementation of the Postal Service Reform Act of 2022. |

|

|

Congress helped the Department of Defense (DOD) address some gaps in senior leadership and mitigate risks to its industrial base (the large collection of companies that provide supplies, parts, and manufacturing for DOD’s weapons systems). The Senate confirmed DOD’s first Assistant Secretary for Industrial Base Policy in March 2023, who issued DOD’s first National Defense Industrial Strategy in January 2024. Further, legislation, such as acquisition reforms required by the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, has prompted DOD to consider how to address structural barriers that impede its progress in making change, such as its requirements process.d |

|

|

In December 2023, the Senate confirmed the second National Cyber Director. The presence of this leadership should facilitate the high-level attention and coordination needed to address cyber threats and challenges facing the nation. |

|

|

Limiting the Federal Government’s Fiscal Exposure by Better Managing Climate Change Risks |

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 directed DOD to incorporate the impact of military installation environmental resilience into certain guidance documents.e For example, guidance documents should define specific military installation resilience hazards—such as wind, wildfire, and flooding—to ensure consistent impact reporting across DOD. |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107743

aConsolidated Appropriations Act, 2023. Pub. L. No. 117-328, div. F, tit. II, 136 Stat. 4459, 5706 (2022).

bNational Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025, Pub. L. No. 118-159, 902 (2024).

cNational Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-31, 137 Stat. 136 (2023).

dJames M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, Pub. L. No. 117-263, 326, 136 Stat. 2395, 2518-19 (2022).

eNational Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-31, 2857, 137 Stat. 136, 767 (2023).

Agency leaders took actions to implement our recommendations in some high-risk areas, resulting in significant financial benefits (see table 2).

|

High-risk area |

Executive actions |

|

To prevent potential fraud in the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), the Small Business Administration (SBA) established additional controls for PPP loans, as we recommended. In June 2023, SBA reported that the agency prevented the funding of 174,000 potentially ineligible or fraudulent PPP applications (after they were initially approved by lenders), representing $3.6 billion in net potential savings. By applying similar controls to two other pandemic programs, SBA detected and prevented about 4,600 potentially ineligible or fraudulent Shuttered Venue Operators Grant Program applications since its launch in April 2021 and about 31,000 Restaurant Revitalization Fund applications since its launch in May 2021, representing $2.1 billion and $2.8 billion in net potential savings, respectively. SBA has continued to review and deny PPP forgiveness applications since January 2022, saving about $2.9 billion as of July 2023. |

|

|

The annual premiums collected by the National Flood Insurance Program are generally insufficient to cover high losses, especially in years of catastrophic flooding. As we recommended, Federal Emergency Management Agency adjusted its rate‑setting methodology in October 2021. This improved the accuracy of the premiums charged and reduced financial risk to taxpayers and the federal government, resulting in savings of $1.24 billion from fiscal years 2022 through 2024. |

|

|

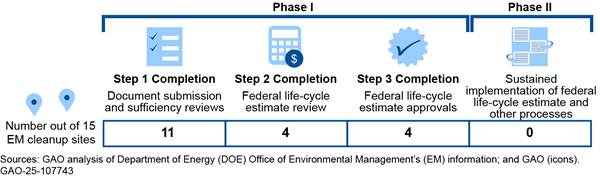

In April 2024, the Department of Energy (DOE) and regulators at the Hanford Site in Washington State proposed an agreement under which DOE would treat millions of gallons of low-activity radioactive waste using grout instead of glass. We recommended in December 2021 that DOE analyze additional disposal options for this waste, including identifying facilities that could receive grouted low-activity waste from Hanford. We estimate that this approach will save about $7.5 billion if DOE can move forward as planned under a finalized agreement with Hanford regulators. In May 2024, the DOE’s Office of Environmental Management (EM) announced that it does not plan to resume construction of its $12 billion Pretreatment Facility at Hanford. We have repeatedly recommended that EM pause construction on the Pretreatment Facility until it resolved significant technical issues. EM plans to keep the facility in standby until at least 2029 while evaluating pretreatment options, saving $6 billion over 5 years. In March 2023, EM completed a program-wide strategy and reviewed opportunities to balance cleanup costs with health and environmental risks. This resulted in the decision to accelerate the cleanup of certain nuclear waste at EM’s Savannah River Site in South Carolina by an estimated 22 years, avoiding more than $2.4 billion in costs. |

|

|

The National Institute on Aging (NIA) initiated an IT project to improve research into Alzheimer’s disease by compiling and analyzing real world data. In March 2024, Congress cited our ongoing work that found the NIA’s project minimally met the four characteristics of a reliable cost estimate. Congress urged the agency to pause planned awards for the project. In light of our work and other developments in Alzheimer’s research, NIA decided not to fund the project in April 2024, resulting in reduced expenses of approximately $282 million over 6 years. |

|

|

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) took actions to identify potentially ineligible COVID-19 related sick and family leave credit claims. This allowed IRS to recapture ineligible refunds and adjust taxes, resulting in additional collection of taxes of about $285.2 million as of March 2024. |

|

|

In November 2019, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) completed the phase-in of reduced payments for specific hospital outpatient services to more closely align with payments for the same services provided in physician practices, which our previous work supports.a CMS estimated the change saved the Medicare program about $864 million in fiscal year 2023. |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107743

a84 Fed. Reg. 61,142 (Nov. 12, 2019).

Substantial additional efforts are needed to achieve greater progress and to address backsliding in some high-risk areas since the 2023 update. Sustained congressional attention and executive branch leadership remain key to success.

This report describes (1) high-risk areas needing significant attention; (2) progress made addressing high-risk areas, the reasons for that progress, and the resulting benefits from agency and congressional actions; and (3) additional actions that are still needed. We identified one new high-risk area in 2025. This high-risk area—Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistance—is being added because of the increasing cost and complexity of federal support as disasters become more frequent and intense.

This update is based primarily on reports we issued before February 2025. High-risk area ratings are based on analysis of agency actions taken up through and including the 118th Congress, before the start of the 119th Congress and the new administration. We will continue to monitor and evaluate ongoing agency and congressional actions, which will be reflected in our 2027 high-risk update.

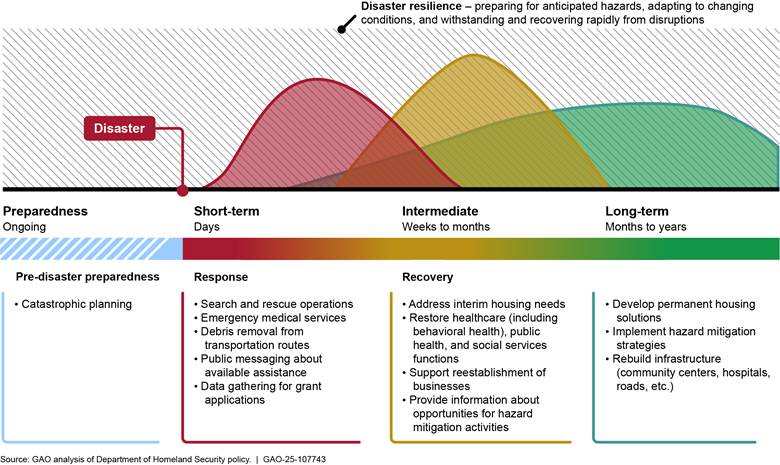

New High-Risk Area: Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistance

Natural disasters have become costlier and more frequent. In 2024, there were 27 disasters with at least $1 billion in economic damages. Overall, these events resulted in 568 deaths and significant economic effects on affected areas. Their frequency and intensity have severely strained the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and its workforce.

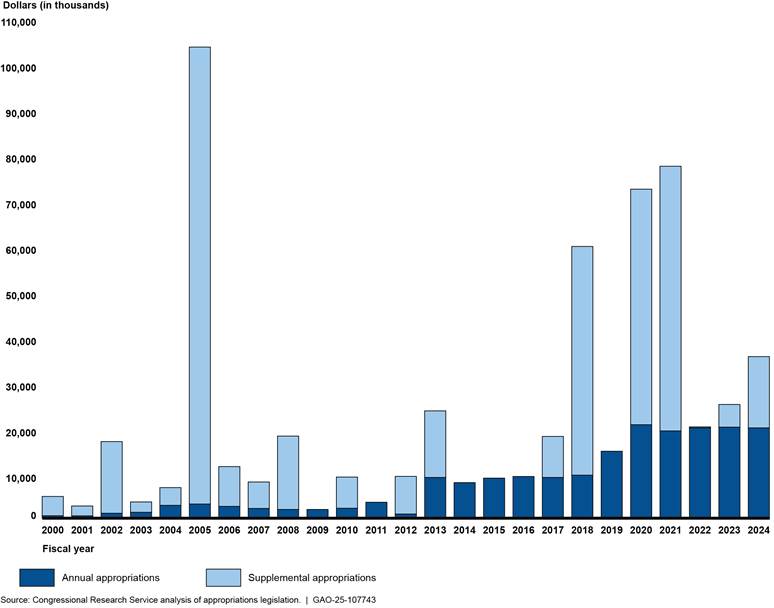

Recent natural disasters—including wildfires in Southern California and hurricanes in the Southeast (see fig. 2)—demonstrate the need for federal agencies to deliver assistance as efficiently and effectively as possible and reduce their fiscal exposure. For fiscal years 2015 through 2024, appropriations for disaster assistance totaled at least $448 billion.[1] Additionally, in December 2024 the Disaster Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2025, appropriated $110 billion in supplemental appropriations for disaster assistance.[2]

The federal approach to disaster recovery is fragmented across over 30 federal entities. So many entities involved with multiple programs and authorities, differing requirements and timeframes, and limited data sharing across entities could make it harder for survivors and communities to navigate federal programs.

FEMA and other federal entities—including Congress—need to address the nation’s fragmented federal approach to disaster recovery. Attention is also needed to improve processes for assisting survivors, invest in resilience, and strengthen FEMA’s disaster workforce and capacity.

High-Risk Areas Needing Significant Attention

While all high-risk areas should make more progress, the areas described below require significant attention. These areas feature emerging issues requiring government responses, large and rapidly growing costs, or a failure to make any progress in the past several years.

|

|

Reducing Billions in Significant Improper Payments and Fraud |

Several Areas Critical to Better Managing the Cost of Government

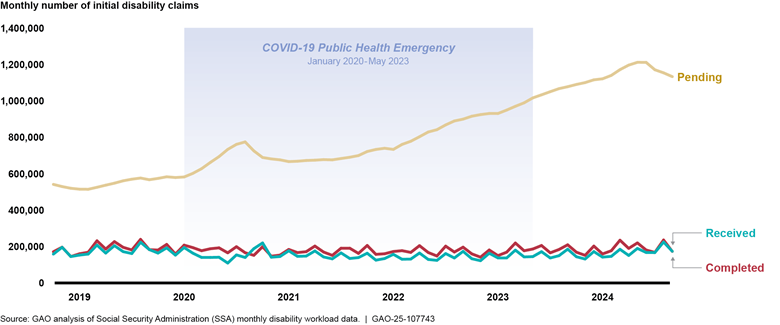

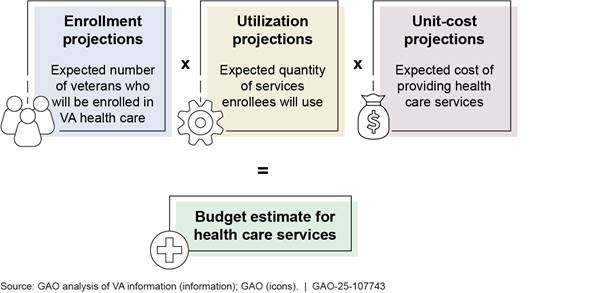

Since 2003, federal agencies have reported about $2.8 trillion in estimated improper payments, including more than $150 billion government-wide in each of the last 7 years (see fig. 3).[3] These figures do not represent a full accounting of improper payments because agencies have not reported estimates for some programs as required. For example, we found that agencies failed to report fiscal year 2023 improper payment estimates for nine risk-susceptible programs.[4]

The areas on the High-Risk List include programs that represented about 80 percent of the total government-wide reported improper payment estimate for fiscal year 2023. These include two of the fastest-growing programs—Medicare and Medicaid—as well as the unemployment insurance system and the Earned Income Tax Credit. While agencies and the Department of the Treasury are taking some steps to address this issue, much more needs to be done to control billions of dollars in overpayments and prevent fraud. Implementation of our recommendations by agencies and the Congress would help achieve better program integrity.

|

|

Closing Large Gaps in Revenue Owed to the Government |

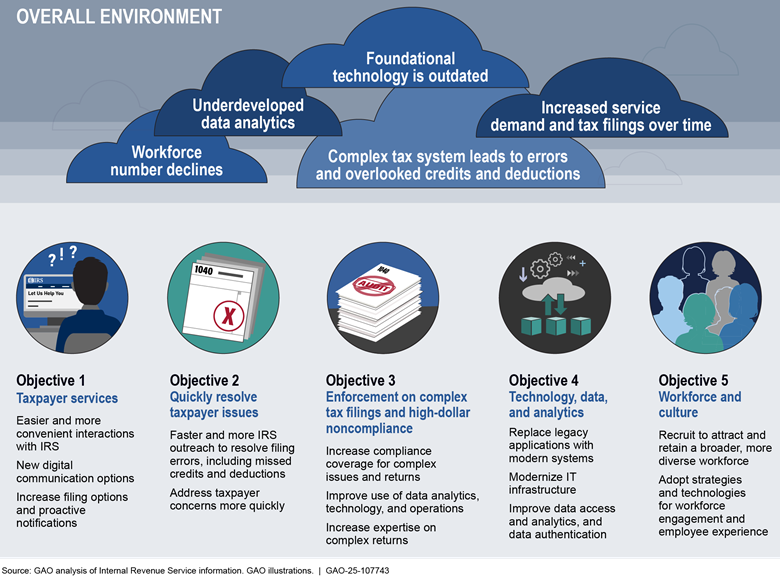

In 2024, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) projected that the gross tax gap—the difference between taxes owed and taxes paid on time—was $696 billion for tax year 2022 (see fig. 4). IRS estimated that it will collect an additional $90 billion through late payments and enforcement actions, leaving an estimated $606 billion net tax gap.

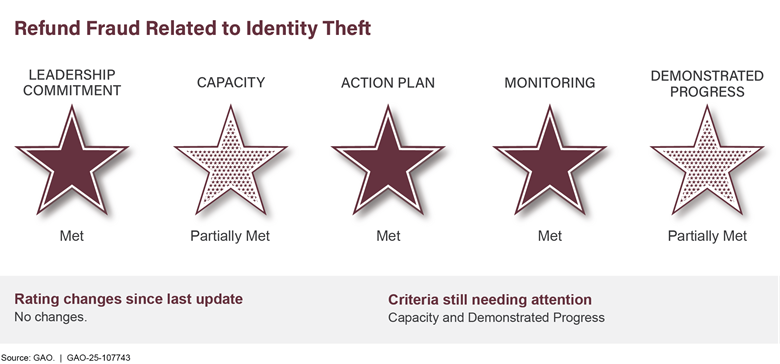

IRS is also continually addressing billions of dollars of attempted tax fraud through identity theft. Further, the Department of the Interior does not have reasonable assurance that it is collecting the entirety of the billions owed on oil and gas leases on federal lands. Actions by federal agencies and Congress on related GAO recommendations can help significantly to close these gaps and improve the government’s fiscal position.

|

|

Better Controlling Cost Growth and Schedule Delays in High Dollar Value Procurements |

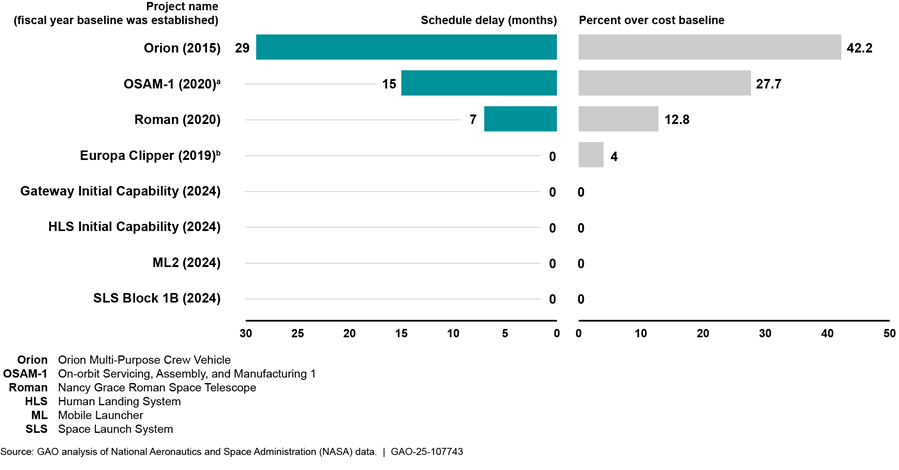

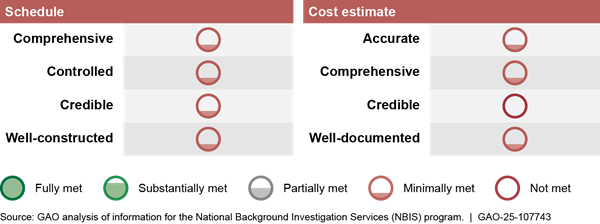

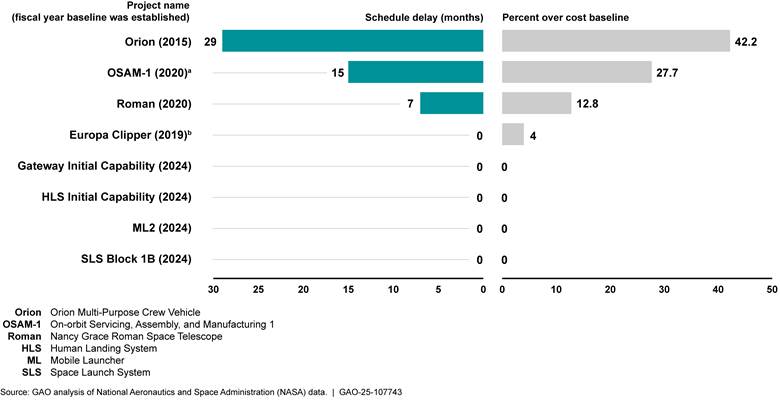

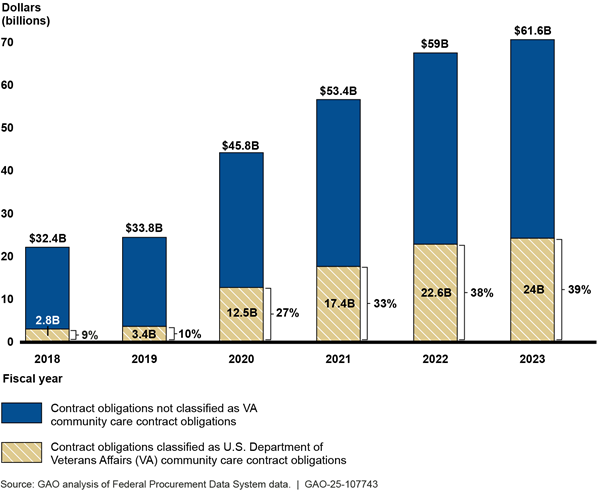

The government has great difficulty in controlling the costs of high dollar value acquisitions in its more than $750 billion procurement portfolio. This includes procurements critical to national defense, nuclear weapon systems modernization and cleanup, space programs, and health care to veterans. Many major acquisitions by agencies such as the Department of Defense (DOD), the Department of Energy, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) have experienced cost growth, schedule delays, or both.

For example, NASA is developing eight projects which each exceed $2 billion in life-cycle costs, known as category 1 projects. Three of them were experiencing schedule delays and four exceeded their cost baseline as of mid-2024 (see fig. 5).

Note: Data are as of July 2024. The Commercial Crew Program, which is also a category 1 project, is excluded from this analysis because it has a tailored project life cycle and project management requirements and did not establish a baseline.

aNASA announced in March 2024 that it planned to discontinue OSAM-1 due to continued technical, cost, and schedule challenges, among other reasons. As of October 1, 2024, NASA was in the process of shutting down the project.

bThe Europa Clipper project launched 11 months ahead of its schedule baseline in October 2024.

Implementation of our recommendations, such as more consistently applying leading practices, could yield billions in savings and provide faster delivery of innovative capability.

|

|

Rightsizing the Government’s Property Holdings Could Generate Substantial Savings |

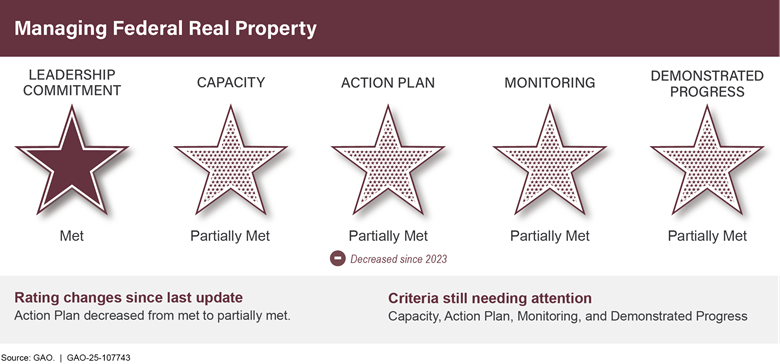

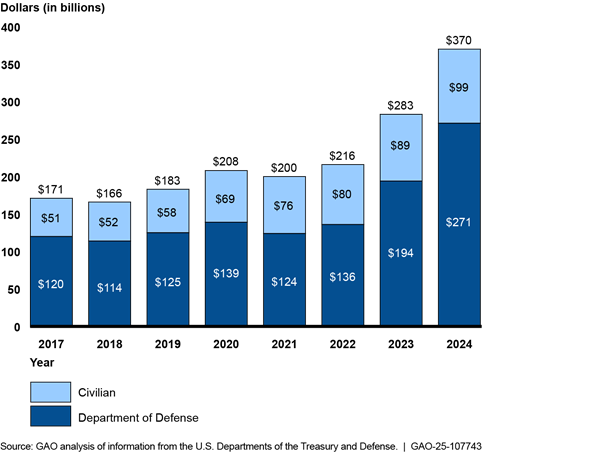

The federal government is one of the nation’s largest property holders. Annual maintenance and operating costs for its 277,000 buildings exceeded $10.3 billion in fiscal year 2023. Managing real property was designated high risk in 2003 because of large amounts of underused property and the great difficulty in disposing of unneeded holdings and ensuring safety of workers and visitors. Costliness and underuse of government property holdings have been exacerbated by the recent use of telework and growing amounts of deferred maintenance, which rose from $170 billion in 2017 to $370 billion in 2024 (see fig. 6).

Figure 6: Federal Civilian Agencies’ and U.S. Department of Defense Reported Estimates of Deferred Maintenance and Repairs, Fiscal Years 2017–2024

We recommended more appropriate utilization benchmarks be established to guide better and more timely property management. Also, lessons need to be applied from recent failed attempts to expedite disposals to establish a more viable process. Efforts are also needed to better manage and maintain property.

|

|

Achieving Greater Financial Management Discipline at DOD |

DOD is the only major federal agency to have never achieved an unmodified “clean” opinion on its financial statements. The department is committed to the goal of achieving a clean opinion on its statements and has made important progress in reaping several financial and operational benefits (see fig. 7).

A clean opinion was recently obtained by the Marine Corps, in addition to several smaller components. DOD needs to redouble its efforts to revamp financial management systems, more promptly fix problems identified by its auditors, and focus more on ensuring a well-qualified workforce to attain proper accountability and potential savings.

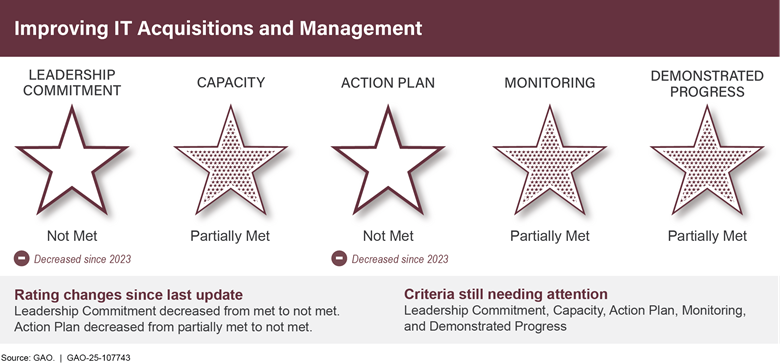

Harnessing Modern Information Technology to Improve Services and Programs

The federal government spends over $100 billion annually on IT, with the vast majority of this spent on operations and maintenance of existing systems rather than new technology. Currently, the government, in many cases, is carrying out critical missions with decades-old legacy technology that also carries tremendous security vulnerabilities. Many attempts to implement new systems have too often run far over budget, experienced significant delays, and delivered far fewer improvements than promised. Recent challenges at the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Department of Education, and VA vividly illustrate this situation.

· FAA has been experiencing increasing challenges with aging air traffic control systems in recent years and has been slow to modernize the most critical and at-risk systems. A 2023 operational risk assessment determined that of FAA’s 138 systems, 51 (37 percent) were unsustainable with significant shortages in spare parts, shortfalls in sustainment funding, little to no technology refresh funding, or significant shortfalls in capability. An additional 54 (39 percent) were potentially unsustainable.

· The Department of Education’s Office of Federal Student Aid did not adequately plan for its deployment of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) Processing System. The initial rollout of the new system was delayed several times and faced several critical technical issues and very poor customer service. This contributed to about 9 percent fewer high school seniors and other first-time applicants submitting a FAFSA, as of August 25, 2024.

· After three unsuccessful attempts between 2001 and 2018 to replace its health records system, VA initiated a fourth effort—the electronic health record (EHR) modernization program. In 2022, the Institute for Defense Analysis estimated that EHR modernization life cycle costs would total $49.8 billion—$32.7 billion for 13 years of implementation and $17.1 billion for 15 years of sustainment. As of December 2024, VA deployed the EHR system to just six of its locations and plans to deploy it at four more locations in 2026. There are over 160 remaining locations for EHR implementation.

These are examples of poor performance that led us to designate Improving IT Acquisitions and Management as a government-wide high-risk area in 2015. There have been some improvements, including closing unneeded data centers, which saved billions of dollars. Congressional oversight by the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Subcommittee on Government Operations, has helped spur improvements and included exhortations to have Chief Information Officers (CIO) more involved.

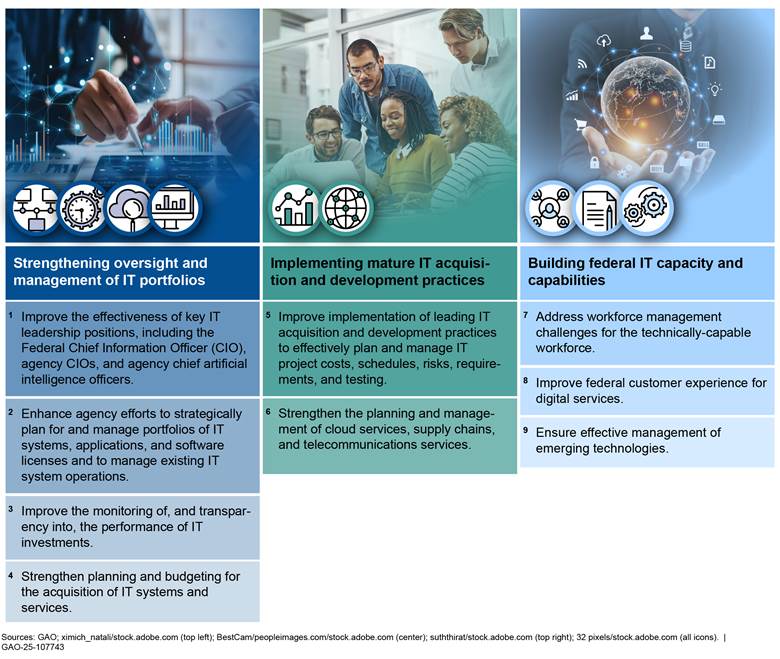

Agencies need to urgently address nine critical actions associated with three major IT management challenges that we have identified (see fig. 8).

Figure 8: Nine Critical Actions Federal Agencies Need to Take to Address Three Major IT Management Challenges

Of the 1,881 recommendations we made for this high-risk area since 2010, 463 remained open as of January 2025. Agency leaders need to give this area a higher priority and provide their CIOs necessary authorities and support if the government is ever to reap the benefits of modern technology.

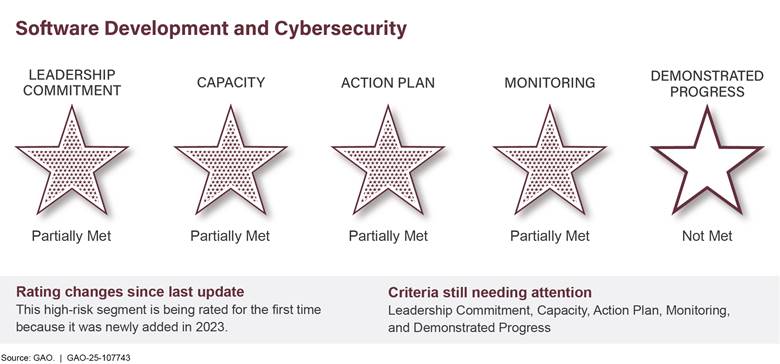

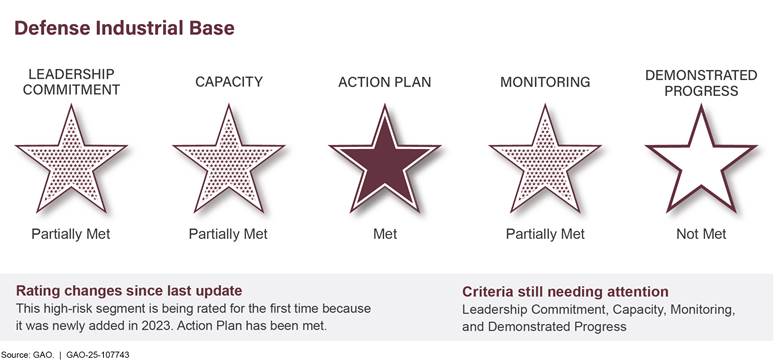

Expediting the Pace of Cybersecurity and Critical Infrastructure Protections

While improvements have been made and efforts continue, the government is still not operating at a pace commensurate with the evolving grave cybersecurity threats to our nation’s security, economy, and well-being. State and non-state actors are attacking our government and private-sector systems thousands of times each day. In addition to national security and intellectual property, systems supporting daily life of the American people are at risk, including safe water, ample supply of energy, reliable and secure telecommunications, and our financial services.

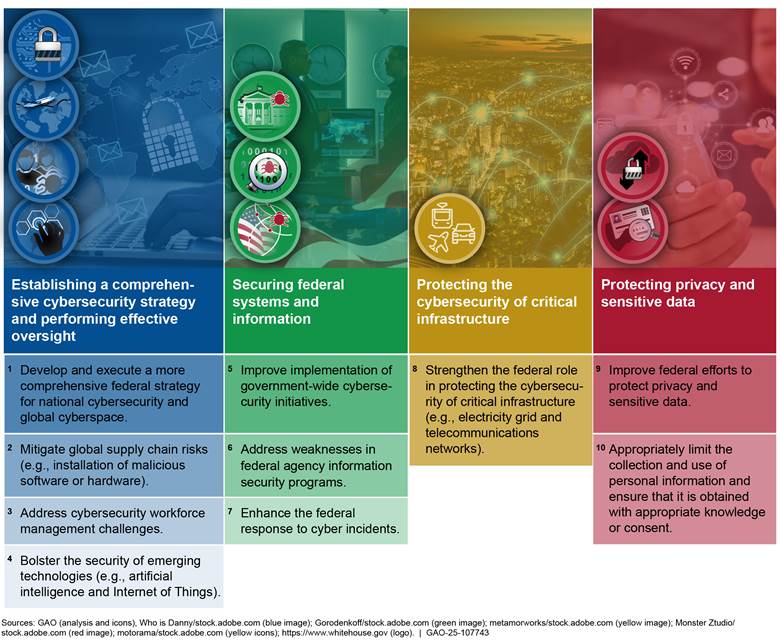

Agencies need to urgently address 10 critical actions associated with four major cybersecurity challenges (see fig. 9).

We have made 4,387 related recommendations since 2010. While 3,623 have been implemented or closed, 764 have not been fully implemented. Also, greater federal efforts are needed to better understand the status of private sector technological developments with cybersecurity implications—such as artificial intelligence—and to continue to enhance public and private sector coordination.

Seizing Opportunities to Better Protect Public Health and Reduce Risk

Several high-risk areas focus on addressing critical weaknesses in public health efforts. Our recommendations focus on

· ensuring the Department of Health and Human Services significantly elevates its ability to provide leadership and coordination of public health emergencies;

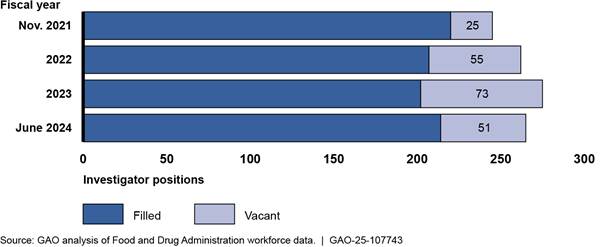

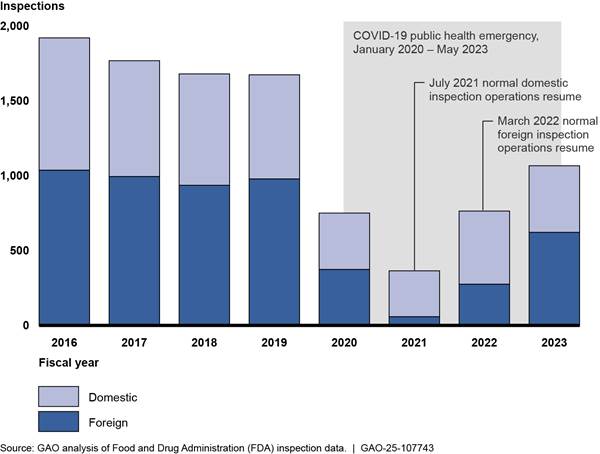

· providing the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) with a much greater capacity to (1) inspect foreign drug manufacturers that produce many of the drugs consumed by Americans, and (2) take stronger actions to address persistent drug shortages, including cancer therapies;

· improving the timeliness and quality of care given to our veterans, including mental health and suicide prevention, especially in rural areas;

· ensuring better health care by the Indian Health Service to Tribes and their members;

· providing national leadership to prevent drug abuse and further reduce overdose deaths; and

· ensuring the Environmental Protection Agency provides more timely reviews of potentially toxic chemicals before they are introduced into commercial production and widespread public use.

There is also a need for a more comprehensive approach to food safety to address fragmentation among 15 different federal agencies and at least 30 federal laws. While the United States has one of the safest food supplies in the world, every year millions of people are sickened by foodborne illnesses, tens of thousands are hospitalized, and thousands die. A more proactive, coordinated approach that takes greater advantage of modern technology would be in the best interest of Americans and would lead to a more efficient government.

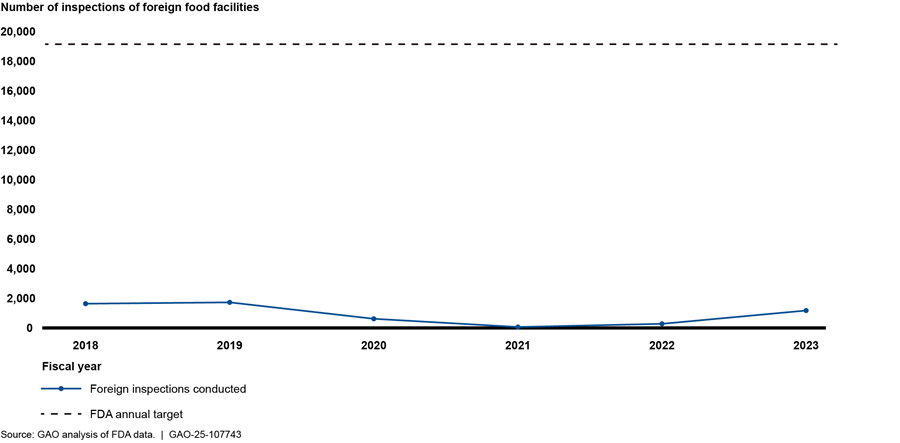

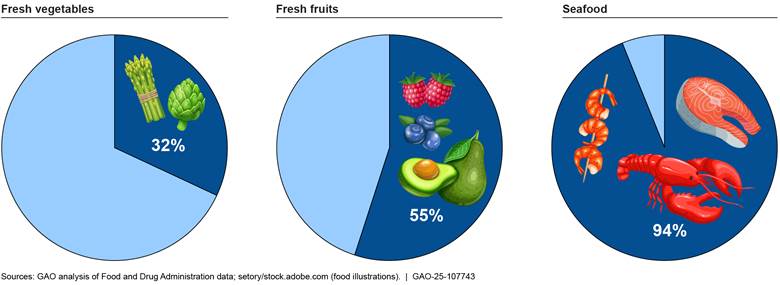

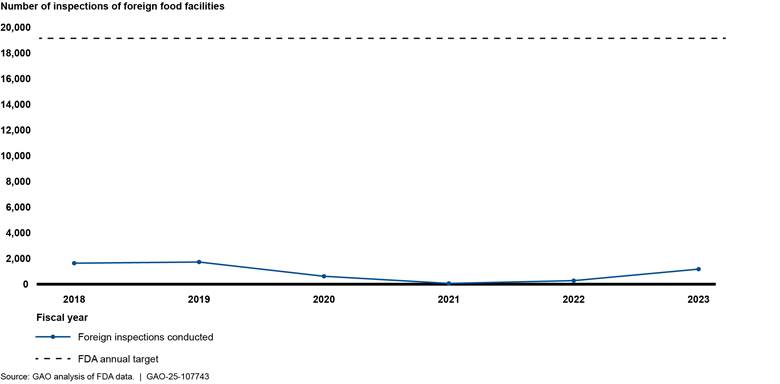

Further, the FDA has struggled to meet inspection targets for foreign and domestic food facilities because of limited capacity and workforce. For example, it only conducted an average of 917 foreign food safety inspections each year from fiscal years 2018 through 2023, about 5 percent of its target of 19,200 annual inspections for this period (see fig. 10). In fiscal year 2023, FDA conducted a total of 1,175 foreign inspections—far fewer than its annual target of 19,200 inspections, according to FDA data. Also, according to FDA data, in 2023 FDA did not inspect—or attempt to inspect—about 41 percent of high-risk domestic food facilities and about 55 percent of non-high-risk domestic food facilities by the date they were due for inspection.

Figure 10: Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Performance in Meeting Annual Targets for Foreign Food Facility Inspections According to FDA Data, Fiscal Years 2018–2023

Note: FDA has interpreted the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act to require that, beginning in 2016, the agency inspect 19,200 foreign facilities per year. FDA includes both completed and attempted inspections in its fiscal year totals to track its progress covering foreign food facilities in FDA’s inventory that are due for inspection. Attempted inspections occur when FDA investigators attempt to conduct an inspection of a food facility, but the inspection cannot be completed.

Other Concerning High-Risk Areas

|

|

Modernizing Our Financial Regulatory Systems |

Actions are needed to strengthen oversight of financial institutions and address regulatory gaps. The March 2023 bank failures and rapid adoption of emerging technologies in the marketplace have highlighted continued challenges in the regulatory system since we initially designated this area as high-risk in 2009 during the financial crisis. In particular, the Federal Reserve should improve procedures so that decisions to escalate supervisory concerns happen in a timely manner, and Congress should consider designating a federal regulator for certain crypto asset markets, as we recommended.

|

|

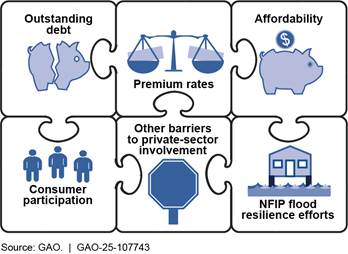

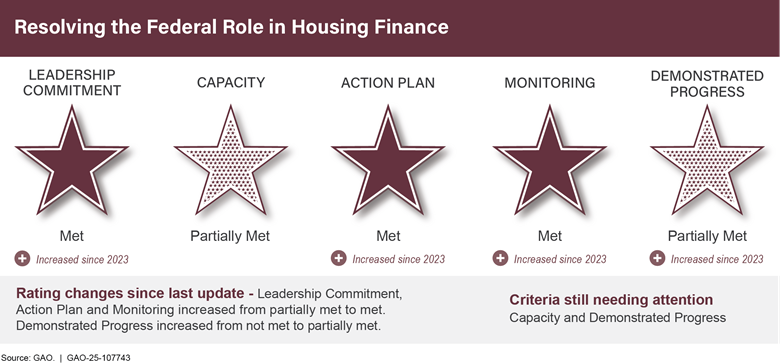

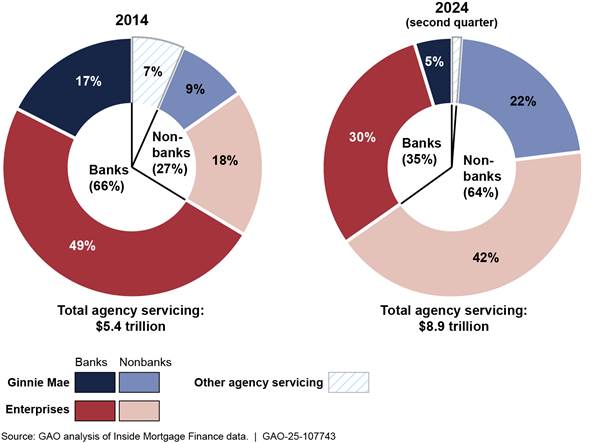

There is an essential need for Congress to clarify the federal role for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two private sector entities that provide underwriting for the U.S. mortgage market. They are still in federal conservatorship from the 2008 global financial crisis with no clear path forward. The other key federal players, Ginnie Mae and the Federal Housing Administration, have had their portfolios greatly expanded to nearly $2.7 trillion and $1.4 trillion, respectively. Consequently, the federal government is greatly exposed to a downturn in the housing market.

Federal housing and financial regulatory agencies have taken steps to strengthen the mortgage finance system. For example, they have adopted a final rule to implement quality control standards for automated mortgage valuation models.[5] Additionally, in September 2024, the Federal Housing Finance Agency launched a new dashboard for its joint initiative with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—the National Mortgage Database program, which helps examine the effect of mortgage market reforms. The dashboard reports publicly available quarterly data on residential mortgage performance.

To make further progress, federal housing agencies should continue to strengthen their oversight of the mortgage finance system. Congress should also determine the future federal role in this system and craft a plan to end federal conservatorship of the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac enterprises.

|

|

Addressing Long-Standing Issues with the Bureau of Prisons |

Prison buildings are deteriorating and in need of repair and maintenance while facilities are understaffed, putting both incarcerated people and staff at risk. Moreover, efforts to prevent recidivism have not been thoroughly evaluated, undermining a key goal to help incarcerated people transition into society once released.

The Bureau of Prisons (BOP) has made some progress in this high-risk area since our 2023 update. For example, in fiscal year 2023, BOP filled a newly created position for Chief of Addiction Medicine to further demonstrate BOP’s support of Opioid Use Disorder treatment. BOP also finalized a strategic framework outlining goals, strategies, and initiatives to direct its overall improvement efforts.

Further, in March 2024, BOP’s then Director agreed to a set of 22 metrics that we developed to gauge BOP’s progress in addressing this high-risk issue. These metrics include actions or efforts for BOP to improve its management of staff and resources, planning and monitoring, and its implementation of the First Step Act of 2018.[6]

|

|

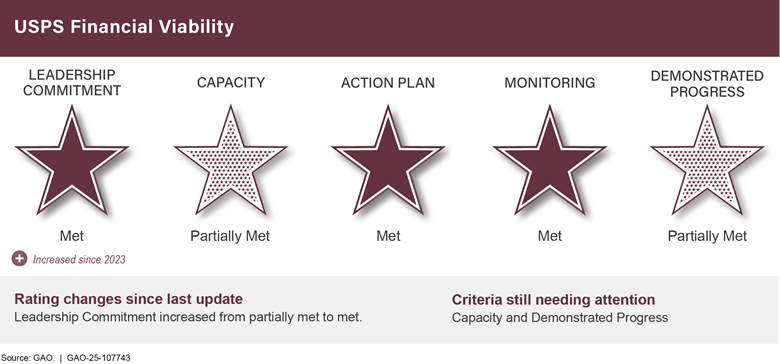

Fixing the United States Postal Service’s (USPS) Outdated Business Model |

Since our last update in 2023, USPS has taken further steps to implement its 10-year strategic plan released in March 2021. The Postmaster General, USPS’s executives, and its Board of Governors have all championed the plan and adjusted it to USPS’s changing operating environment and economic circumstances. In implementing this plan, USPS has worked to modernize and streamline its mail and package delivery network and improve the career development and retention of its workforce.

Congress acted to alleviate certain fiscal pressures and USPS is trying to reduce costs, but it is still losing money ($16 billion in fiscal years 2023 and 2024) and has extensive liabilities and debt ($181 billion in fiscal year 2024). USPS estimates that the fund supporting postal retiree benefits will be depleted in fiscal year 2031. At that point, USPS would be required to pay its share of retiree health care premiums, which USPS projects to be about $6 billion per year. There is a fundamental tension between the level of service Congress expects and what revenue USPS can reasonably be expected to generate. Congress needs to establish what services it wants USPS to provide and negotiate a balanced funding arrangement.

|

|

Addressing the Government’s Human Capital Challenges |

Twenty areas are on the High-Risk List in part due to skills gaps or an inadequate number of staff. Moreover, the personnel security clearance system is not yet being managed in the best manner to ensure that people are adequately screened to handle sensitive information.

OPM and agencies have taken some steps to assess and address skills gaps. For example, in June 2024, OPM identified the risks and mitigating strategies associated with its skills gaps, as we recommended. As a result, OPM is better positioned to monitor skills gaps across the agency and determine if risk mitigation strategies are successful.

In addition, in 2023, OPM conducted an analysis to identify common hiring needs across multiple agencies. OPM’s analysis helped establish a pooled hiring strategy that saves time and resources through a centralized coordination of federal government hiring to address skills gaps within the IT and human capital management workforce.

Ten High-Risk Areas Have Increased Their Progress Rating Since 2023

Ten high-risk areas improved since our last update in 2023. These areas are highlighted below and described in greater detail in appendix III.

|

|

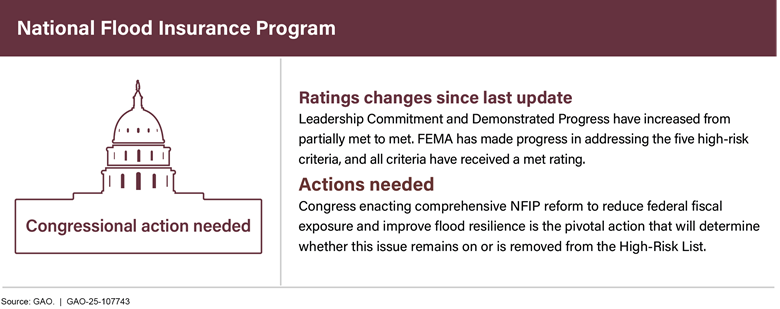

FEMA has taken an important step to help move NFIP toward financial solvency by implementing a revised premium rate-setting methodology that better aligns premiums with the flood risk of individual properties. FEMA leadership has also demonstrated its commitment to effectively administrating NFIP by continuing to implement our outstanding recommendations. As a result, the two remaining criteria that had not been met in 2023—leadership commitment and demonstrated progress—are now met.

Having met all five criteria, this area is now transitioning to congressional monitoring only. To make further progress, Congress needs to enact comprehensive reforms to NFIP that would address the program’s challenges.

|

|

DOD has taken significant action to establish its new approach to business transformation and to institutionalize this approach into its systems, processes, and governance structures. DOD has further developed its capacity to manage these efforts, including (1) increasing staffing for its Performance Improvement Directorate and (2) conducting assessments to determine whether it had the needed funding, staff, and other capabilities to support its priority performance improvement initiatives.

With its approach to business transformation now nearly in place, DOD’s attention has turned to implementation. To address remaining issues, DOD needs to demonstrate that its approach is leading to positive effects on its performance improvement efforts and meaningful improvements to its business operations. Once fully institutionalized and if effectively implemented, the department should be able to achieve and sustain business reform on a broad, strategic, department-wide, and integrated basis. DOD will need to assess and report on the results of its performance improvement initiatives over time to demonstrate that these efforts are leading to meaningful improvements.

|

|

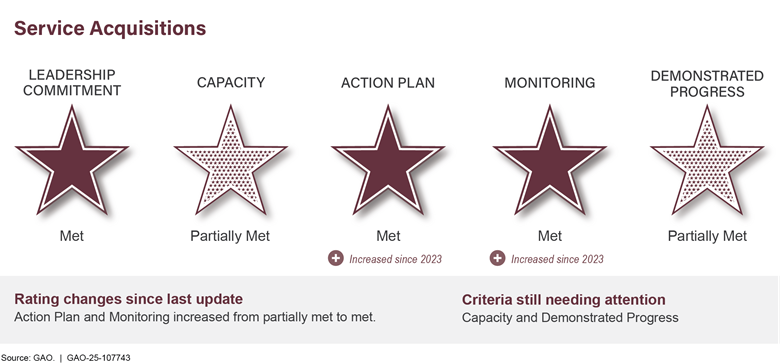

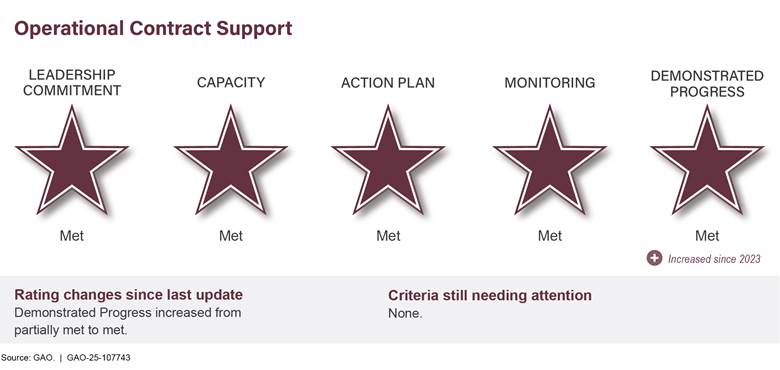

DOD issued department-wide and combatant command-specific guidance for operational contract support and embedded it into training and planning. Operational contract support includes supplies, services, and construction for deployed military forces around the world. Because of these actions, DOD has achieved a met rating in all five criteria for the operational contract support segment of this high-risk area. That segment is being removed from the area.

To address challenges with service acquisitions, DOD created an action plan with steps to more strategically manage services. Service acquisitions include management, IT, and administrative support. DOD also developed a dashboard to monitor spending on these acquisitions. To make further progress, DOD should ensure military department guidance identifies responsibilities to collectively prioritize, aggregate, and review service requirements on a recurring basis and finalize the methodology for forecasting budget needs.

|

|

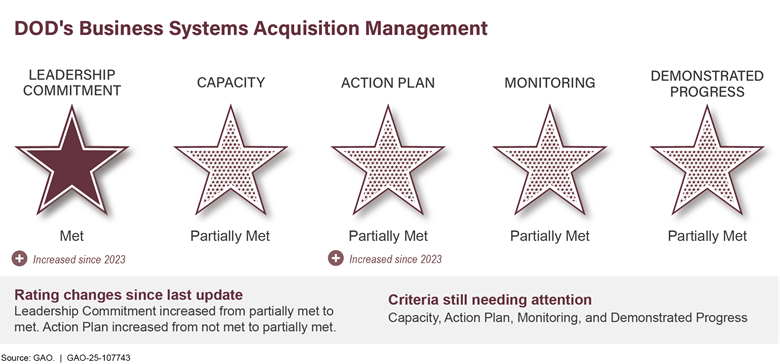

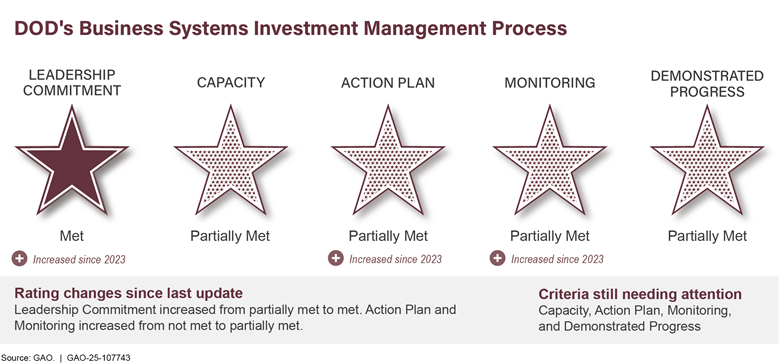

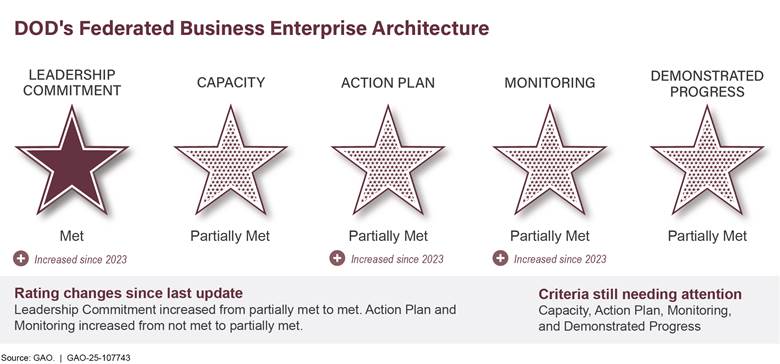

The rating for the leadership commitment criterion increased to met due, in part, to the Secretary of Defense issuing a department-wide memorandum calling for DOD to take steps to remove DOD business systems modernization from the High-Risk List. The memorandum also called for the department CIO to accelerate the retirement of noncompliant legacy defense business systems. Additionally, DOD developed a draft action plan that includes specific actions and associated milestones to better manage business systems acquisitions, investment management, and business enterprise architecture efforts.

To make further progress, DOD needs to improve management of its business systems acquisitions by enhancing its investment management guidance and completing planned updates to its federated business enterprise architecture.

|

|

National Efforts to Prevent, Respond to, and Recover from Drug Misuse |

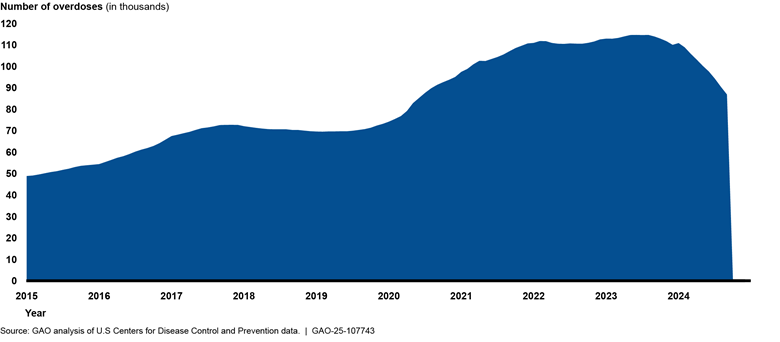

Federal agencies have increased their capacity to reduce drug overdose deaths, such as by expanding access to opioid overdose reversal medication. As of February 2025, estimates by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the 12-month period ending in September 2024 were part of the first substantial drop in predicted provisional overdose deaths since January 2015. However, agencies still need to determine the cause of this decline, and the number of overdose deaths remains high.

To make further progress, federal agencies must effectively coordinate and implement a strategic national response and make progress toward reducing drug misuse rates, overdose deaths, and the resulting harmful effects to society.

The additional five high-risk areas that made progress since 2023 are Resolving the Federal Role in Housing Finance, USPS Financial Viability, Emergency Loans for Small Businesses, Government-wide Personnel Security Clearance Process, and U.S. Government’s Environmental Liability. Additional details on these areas can be found in app. III.

High-Risk Areas Have Made Varied Progress

Twenty-two high-risk areas have met one or more of the five criteria for removal from the High-Risk List. Ten areas improved while three areas declined since our last update in 2023 (see table 3).[7] Most areas, while making some improvements, maintained their prior ratings.

|

High-risk area |

Change since 2023 list |

Number of criteria |

||

|

|

|

Met |

Partially met |

Not met |

|

National Flood Insurance Programa |

↑ |

5 |

0 |

0 |

|

DOD Approach to Business Transformation |

↑ |

3 |

2 |

0 |

|

DOD Contract Management |

↑ |

3 |

2 |

0 |

|

Resolving the Federal Role in Housing Financea,b |

↑ |

3 |

2 |

0 |

|

USPS Financial Viabilitya |

↑ |

3 |

2 |

0 |

|

Emergency Loans for Small Businesses |

↑ |

2 |

3 |

0 |

|

Government-wide Personnel Security Clearance Processa,b |

↑ |

2 |

3 |

0 |

|

DOD Business Systems Modernization |

↑ |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

National Efforts to Prevent, Respond to, and Recover

from |

↑ |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

U.S. Government’s Environmental Liabilitya,b |

↑ |

0 |

3 |

2 |

|

Managing Federal Real Propertyb |

↓ |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

DOD Weapon Systems Acquisitiona |

↓ |

0 |

4 |

1 |

|

Improving IT Acquisitions and Managementa,b |

↓ |

0 |

3 |

2 |

|

NASA Acquisition Management |

• |

4 |

1 |

0 |

|

Strengthening Department of Homeland Security IT and |

• |

3 |

2 |

0 |

|

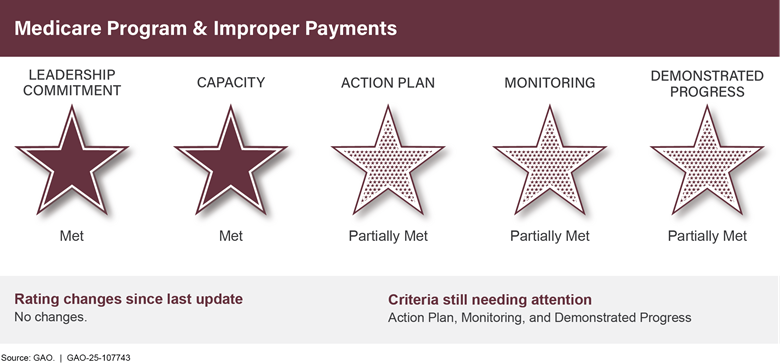

Medicare Program & Improper Paymentsa |

• |

2 |

3 |

0 |

|

Acquisition and Program Management for DOE’s National |

• |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

DOD Financial Management |

• |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

Enforcement of Tax Lawsa |

• |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

Ensuring the Cybersecurity of the Nationa,b |

• |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

Improving Federal Management of Programs That Serve |

• |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

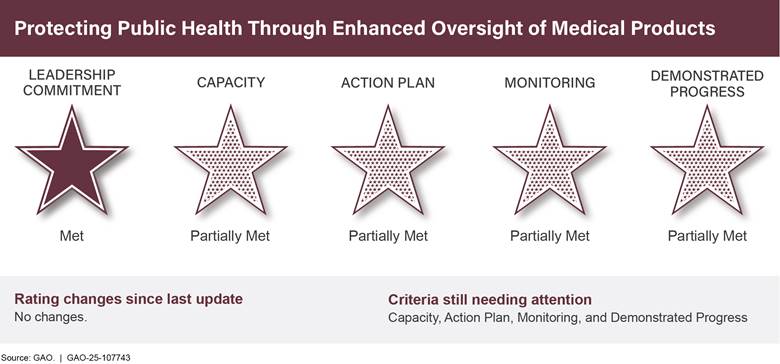

Protecting Public Health Through Enhanced Oversight

of |

• |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

Protecting Technologies Critical to U.S. National Securityb |

• |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

VA Acquisition Management |

• |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

Strategic Human Capital Managementb |

• |

1 |

3 |

1 |

|

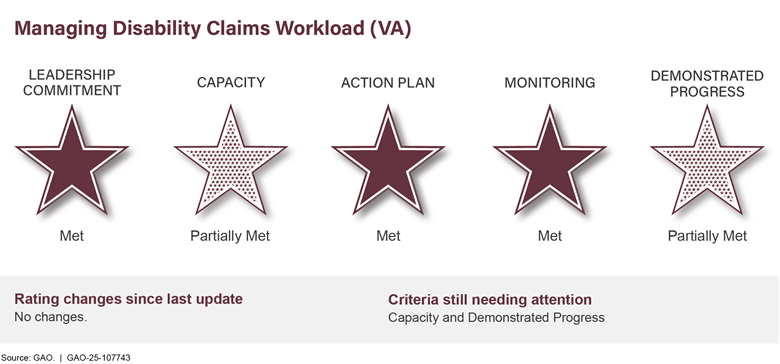

Improving and Modernizing Federal Disability Programsb |

• |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

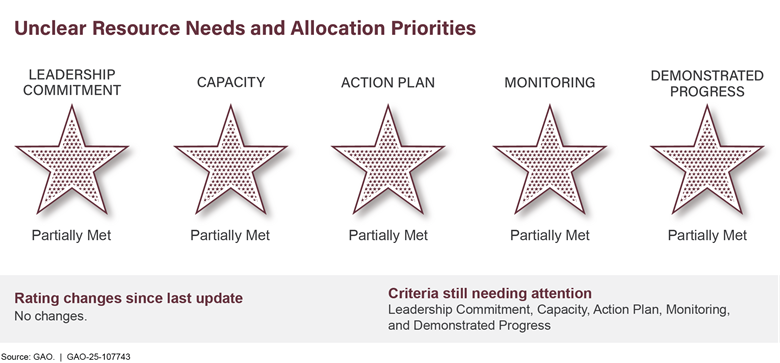

Management of Federal Oil and Gas Resources |

• |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

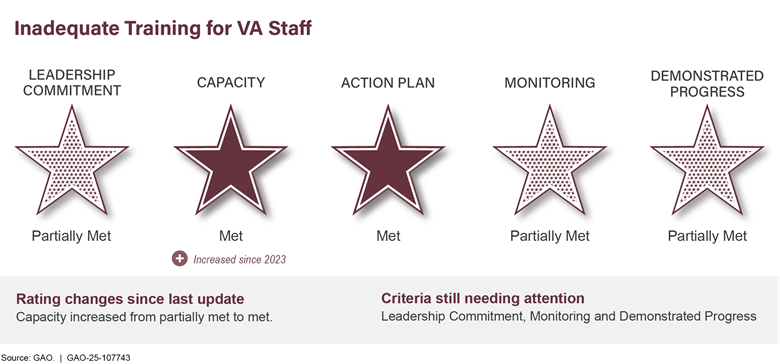

Managing Risks and Improving VA Health Care |

• |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

Modernizing the U.S. Financial Regulatory Systema,b |

• |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

Strengthening Medicaid Program Integritya,b |

• |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

Transforming EPA’s Process for Assessing and Managing

|

• |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

Limiting the Federal Government’s Fiscal Exposure by

Better |

• |

0 |

4 |

1 |

|

Improving Federal Oversight of Food Safetya,b |

• |

0 |

3 |

2 |

|

Unemployment Insurance Systema,b (area rated for the first time) |

n/a |

2 |

3 |

0 |

|

Strengthening Management of the Federal Prison System |

n/a |

0 |

5 |

0 |

|

HHS Leadership and Coordination of Public Health

Emergenciesb |

n/a |

0 |

2 |

3 |

|

Funding the Nation’s Surface Transportation Systema |

n/a |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistancea,b |

n/a |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Legend:

↑: area progressed on one or more criteria since 2023

↓: area declined on one or more criteria since 2023

●: no change in rating since 2023

n/a: not applicable

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107743

aLegislation is likely to be necessary to effectively address this high-risk area.

bCoordinated efforts across multiple entities are necessary to effectively address this high-risk area.

Figure 11 and table 4 summarize the status for high-risk areas that remain on the List and rating changes since the last update.

Figure 11: Number of 2025 High-Risk Areas Receiving Met, Partially Met, and Not Met Ratings for Each Criterion and Area Ratings Changes Since 2023

Note: The figure reflects ratings of overall high-risk areas. It does not include two areas that did not receive ratings in this update.

Table 4: 2025 High-Risk Area Ratings and Rating Changes on Five Criteria for Removal from GAO’s High-Risk List

|

|

Criteria |

||||

|

High-risk area |

Leadership commitment |

Capacity |

Action plan |

Monitoring |

Demonstrated progress |

|

National Flood Insurance Program |

|

|

|

|

|

|

NASA Acquisition Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

DOD Approach to Business Transformation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

DOD Contract Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resolving the Federal Role in Housing Finance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Strengthening Department of Homeland Security IT and Financial Management Functions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

USPS Financial Viability |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emergency Loans for Small Businesses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Medicare Program & Improper Payments |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Government-wide Personnel Security Clearance Process |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unemployment Insurance System |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Acquisition and Program Management for DOE’s National Nuclear Security Administration and Office of Environmental Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

DOD Business Systems Modernization |

|

|

|

|

|

|

DOD Financial Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enforcement of Tax Laws |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ensuring the Cybersecurity of the Nation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Improving Federal Management of Programs that Serve Tribes and Their Members |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Managing Federal Real Property |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Protecting Public Health Through Enhanced Oversight of Medical Products |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Protecting Technologies Critical to U.S. National Security |

|

|

|

|

|

|

VA Acquisition Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Strategic Human Capital Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Improving and Modernizing Federal Disability Programs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Management of Federal Oil and Gas Resources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Managing Risks and Improving VA Health Care |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Modernizing the U.S. Financial Regulatory System |

|

|

|

|

|

|

National Efforts to Prevent, Respond to, and Recover from Drug Misuse |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Strengthening Management of the Federal Prison System |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Strengthening Medicaid Program Integrity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Transforming EPA’s Process for Assessing and Managing Chemical Risks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

DOD Weapon Systems Acquisition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Limiting the Federal Government’s Fiscal Exposure by Better Managing Climate Change Risks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Improving Federal Oversight of Food Safety |

|

|

|

|

|

|

U.S. Government's Environmental Liability |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Improving IT Acquisitions and Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

HHS Leadership and Coordination of Public Health Emergencies |

|

|

|

|

|

Legend:

![]() Met

Met ![]() Partially Met

Partially Met ![]() Not Met

Not Met ![]() Increased

Increased ![]() Decreased

Decreased

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107743

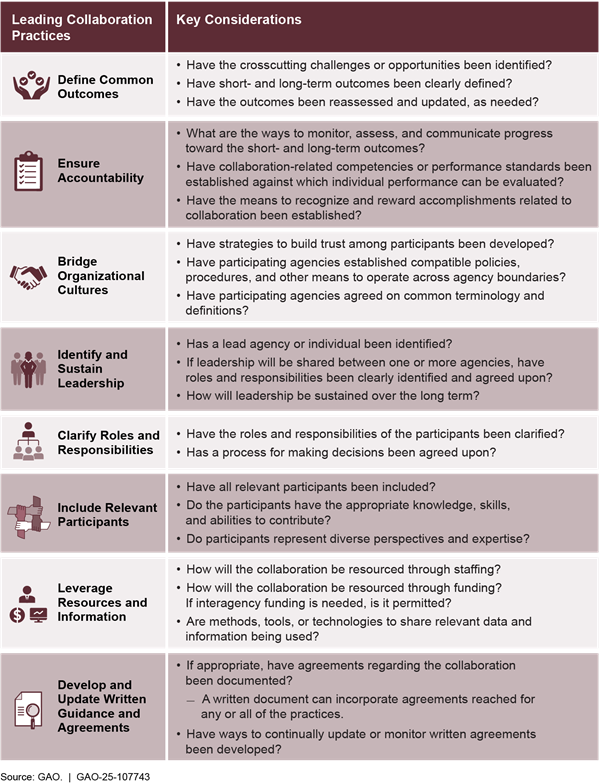

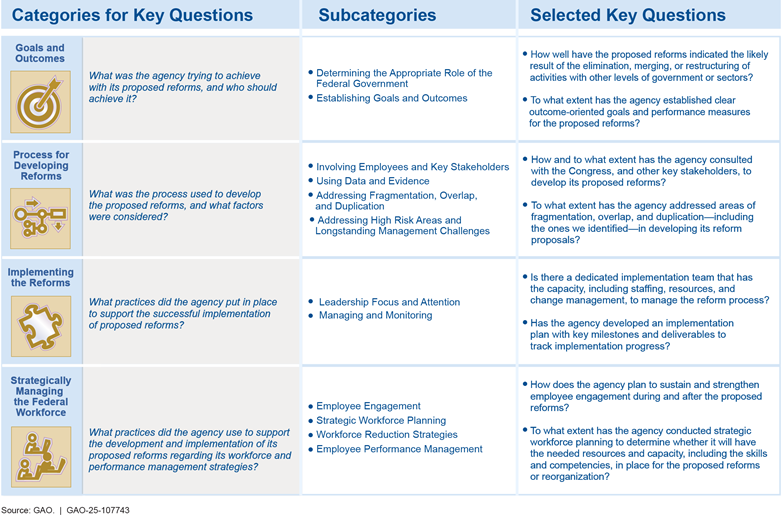

Effective Interagency Collaboration Is Essential to Making Progress on High-Risk Areas

High-risk areas are among the most technically complex and challenging issues for government to address. Achieving meaningful progress on high-risk areas requires coordinated efforts across federal agencies, often with other governments (for example, at state and local levels), nongovernmental organizations, contractors, and the private sector. At least 18 areas on the current High-Risk List involve coordinated efforts across agencies and other entities.

There are several tools for forging successful partnerships across groups. One way progress has been made on high-risk areas is through interagency working groups and other mechanisms that bring together the relevant federal agencies and entities. We have developed eight leading practices for agencies to effectively work together on shared goals (see fig. 12).[8]

However, a lack of or ineffective collaboration can stall progress. When interagency groups do not collaborate effectively, they can struggle to address government-wide challenges on high-risk areas. For example:

· The Food Safety Working Group, composed of officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, FDA, and Food Safety and Inspection Service, and established in 2009 to coordinate federal efforts and develop goals to make food safer, has not met since 2011 and is no longer active.

· The disparate and fragmented delivery of federal disaster recovery efforts makes it difficult for communities to know who to turn to for help.

Congress will increasingly need to provide oversight of integrated approaches to help its decision-making on the many issues requiring effective collaboration across federal agencies, levels of government, and sectors. Congress should consider requiring that interagency groups formed to address these challenges develop and implement a collaboration plan incorporating the leading interagency collaboration practices. This would help the groups increase their efficiency and effectiveness and achieve intended outcomes.

Matter for Congressional Consideration

Congress should consider requiring that interagency groups formed to address high-risk and other key challenges develop and implement a collaboration plan incorporating GAO’s leading interagency collaboration practices. (Matter for Congressional Consideration 1)

The high-risk program continues to be a top priority at GAO. We will maintain our emphasis on identifying high-risk issues across government and on providing recommendations and sustained attention to help address them. We will also continue working collaboratively with Congress, agency leaders, and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to address these issues.

OMB’s role is especially important because many high-risk areas are government-wide or involve multiple agencies. Resource investments are also associated with correcting a number of high-risk problems. OMB is required to conduct portfolio reviews to address programs identified by GAO as high risk.[9] OMB has worked to develop a standardized, federal government-wide approach to building agencies’ capacity for improved program and project management, including reviewing portfolios of agency programs, assessing their effectiveness, and offering guidance to agencies for improved program management. These actions could enhance progress on high-risk areas.

Progress has been achieved through leadership meetings between OMB, agencies, and GAO to discuss planned actions to address individual high-risk areas. OMB accelerated the pace of these meetings in the past 4 years. Since the beginning of this 4-year cycle of trilateral meetings in 2021, OMB has convened meetings on 23 high-risk areas. These trilateral meetings led to greater progress on high-risk issues. We expect OMB to continue to hold these meetings with a goal of meeting on all high-risk areas before our next update in 2027.

We are providing this update to the President and Vice President, congressional leadership, the appropriate congressional committees, other Members of Congress, OMB, and the heads of major departments and agencies.

Gene L. Dodaro

Comptroller General

of the United States

We developed guidance to determine which federal programs and functions should be designated high risk.[10] We consider qualitative factors, such as whether the risk

· involves public health or safety, service delivery, national security, national defense, economic growth, or privacy or citizens’ rights; or

· could result in significantly impaired service, program failure, injury, or loss of life, or significantly reduce economy, efficiency, or effectiveness.

We also consider the exposure to loss in monetary or other quantitative terms. At a minimum, $1 billion must be at risk in areas such as

· the value of major assets being impaired;

· revenue sources not being realized;

· major agency assets being lost, stolen, damaged, wasted, or underused;

· potential for, or evidence of, improper payments or fraud; or

· presence of contingencies or potential liabilities.

Before designating an area as high risk, we also consider the status and effectiveness of corrective measures that are planned or under way.

To make progress on high-risk areas, administration and agency leaders need to provide top-level attention. Congressional action is also needed for some high-risk areas. We determine whether to remove agencies from the High-Risk List based on whether their actions are grounded in the five criteria for removal below (see fig. 13).

We rate high-risk areas on the following scale:

Met. Actions have been taken that meet the criterion. There are no significant actions that need to be taken to further address this criterion.

Partially met. Some, but not all, actions necessary to meet the criterion have been meet.

Not met. Few, if any, actions toward meeting the criterion have been taken.

Figure 14 illustrates the varying degrees of progress in each of the five criteria for a high-risk area.

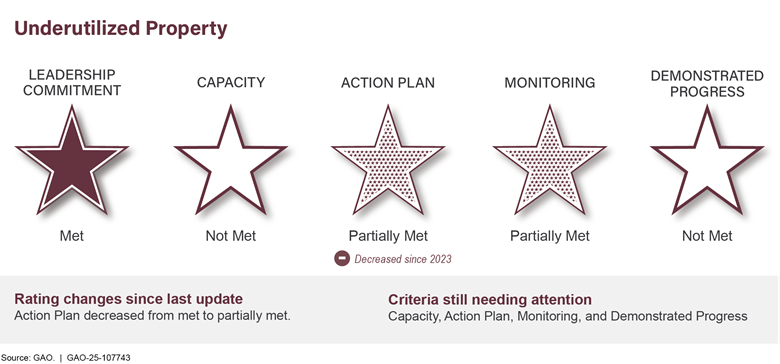

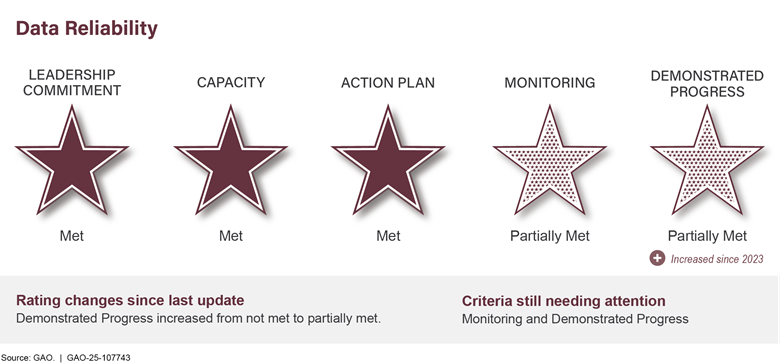

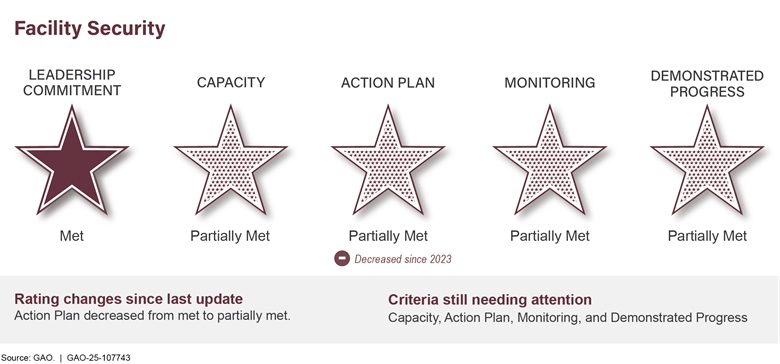

Some high-risk areas are divided into segments. For example, the high-risk area Managing Federal Real Property includes four segments—Underutilized Property, Data Reliability, Facility Security, and Building Condition—to reflect four interrelated parts of the overall high-risk area. Multidimensional high-risk areas such as these have separate ratings for each segment as well as a summary rating that reflects a composite of the ratings. We do not rate high-risk areas that primarily need congressional action.

In 1990, we began a program to report on government operations that we identified as high risk. Since then, generally coinciding with the start of each new Congress, we have reported on the status of progress addressing high-risk areas and have updated the High-Risk List. Our last high‑risk update was in April 2023.[11] That update identified 37 high-risk areas. This year, we added one high-risk area—Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistance. With this addition, this 2025 update identifies 38 high-risk areas.

Overall, this program has served to identify and help resolve serious weaknesses in areas that involve substantial resources and provide critical services to the public. Since our program began, the federal government has taken high-risk problems seriously and has made long-needed progress toward correcting them. In 29 cases, progress has been sufficient for us to remove the high-risk designation. A summary of changes to our High-Risk List over the past 35 years is shown in table 5.

|

|

Number of areas |

|

Original High-Risk List in 1990 |

14 |

|

High-risk areas added since 1990 |

54a |

|

High-risk areas removed since 1990 |

29 |

|

High-risk areas separated out from existing area |

2 |

|

High-risk areas consolidated since 1990 |

2 |

|

High-Risk List in 2025 |

38 |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107743

aThis number includes areas that are also counted as “High-risk areas separated out from existing area.”

How Can Agencies Use the Criteria to Make Progress on High-Risk Issues?

The five high-risk criteria form a roadmap for efforts to improve and ultimately address high-risk issues. Addressing some of the criteria leads to progress, while satisfying all criteria is central to removal from the list. Congressional attention, Office of Management and Budget engagement, and federal agencies’ sustained leadership, planning, and execution are key practices for successfully addressing high-risk areas.

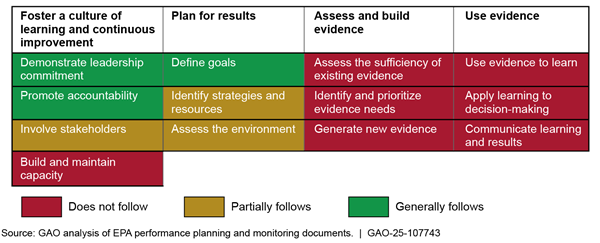

In March 2022, we reported on key practices for addressing the five high-risk criteria to facilitate progress on high-risk areas. See figure 15 for key practices that can help agencies demonstrate leadership commitment and sustain continuity for high-risk efforts.

What Is the History of Programs Removed from the High-Risk List?

A summary of areas removed from our High-Risk List over the past 35 years is shown in table 6.

|

High-risk area |

Year removed |

Years on list |

|

Federal Transit Administration Grant Management |

1995 |

5 |

|

Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation |

1995 |

5 |

|

Resolution Trust Corporation |

1995 |

5 |

|

State Department Management of Overseas Real Property |

1995 |

5 |

|

Bank Insurance Fund |

1995 |

4 |

|

Customs Service Financial Management |

1999 |

8 |

|

Farm Loan Programs |

2001 |

11 |

|

Superfund Programs |

2001 |

11 |

|

National Weather Service Modernization |

2001 |

6 |

|

The 2000 Census |

2001 |

4 |

|

The Year 2000 Computing Challenge |

2001 |

4 |

|

Asset Forfeiture Programs |

2003 |

13 |

|

Supplemental Security Income |

2003 |

6 |

|

Student Financial Aid Programs |

2005 |

15 |

|

FAA Financial Management |

2005 |

6 |

|

Forest Service Financial Management |

2005 |

6 |

|

HUD Single-Family Mortgage Insurance & Rental Housing Assistance Programs |

2007 |

13 |

|

U.S. Postal Service’s Transformation Efforts and Long-term Outlook |

2007 |

6 |

|

FAA’s Air Traffic Control Modernization |

2009 |

14 |

|

DOD Personnel Security Clearance Program |

2011 |

6 |

|

2010 Census |

2011 |

3 |

|

IRS Business Systems Modernization |

2013 |

18 |

|

Management of Interagency Contracting |

2013 |

8 |

|

Establishing Effective Mechanisms for Sharing and Managing Terrorism-Related Information to Protect the Homeland |

2017 |

12 |

|

DOD Supply Chain Management |

2019 |

29 |

|

Mitigating Gaps in Weather Satellite Data |

2019 |

6 |

|

DOD Support Infrastructure Management |

2021 |

24 |

|

2020 Decennial Census |

2023 |

6 |

|

Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation Insurance Programs |

2023 |

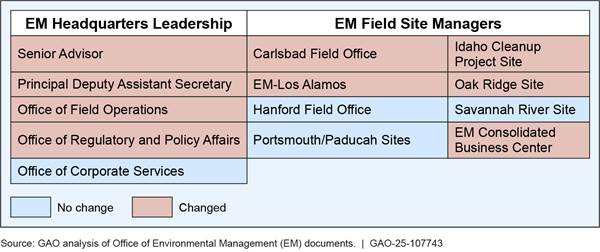

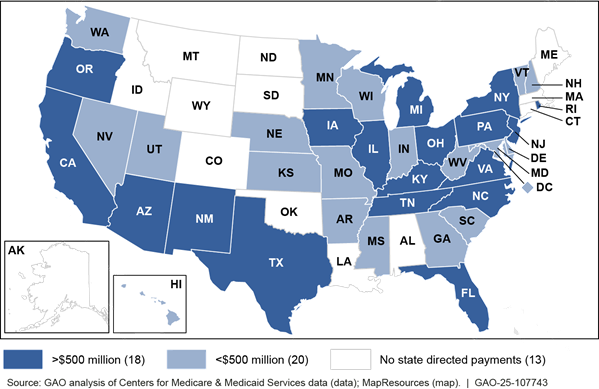

20 |